Practice Essentials

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), a spondyloarthropathy, is a chronic, multisystem inflammatory disorder involving primarily the sacroiliac (SI) joints and the axial skeleton. Chronic back pain and spinal stiffness are the most common presenting features, but peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis, as well as extra-musculoskeletal manifestations such as acute anterior uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis also occur frequently. [1] See the image below.

Because sacroiliitis on radiography is a major criterion for AS, and MRI studies have shown that the disease starts long before definite changes in the SI joints become visible on radiographs, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) recommends axial spondyloarthritis as the overall term for the disease. Axial spondyloarthropathy is divided into radiographic axial sponyloarthropathy (r-axSpA) and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy (nr-axSpA). The term r-axSpA is interchangeable with (but preferred to) AS, while the term nr-axSpA applies to patients with predominantly axial features and includes patients with clinical features of AS but with normal plain radiographs of the SI joints and spine. [2] Nr-axSpA probably represents an earlier phase or milder form of AS.

Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy (USpA) is used to describe patients with predominantly peripheral features. USpA may represent an early phase or incomplete form of AS or another spondyloarthropathy such as psoriatic arthritis.

The outcome in patients with axial spondyloarthritis, including AS, is generally good compared with that in patients with a disease such as rheumatoid arthritis. Nevertheless, AS is a chronic progressive disease that can result in significant morbidity.

Signs and symptoms

Ankylosing spondylitis

Key components of the patient history that suggest AS include back pain with the following features [3] :

-

Improvement of symptoms with exercise [4]

-

Pain at night

-

Insidious onset of low back pain (symptoms for at least 3 months) - The most common symptom

-

Onset of symptoms before age 40 years

-

No improvement with rest

General symptoms of AS include the following:

-

Those related to inflammatory back pain - Stiffness of the spine and kyphosis resulting in a stooped posture are characteristic of advanced-stage AS.

-

Peripheral enthesitis and arthritis

-

Constitutional and organ-specific extra-articular manifestations

Fatigue is another common complaint, occurring in approximately 45% of patients with AS. Increased levels of fatigue are associated with increased pain and stiffness and decreased functional capacity. [5]

Extra-articular manifestations of AS can include the following:

-

Uveitis

-

Cardiovascular disease

-

Pulmonary disease

-

Kidney disease

-

Neurologic disease

-

Gastrointestinal (GI) disease

-

Metabolic bone disease

Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy

Clinical manifestations of undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy include the following:

-

Inflammatory back pain - 90%

-

Buttock pain - 80%

-

Enthesitis - 85%

-

Peripheral arthritis - 35%

-

Dactylitis - 17%

-

Fatigue - 55%

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of AS is generally made by combining the clinical criteria of inflammatory back pain and enthesitis or arthritis with radiologic findings. [6, 7, 8]

Radiography

Radiographic evidence of inflammatory changes in the SI joints and spine are useful in the diagnosis and ongoing evaluation of AS. [9]

Early radiographic signs of enthesitis include squaring of the vertebral bodies caused by erosions of the superior and inferior margins of these bodies, resulting in loss of the normal concave contour of the bodies’ anterior surface. The inflammatory lesions at vertebral entheses may result in sclerosis of the superior and inferior margins of the vertebral bodies, called shiny corners (Romanus lesion).

Power Doppler ultrasonography can be used to document active enthesitis. In addition, this technology may be useful in the assessment of changes in inflammatory activity at entheses during the institution of new therapies. [10]

MRI and CT scanning

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scanning of the SI joints, spine, and peripheral joints may reveal evidence of early sacroiliitis, erosions, and enthesitis that are not apparent on standard radiographs. [11, 12]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Pharmacologic therapy

Agents used in the treatment of AS include the following:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

-

Sulfasalazine

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors (TNFi) – Etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol

-

Corticosteroids

-

Janus kinase inhibitors – Tofacitinib, upadacitinib

-

Interleukin 17 inhibitors (IL-17i) – Secukinumab, ixekizumab

Surgical therapy

The following procedures can be used in the surgical management of AS:

-

Vertebral osteotomy - Patients with fusion of the cervical or upper thoracic spine may benefit from extension osteotomy of the cervical spine. [13] This procedure is associated with significant complications and should rarely be performed and only by surgeons with appropriate experience.

-

Fracture stabilization

-

Joint replacement - Patients with significant involvement of the hips may benefit from total hip arthroplasty. [14]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, multisystem inflammatory disorder primarily involving the sacroiliac (SI) joints and the axial skeleton. Other clinical manifestations include peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and extra-articular organ involvement. [15, 16, 17, 18] AS has been designated by various names, including rheumatoid spondylitis in the American literature, spondyloarthrite rhizomegalique in the French literature, and the eponyms Marie-Strümpell disease and von Bechterew disease.

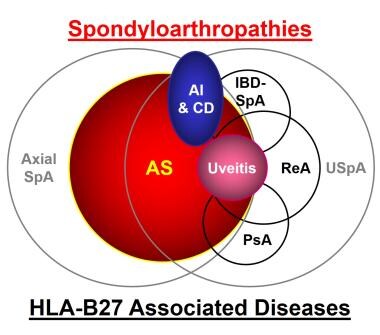

AS is the prototype of the spondyloarthropathies, a family of related disorders that also includes non-radioraphic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), reactive arthritis (ReA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), inflammatory bowel disease–associated spondyloarthropathy (IBD-SpA), undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy (USpA), and possibly Whipple disease and Behçet disease (see the image below). The spondyloarthropathies are linked by common genetics (the human leukocyte antigen [HLA] class-I gene HLA-B27) and a common pathology (enthesitis).

AS is classified as a spondyloarthropathy. The disorder is often found in association with other spondyloarthropathies, including ReA, PsA, ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn disease. Patients often have a family history of either AS or another spondyloarthropathy.

The etiology of AS is not understood completely; however, a strong genetic predisposition exists. [19, 6] A direct relationship between AS and the HLA-B27 gene has been determined. [20, 21, 22, 23] The precise role of HLA-B27 in precipitating AS remains unknown; however, one hypothesis is molecular mimicry in which HLA-B27 preferentially presents a bacterial (arthritogenic) antigen that induces an immune response to a self-antigen and autoimmunity.

The diagnosis of AS is generally made by combining clinical criteria of inflammatory back pain and enthesitis or arthritis with radiological findings. Early diagnosis is important because early medical and physical therapy may improve functional outcome. As with any chronic disease, patient education is vital to familiarize the patient with the symptoms, course, and treatment of the disease. Treatment measures include pharmacologic, physical therapy, and surgical.

Pathophysiology

The spondyloarthropathies are chronic inflammatory diseases that most commonly involve the SI joints and the axial skeleton, with hip and shoulder joints less frequently affected. Peripheral joints and entheses and certain extra-articular organs, including the eyes, skin, and cardiovascular system, may be involved to a lesser degree.

The primary pathology of the spondyloarthropathies is enthesitis with chronic inflammation, including CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophages. Cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), are also important in the inflammatory process by leading to inflammation, fibrosis, and ossification at sites of enthesitis. [24, 25, 26] The IL-23/IL-17 axis is also important in the spondyloarthropathies including the induction of Th17 cells and the production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17. [27, 28] In addition, TNF-α and IL-17 have been targeted therapeutically for the treatment of axial spondylarthritis.

The initial presentation of AS generally relates to the SI joints; involvement of the SI joints is required to establish the diagnosis. SI joint involvement is followed by involvement of the discovertebral, apophyseal, costovertebral, and costotransverse joints and the paravertebral ligaments.

Early lesions include subchondral granulation tissue that erodes the joint and is replaced gradually by fibrocartilage and then ossification. This occurs in ligamentous and capsular attachment sites to bone and is called enthesitis. [29]

In the spine, this initial process occurs at the junction of the vertebrae and the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral discs. The outer fibers of the discs eventually undergo ossification to form syndesmophytes. The condition progresses to the characteristic bamboo spine appearance.

Extra-articular involvement can include acute anterior uveitis and aortitis. Anterior uveitis occurs in 25-30% of patients and generally is acute and unilateral. Symptoms include pain, lacrimation, photophobia, and blurred vision. Chronic aortitis can lead to aortic valve insufficiency, which has been found in 18% of patients. Other cardiac complications include anterior fascicular block and left axis deviation. [30]

Pulmonary involvement is secondary to inflammation of the costovertebral and costotransverse joints, which limits chest wall range of motion (ROM). Pulmonary fibrosis is generally an asymptomatic incidental radiographic finding. Neurologic deficits are secondary to spinal fracture or cauda equina syndrome resulting from spinal stenosis. Spinal fracture is most common in the cervical spine.

Etiology

The etiology of AS is unknown, but a combination of genetic and environmental factors works in concert to produce clinical disease. [31]

Genetic predisposition

The strong association of AS with HLA-B27 is direct evidence of the importance of genetic predisposition (see Table 1 below). [20, 21, 22, 32, 33, 34, 35] Of the various genotypic subtypes of HLA-B27, HLA-B*2705 has the strongest association with the spondyloarthropathies. HLA-B*2702, *2703, *2704, and *2707 are also associated with AS. [36] People who are homozygous for HLA-B27 are at a greater risk for AS than those who are heterozygous. [37]

AS is more common in persons with a family history of AS or another seronegative spondyloarthropathy. The concordance rate in identical twins is 60% or less. HLA-B27–restricted CD8+ (cytotoxic) T cells may play an important role in bacterial-related spondyloarthropathies such as reactive arthritis. [38] An epistatic interaction between HLA-B60 and HLA-B27 increases the risk of developing AS. [39]

Table 1. Association of Spondyloarthropathies With HLA-B27 (Open Table in a new window)

Population or Disease Entity |

HLA-B27 –Positive |

Healthy whites |

8% |

Healthy African Americans |

4% |

Ankylosing spondylitis (whites) |

92% |

Ankylosing spondylitis (African Americans) |

50% |

Reactive arthritis |

60-80% |

Psoriasis associated with spondylitis |

60% |

IBD associated with spondylitis |

60% |

Isolated acute anterior uveitis |

50% |

Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy |

20-25% |

The shared amino acid sequence between the antigen-binding region of several HLA-B27 genotypic subtypes, especially HLA-B*2705, and nitrogenase from Klebsiella pneumoniae supports molecular mimicry as a possible mechanism for the induction of spondyloarthropathies in genetically susceptible hosts via an environmental stimulus, including bacteria in the GI tract. [40] The specifics of this relationship remain unclear.

Several other genes have been studied with respect to their potential involvement in the development of AS (see Table 2 below).

Table 2. Genetics of Ankylosing Spondylitis (Open Table in a new window)

Genes |

Chromosome Location |

Gene Product/Function |

Definitely or probably associated HLA-B27 HLA-B60 ERAP1 (ART1) IL23R IL-1 gene cluster IL-1R2 STAT3 |

6p21.3 6p21.3 5q151p31.1 2q12.1 2q11-12 17q21 |

Antigen presentation Antigen presentation ER aminopeptidase 1 IL-23 receptor Modulator of inflammation Decoy receptor for IL-1 Signal transduction for IL-5, 6, 11 |

Probably associated CYP 2D5 ANKH TLR4 KIR (Killer Ig-like receptor) MEFV |

22q13.1 5p15 9q32 19q13.4 16p13.3 |

Metabolism about xenobiotics Ectopic mineralization Pattern recognition receptor forLPS NK cell receptor Pyrin, innate immunity |

Not associated TGF-ß, MMP3, IL-10, IL-6, Ig allotypes, TCR, TLR4, NOD2/CARD15, CD14, NFßBIL1, PTPN22, etc |

Multiple |

Multiple |

ARTS1 is also associated with AS. This gene encodes the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase, which cleaves cytokine receptors for IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1 from the cell surface and is important in antigen presentation by class 1 major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. [41, 34, 35]

IL23R, which encodes the receptor for IL-23, is also associated with AS. [41, 42, 43, 44, 34, 35] IL-23 promotes survival of Th17 CD4+ T cells. Th17 cells play an important role in inflammatory responses by producing various proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-17, IL-6, and TNF-α) and recruiting other inflammatory cells (eg, neutrophils) in inflammatory and infectious diseases. Thus, they may play an important role cells in the pathogenesis of AS and other spondyloarthropathies. [45]

The interleukin (IL)-1 gene cluster is an important locus associated with susceptibility to AS. [46, 47] CYP 2D6 and ANKH genes are probably associated with AS. [33]

Numerous genes have been excluded in the etiology of ankylosing spondylitis, such as the following [33] :

-

TGF-β

-

MMP3

-

IL-10

-

IL-6

-

Immunoglobulin (Ig) allotypes

-

TCR

-

TLR4

-

NOD2/CARD15

-

CD14

-

NFbBIL1

-

PTPN22

Immunologic mechanisms

Another possible mechanism in the induction of AS is presentation of an arthritogenic peptide from enteric bacteria by specific HLA molecules. Many patients with AS have subclinical GI tract inflammation and elevated IgA antibodies directed against Klebsiella. The bacteria may invade the GI tract of a genetically susceptible host, leading to chronic inflammation and increased permeability. Over time, bacterial antigens containing arthritogenic peptides enter the organism via the bloodstream.

Localization of pathology to certain types of connective tissues (eg, entheses) may be explained by affinity of bacterial antigens to these specific sites. Biomechanical stress, such as that which occurs at entheses in the spine and feet, may predispose to clinical enthesitis at these sites.

The spondyloarthropathies are the only known autoimmune diseases linked to an HLA class-I rather than HLA class-II genes. The cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell response appears to be important; it would respond to antigen presented by HLA class-I molecules on the surface of cells. The association of spondyloarthropathies (eg, ReA) with HIV infection in certain areas of the world supports the relative importance of the CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses compared with the CD4+ helper cells in these conditions.

Environmental factors

AS does not develop in every person who is HLA-B27 positive; thus, it is clear that environmental factors are important. Even first-degree relatives who are HLA-B27 positive do not uniformly develop the disease. In fact, only 15-20% of such individuals develop the disease.

HLA-B27–positive transgenic rats develop an illness similar to a spondyloarthropathy, with manifestations that include sacroiliitis, enthesitis, arthritis, skin and nail lesions, ocular inflammation, cardiac inflammation, and inflammation of the gastrointestinal and male genitourinary tracts. [48] The severity of the clinical disease correlates with the number of copies of HLA-B27 expressed in the transgenic animal.

HLA-B27–positive transgenic rats that are raised in a germ-free environment do not develop clinical disease. Once introduced into a regular environment (ie, non–germ-free) and exposed to bacteria, the rats develop clinical manifestations of spondyloarthropathy. [49, 50]

Patients with AS may experience exacerbations after trauma. However, no scientific studies support trauma as a cause of AS.

Epidemiology

AS is the most common of the classic spondyloarthropathies. Prevalence varies with the prevalence of the HLA-B27 gene in a given population, which increases with distance from the equator. In general, AS is more common in whites than in nonwhites. It occurs in 0.1-1% of the general population, [51, 52, 53] with the highest prevalence in northern European countries and the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa. [36, 54, 55]

Approximately 1-2% of all people who are positive for HLA-B27 develop AS. This increases to 15-20% if they have a first-degree relative with HLA-B27 positive AS. [6, 31]

Prevalence data for nr-axSpA and USpA are scarce, although this disorder appears to be at least as common as AS, if not more so. [51] The actual prevalence may be as high as 1-2% of the general population. The prevalence of nr-axSpA geographically and among different sexes and ethnic groups is probably similar to AS but specific data are limited, as it is also associated with HLA-B27.

Age-related demographics

The age of onset of AS is usually from the late teens to age 40 years. Approximately 10%-20% of all patients experience symptom onset before age 16 years; in such patients, the disease is referred to as juvenile-onset AS. Onset of AS in persons older than 50 years is unusual, although a diagnosis of mild or asymptomatic disease may be made at a later age. [56] Uncommonly, patients may not come to medical attention until they have advanced disease.

Diagnosis is often significantly delayed, usually for several years after the onset of inflammatory rheumatic symptoms. In a study of German and Austrian patients with AS, the age of onset of disease symptoms was 25 years in HLA-B27–positive and 28 years in HLA-B27–negative patients, with a delay in diagnosis of 8.5 years in HLA-B27–positive and 11.4 years in HLA-B27–negative patients. [57]

In a study of Turkish patients with AS, the age of onset of disease symptoms was 23 years, with a delay in diagnosis of 5.3 years in HLA-B27–positive patients and 9.2 years in HLA-B27–negative patients. [58] Patients with inflammatory back pain or a positive family history of AS had a shorter diagnostic delay.

USpA is generally found in young to middle-aged adults but can develop from late childhood into the fifth decade of life. [59]

Sex-related demographics

According to radiographic survey studies, prevalence rates of AS are approximately equal in men and women. However, men have more severe radiographic changes in the spine and hips than women, [60] and clinical AS is more common in men than in women, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:1. [6, 56] Females may have milder or subclinical disease. The male-to-female ratio for USpA is 1:3. [59]

Race-related demographics

The prevalence of AS parallels the prevalence of HLA-B27 in the general population. The prevalence of HLA-B27 and AS is higher in whites and certain Native Americans than in African Americans, Asians, and other non-white ethnic groups. [36, 33] However, a study of racial differences in AS among patients in the United States found that African Americans have high disease activity and co-morbidities compared with whites. [61] AS is least prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa. The less common juvenile-onset version of AS is more common among Native Americans, Mexicans, and persons in developing countries.

USpA is not associated as strongly with HLA-B27, although it is more prevalent in whites than in nonwhite ethnic groups. [59]

Prognosis

The outcome in patients with spondyloarthropathies, including AS, is generally better compared with that in patients with a disease such as rheumatoid arthritis. Patients often require long-term anti-inflammatory therapy. Morbidity can occur from spinal and peripheral joint involvement or, rarely, extra-articular manifestations. Indicators of poor prognosis include the following:

-

Peripheral joint involvement

-

Young age of onset

-

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

-

Poor response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

At the onset of the disease, symptoms are generally unilateral and intermittent. As the disease progresses, pain and stiffness generally become more severe and more constant. Adequate exercise can improve symptoms and ROM.

Some patients have few, if any, symptoms. A significant portion of AS patients develop chronic progressive disease and develop disability due to spinal inflammation leading to fusion, often with thoracic kyphosis or erosive disease involving peripheral joints, especially the hips and shoulders. Patients with spinal fusion are prone to spinal fractures that may result in neurologic deficits. Most functional loss in AS occurs during the first 10 years of illness. [62]

Severe physical disability is not common among patients with AS. Problems with mobility occur in approximately 47% of patients. Disability is related to the duration of the disease, peripheral arthritis, cervical spine involvement, younger age at onset of symptoms, and coexisting illnesses. Disability has been demonstrated to improve with prolonged periods of exercise or surgical correction of peripheral joint and cervical spine involvement.

Most patients remain fully functional and continue working after the onset of symptoms. [63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68] Vocational counseling has been demonstrated to decrease the risk of employment disability by more than 60%. [69] Although most patients are able to continue to work, as many as 37% change occupations to less physically demanding jobs as symptoms progress.

In rare cases, patients with severe long-standing AS develop significant extra-articular manifestations such as cardiovascular disease, including cardiac conduction defects and aortic regurgitation; pulmonary fibrosis; neurologic sequelae (eg, cauda equina syndrome); or amyloidosis. Patients with severe long-standing AS have a greater risk of mortality than the general population. [62] Death is more likely in the presence of either extra-articular manifestations or coexisting diseases. [70, 71]

Emotional problems related to the disease are reported in 20% of patients. Depression is more common among women, and contributing factors include the level of pain and functional disability involved.

In some patients, nr-axSpA progresses to AS over time, but that does not happen in all cases. USpA appears to carry a good-to-excellent prognosis, although some patients have chronic symptoms associated with functional disability. Erosive arthritis is very uncommon. Uveitis occasionally occurs and may be recurrent or chronic. Patients who develop sacroiliitis and spondylitis, by definition, have AS. [72, 59]

Patient Education

Patient education is essential in disease management. Teach patients about the long-term nature of the illness and the use and toxicities of medications. Inform patients that proper exercise programs are useful in reducing symptoms and increasing ROM. For patient education information, see the Ankylosing Spondylitis Directory.

Because of the joint involvement in the chest wall and the potential for pulmonary complications, include smoking cessation in recommendations. One 2011 study found that a history of smoking was associated with higher disease activity and decreased function in AS. [73]

Genetic counseling is useful in assisting patients with questions regarding the risk of family members developing AS or other seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Various patient support groups are available to assist in the education of these patients (eg, Spondylitis Association of America support groups).

-

This 15-year-old female patient presented with recent onset of right-sided low back pain. Plain radiography findings were normal.

-

MRI of the same patient whose radiography findings were normal (previous image). She underwent further evaluation, including MRI. The MRI (short tau inversion recovery [STIR]) showed increased sinal intensity in the right sacroiliac joint, revealing sacroiliitis. Other laboratory study findings were essentially normal. The patient was started on indomethacin and rapidly improved.

-

Patient with ankylosing spondylitis affecting cervical and upper thoracic spine. The patient's spine has been fused in flexed position.

-

Posterior view of a patient with ankylosing spondylitis affecting cervical and upper thoracic spine. The patient's spine has been fused in a flexed position.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of spine of a patient with AS. Ossification of annulus fibrosus can be observed at multiple levels, which has led to fusion of spine with abnormal curvature.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of spine of a patient with AS.

-

Anteroposterior (left) and lateral (right) radiographs of a patient with AS.

-

Radiographs of hand (top) and arm (bottom) of a patient with peripheral involvement of AS. Fusion of joint spaces and deformity can be observed.

-

Sagittal MRI of thoracolumbar spine of a patient with AS. Syndesmophytes and anterior corner lesions can be seen.

-

Radiograph shows vertebral fracture in a patient with AS.

-

This radiograph of the lumbar spine of a patient with end-stage AS shows bridging syndesmophytes, resulting in bamboo spine.

-

This radiograph of the cervical spine of a patient with AS shows fusion of the vertebral bodies due to bridging syndesmophytes.

-

ASAS Classification Criteria for Axial Spondyloarthropathy.

-

ASAS Classification Criteria for Peripheral Spondyloarthropathy.

-

Family of spondyloarthropathies and HLA-B27 associated diseases

-

Bilateral symmetric sacroiliitis in a patient with AS showing blurring of the margins of the joints and pseudo-widening.

-

Bilateral symmetric sacroiliitis in a patient with AS with narrowing and sclerosis of the joints.

-

Bilateral sacroiliac joint fusion in a patient with AS.

-

Enthesitis at the site of the insertion of the annulus fibrosis on the corners of the vertebral bodies, shiny corner (Romanus) lesions.

-

CT scan of the pelvis in a patient with AS showing ankylosis of the sacroiliac joints.

-

CT scan of the L-spine in a patient with AS showing bony syndesmophytes.