Practice Essentials

Cryptosporidiosis is an infection caused by the protozoan Cryptosporidium, transmitted via the fecal-oral route. [64] The primary symptom is watery diarrhea, often accompanied by other gastrointestinal distress. In immunocompetent individuals, the illness usually is self-limiting, but it can be severe and persistent in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), particularly those with advanced disease. Diagnosis is made by identifying the organism or its antigen in stool samples. Treatment for immunocompetent patients, when needed, involves oral nitazoxanide. For patients with HIV, highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) and supportive care are essential; although oral nitazoxanide may alleviate symptoms, it does not guarantee a cure, especially in those with end-stage HIV.

Background

Human cryptosporidiosis is caused by infection with apicomplexan protozoa of the genus Cryptosporidium. [1, 2, 3] Human illness formerly was thought to be caused by a single species, but molecular studies have demonstrated that it is caused by at least 15 different species. Among the more common species are Cryptosporidium hominis, for which humans are the only natural host, and Cryptosporidium parvum, which infects a range of mammals as well as humans. [1, 2] (See Etiology and Pathophysiology.)

Cryptosporidiosis mainly affects children. It causes a self-limited diarrheal illness in healthy adults. However, it also is recognized as a cause of prolonged and persistent diarrhea in children, which can result in malnutrition. [4, 5] Cryptosporidiosis can present as a chronic, severe diarrhea in persons with AIDS, solid and bone marrow transplants or immunosuppression due to chemotherapy/immunotherapy. [6] (See Prognosis and Presentation.) Cryptosporidium also can cause waterborne, and, less frequently, foodborne outbreaks. (See Epidemiology, Workup, and Treatment.)

The genus Cryptosporidium consists of a group of protozoan parasites within the phylum Apicomplexa. To date there are at least 44 validated species of Cryptosporidium, recognized by host specificity, morphology, and molecular biology studies. [3, 7, 9, 10] Besides humans, the parasite can infect many other species of animals, such as mammals, birds, and reptiles, and is pathogenic to immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts (see the image below).

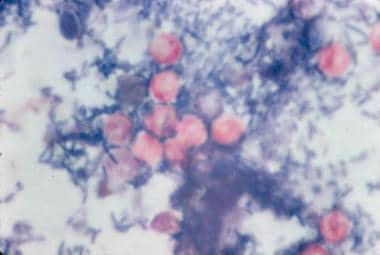

Modified acid-fast stain of stool shows red oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum against the blue background of coliforms and debris.

Modified acid-fast stain of stool shows red oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum against the blue background of coliforms and debris.

See Common Intestinal Parasites, a Critical Images slideshow, to help make an accurate diagnosis.

Cryptosporidium species that infect humans replicate in the epithelial cell lining of the GI tract. They can complete their entire life cycle within a single host, but some species also can spread between host species. [1, 2, 11] C hominis and C parvum cause most human infections. Both can be spread from person to person. C parvum also can be zoonotic. Other species can infect humans but are less common such as C cuniculus, C meleagridis, C tyzzeri, and C viatorum. [11]

Transmission

The disease is transmitted via the fecal-oral route from infected hosts. [1] Most sporadic infections occur through person-to-person contact. Nonetheless, transmission can occur following animal contact, ingestion of water (mainly during swimming), or through food. Waterborne outbreaks have resulted from contamination of municipal water and recreational waters (eg, swimming pools, ponds, lakes). [3, 9, 10] Animal contact can also be associated with transmission of zoonotic species. [9, 11] (See Etiology and Treatment.)

Cryptosporidium has emerged as the most frequently recognized cause of recreational water–associated outbreaks of gastroenteritis, particularly in treated (disinfected) venues. [13] This is because in the oocyst stage of its life cycle, Cryptosporidium can resist disinfection, including chlorination, and can survive for a prolonged period in the environment.

Life cycle

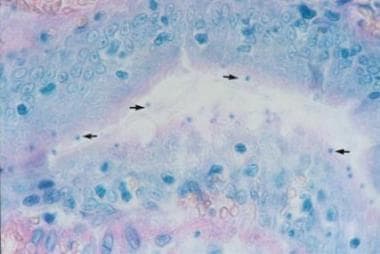

Cryptosporidium species do not multiply outside the host. [1, 2] Infection is initiated by ingestion of oocysts, which are activated in the stomach and upper intestines to release four infective sporozoites (see the first image below). These motile sporozoites bind to the receptors on the surface of the intestinal epithelial cells (see the second image below) and are ingested into a parasitophorous vacuole near the surface of the epithelial cell, separated from the cytoplasm by a dense layer. Cryptosporidium oocysts are round and measure 4.2-5.4 µm in diameter.

Cryptosporidium species oocysts are rounded and measure 4.2-5.4 µm in diameter. Sporozoites are sometimes visible inside the oocysts, indicating that sporulation has occurred on wet mount.

Cryptosporidium species oocysts are rounded and measure 4.2-5.4 µm in diameter. Sporozoites are sometimes visible inside the oocysts, indicating that sporulation has occurred on wet mount.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of intestinal epithelium. The blue dots (arrows) represent intracellular Cryptosporidium organisms along the surface of the epithelial cells. Image courtesy of Carlos Abramowsky, MD, Professor of Pediatrics and Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of intestinal epithelium. The blue dots (arrows) represent intracellular Cryptosporidium organisms along the surface of the epithelial cells. Image courtesy of Carlos Abramowsky, MD, Professor of Pediatrics and Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine.

Once inside the epithelial cell, the parasites enlarge, divide, and reinvade other cells in a series of sexual and asexual multiplication steps eventually leading to the production of oocysts. Two morphologic forms of the oocysts have been described: thin-walled oocysts (asexual stage) excyst within the same host (causing self-infection), whereas the thick-walled oocysts (sexual stage) are shed into the environment. Oocyst shedding can continue for weeks after a patient experiences clinical improvement.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Cryptosporidium oocysts are highly infectious, requiring < 10 oocysts to cause human disease for some isolates. [13, 14, 15] The oocysts are infectious immediately after excretion, and the life cycle of the parasite produces forms that reinvade the intestine. The location of the parasite in the intestine is intracellular but extra cytoplasmic, which may contribute to the marked resistance of Cryptosporidium species to treatment. Large numbers of oocysts are excreted and are resistant to harsh conditions, including chlorine at levels usually applied in water treatment.

Cryptosporidiosis typically presents with watery diarrhea. The mechanism by which Cryptosporidium causes diarrhea includes a combination of increased intestinal permeability, chloride secretion, and malabsorption, which all are thought to be mediated by the host response to infection. [2] Severe disease is characterized by villous atrophy and crypto hyperplasia. [14] 14 In immunocompetent persons, the infection is usually limited to the small intestine, however in immunocompromised individuals infection can be pan-enteric to ileo-colonic.15 In persons with AIDS or certain congenital immunodeficiencies, the biliary tract and respiratory tract may be involved.16

Cryptosporidium oocysts are highly infectious, requiring < 10 oocysts to cause human disease for some isolates. [15, 16] The oocysts are infectious immediately after excretion, and the life cycle of the parasite produces forms that reinvade the intestine. The location of the parasite in the intestine is intracellular but extra cytoplasmic, which may contribute to the marked resistance of Cryptosporidium species to treatment. Large numbers of oocysts are excreted and are resistant to harsh conditions, including chlorine at levels usually applied in water treatment. Cryptosporidiosis typically presents with watery diarrhea The mechanism by which Cryptosporidium causes diarrhea includes a combination of increased intestinal permeability, chloride secretion, and malabsorption, which are all thought to be mediated by the host response to infection. [2, 17] In addition, it is thought to cause a change on microbiome diversity. [18] Severe disease is characterized by villous atrophy and crypto hyperplasia. [19] In immunocompetent persons, the infection is usually limited to the small intestine, however in immunocompromised individuals infection can be pan-enteric to ileo-colonic. [20] In persons with AIDS or certain congenital immunodeficiencies, the biliary tract and respiratory tract may be involved. [21]

Risk factors

Among healthy individuals, cryptosporidiosis is primarily a disease of children. Daycare center-related outbreaks have a high infection rate (30-60%). Risk groups include childcare workers; parents of infected children; international travelers, including backpackers and hikers who drink unfiltered, untreated water; swimmers who swallow contaminated recreational water; people who handle infected animals; and people exposed to human feces through sexual contact. [1, 2, 8, 10, 22, 23, 24] Individuals with compromised cellular immunity are at increased risk for symptomatic cryptosporidiosis, particularly for more severe disease. [6] Immunodeficiency may be congenital (especially Hyper IgM syndrom) or may be secondary to HIV infection, malnutrition, or organ trasnplantation. [26, 27]

Pregnancy is another predisposing factor for cryptosporidiosis. In resource-limited nations, the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection is significantly higher than in industrialized countries because of a lack of clean water and sanitary facilities, crowding, and animal reservoirs near residences. In a systematic review in low- and middle-income countries overcrowding, diarrhea in household and animal contact were the major risk factors for infection, [5] whereas a survey-based study in Africa demonstrated water sources as a significant risk factor for the infection. [28]

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

The frequency of cryptosporidiosis has not been well-defined in the United States. Many laboratories do not routinely test for Cryptosporidium. Laboratories that test for Cryptosporidium often use insensitive tests. [1, 2] The number of reported cases has increased with increased awareness and improved diagnostic testing. In 2022, there were 10,169 cases of confirmed cryptosporidiosis according to CDC. [29] Studies in the United States have documented cryptosporidiosis in about 4% of stools sent for parasitologic examination. Seroprevalence studies in the United States suggest that 21.2% of the population older than 6 years had cryptosporidiosis at some time in their life with higher odds in low-income households. [30] Cryptosporidium species is associated to waterborne outbreaks of diarrhea. The most significant outbreak was in 1993, when more than 400,000 cases of diarrheal illness due to Cryptosporidium infection were reported in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. [31] For the period 2015–2019, a total of 208 outbreaks associated with treated recreational water were reported to the CDC. Cryptosporidium caused 76 outbreaks, resulting in 2492 cases. [34] Waterborne outbreaks continue to be reported worldwide in industrialized countries. [32, 33, 34]

Cryptosporidium parasites are ubiquitous, except in Antarctica, and infection is more common in warm, moist months. [1, 29] In the United States, incidence peaks from July through September. In England there are separate peaks in the spring (associated with C parvum and farm animals) and the fall (associated with C hominis and recreational water). [9, 35] Outbreaks in daycare centers with incidence rates of 30-60% have been reported. [24] Prior to the availability of combination antiretroviral therapy, approximately 10-15% of patients with AIDS developed cryptosporidiosis over their lifetime. Although the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients has dropped dramatically, it continues to be prevalent in the HIV/AIDS population. [36, 37]

International statistics

Cryptosporidiosis is a notifiable disease at the European Union level, and surveillance data are collected through the European Basic Surveillance Network. [35] The crude incidence rate was similar to that in the United States, with six countries accounting for 94% of confirmed cases, although considerable differences in the rates of cryptosporidiosis were observed between countries and over time. [35] In resource-limited countries, most infections are in children. In a large multicenter study of moderate to severe diarrhea in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, Cryptosporidium was second to rotavirus as a cause of diarrhea in children younger than 2 and associated with 200,000 deaths. [38] A multicenter birth cohort study from Asia, Africa, and Latin America (the malnutrition and enteric disease study) also found Cryptosporidium was among the top causes of diarrheal disease and non-diarrheal infection was associated with malnutrition. [5, 38] Studies suggest that the burden of disease related to malnutrition may be greater than that due to diarrhea. [4, 39] Rates are often higher when molecular tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used. [38, 40] In persons with AIDS, cryptosporidiosis si more common in developing countries, ranging from 12-26% of persons with AIDS who have diarrhea. [41, 42, 43, 44] Data about incidence and prevalence of infection in solid and bone marrow organ transplant are limited. A few retrospective case reports in renal transplant recipients report a prevalence between 4.5% and 53%. [21]

Age-related demographics

The peak incidence of cryptosporidiosis is in children younger than 5 years. [1, 2, 3, 4] Infection is infrequently diagnosed in immunocompetent adults in resource-limited countries. A second peak includes women of childbearing age (likely due to contact with infected children). [1, 45] Cryptosporidiosis can occur in persons with AIDS of any age. [42, 44] Children younger than 2 years may be more susceptible to infection, possibly because of increased fecal-oral transmission in this age group and because of a lack of protective immunity. [39] Waterborne epidemics in industrialized countries affect all ages. [32, 33, 34]

Prognosis

In most healthy individuals, Cryptosporidium-induced diarrhea usually is self-limited. However, diarrhea is often prolonged (>1 week) or persistent (>2 weeks). In patients who are severely immunocompromised and young children, cryptosporidiosis may be chronic, severe, and sometimes, fatal. [41, 46] Individuals with AIDS and cryptosporidiosis tend to develop chronic symptoms more often and about 10% have a fulminant course. [1, 31] Antiretroviral treatment improves outcome.

Immunocompetent individuals infected with Cryptosporidium generally do well. However, persistent abdominal pain, loose stools, and extraintestinal sequelae (eg, joint pain, eye pain, headache, dizzy spells, fatigue), especially with C hominis infection. Symptoms have been reported at 12 months post infection in children and adults, associated with a threefold risk for reporting any symptoms 10 years post-infection. [47, 48]

Morbidity and Mortality

Complications of cryptosporidiosis include the following:

Patient Education

Thorough hand washing should be practiced by patients with diarrhea to avoid the spread of the disease. The effectiveness of alcohol-based hand sanitizers has not been well studied, and their use should not be recommended.

Subjects with diarrhea should avoid using public swimming pools during their illness and at least 2 weeks after diarrhea has subsided.

Encourage immunocompromised patients to consider using 1-μm water filters when drinking tap water. Also consider boiled or bottled drinking water for patients who are immunocompromised, particularly those with HIV who have fewer than 200 CD4 cells/µL. Persons living in countries with a high risk of transmission should also be encouraged to use bottled or filtered water.

Immunocompromised patients (eg, patients with AIDS or solid organ transplant recipients) should avoid newborn animals (eg, calves, lambs), including domestic animals, and people with diarrhea. They should also consider avoiding communal recreational water such as public swimming pools. New pets for patients with AIDS should be older than 6 months and should not have diarrhea.

Instruct patients with AIDS, daycare workers, food handlers, and healthcare workers to avoid fecal-oral spread by wearing gloves and washing their hands after contact with human feces. Spread can occur after activities such as changing diapers.

-

Modified acid-fast stain of stool shows red oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum against the blue background of coliforms and debris.

-

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of intestinal epithelium. The blue dots (arrows) represent intracellular Cryptosporidium organisms along the surface of the epithelial cells. Image courtesy of Carlos Abramowsky, MD, Professor of Pediatrics and Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine.

-

Cryptosporidium species oocysts are rounded and measure 4.2-5.4 µm in diameter. Sporozoites are sometimes visible inside the oocysts, indicating that sporulation has occurred on wet mount.

-

Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts revealed with modified acid-fast stain. Against a blue-green background, the oocysts stand out with a bright red stain. Image courtesy of CDC DPDx parasite image library.

-

Cryptosporidium oocysts revealed with modified acid-fast stain.