Practice Essentials

Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic, autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering skin disease that rarely involves mucous membranes. Bullous pemphigoid is characterized by the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies specific for the hemidesmosomal bullous pemphigoid antigens (BPAgs) BP230 (BPAg1) and BP180 (BPAg2). Occasionally, sublamina densa deposits are noted, related to anti-p200 antibody. If untreated, bullous pemphigoid can persist for months or years, with periods of spontaneous remissions and exacerbations. It can be fatal, particularly in patients who are debilitated.

Signs and symptoms

Bullous pemphigoid may present with several distinct clinical presentations, as follows:

-

Generalized bullous form - The most common presentation; tense bullae arise on any part of the skin surface, with a predilection for the flexural areas of the skin

-

Vesicular form - Less common than the generalized bullous type; manifests as groups of small, tense blisters, often on an urticarial or erythematous base

-

Vegetative form - Very uncommon, with vegetating plaques in intertriginous areas of the skin, such as the axillae, neck, groin, and inframammary areas

-

Generalized erythroderma form - This rare presentation can resemble psoriasis, generalized atopic dermatitis, or other skin conditions characterized by an exfoliative erythroderma

-

Urticarial form - Some patients with bullous pemphigoid initially present with persistent urticarial lesions that subsequently convert to bullous eruptions; in some patients, urticarial lesions are the sole manifestations of the disease

-

Nodular form - This rare form, termed pemphigoid nodularis, has clinical features that resemble prurigo nodularis, with blisters arising on normal-appearing or nodular lesional skin

-

Acral form - In childhood-onset bullous pemphigoid associated with vaccination, the bullous lesions predominantly affect the palms, soles, and face

-

Infant form - In infants affected by bullous pemphigoid, the blisters tend to occur frequently on the palms, soles, and face, affecting the genital areas rarely; 60% of these infant patients have generalized blisters [1]

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

To establish a diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid, the following tests should be performed:

-

Histopathologic analysis - From the edge of a blister; the histopathologic examination demonstrates a subepidermal blister; the inflammatory infiltrate is typically polymorphous, with an eosinophil predominance; mast cells and basophils may be prominent early in the disease course

-

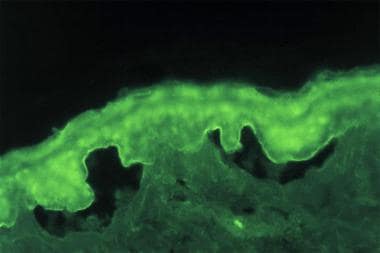

Indirect immunofluorescence (IDIF) studies - Performed on the patient’s serum, if the DIF result is positive (see the second image below)

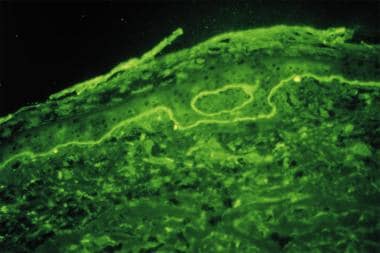

Direct immunofluorescence study performed on perilesional skin biopsy specimen from patient with bullous pemphigoid detects linear band of IgG deposit along dermoepidermal junction.

Direct immunofluorescence study performed on perilesional skin biopsy specimen from patient with bullous pemphigoid detects linear band of IgG deposit along dermoepidermal junction.

Indirect immunofluorescence study performed on salt-split normal human skin substrate with serum from patient with bullous pemphigoid detects IgG-class circulating autoantibodies binding to epidermal (roof) side of skin basement membrane.

Indirect immunofluorescence study performed on salt-split normal human skin substrate with serum from patient with bullous pemphigoid detects IgG-class circulating autoantibodies binding to epidermal (roof) side of skin basement membrane.

DIF tests in patients with bullous pemphigoid usually demonstrate IgG and complement C3 deposition in a linear band at the dermal-epidermal junction, with IgG in salt-split skin found on the blister roof (epidermal side of split skin).

IDIF studies document the presence of circulating IgG autoantibodies in the patient's serum that target the skin basement membrane component. Seventy percent of patients with bullous pemphigoid have circulating autoantibodies that bind to split skin.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

As in other autoimmune bullous diseases, the goal of therapy in bullous pemphigoid is as follows:

-

Decrease blister formation

-

Promote healing of blisters and erosions

-

Determine the minimal dose of medication necessary to control the disease process

The most commonly used medications for bullous pemphigoid are anti-inflammatory agents (eg, corticosteroids, tetracyclines, dapsone) and immunosuppressants (eg, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide). [4, 5] Initial treatment with doxycycline was found to be effective and was associated with a lower incidence of adverse effects as compared with prednisone. [6, 7, 8]

Most patients affected with bullous pemphigoid require therapy for 6-60 months, after which many patients experience long-term remission of the disease. However, some patients have long-standing disease requiring treatment for years.

Most mortality associated with bullous pemphigoid occurs secondary to the effects of medications used in treatment. The population at risk for bullous pemphigoid is at an increased risk for comorbid conditions, [9] such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, [10] and heart disease, [11] which treatment may exacerbate.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Pathophysiology

In patients with bullous pemphigoid, immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies bind to the skin basement membrane. This binding activates complement and inflammatory mediators. Activation of the complement system is thought to play a critical role in attracting inflammatory cells to the basement membrane. These inflammatory cells are postulated to release proteases, which degrade hemidesmosomal proteins and lead to blister formation. On histopathologic analysis, eosinophils are characteristically present in human patients' blisters, though their presence is not an absolute diagnostic criterion.

The precise role of bullous pemphigoid antigens (BPAgs) in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid is not completely clear. BPAg1 (BP230) is an intracellular component of the hemidesmosome; BPAg2 (BP180, type XVII collagen) is a transmembranous protein with a collagenous extracellular domain. [12] Passive transfer experiments in newborn mice demonstrated that rabbit antibodies against mouse BPAg2 can induce subepidermal blisters similar to those observed in patients with bullous pemphigoid. However, the eosinophil infiltration that is frequently observed in human bullous pemphigoid lesional skin was not detected in the passive transfer experimental model. [13]

Another study found that anti-BP180 NC16A domain autoantibodies purified from patients with bullous pemphigoid are capable of inducing dermal-epidermal separation in cryosections of normal human skin. [14]

Studies on autoreactive T and B cells from 35 patients with acute-onset bullous pemphigoid revealed that the percentage of T-cell and B-cell reactivity from these bullous pemphigoid patients against BPAg2 is much higher than that against BPAg1, further suggesting a more prominent role of BPAg2 in disease development. [15]

Serum levels of autoantibodies against BPAg2 have been correlated with disease activity in some studies. [16] Induction of antibodies against BPAg1 in rabbits does not induce primary blistering, but it can enhance the inflammatory response at the basement membrane. The role of autoantibodies specific for BPAgs in the initiation and the perpetuation of disease is unknown.

Although BPAg2 has been identified as the major antigen involved with bullous pemphigoid disease development, autoantibodies against alpha 6 integrin [17] and laminin-5, [18] two other components of skin basement membrane, have been identified in human patients affected by bullous pemphigoid.

No perfect active experimental model has been developed; however, an active animal model was generated in a 2010 study by transferring splenocytes from wild-type mice that had been immunized by grafting human BP180-transgenic mouse skin into Rag-2(–/–)/BP180-humanized mice. [19] The recipient immunodeficient mice developed antihuman BP180 antibodies, manifested with blisters that were consistent with the clinical, histologic, and immunopathologic features of human bullous pemphigoid, except eosinophil infiltration.

In addition, the autoantibody response can be induced in healthy BALB/c mice by immunizing the mice with synthetic peptides of the mouse type XVII collagen NC16A domain, the target region of autoantibodies in human patients affected with bullous pemphigoid. [20]

Eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine, is strongly expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis of lesional bullous pemphigoid skin and parallels the accumulation of eosinophils in the skin basement membrane zone area. It may play a role in the recruitment of eosinophils to the skin basement membrane area.

Other cytokines and chemokines have also been studied in bullous pemphigoid. In a 2004 study, interleukin (IL)-16, a major chemotactic factor responsible for recruiting CD4+ helper T cells to the skin and for inducing functional IL-2 receptors for cellular activation and proliferation, was found to be expressed strongly by epidermal cells and infiltrating CD4+ T cells in lesional bullous pemphigoid skin. [21] Significantly higher levels of IL-16 were detected in sera and blisters of bullous pemphigoid patients as compared with healthy subjects. These findings suggested a role for IL-16 in bullous pemphigoid development.

In a 2006 study, serum levels of monokine induced by interferon gamma (MIG, a Th1-type chemokine) and serum levels of CCL17 and CCL22 (Th2-type chemokines) were significantly increased in bullous pemphigoid patients as compared with healthy subjects. [22]

In another 2006 study, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9, and MMP-13 were found to be significantly increased in lesional bullous pemphigoid skin as compared with that of healthy skin, with T cells accounting for the majority of MMP cellular sources. These findings suggested a role for MMP in the blistering of bullous pemphigoid. [23]

In yet another 2006 study, the cytokine referred to as BAFF (B-cell activating factor, belonging to the tumor necrosis factor [TNF] family), which functions to regulate B-cell proliferation and survival, was found to be significantly increased in sera of bullous pemphigoid patients as compared with healthy subjects, though no significant association was noted between serum BAFF levels and anti-BPAg2 titers. [24]

A 2008 study established a role for the IgE class of autoantibodies, particularly those that target BP180; the higher level of IgE anti-BP180 was correlated with a more severe clinical phenotype. [25]

In a study that used an animal model in which C57BL/6 type of mice engrafted with syngeneic mouse skin transgenically expressed human BPAg2 in the epidermal basement membrane zone, antibodies against the human BPAg2 extracellular domain developed first, followed by antibodies to the intracellular domain of the same human BPAg2. It is noteworthy that the development of later antibodies was associated with the loss of the graft. [26]

IgG autoantibodies from bullous pemphigoid patients have been found to deplete cultured keratinocytes of the BPAg2 and weaken cell attachment in vitro; this further supports their pathogenic role. [27]

The coagulation cascade is activated in bullous pemphigoid patients, and such activation has been found to be correlated with disease severity and with eosinophilia, suggesting a role for eosinophils in this activation of coagulation, which may contribute to the potential thrombotic risk, as well as inflammation, tissue damage, and blister formation. [28]

A 2010 report that described finding anti-BP180 antibodies in unaffected subjects provided suggestive data for further study of the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid. [29]

A 2009 report of bullous pemphigoid that developed after adalimumab treatment for psoriasis raised questions about whether biologics can play a causative role in inducing the disease or whether this development simply reflected an association of bullous pemphigoid with psoriasis. [30]

Bullous pemphigoid has been associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (eg, programmed cell death [PD]-1 inhibitors) used as targeted therapy for malignancy. [31] Some patients developed both pemphigoid and keratoacanthomas. [32, 33, 34]

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors have been associated with a risk of developing bullous pemphigoid. [10, 35, 36, 37]

Environmental factors have been associated with bullous pemphigoid, including daily consumption of the following [38] :

-

Green or herbal tea

-

Fish oil

-

Calcium supplements

-

Multivitamins

-

Glucosamine

Other triggers associated with bullous pemphigoid include use of lime-containg household cleaning products and high levels of mental stress. [38]

Epidemiology

United States and international statistics

Bullous pemphigoid is uncommon, and its precise frequency has not been definitively established.

Bullous pemphigoid has been reported to occur throughout the world. In Europe, bullous pemphigoid has been identified as the most common subepidermal autoimmune blistering disease. In France and Germany, the reported incidence is 6.6 cases per million people per year. In a population-based cohort study from the United Kingdom, the incidence of bullous pemphigoid was found to be 4.3 cases per 100,000 person-years. [39]

Age-, sex-, and race-related demographics

Bullous pemphigoid primarily affects elderly individuals in the fifth through seventh decades of life (average age at onset, 65 y). Bullous pemphigoid of childhood onset has been reported in the literature. It has been suggested that the childhood-onset form may be more self-limited. [40] One puzzling finding, however, is a report of rising incidence of infant-onset bullous pemphigoid.

The incidence of bullous pemphigoid appears to be equal in men and women.

No racial predilection is apparent.

Prognosis

Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic inflammatory disease. If untreated, bullous pemphigoid can persist for months or years, with periods of spontaneous remissions and exacerbations. Most patients affected with bullous pemphigoid require therapy for 6-60 months, after which many experience long-term remission of the disease. Some patients, however, have long-standing disease necessitating treatment for years. The lesions typically heal without scarring or milia formation.

Bullous pemphigoid involves the mucosa in 10-25% of patients. Patients who are affected may have limited oral intake secondary to dysphagia. Erosions secondary to rupture of the blisters may be painful and may limit patients' daily living activities. Blistering on the palms and the soles can severely interfere with patients' daily functions.

Bullous pemphigoid may be fatal, particularly in patients who are debilitated. The proximal causes of death are infection with sepsis and adverse events associated with treatment. Most of the mortality associated with bullous pemphigoid is secondary to the effects of the medications.

In a survey of patients conducted in a United States university medical center, no difference was noted in expected mortality in bullous pemphigoid patients as compared with the general population. [41] In a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom, however, the risk of death for bullous pemphigoid patients was found to be twice as great as that for controls. [39] Furthermore, a Swiss prospective study confirmed a high case-fatality rate, with increased 1-year mortality compared with expected mortality for the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted general population. [42]

Patients with aggressive or widespread disease, those requiring high doses of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, and those with underlying medical problems have increased morbidity (eg, peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, agranulocytosis, and diabetes) and risk of death. Because the average age at the onset of disease is about 65 years, patients with bullous pemphigoid frequently have other comorbid conditions that are common in elderly persons and thus are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants.

The population at risk for bullous pemphigoid is at an increased risk for comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, [10] thromboembolism, and heart diseases, which treatment may exacerbate. [43] Bullous pemphigoid may be linked (directly or indirectly) to neurologic disorders. [9, 44, 45] An increase in the occurrence of neurologic disorders has been reported in patients affected by bullous pemphigoid, relative to the age-matched and sex-matched general population. [46] Further data from studies in different populations will be required to clarify this proposed relation.

Data suggest that high serum levels of IgG1 and IgG4 targeting the noncollagenous 16A domain of BP180 correlate with more serious disease and a worse prognosis. [47] Age and the presence of circulating antibodies are also associated with poor outcome. [48]

In a multicenter, prospective cohort in France, a high titer of anti-BPAg2 autoantibodies by ELISA and a positive direct immunofluorescence (DIF) finding were found to be good indicators of further clinical relapse of bullous pemphigoid and may correlate with overall morbidity and mortality. [49, 50, 51]

Patient Education

Patients should avoid trauma to the skin. Their skin has been rendered fragile by the disease, as well as by the use of topical and systemic steroids. Patients should be educated about their disease and treatments, so that they can report adverse effects to their physicians.

-

Direct immunofluorescence study performed on perilesional skin biopsy specimen from patient with bullous pemphigoid detects linear band of IgG deposit along dermoepidermal junction.

-

Indirect immunofluorescence study performed on salt-split normal human skin substrate with serum from patient with bullous pemphigoid detects IgG-class circulating autoantibodies binding to epidermal (roof) side of skin basement membrane.