Practice Essentials

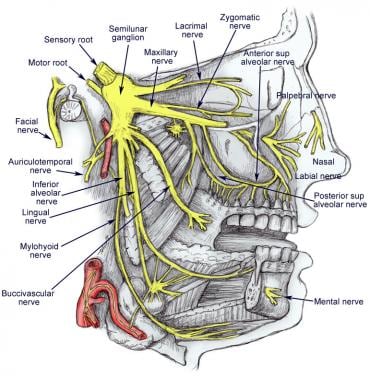

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN), also known as tic douloureux, is a distinctive facial pain syndrome that may become recurrent and chronic. It is characterized by unilateral pain following the sensory distribution of cranial nerve V (typically radiating to the maxillary or mandibular area in 35% of affected patients) and is often accompanied by a brief facial spasm or tic. See the image below.

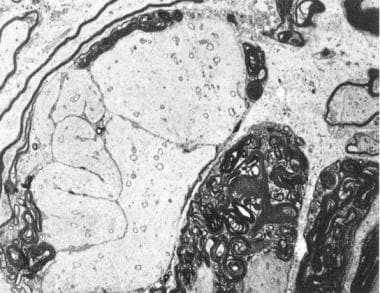

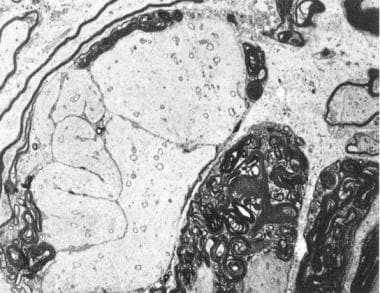

Microscopic demonstration of demyelination in primary trigeminal neuralgia. A tortuous axon is surrounded by abnormally discontinuous myelin. (Electron microscope; 3300×).

Microscopic demonstration of demyelination in primary trigeminal neuralgia. A tortuous axon is surrounded by abnormally discontinuous myelin. (Electron microscope; 3300×).

Signs and symptoms

TN presents as attacks of stabbing unilateral facial pain, most often on the right side of the face. The number of attacks may vary from less than 1 per day to 12 or more per hour and up to hundreds per day.

Triggers of pain attacks include the following:

-

Chewing, talking, or smiling

-

Drinking cold or hot fluids

-

Touching, shaving, brushing teeth, blowing the nose

-

Encountering cold air from an open automobile window

Pain localization is as follows:

-

Patients can localize their pain precisely

-

The pain commonly runs along the line dividing either the mandibular and maxillary nerves or the maxillary and ophthalmic portions of the nerve

-

In 60% of cases, the pain shoots from the corner of the mouth to the angle of the jaw

-

In 30%, pain jolts from the upper lip or canine teeth to the eye and eyebrow, sparing the orbit itself

Background

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN), also known as tic douloureux, is a common and potentially disabling pain syndrome, the precise pathophysiology of which remains obscure. This condition has been known to drive patients with trigeminal neuralgia to the brink of suicide. Although neurologic examination findings are normal in patients with the idiopathic variety, the most common type of facial pain neuralgia, the clinical history is distinctive. Trigeminal neuralgia is characterized by unilateral pain following the sensory distribution of cranial nerve V—typically radiating to the maxillary (V2) or mandibular (V3) area in 35% of affected patients (see the image below)—often accompanied by a brief facial spasm or tic. Isolated involvement of the ophthalmic division is much less common (2.8%).

Typically, the initial response to carbamazepine therapy is diagnostic and successful. Despite obtaining this satisfying early relief with medication, patients may experience breakthrough pain that requires additional drugs and, in some patients, one or more of a variety of surgical interventions.

Anatomy

The trigeminal nerve is the largest of all the cranial nerves. It exits laterally at the mid-pons level and has two divisions—a smaller motor root (portion minor) and a larger sensory root (portion major). The motor root supplies the temporalis, pterygoid, tensor tympani, tensor palati, mylohyoid, and anterior belly of the digastric. The motor root also contains sensory nerve fibers that particularly mediate pain sensation.

The gasserian ganglion is located in the trigeminal fossa (Meckel cave) of the petrous bone in the middle cranial fossa. It contains the first-order general somatic sensory fibers that carry pain, temperature, and touch. The peripheral processes of neurons in the ganglion form the 3 divisions of the trigeminal nerve (ie, ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular). The ophthalmic division exits the cranium via the superior orbital fissure; the maxillary and mandibular divisions exit via the foramen rotundum and foramen ovale, respectively.

The proprioceptive afferent fibers travel with the efferent and afferent roots. They are peripheral processes of unipolar neurons located centrally in the mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal nerve.

The image below depicts the anatomy of the trigeminal nerve.

Pathophysiology

Because the exact pathophysiology remains controversial, the etiology of trigeminal neuralgia (TN) may be central, peripheral, or both. The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) can cause pain, because its major function is sensory. Usually, no structural lesion is present (85%), although many investigators agree that vascular compression, typically venous or arterial loops at the trigeminal nerve entry into the pons, is critical to the pathogenesis of the idiopathic variety. This compression results in focal trigeminal nerve demyelination. The etiology is labeled idiopathic by default and is then categorized as classic trigeminal neuralgia.

Neuropathic pain is the cardinal sign of injury to the small unmyelinated and thinly myelinated primary afferent fibers that subserve nociception. The pain mechanisms themselves are altered. Microanatomic small and large fiber damage in the nerve, essentially demyelination, [2] commonly observed at its root entry zone (REZ), leads to ephaptic transmission, in which action potentials jump from one fiber to another. [3] A lack of inhibitory inputs from large myelinated nerve fibers plays a role. Additionally, a reentry mechanism causes an amplification of sensory inputs. A clinical correlate, for instance, is the potential for vibration to trigger an attack. However, features also suggest an additional central mechanism (eg, delay between stimulation and pain, refractory period).

Etiology

Although a questionable family clustering exists, trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is most likely multifactorial.

Most cases of trigeminal neuralgia are idiopathic, but compression of the trigeminal roots by tumors or vascular anomalies may cause similar pain, as discussed in Pathophysiology. In one study, 64% of the compressing vessels were identified as an artery, most commonly the superior cerebellar (81%). [4] Venous compression was identified in 36% of cases. [4]

Trigeminal neuralgia is divided into two categories: classic and symptomatic. The classic form, considered idiopathic, actually includes the cases that are due to a normal artery present in contact with the nerve, such as the superior cerebellar artery or even a primitive trigeminal artery.

Symptomatic forms can have multiple origins. Aneurysms, tumors, chronic meningeal inflammation, or other lesions may irritate trigeminal nerve roots along the pons causing symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia. An abnormal vascular course of the superior cerebellar artery is often cited as the cause. Uncommonly, an area of demyelination from multiple sclerosis may be the precipitant (see the following image); lesions in the pons at the root entry zone of the trigeminal fibers have been demonstrated. These lesions may cause a similar pain syndrome as in trigeminal neuralgia.

Microscopic demonstration of demyelination in primary trigeminal neuralgia. A tortuous axon is surrounded by abnormally discontinuous myelin. (Electron microscope; 3300×).

Microscopic demonstration of demyelination in primary trigeminal neuralgia. A tortuous axon is surrounded by abnormally discontinuous myelin. (Electron microscope; 3300×).

Tumor-related causes of trigeminal neuralgia (most commonly in the cerebello-pontine angle) include acoustic neurinoma, chordoma at the level of the clivus, pontine glioma or glioblastoma, [5] epidermoid, metastases, and lymphoma. Trigeminal neuralgia may result from paraneoplastic etiologies.

Vascular causes include a pontine infarct and arteriovenous malformation or aneurysm in the vicinity.

Inflammatory causes include multiple sclerosis (common), sarcoidosis, and Lyme disease neuropathy.

Infrequently, adjacent dental fillings composed of dissimilar metals may trigger attacks, [6] and one atypical case followed tongue piercing. Another case report of trigeminal neuralgia was reported in a patient with spontaneous intracranial hypotension; both conditions resolved following surgical treatment of a cervical root sleeve dural defect. [7]

Epidemiology

Trigeminal neuralgia has an incidence of 4 to 29 cases per 100,000 person-years, according to population studies in the US and UK. [8, 9, 10] This corresponds to approximately 12,000 to 87,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the US. The condition is more common in females, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:2, [8] and its prevalence increases with age, with a mean onset between 53 and 57 years. Patients who present with the disease when aged 20–40 years are more likely to suffer from a demyelinating lesion in the pons secondary to multiple sclerosis; younger patients also tend to have symptomatic or secondary trigeminal neuralgia. There have also been occasional reports of pediatric cases of trigeminal neuralgia. The estimated lifetime prevalence ranges from 0.16% to 0.3%. [8]

Approximately 1% of patients with multiple sclerosis develop trigeminal neuralgia, [11] whereas 2% of patients with trigeminal neuralgia have multiple sclerosis. [12] Patients with both conditions often have bilateral trigeminal neuralgia.

Prognosis

After an initial attack, trigeminal neuralgia (TN) may remit for months or even years. Thereafter the attacks may become more frequent, more easily triggered, disabling, and may require long-term medication. Thus, the disease course is typically one of clusters of attacks that wax and wane in frequency. Exacerbations most commonly occur in the fall and spring.

Among the best clinical predictors of a symptomatic form are sensory deficits upon examination and a bilateral distribution of symptoms (but the absence thereof is not a negative predictor). Young age is a moderate predictor, but a fair degree of overlap exists. Lack of therapeutic response and V1 distribution are poor predictors.

Although trigeminal neuralgia is not associated with a shortened life, the morbidity associated with the chronic and recurrent facial pain can be considerable if the condition is not controlled adequately. This condition may evolve into a chronic pain syndrome, and patients may suffer from depression and related loss of daily functioning. Individuals may choose to limit activities that precipitate pain, such as chewing, possibly losing weight in extreme circumstances. In addition, the severity of the pain may lead to suicide.

Patient Education

Patients benefit from an explanation of the natural history of the disorder, including the possibility that the syndrome may remit spontaneously for months or even years before they need to consider long-term anticonvulsant medications. For this reason, some may elect to taper off their medication after the initial attack subsides; thus, they should be educated about the importance of being compliant with their medication regimen.

Patients also must be educated about the potential risks of anticonvulsant medications, such as sedation and ataxia, particularly in elderly patients, which may make driving or operating machinery hazardous. These drugs may also pose risks to the liver and the hematologic system. Document the discussion with the patient about these potential risks.

No specific preventative therapy exists. Patients may have a premonitory atypical pain for months; therefore, appropriate recognition of this pre–trigeminal neuralgia syndrome may lead to earlier and more efficient treatment.

Patients should avoid maneuvers that trigger pain. Once the diagnosis is established, advise them that dental extractions do not afford relief, even if pain radiates into the gums.

In patients wishing to undergo a procedure, they should be aware of potential adverse effects, as well as report any altered sensation in the face, especially after a procedure. They should be informed about the potential for anesthesia dolorosa.

An interactive questionnaire developed by the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Neurological Surgery allows patients to self-diagnose facial pain based on a brief series of questions. The Trigeminal Neuralgia - Diagnostic Questionnaire may be found at: https://neurosurgery.ohsu.edu/tgn.php. An artificial intelligence method (neural network modeling) provides immediate feedback to the patient regarding the diagnosis and patient education resources. [13]

-

Illustration depicting the trigeminal nerve with its 3 main branches

-

Microscopic demonstration of demyelination in primary trigeminal neuralgia. A tortuous axon is surrounded by abnormally discontinuous myelin. (Electron microscope; 3300×).

-

Magnetic resonance image (MRI) with high resolution on the pons demonstrating the trigeminal nerve root. In this case, the patient with trigeminal neuralgia has undergone gamma-knife therapy, and the left-sided treated nerve (arrow) is enhanced by gadolinium.

-

Microvascular decompression (Jannetta procedure) used to treat trigeminal neuralgia. The anteroinferior cerebellar artery and the trigeminal nerve are in direct contact. Courtesy of PT Dang, CH Luxembourg

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Overview of Antiepileptic Drugs

- Carbamazepine Therapy

- Gabapentin Therapy

- Lamotrigine Therapy

- Phenytoin Therapy

- Non-antiepileptic Drug Therapy

- Other Agents

- Surgical Considerations

- Microvascular Decompression

- Percutaneous Procedures

- Gamma Knife Surgery

- Consultations

- Long-Term Monitoring

- Show All

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References