Background

Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) is the most common form of cutaneous lesions of lupus associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). [1] It can predict the recurrence of systemic disease or prognosis of the disease in some cases.

Serologic investigations are indicated, along with the clinical picture, to confirm the diagnosis. Sun protection, smoking cessation, and topical therapy are first-line treatment, followed by oral systemic therapy. Additionally, therapies used to treat the systemic disease help in controlling ACLE lesions. Per the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) group, 4 of the 11 clinical criteria used for SLE classification are mucocutaneous in nature and include ACLE (also including subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus [SCLE]), chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), oral or nasal ulcers, and nonscarring alopecia. [2]

Lupus erythematosus is a heterogeneous connective-tissue disease associated with polyclonal B-cell activation and is believed to result from the interplay of genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors. Studies show that B-cell–activating factor (BAFF) is a member of the tumor necrosis receptor superfamily (TNRSF) involved in many immune and inflammatory processes, including SLE. [3] Other immune cells, including T cells, neutrophils, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, have also been shown to play a role in the disease process. The spectrum of disease involvement can vary from limited cutaneous involvement to devastating systemic disease.

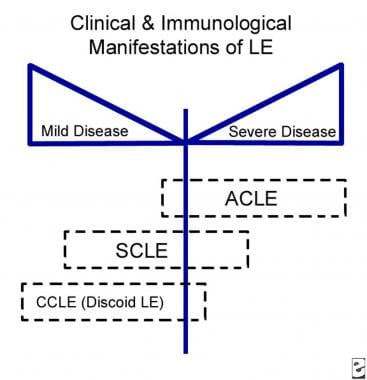

From a dermatologic standpoint, the type of skin involvement can prove to be a good barometer of the pattern of underlying systemic activity. Lupus erythematosus–specific skin diseases are classified into three subsets according to Gilliam and Sontheimer's classification: (1) ACLE, (2) SCLE, and (3) CCLE. See the diagram below. Over the years, intermittent cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ICLE), also known as lupus tumidus, has been introduced as a distinct entity and is included in the Dusseldorf classification by Kuhn and Landmann. [4] Clinical characteristics of each group are unique, although histopathologically, only subtle differences are identified. The major clinical variants of ACLE include localized ACLE, generalized ACLE, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)–like ACLE. The focus of this article is on ACLE. [5, 6]

Relationship of acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) to systemic disease. LE is lupus erythematosus. CCLE is chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. SCLE is subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

Relationship of acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) to systemic disease. LE is lupus erythematosus. CCLE is chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. SCLE is subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

Patients with the localized ACLE present with the classic malar eruption in a "butterfly" pattern localized to the central portion of the face. (See the image below.) Less commonly, patients may present with a generalized maculopapular eruption in photosensitive areas. Rarely, patients may present with TEN-like ACLE featuring vesiculobullous lesions with epidermal sloughing commonly on sun-exposed sites and may involve one or more mucous membranes. [7]

ACLE has a strong association with the systemic disease for which patients present to rheumatologists and internists. Of patients with a new diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 24% have already been diagnosed with SLE and about 18% subsequently are diagnosed with SLE. [8]

Localized ACLE can be transient, lasting for several days to weeks. Lesions wax and wane with sun exposure over a period of several hours; however, some patients experience prolonged disease activity.

Generalized ACLE may present with maculopapular erythema of the hands, specifically over the interphalangeal joints. However, this should be distinguished from Gottron papules of dermatomyositis, which present with an erythematous rash of the metacarpophalangeal joints or knuckles.

TEN-like ACLE presents similarly to Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN (SJS/TEN), which is a severe mucocutaneous skin disease associated with high mortality. SJS/TEN is often triggered by use of certain medications, and, therefore, a careful medication history, clinical evaluation, laboratory investigation, and pathological investigation must be performed to distinguish between the two.

Resolution of lesions in ACLE may result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially in patients with darkly pigmented skin. Usually, the lesions are nonscarring.

Etiology

The etiology of lupus erythematosus is believed to be multifactorial, involving genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors. An association with human leukocyte antigen DR2 and human leukocyte antigen DR3 has been identified. Concordance in monozygotic twins and familial associations support a genetic basis in acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

More than 25 genes have been identified as contributing to the mechanisms that predispose patients to lupus. They include alleles in the major histocompatibility complex region (multiple genes): IRF5, ITGAM, STAT4, BLK, BANK1, PDCD1, PTPN22, TNFSF4, TNFA1P3, SPP1, some fc gene receptors, and deficiency in several complement components, including C1qC4+C2.

In patients who are predisposed genetically, exposure to natural ultraviolet radiation is a frequent precipitating factor for lupus erythematosus. In addition, certain viruses (eg, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) have been implicated in precipitating or exacerbating lupus erythematosus in genetically predisposed individuals.

Smoking has been associated with lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and continued smoking is associated with more severe disease and decreased response to medications. Alcohol consumption has not been reported to affect cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Sex hormones are thought to play a role, as in other female-predominant autoimmune diseases. [9]

Chemicals such as L-canavanine, which is present in alfalfa sprouts, have been known to induce SLE-like illness. Drugs implicated in inducing a lupus erythematosus–like illness (eg, procainamide, isoniazid, hydralazine) typically do not induce ACLE.

Studies have found that microbes can trigger cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Staphylococcus aureus is a common skin pathogen that can colonize the skin following interferon-mediated barrier disruption and is associated with cutaneous lupus erythematosus skin lesions. [10]

See also Bullous Lupus Erythematosus, Discoid Lupus Erythematosus, Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus, and Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus.

Immunopathology

Data concerning direct immunofluorescence in ACLE are sparse. In one study, the results of 5 (100%) of 5 skin biopsy specimens were reported as positive for the lupus band test. The lupus band test reveals the presence of immunoglobulins and C3 complement components along the dermoepidermal junction. All three immunoglobulin classes (IgG, IgM, IgA) and a variety of complement components have been identified at the dermoepidermal junction.

Research has shown that 60% of patients with a malar eruption of lupus erythematosus have positive lupus band test results. In nonlesional skin, positive lupus band test results correlate strongly with an aggressive course of systemic disease.

Histology

Localized and generalized ACLE show histological evidence of interface dermatitis with basal-layer vacuolization with superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper half to the deep dermis and mucin deposits in the reticular dermis. [11] TEN-like ACLE presents histologically with epidermal necrosis with basal vacuolization and necrotic keratinocytes with sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. [12]

Epidemiology

In the United States, the malar rash has been reported in 20-60% of patients in large lupus erythematosus cohorts, while limited data suggest that the maculopapular eruption is present in 35% of patients with SLE. The malar rash is believed to be associated with a younger age of disease onset. The incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Sweden and the United States has been estimated at 4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. [13]

Race-related demographics

Precise data concerning the prevalence of ACLE in specific racial groups are not available; however, since photosensitivity is observed more frequently in White persons than in Black persons, the same prevalence for ACLE may be inferred. Estimates suggest that 1 in 250 Black women in the United States and the Caribbean and 1 in 1000 Chinese persons have SLE.

Although lupus erythematosus may be rare in most parts of Africa, data concerning this finding conflict. A retrospective study in South Africa found that ACLE is more common in non-Black patients with SLE than in Black patients. [14]

Data concerning ACLE are difficult to interpret, since a lack of conformity is found in the description of lesions and biopsy data are lacking for skin lesions observed in patients with systemic disease.

Prognosis

Significant morbidity and potential mortality are associated with SLE, of which ACLE is a manifestation.

The localized malar eruption tends to wax and wane with systemic activity; however, whether the presence of malar rash indicates a worse overall outlook for patients has not yet been determined.

No definite correlation has been identified between ACLE and nephritis; however, localized lesions of ACLE are believed to tend to wax and wane, paralleling the underlying systemic disease. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur in dark-skinned patients following resolution.

Women with SLE who are pregnant and have the Ro/La antibodies should be advised on the risk of developing a fetus with neonatal lupus erythematosus.

Complications

Unlike discoid lupus lesions, lesions of ACLE do not scar with healing. Transient hyperpigmentation is seen during the healing phase. Oral lesions heal without scarring. Very rarely, hypopigmentation can be seen after healing of the malar rash.

-

Relationship of acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) to systemic disease. LE is lupus erythematosus. CCLE is chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. SCLE is subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

-

Erythema involving the malar area, forehead, and neck. Note sparing of some of the creases.

-

Toxic epidermal necrolysis–like eruption.