Background

Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to a range of neurological manifestations, including cognitive impairment, peripheral neuropathy, and myelopathy. [1, 2] These symptoms are often seen in patients with megaloblastic anemia, and the association between B12 deficiency and neurological dysfunction has been recognized for over a century. Notably, subacute combined degeneration (SCD) of the spinal cord, a hallmark of B12 deficiency, presents with symptoms like numbness, weakness, and gait disturbances. In addition to B12 deficiency related to dietary causes, neurological complications can also arise from malabsorption conditions, such as pernicious anemia or prolonged nitrous oxide exposure. Timely recognition and treatment are essential to prevent irreversible neurological damage.

See the image below.

Pathophysiology

Vitamin B12 structure

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is a complex molecule in which a cobalt atom is contained in a corrin ring. Vitamin B12 is available in animal protein.

Body stores

Total body stores are 2–5 mg, of which half is stored in the liver. The recommended daily intake is 2 mcg/d in adults; pregnant and lactating women require 2.6 mcg/d. Children require 0.7 mcg/d and, in adolescence, 2 mcg/d. Because vitamin B12 is highly conserved through the enterohepatic circulation, cobalamin deficiency from malabsorption develops after 2–5 years and deficiency from dietary inadequacy in vegetarians develops after 10–20 years. Its causes are mainly nutritional and malabsorptive, pernicious anemia (PA) being most common.

Physiology of absorption

After ingestion, the low stomach pH cleaves cobalamin from other dietary protein. [3] The free cobalamin binds to gastric R binder, a glycoprotein in saliva, and the complex travels to the duodenum and jejunum, where pancreatic peptidases digest the complex and release cobalamin. Free cobalamin can then bind with gastric intrinsic factor (IF), a 50-kd glycoprotein produced by the gastric parietal cells, the secretion of which parallels that of hydrochloric acid. Hence, in states of achlorhydria, IF secretion is reduced, leading to cobalamin deficiency. Importantly, only 99% of ingested cobalamin requires IF for absorption. Up to 1% of free cobalamin is absorbed passively in the terminal ileum. This why oral replacement with large vitamin B12 doses is appropriate for PA.

Once bound with IF, vitamin B12 is resistant to further digestion. The complex travels to the distal ileum and binds to a specific mucosal brush border receptor, cublin, which facilitates the internalization of cobalamin-IF complex in an energy-dependent process. Once internalized, IF is removed and cobalamin is transferred to other transport proteins, transcobalamin I, II, and III (TCI, TCII, TCIII). Eighty percent of cobalamin is bound to TCI/III, whose role in cobalamin metabolism is unknown. The other 20% binds with TCII, the physiologic transport protein produced by endothelial cells. Its half-life is 6–9 min, thus delivery to target tissues is rapid.

The cobalamin-TCII complex is secreted into the portal blood where it is taken up mainly in the liver and bone marrow as well as other tissues. Once in the cytoplasm, cobalamin is liberated from the complex by lysosomal degradation. An enzyme-mediated reduction of the cobalt occurs by cytoplasmic methylation to form methylcobalamin or by mitochondrial adenosylation to form adenosylcobalamin, the two metabolically active forms of cobalamin.

Vitamin B12 role in bone marrow function

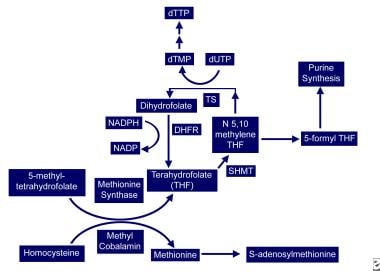

In the cytoplasm, methylcobalamin (see image below) serves as cofactor for methionine synthesis by allowing transfer of a methyl group from 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (5-methyl-THF) to homocysteine (HC), forming methionine and demethylated tetrahydrofolate (THF). This results in reduction in serum homocysteine, which appears to be toxic to endothelial cells. Methionine is further metabolized to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM).

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Cobalamin and folate metabolism. TS = thymidylate synthase, DHFR = dihydrofolate reductase, SHMT = serine methyl-transferase.

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Cobalamin and folate metabolism. TS = thymidylate synthase, DHFR = dihydrofolate reductase, SHMT = serine methyl-transferase.

THF is used for DNA synthesis. After conversion to its polyglutamate form, THF participates in purine synthesis and the conversion of deoxyuridylate (dUTP) to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP), which is then phosphorylated to deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP). dTTP is required for DNA synthesis; therefore, in vitamin B12 deficiency, formation of dTTP and accumulation of 5-methyl-THF is inadequate, trapping folate in its unusable form and leading to retarded DNA synthesis. RNA contains dUTP (deoxyuracil triphosphate) instead of dTTP, allowing for protein synthesis to proceed uninterrupted and resulting in macrocytosis and cytonuclear dissociation.

Because folate deficiency causes macrocytosis and cytonuclear dissociation via the same mechanisms, both deficiencies lead to megaloblastic anemia and disordered maturation in granulocytic lineages; therefore, folate supplementation can reverse the hematologic abnormalities of vitamin B12 deficiency but has no impact on the neurologic abnormalities of vitamin B12 deficiency, indicating both result from different mechanisms.

Vitamin B12 role in the peripheral and central nervous systems

The neurologic manifestation of cobalamin deficiency is less well understood. CNS demyelination may play a role, but how cobalamin deficiency leads to demyelination remains unclear. Reduced SAM or elevated methylmalonic acid (MMA) may be involved.

SAM is required as the methyl donor in polyamine synthesis and transmethylation reactions. Methylation reactions are needed for myelin maintenance and synthesis. SAM deficiency results in abnormal methylated phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine, and it is linked to central myelin defects and abnormal neuronal conduction, which may account for the encephalopathy and myelopathy. In addition, SAM influences serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine synthesis. This suggests that, in addition to structural consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency, functional effects on neurotransmitter synthesis that may be relevant to mental status changes may occur. Parenthetically, SAM is being studied as a potential antidepressant.

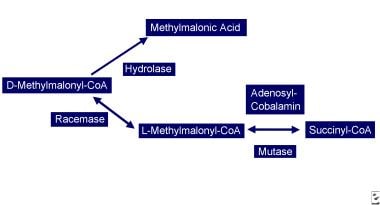

Another possible cause of neurologic manifestations involves the other metabolically active form of cobalamin, adenosylcobalamin (see image below), a mitochondrial cofactor in the conversion of L-methylmalonyl CoA to succinyl CoA. Vitamin B12 deficiency leads to an increase in L-methylmalonyl-CoA, which is converted to D-methylmalonyl CoA and hydrolyzed to MMA. Elevated MMA results in abnormal odd chain and branched chain fatty acids with subsequent abnormal myelination, possibly leading to defective nerve transmission.

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Cobalamin deficiency leads to reduced adenosylcobalamin, which is required for production of succinyl-CoA. D-methylmalonyl-CoA is converted to methylmalonic acid.

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Cobalamin deficiency leads to reduced adenosylcobalamin, which is required for production of succinyl-CoA. D-methylmalonyl-CoA is converted to methylmalonic acid.

More recent studies propose a very different paradigm: B12 and its deficiency impact a network of cytokines and growth factors, ie, brain, spinal cord, and CSF TNF-alpha; nerve growth factor (NGF), IL-6 and epidermal growth factor (EGF), some of which are neurotrophic, others neurotoxic. Vitamin B12 regulates IL-6 levels in rodent CSF. In rodent models of B12 deficiency parenteral EGF or anti-NGF antibody injection prevents, like B12 itself, the SCD-like lesions.

In the same models, the mRNAs of several cell-type specific proteins (glial fibrillary acidic protein, myelin basic protein) are decreased in a region specific manner in the CNS, but, in the PNS myelin, protein zero and peripheral myelin protein 22 mRNA remain unaltered.

In human and rodent serum and CSF, concomitantly with a vitamin B12 decrease, EGF levels are decreased, while at the same time, TNF-alpha increases in step with homocysteine levels. These observations provide evidence that the clinical and histological changes of vitamin B12 deficiency may result from up-regulation of neurotoxic cytokines and down-regulation of neurotrophic factors. [4]

Nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (N2O) can oxidize the cobalt core of vitamin B12 from a 1+ to 3+ valance state, rendering methylcobalamin inactive, inhibiting HC conversion to methionine and depleting the supply of SAM. Patients with sufficient vitamin B12 body stores can maintain cellular functions after N2O exposure, but in patients with borderline or low vitamin B12 stores, this oxidation may be sufficient to precipitate clinical manifestations.

Epidemiology

Frequency

The prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency is difficult to ascertain because of diverse etiologies and different assays (ie, radioassay or chemiluminescence). According to reports, approximately 1.5% to 15% of people have vitamin B12 deficiency. [5]

Most people in the United States consume adequate amounts of vitamin B12. Data from the 2017–2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) survey show average daily intakes of 5.84 mcg for men and 3.69 mcg for women aged 20 and older, with only 5% of men and 11% of women consuming less than the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) of 2 mcg. [6] However, those at higher risk of deficiency include individuals with low socioeconomic status, women, and non-Hispanic Blacks. [7]

Approximately 24% of men and 29% of women report using B12 supplements, with higher usage seen in children and adolescents, especially among younger age groups. Supplement users have significantly higher mean daily B12 intakes, ranging from 297.3 mcg in men to 407.4 mcg in women. [6]

Despite adequate intake for most, about 3.6% of adults and 3.7% of those older than 60 years have clinically defined vitamin B12 deficiency (serum B12 < 200 pg/mL), while B12 insufficiency (serum B12 < 300 pg/mL) is more common, affecting 12.5% of all adults and 12.3% of older adults. [8] Vitamin B12 levels may drop during pregnancy but typically normalize postpartum.

Mortality/Morbidity

Vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with an elevated homocysteine.

The prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in the general population is 5–10%; in people older than 65 years it may reach 30–40%. Elevated homocysteine is a risk factor for coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and venous thrombosis. About 10% of the vascular disease risk in the general population is linked to homocysteine.

Case-control studies have reported a correlation between multi-infarct dementia or dementia of the Alzheimer type and elevated homocysteine; vitamin B12 supplementation had no clinical benefit.

Neural tube defects are associated with low folate and vitamin B12.

Patient with pernicious anemia (PA) have a 3 times and 13 times increased risk of gastric carcinoma and gastric carcinoid tumors, respectively.

Patients with diabetes One study noted a 22% prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. [9]

Multifactorial abnormalities of vitamin B12 metabolism and absorption occur in HIV infection.

Demographics

PA prevalence may be higher in White people and lower in Hispanic and Black people.

No known relationship exists between neurologic symptoms and race.

Studies in Africa and the United States have shown higher vitamin B12 and transcobalamin II levels in black than in white individuals. Additionally, blacks have lower homocysteine levels and metabolize it more efficiently than whites.

In Europe and Africa, the prevalence of PA is higher in elderly women than men (1.5:1), while in the United States no differences exist.

Men have higher homocysteine levels at all ages.

Pregnancy and estrogen replacement in postmenopausal women lower homocysteine levels.

PA occurs in people of all ages, but it is more common in people older than 40–70 years and, in particular, in people older than 65 years.

In White people, the mean age of onset is 60; in Black people, the mean age is 50 years.

Congenital PA manifests in children aged 9 months to 10 years; the mean age is 2 years.

Prognosis

Therapy with vitamin B12 in subacute combined degeneration stops progression and improves neurologic deficit in most patients. [10]

Younger patients with less severe disease and short duration illness do better.

In a large retrospective review of 57 patients with subacute combined degeneration, absence of sensory level, absent Rhomberg sign, and flexor planter reflex were associated with good prognosis. [11]

On spinal MRI, involvement of less than seven spinal segments, cord swelling, and enhancement, but not cord atrophy, were associated with better prognosis. [11]

Clinical improvement is most pronounced in the first 2 months but continues up to 6 months.

-

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Cobalamin and folate metabolism. TS = thymidylate synthase, DHFR = dihydrofolate reductase, SHMT = serine methyl-transferase.

-

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Cobalamin deficiency leads to reduced adenosylcobalamin, which is required for production of succinyl-CoA. D-methylmalonyl-CoA is converted to methylmalonic acid.

-

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Pernicious anemia. Characteristic lemon-yellow pallor with raw beef tongue lacking filiform papillae. Photo from Forbes and Jackson with permission.

-

Vitamin B-12–associated neurological diseases. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (Flair) MRI sequence in a patient with cobalamin deficiency and neuropsychiatric manifestations. Discrete areas of hyperintensities are present in the corona radiata.