Background

Nevus of Ota is a dermal melanocytosis originally described by Ota and Tanino in 1939. Clinically, nevus of Ota is distributed along the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve and presents as a blue or gray patch on the face. [1] Around 50% of cases occur at birth, while the remaining occur during puberty and adulthood. Initial hyperpigmentation may present as light in color with continued hyperpigmentation as the individual ages. In addition to the pigmented macule observed on the skin, there have also been rare cases involving ocular and oral mucosal surfaces. [2, 3] See the images below.

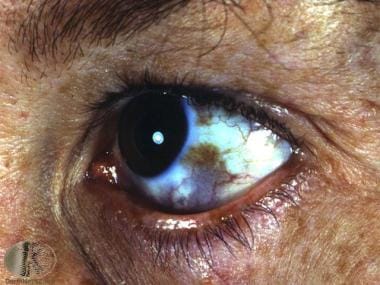

Nevus of Ota. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/ota2.jpg).

Nevus of Ota. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/ota2.jpg).

Nevus of Ota. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/ota.jpg).

Nevus of Ota. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/ota.jpg).

Nevus of Ito, initially described by Minor Ito in 1954, [2, 3, 4] is a similar dermal melanocytic condition like nevus of Ota, differing in distribution. Nevus of Ito is usually found distributed along the posterior supraclavicular and lateral cutaneous brachial nerves of the shoulder. Nevus of Ito often occurs in association with nevus of Ota in the same patient but is much less common, although the true incidence is unknown. From a pathophysiological standpoint, both nevus of Ota and Ito result from failed migration of melanocytes from the neural crest to basal layer of the epidermis. See the image below.

Nevus of Ito. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/melanocytosis-ito.jpg).

Nevus of Ito. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/melanocytosis-ito.jpg).

Additionally, the Medscape article Melanocytic Nevi may be of interest.

Pathophysiology

The etiology and pathogenesis of nevi of Ota and Ito are not known. Although unconfirmed, nevus of Ota and other dermal melanocytic disorders, such as nevus of Ito, blue nevus, and Mongolian spots, may represent melanocytes that have not migrated completely from the neural crest to the epidermis during the embryonic stage. [5] The variable prevalence among different populations suggests genetic influences, although familial cases of nevus of Ota are exceedingly rare. The two peak ages of onset in early infancy and in early adolescence suggest that hormones are a factor in the development of these conditions. Schwann cell precursors have been shown to be a source of melanocytes in skin. [6] The observation of dermal melanocytes in close proximity with peripheral nerve bundles in nevus of Ito suggests that the nervous system is a factor in the development of nevus of Ito, although the true pathogenesis remains unknown.

One theory regarding the pathogenesis of nevi of Ota and Ito. It has been demonstrated that most nevi and melanomas are associated with mutations in the BRAF and NRAS genes of the MAP kinase pathway. [7, 8] However, blue nevi and nevi of Ota and Ito do not possess these mutations. Instead, it has been discovered that the melanocytes present in these lesions often contain a mutation in a G-coupled protein gene, GNAQ. This mutation causes the G-coupled protein to be constitutively turned on, resulting in increases in the melanoblast pool. These melanoblasts then migrate during embryogenesis to the skin, the uvea, and/or the meninges, creating the various manifestations of Nevus of Ota. [9, 10, 11] This would explain the association between nevus of Ota and uveal and leptomeningeal melanocytosies. GNAQ mutations have also been shown to underlie other cutaneous disorders, including phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (of which melanocytosis may be a feature), [12] nevus flammeus, [13] and Sturge-Weber syndrome.

It has also been shown that the risk of developing cutaneous, uveal, or leptomeningeal melanomas in the setting of lesions such as nevus of Ota is related to monosomy of chromosome 3. The tumor suppressor gene BAP1 (BRCA-associated protein 1) is located on this chromosome. Loss of one the BAP1 allele is linked with an adverse prognosis. Monosomy 3, coupled with loss of 1q or gain of 8q, is associated with a worse outcome. Evaluation for this abnormality in melanomas associated with nevus of Ota could aid in prognosis, treatment, and follow-up. [14]

Epidemiology

Race

Nevi of Ota and Ito occur most frequently in individuals of Asian descent, with an estimated prevalence of 0.2-0.6% for nevus of Ota in the Japanese population. Nevus of Ito is less common than nevus of Ota, although the true incidence is unknown.

Studies have shown prevalence in other ethnic groups including Africans, African Americans, and East Indians.

Nevi of Ota and Ito are uncommon in whites.

Sex

Females are shown to be affected five times more than males, with the male-to-female ratio is 1:5 for nevus of Ota. [15] The ratio for nevus of Ito is unknown.

Age

The initial presentation of both nevus of Ota and Ito occurs in infancy, with as many as 50% of nevus of Ota cases present at birth.

Nevus of Ota may also present itself during adolescence.

Additionally, there have been rare cases of delayed-onset nevi of Ota that first appear in adults, including in older patients. [16, 17]

Prognosis

Lesions may display progressive hyperpigmentation with age, and, without treatment, lesions remain permanent.

It is important to note the psychosocial impact that Nevus of Ota can have on those affected, as disease progression can cause facial disfigurement. [18] In rare cases, melanoma, which can be life threatening, has been reported to arise from nevus of Ota. [19] Glaucoma also has been associated with nevus of Ota. Recurrence may also occur with incomplete removal of lesions.

Nevus of Ito usually does not have symptoms and causes little cosmetic concern to patients; sensory changes occasionally are present in the lesion. Rarely, nevus of Ito has progressed to cutaneous melanoma. [19, 20]

Patient Education

It is important that patients be made aware of the risk associated with the development of glaucoma as this may progress to vision loss. Periodic follow-up visits with an ophthalmologist should be encouraged.

Despite there being a rare risk of transformation into malignant melanoma, patients should be encouraged to report any changes in size and/or color to the lesional areas.

-

Nevus of Ota. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/ota2.jpg).

-

Nevus of Ota. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/ota.jpg).

-

Nevus of Ito. Courtesy of DermNet New Zealand (https://www.dermnetnz.org/assets/Uploads/lesions/melanocytosis-ito.jpg).