Background

Apraxia of lid opening (ALO) is a nonparalytic motor abnormality “characterized by difficulty initiating the act of lid elevation after lid closure.” [1, 2] Controversy surrounds the designation of this syndrome. Strictly speaking, ALO is not truly an apraxia or “inability to perform a motor action to command despite both an adequate understanding of the action and the elementary ability to carry out.” [3]

Nevertheless, the designation ALO does address the main feature of the condition—namely, the inability to open the eyes at will with preservation of the ability to open them and keep them open at other times. [1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] ALO may present either in isolation or in association with blepharospasm. [1, 10, 11, 12] The challenge for management lies in differentiating these 2 entities.

Pathophysiology

Although the underlying mechanisms of ALO have not been clearly elucidated, it is believed that this condition may involve an abnormality in the supranuclear control of voluntary eyelid elevation, which requires the activation of the levator palpebrae superioris (LPS) and the concurrent inhibition of orbicularis oculi (OO) activity.

Electromyographic studies of the LPS and the OO have demonstrated that the following may cause ALO:

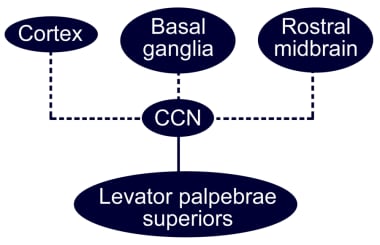

The LPS is innervated bilaterally from the central caudal subdivision of the oculomotor (III) nucleus, and the OO is innervated unilaterally from the facial (VII) nucleus. The cortex, extrapyramidal motor systems, and rostral midbrain structures may control LPS motoneuron activity (see the image below). [18]

Diagram of the possible central pathways involved in the generation of inhibitory responses of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle. Caudal central nucleus (CCN), central caudal subdivision of the oculomotor (III) nucleus.

Diagram of the possible central pathways involved in the generation of inhibitory responses of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle. Caudal central nucleus (CCN), central caudal subdivision of the oculomotor (III) nucleus.

Disturbances in burst, tonic, or pause neurons within any of the aforementioned premotor structures may result in abnormal inhibitor inputs to the LPS motoneurons. Some patients may experience an associated disruption in reciprocal activation of the LPS and the OO.

Etiology

ALO has been attributed to a variety of central nervous system (CNS) lesions in various parts of the brain, including the following [1] :

ALO has been described in association with the following CNS diseases [1] :

-

Progressive supranuclear palsy (one of the most common causes of ALO) [25]

-

Idiopathic dystonias [14]

-

Hydrocephalus [28]

-

Motor neuron disease [29]

-

Dystonia due to kernicterus [13]

-

Choreoathetosis [13]

-

Huntington chorea [2]

-

Shy-Drager syndrome [17]

-

Postencephalitic parkinsonism [17]

-

Neuroacanthocytosis [30]

In addition, the use of the following medications has been reported to induce ALO [2, 17, 25, 31] :

-

Lithium – Lithium intoxication resulted in development of ALO; on withdrawal of lithium, symptoms may remit within 2 weeks [23]

-

Sulpiride – This agent may be associated with ALO; the condition may last approximately 7 months after discontinuation of sulpiride [24]

-

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) – This agent, an analogue of meperidine, has been linked with the induction of parkinsonism associated with ALO [32]

A diagnosis of Wilson disease was made in one patient after he presented with a severe, intermittent inability to open his lids; the original diagnosis was ALO. [33]

Epidemiology

Apraxia of lid opening (ALO) has been reported in 7%, [11] 10%, [10] and 55% [34] of patients with blepharospasm. Benign essential blepharospasm has a prevalence of 12 per million in Japan, [35] 17 per million in Rochester, MN, in the United States, [36] 30 per million in northern England, [37] and 36 per million in the Epidemiologic Study of Dystonia in Europe. [38] The wide variation in these figures may reflect sample bias.

The peak age of onset is in the sixth and seventh decades of life. ALO appears to be more common in women than in men. In a report describing 10 new individuals with ALO and reviewing 11 cases previously mentioned in the literature, Defazio et al found a female-to-male preponderance of 2:1. [39] No racial differences have been reported.

Prognosis

ALO does not directly cause mortality. The morbidity noted in patients with this condition is mostly related to the underlying disease and to the visual impairment in individuals with severe eye closure.

In patients with isolated ALO, the prognosis is excellent. In ALO patients who have other underlying diseases, morbidity or mortality may result as a consequence of the associated condition.

-

Diagram of the possible central pathways involved in the generation of inhibitory responses of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle. Caudal central nucleus (CCN), central caudal subdivision of the oculomotor (III) nucleus.

-

A man with apraxia of lid opening is unable to open his lids at will. Eye movements were full. Attempted eye opening resulted in frontalis muscle contraction, backward thrusting of the head, and pretarsal orbicularis oculi activity. Spontaneous reflex blinking was normal. The lids remained open following manual elevation.