Background

Ascariasis is a prevalent helminthic infection primarily caused by the parasitic worm Ascaris lumbricoides, with a less common occurrence of Ascaris suum, which is associated with pigs. [1, 2, 3, 4] As of 2013, there were an estimated 804 million cases worldwide, making it the most common helminthic infection. While many light infections are asymptomatic, early symptoms can include pulmonary issues such as cough and wheezing. As the infection progresses, gastrointestinal complications may arise, including cramps and abdominal pain due to blockages caused by adult worms in the intestines or biliary and pancreatic ducts. Chronic infections, especially in children, can lead to undernutrition and growth retardation.

Ascariasis is most prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions with poor sanitation, particularly affecting children aged 2 to 10 years. It is estimated that around 500 million people are infected globally, with the disease contributing to malnutrition and causing approximately 2,000 to 10,000 deaths annually, primarily due to bowel or biliary tract obstruction in children. In the United States, most cases occur among refugees, immigrants, or travelers returning from endemic areas.

Humans become infected with A. lumbricoides by ingesting its eggs, often through food contaminated with human feces or by putting contaminated hands or fingers in their mouths. Additionally, humans can contract A. suum from pigs by handling them or consuming undercooked vegetables or fruits contaminated with pig feces. The classification of A. suum as a distinct species from A. lumbricoides remains a subject of debate.

Diagnosis typically is made by identifying eggs or adult worms in stool samples, observing adult worms that migrate from the nose or mouth, or, in rare cases, detecting larvae in sputum during the pulmonary migration phase. Treatment options include albendazole, mebendazole, or ivermectin. Ascariasis is most prevalent in children in tropical and developing countries,{4 where it is perpetuated by soil contamination with human feces or the use of untreated feces as fertilizer. [5] While Ascariasis suum also can cause infections, it is primarily transmitted from person to person in most endemic areas. [6, 7] A suum is very similar to Ascaris lumbricoides, [8, 9] but, in most endemic areas, it most likely is transmitted from person to person. [10]

Symptomatic ascariasis may manifest during the adult worm's intestinal or larval migration phase, leading to complications such as pneumonitis, intestinal obstruction, or hepatobiliary and pancreatic injury.

For more information on ascariasis in children, see the Medscape article Pediatric Ascariasis.

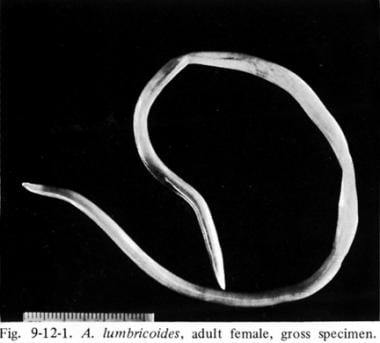

The image below depicts a roundworm that infects humans through soil contaminated by human feces.

See Common Intestinal Parasites, a Critical Images slideshow, to help make an accurate diagnosis.

Pathophysiology

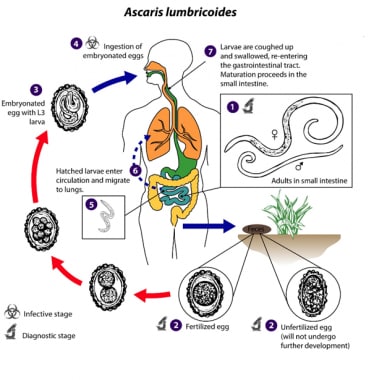

When ingested, Ascaris lumbricoides eggs hatch in the duodenum, and the larvae penetrate the small bowel wall, migrating through the portal circulation to the liver, heart, and lungs. Once in the lungs, the larvae lodge in the alveolar capillaries, penetrate the alveolar walls, and ascend the bronchial tree to the oropharynx. They then are swallowed and return to the small intestine, where they mature into adult worms that mate and release eggs into the stool. This life cycle takes about 2 to 3 months, with adult worms living for 1 to 2 years.

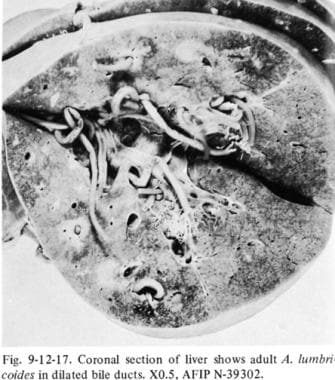

Heavy infections can lead to a tangled mass of worms that obstructs the bowel, particularly in children. [4] Occasionally, individual adult worms may migrate aberrantly and obstruct the biliary or pancreatic ducts, resulting in conditions such as cholecystitis or pancreatitis, while cholangitis, liver abscess, and peritonitis are less common. Fever from other illnesses or certain medications, such as albendazole or mebendazole, may trigger this aberrant migration. A lumbricoides is the largest common nematode infecting humans, with adult worms measuring 15 to 35 cm in length and living in the jejunum and middle ileum of the intestine for 10 to 24 months.11 Female A lumbricoides can produce up to 240,000 eggs daily, which are fertilized by nearby males. The eggs are oval, measuring 45-70 x 35-50 microns, and have a thick outer shell.

Research indicates that 45% of infected individuals shed only fertilized eggs, 40% shed both fertilized and unfertilized eggs, and 20% shed only unfertilized eggs, with unfertilized eggs accounting for only 6-9% of total egg shedding. Fertilized eggs can become infectious within 5-10 days when released into suitable soil and can remain viable for up to 10 years. Infection occurs through the oral ingestion of food or water contaminated with soil containing embryonated eggs from human or pig feces, or by directly consuming infected uncooked pig or chicken liver containing larvae. While eggs can survive in chemically treated water, they can be eliminated by boiling or filtering water sources. [11, 12]

Life cycle of Ascaris lumbricoides. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html].

Life cycle of Ascaris lumbricoides. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html].

Adult worms (females 20 to 35 cm; males 15 to 30 cm) (1) live in the lumen of the small intestine. A female may produce approximately 200,000 eggs per day, which are passed with the feces (2) . Unfertilized eggs may be ingested but are not infective. Fertile eggs embryonate and become infective after 18 days to several weeks (3) , depending on the environmental conditions (optimum: moist, warm, shaded soil). After infective eggs are swallowed (4) , the larvae hatch out of eggs (5) , invade the intestinal mucosa, and are carried via the portal, then systemic circulation to the lungs (6) . The larvae mature further in the lungs (10-14 days), penetrate the alveolar walls, ascend the bronchial tree to the throat, and are swallowed (7) . Upon reaching the small intestine, they develop into adult worms (1) . Between 2 and 3 months are required from ingestion of the infective eggs to oviposition by the adult female. Adult worms can live 1 to 2 years. [13]

Larva of A lumbricoides hatching from an egg. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html].

Larva of A lumbricoides hatching from an egg. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html].

[13] Reproduced from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx: Ascariasis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html.

Larvae are released from the Ascaris eggs in the small intestine within 4 days of ingestion. These larvae migrate through cecum and proximal colon and penetrate the intestinal mucosa and reach the liver via the portal circulation. They enter the heart through the hepatic veins, infiltrate the lymphatics and end up in the lungs where they mature in about 2 weeks. The mature larvae cause symptoms of pneumonitis and ascend the trachea by the cough reflex. They are swallowed by the host to mature into adult worms in the intestinal tract where each female worm lays over 200,000 eggs daily within 1 to 11 weeks of infection. [14] Eggs are infective only if both male and female worms are present. Although the majority of worms are found in the lumen of the jejunum, they may be seen in any part of the intestine as well as ectopic sites such as the kidneys or brain. Adult worms can live up to 2 years and are passed in the stool. The worm burden increases with reinfections in endemic areas and can be as high as 200 worms per individual. [15]

A significant exposure may produce subsequent pneumonia and eosinophilia. Symptoms of pneumonitis include wheezing, dyspnea, nonproductive cough, hemoptysis, and fever. Larvae are expectorated and swallowed, eventually reaching the jejunum, where they mature into adults in approximately 65 days. Adult worms feed on digestion products of the host. Children with a marginal diet may be susceptible to protein, caloric, or vitamin A deficiency, resulting in retarded growth and increased susceptibility to infectious diseases such as malaria. [16] Large and tangled worms may cause intestinal (usually ileal), common duct, pancreatic, or appendiceal obstruction. Mean worm burden varies from more than 16 to 4 and appears related to host factors, particularly age, geophagy, [17] and immunity. Worms do not multiply in the host. For infection to persist beyond the 2-year maximum lifespan of the worms, re-exposure must occur. Some children appear to become very heavily infested, probably from multiple cumulative exposures over time and/or relative immunodeficiency. [18]

Ascaris lumbricoides suum, a swine nematode, is thought responsible for zoonotic infection. Distinguishing this worm from A lumbricoides is difficult, as it differs by only 6 (1.3%) nucleotides in the first internal transcribed spacer (ITS-1) and by 3%-4% in the mitochondrial genome sequence. [18] A suum appears to responsible for most ascariasis cases in well-developed countries with excellent sanitation (eg, Denmark, [19] United States, [9] UK [20] ). In this setting, infected persons have a low worm burden and may present with only cough, acute eosinophilia, or eosinophilic liver lesions visible on CT scans. However, a molecular genetic study from China casts doubt that infections in pigs are the cause of most human infection. [10]

Ascariasis is transmitted mainly by ingestion of food or water that has been contaminated by the fertilized infected eggs of A. lumbricoides or A. suum. Poor hand hygiene, polluted water and unsanitary food preparation play major role in reinfections in endemic areas and lingers in families and group homes with shedding of eggs by asymptomatic individuals. No immunity develops with past infections or treatment and other parasitic infections may coexist. A. suum infection is common in pig farmers and eating uncooked meat or vegetables grown in soil fertilized by pig manure. [21, 22]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

In 1974, an estimated 4 million people, mainly in the southeast United States, had ascariasis. Recent estimates of ascariasis prevalence are much lower. Immigrants from countries with a high prevalence of ascariasis comprise most recent cases. In the past, it was most prevalent in the southeast United States, but after introduction of modern waste management systems and sanitation, the numbers have sharply declined. [23]

International

The prevalence of ascariasis is highest in children aged 2 to 10 years, with the highest intensity of infection occurring in children aged 5 to 15 years who have simultaneous infections with other soil-transmitted helminths, such as Trichuris trichiura and hookworm. The warm, wet climate of tropical countries with suboptimal sanitation is a very favorable environment for the transmission of helminth infections. The prevalence decreases after the age of 15 years. A Vietnamese study found that adult women living in rural areas, especially those exposed to human night soil and living in households without a latrine, were at surprisingly high risk for ascariasis. [24] In regions with soil-transmitted diseases, ascariasis tends to be more geographically dispersed than Trichuris or hookworm. [25]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that that there are more than one billion cases of A. lumbricoides infection worldwide. [26, 27] Ascariasis rates in 2005 were as follows: 86 million cases in China, 204 million elsewhere in East Asia and the Pacific, 173 million in sub-Saharan Africa, 140 million in India, 97 million elsewhere in South Asia, 84 million in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 23 million in the Middle East and North Africa. Between 1990 and 2013, the disease burden of ascariasis was estimated to have decreased by 75%. [2] Survey data, however, are corrupted by lack of standardized diagnostic methods. [28]

Because the lifespan of adult worms in the intestine is only 1 to 2 years, persistent infection requires frequent re-exposure and reinfection. The frequency and intensity of infection remain high throughout life in endemic areas and pose a risk to both elderly and young persons. In a recent study in rural southwest Nigeria, the intensity of excreted eggs per gram of feces among infected persons was 2371 for Ascaris species, 1070 for hookworm, and 500 for Trichuris species, with only slightly lower rates among persons in urban areas. [29]

Estimates of disability-adjusted years of life due to ascariasis have fallen because of development and management programs during the 1990s, especially in Asia, but still constitute a significant burden in some countries. Current ascariasis-associated disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are approximately 1 million, [2] with nonsurgical morbidity mostly associated with wasting syndrome in children. [2]

A suum infections have been seen in countries where pigs are raised and pig manure is used as a fertilizer. [11, 30] These have been reported in China, [31] Japan, [30] Thailand, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Myanmar, [32] the United States, [33] and Europe. [8, 19]

Mortality/Morbidity

Most A lumbricoides or A suum infections are asymptomatic especially in adults. Severe, symptomatic ascariasis is most common in children. Intestinal obstruction caused by heavy worm burden (≥60) is the most common presenting manifestation of disease. An estimated 2 per 1000 infected children develop intestinal obstruction per year. [34] Among children aged 1 to 12 years who presented to a Cape Town hospital with abdominal emergencies between 1958-1962, symptomatic A lumbricoides infection was responsible for 12.8% of cases, with 68% of those due to intestinal obstruction, usually at the terminal ileum. The peak incidence was at age 2 years in a series from Colombia and age 4.8 years in a series from Turkey.

The prevalence of infection in Vietnam is estimated at 44.4%, more commonly in the northern peri-urban and rural areas of the country. [35] In Vietnam, vegetable cultivation using night soil fertilizer places adult women at especially high risk. Children with chronic ascariasis may experience decreased growth and development due to decreased food intake.

The disease is commonly symptomatic during the early phase larval migration stage with pulmonary symptoms and in late-phase adult worm intestinal stage and manifests as intestinal, hepatobiliary, or pancreatic symptoms. Within weeks of new infection, pulmonary manifestations may be seen but are uncommon in patients from endemic areas or reinfections. This was demonstrated by a study of 13,00 patients in and endemic region of Columbia with only 4 cases of Loeffler syndrome. [36, 37, 38]

Adults with ascariasis are more likely to develop biliary complications due to migration of adult worms, possibly provoked by other illnesses such as malarial fever. In Damascus, of 300 adults referred for complications of ascariasis between 1988 and 1993, 98% had abdominal pain, 4.3% had acute pancreatitis, 1.3% had obstructive jaundice, and 25% had worm emesis. Twenty-one to 80% of patients had undergone previous cholecystectomy or endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Because of improved access to care and availability of ultrasonography, biliary ascariasis has been increasingly recognized and reported from endemic areas. [39] In Kashmir, it may account for up to 36% of patients presenting with biliary or pancreatic disorders and is reported to cause 20% of biliary disease in the Philippines. [39] A review of biliary ascariasis suggests that this association may be causative as a result of dilatation of the common bile duct and elevation of cholecystokinin levels with resultant relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi. [40]

A report from India indicated that, of consecutive patients diagnosed with biliary ascariasis, 80% presented with recurrent abdominal pain, 30% with acute cholecystitis, 25% with obstructive jaundice, 25% with cholangitis, only 5% with pancreatitis, 5% with perforated viscus, and 5% with hepatolithiasis. Only 25% of the Indian patients required surgery, and conservative medical therapy with oral anthelminthics has recently been recommended. [39]

A postcholecystectomy syndrome of pain and jaundice is frequently due to ascariasis in endemic areas, presumably owing to enhanced patency of the biliary system after surgical or endoscopic sphincterotomy. [41]

Intestinal obstruction, usually of the terminal ileum in children, is the most commonly attributed fatal complication, resulting in 60,000 deaths per year. [3] Besides direct obstruction of the bowel lumen, toxins released by live or degenerating worms may result in bowel inflammation, ischemia, and fibrosis.

Age

See International and Mortality/Morbidity.

Prognosis

Universal treatment is effective in endemic areas regardless of asymptomatic infections. However in non-endemic areas, screening or empiric treatment is based on the high pretest probability, especially in patients with history of travel to endemic areas or exposure to infected populations. Immediate cure rates after single-dose albendazole in South Africa were 95%, with egg reduction rates of more than 99%. [42]

Most treated patients become reinfected within months unless they are relocated to an area of significantly improved sanitation.

Patient Education

Because of the limited (2-year) lifespan of the disease, education on hand hygiene, fecal waste disposal, and general public health could be instrumental in breaking the cycle of infection in households and communities. [3]

-

Adult Ascaris lumbricoides.

-

Life cycle of Ascaris lumbricoides.

-

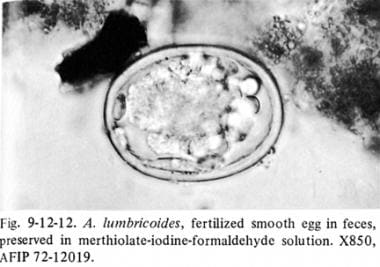

Ascaris lumbricoides egg.

-

Adult Ascaris lumbricoides in biliary system.

-

Life cycle of Ascaris lumbricoides. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html].

-

Larva of A lumbricoides hatching from an egg. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ascariasis/index.html].