Practice Essentials

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) is the third or late stage of European Lyme borreliosis. [1, 2] This unusual progressive fibrosing skin process is caused by an ongoing active infection with Borrelia afzelii. First delineated in 1883, [3] it was described in 1902 as a tissue paper–like cutaneous atrophy. [4] See the image below.

A 73-year-old female farmer with a cutaneous plaque on the sole of her right foot lasting for 6 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto the dorsum of her foot, her right leg, and the lower part of her right thigh. Infection of Borrelia burgdorferi was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically.

A 73-year-old female farmer with a cutaneous plaque on the sole of her right foot lasting for 6 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto the dorsum of her foot, her right leg, and the lower part of her right thigh. Infection of Borrelia burgdorferi was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically.

ACA is evident on the extremities, particularly on the extensor surfaces. It begins with an inflammatory stage characterized by bluish red discoloration and cutaneous swelling and concludes several months or years later with an atrophic phase. Sclerotic skin plaques may also develop. Physicians should use serologic and histologic examination to confirm this diagnosis.

The choice of treatment for ACA depends on the coexistence of other signs or symptoms of Lyme borreliosis. Appropriate consultations (ie, a neurologist, ophthalmologist, rheumatologist, or cardiologist) should be sought if extracutaneous signs and symptoms are present. ACA patients without concurrent extracutaneous disease do not require hospitalization.

Signs and symptoms

Also see History.

Clinical recognition of ACA may be difficult, even in typical cases. A detailed history, including epidemiologic data, is helpful. Physicians should confirm the clinical diagnosis by means of histopathologic examination and serologic testing.

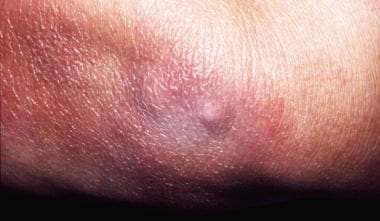

The early, inflammatory phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is marked by soft, painless, poorly demarcated, bluish red plaques that tend to coalesce or by diffuse erythema and edema localized on the distal extremities that spread proximally (see the images below).

A 73-year-old female farmer with a cutaneous plaque on the sole of her right foot lasting for 6 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto the dorsum of her foot, her right leg, and the lower part of her right thigh. Infection of Borrelia burgdorferi was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically.

A 73-year-old female farmer with a cutaneous plaque on the sole of her right foot lasting for 6 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto the dorsum of her foot, her right leg, and the lower part of her right thigh. Infection of Borrelia burgdorferi was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically.

A 50-year-old male farmer was examined for cutaneous plaques on the dorsal side of his right hand lasting for 8 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto his right forearm and arm and had also developed on his right thigh. The patient complained of muscular weakness related to his right upper limb and periodic arthralgia. The neurologic examination demonstrated signs of right brachial plexus damage, confirmed by electromyography. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect immunofluorescence assay (titer: 1:1,024), and Western blot. Histologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.

A 50-year-old male farmer was examined for cutaneous plaques on the dorsal side of his right hand lasting for 8 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto his right forearm and arm and had also developed on his right thigh. The patient complained of muscular weakness related to his right upper limb and periodic arthralgia. The neurologic examination demonstrated signs of right brachial plexus damage, confirmed by electromyography. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect immunofluorescence assay (titer: 1:1,024), and Western blot. Histologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.

A 68-year-old woman with a history of untreated erythema migrans on her left thigh 2 years previously. Ten months later, the plaque extended over the skin of her left buttock and became bluish with signs of livedo racemosa. Her forearms and breast were also involved. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:4,096) and Western blot. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically. Because of intrathecal production of specific antibodies, diagnosis of asymptomatic neuroborreliosis was established.

A 68-year-old woman with a history of untreated erythema migrans on her left thigh 2 years previously. Ten months later, the plaque extended over the skin of her left buttock and became bluish with signs of livedo racemosa. Her forearms and breast were also involved. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:4,096) and Western blot. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically. Because of intrathecal production of specific antibodies, diagnosis of asymptomatic neuroborreliosis was established.

In the authors’ experience, not only the distal extremities but also the proximal parts, the trunk, and the face may be involved in the early stage of ACA. Others have also observed skin-colored facial edema as an initial manifestation of ACA (see the images below). [5] Skin changes are often associated with regional or generalized lymphadenopathy.

A 69-year-old woman. The initial lesion developed on the dorsal side of her left hand 2 years previously and extended onto her left forearm and arm. A new erythematous lesion developed 2 months before on her right cheek beside the rosacea signs. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed in the biopsy specimen taken from the skin of the forearm, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:2,048). The atrophic phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is visible on the hand, and the inflammatory phase is visible on the cheek.

A 69-year-old woman. The initial lesion developed on the dorsal side of her left hand 2 years previously and extended onto her left forearm and arm. A new erythematous lesion developed 2 months before on her right cheek beside the rosacea signs. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed in the biopsy specimen taken from the skin of the forearm, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:2,048). The atrophic phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is visible on the hand, and the inflammatory phase is visible on the cheek.

The inflammatory phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans can be seen with rosacea lesions on the cheek, the forehead, and the nose.

The inflammatory phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans can be seen with rosacea lesions on the cheek, the forehead, and the nose.

The later, atrophic phase of ACA is more characteristic clinically (see the images below). The affected skin exhibits the following:

-

Dark red or brownish red discoloration

-

Focal hyperpigmentation

-

Telangiectasias

Because of the loss of subcutaneous fat, the skin vessels become prominent. Atrophy of the epidermis and lack of hairs, sebaceous glands, and often sweat glands make the skin poorly protected and vulnerable. Large ulcerations can be observed, and malignant lesions may also occur. The atrophic poikilodermic changes are often bilateral and most noticeable over the knees, the elbows, and the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the feet. They may also involve the trunk (particularly the chest) and the face. Note the image below.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of frequent tick bites and an initial inflammatory skin lesion on the left medial part of her ankle 2 years previously. The lesion extended onto the left leg and involved the knee. Fibrotic nodules developed in the medial part of the ankle and the knee. Moreover, she complained of balance disturbances and vertigo. Neurologic examination revealed the asymmetry of profound reflexes, bilateral lack of plantar reflexes with a tendency to the extensor plantar response (Babinski sign), ataxia, profound dysesthesia, and muscular atrophy of the left calf. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed by histologic examination, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection was confirmed by a high specific antibody titer with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:8,192); cerebrospinal fluid was not tested.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of frequent tick bites and an initial inflammatory skin lesion on the left medial part of her ankle 2 years previously. The lesion extended onto the left leg and involved the knee. Fibrotic nodules developed in the medial part of the ankle and the knee. Moreover, she complained of balance disturbances and vertigo. Neurologic examination revealed the asymmetry of profound reflexes, bilateral lack of plantar reflexes with a tendency to the extensor plantar response (Babinski sign), ataxia, profound dysesthesia, and muscular atrophy of the left calf. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed by histologic examination, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection was confirmed by a high specific antibody titer with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:8,192); cerebrospinal fluid was not tested.

Sclerodermalike changes may appear in both the inflammatory phase and the atrophic phase of ACA. These changes are usually limited to the legs and the feet, but they occasionally occur on the trunk. The lesions, similar to morphea and lichen sclerosus and atrophicus, may appear in regions where no ACA is present. ACA may be evident as an asymmetric red-blue hypertrophic hand and tenosynovitis. [6]

Single or multiple fibrotic nodules or bands may be seen on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and the knees or adjacent to other joints (see the image below). They are generally firm; bluish red, yellowish, or skin-colored; and 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter.

ACA has been described in association with localized amyloidosis, eczema, psoriasis, lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and Hodgkin disease; however, these associations may be coincidental. One of the authors’ patients with histologically and serologically confirmed ACA was a 68-year-old woman first seen with prominent livedo racemosa on the leg where typical ACA inflammatory-phase patches developed. [7] Others observed the same phenomenon; thus, this may be more than a chance linkage.

Detailed clinical and neurophysiologic examinations in patients with ACA-associated polyneuropathy often show a sensory polyneuropathy. Neuropathy symptoms (typically pain, paresthesia or both) are evident in one half of patients with ACA. One of the authors’ patients had paresis of the brachial plexus. [7] Marked abnormality of the vibratory threshold is a common finding.

Patients with localized or asymmetric neuropathy seem to have changes more often found in the extremities with, rather than without, visible acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans lesions. Abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid seldom have been found in patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.

ACA can produce deformities of the fingers and the toes if it is not treated promptly. Persistent reducible deformities of the fingers may be consistent with Jaccoud arthropathy.

ACA flared after antiretroviral treatment in an HIV-infected patient, a pattern not yet widely recognized. [8]

Diagnostics

See Workup.

Management

Also see Long-term monitoring and Medication.

Approach considerations

The choice of treatment for acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) depends on the coexistence of other signs or symptoms of Lyme borreliosis. One should also take into account the results of serologic tests. If not treated early, ACA can be associated with joint manifestations and persistent finger deformities.

Appropriate consultations (ie, neurologist, ophthalmologist, rheumatologist, cardiologist) should be sought if extracutaneous signs and symptoms are present. ACA patients without concurrent extracutaneous disease do not require hospitalization.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a vaccine against Lyme borreliosis for distribution in the United States in January 1999, but it is not currently in general use. At present, for European countries, a recombined vaccine is being prepared from the surface lipoprotein A (OspA) made from prevalent strains of B afzelii and B garinii.

Pharmacologic therapy

If extracutaneous Lyme borreliosis signs are absent and the level of specific antibodies is low, the authors usually recommend oral doxycycline or oral amoxicillin administered over a period of 3 weeks.

If organic or systemic physical or laboratory signs of Lyme borreliosis are present or if the antibody titer is high, appropriate treatment should be initiated, typically with ceftriaxone or cefotaxime or aqueous penicillin G given intravenously (IV) for 21-28 days. In a 2018 study, 5 of 7 patients had acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans resolve completely with ceftriaxone therapy. [9]

The possibility of another concurrent infection (eg, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, or tick-borne encephalitis) must be kept in mind. About 10% of patients with Lyme disease in southern New England are coinfected with babesiosis, and about the same percentage in parts of the Midwestern United States have human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE). Unlike ehrlichiosis, which is usually a short-lived infection, babesiosis can be persistent and may coexist with ACA.

Patients in the early phase of ACA should be assured that resolution of symptoms may occur gradually over a period of several weeks or months after treatment (see the images below); patients treated in the atrophic phase should be informed that although disease progression can be stopped, the symptoms may be only partially reversible.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

B afzelii is the predominant etiologic agent of ACA but may not be the sole cause. Borrelia garinii, another genospecies of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (“in the broad sense”) complex, has also been detected in this setting.

ACA is the only form of Lyme borreliosis in which no spontaneous remission occurs. Its pathophysiology is not yet fully understood. ACA appears to be associated with long-term persistence of Borrelia organisms in the skin; several nonspecific reactions, together with a specific immune response, may contribute to its manifestations.

The persistence of the spirochetes despite a marked cutaneous T-cell infiltration and high serum antibody titers may be connected with the following factors:

-

Resistance of the pathogen to the complement system

-

The pathogen’s ability to escape to immunologically protected sites (eg, endothelial cells, fibroblasts)

-

The pathogen’s ability to change antigens, which may lead to an inappropriate immune response

Lack of protective antibodies, with a narrow antibody spectrum and a weak cellular response characterized by downregulation of major histocompatibility system (MHC) class II molecules on Langerhans cells, has been observed in patients with Lyme borreliosis.

A restricted pattern of cytokine expression in ACA, including lack of interferon gamma, may contribute to its chronicity. Cross-reactive antibody responses could take part in autoimmune damage, but whether autoimmune reactions play any role in the pathogenesis of the disease is unclear. The pathogenic mechanism of atrophic skin changes also has not been clarified. Perhaps periarticular regions are favored sites because of reduced acral skin temperatures or reduced oxygen pressure.

Lack of adequate or appropriate treatment of early Lyme borreliosis facilitates the development of ACA.

Epidemiology

The occurrence of ACA is connected with the ecology of Lyme borreliosis, which varies in different geographical regions of the world.

United States statistics

Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus, and 4 other tick species distributed in North America transmit B burgdorferi sensu stricto (“in the strict sense”), causing erythema migrans and Lyme borreliosis arthritis.

Despite a high incidence of Lyme borreliosis in the United States (ranging from 95 cases per 100,000 population in Connecticut to 1250 cases per 100,000 population in Nantucket County, MA [1996 data]), ACA is not seen in the United States, except in a few European immigrants. [10]

International statistics

The tick vectors of B afzelii, the main etiologic agent of ACA (and erythema migrans), are Ixodes ricinus, Ixodes hexagonus, and Ixodes persulcatus, which are distributed in western and central Europe and in far eastern Europe and Asia. Almost all of these hard tick species may also transmit B garinii, a causative agent of erythema migrans and neurologic symptoms of Lyme borreliosis.

In Europe, Lyme borreliosis with all its dermatologic manifestations occurs in almost all countries, predominantly in the central part of the continent. The annual incidence ranges from 16 cases per 100,000 population in France to 120 cases per 100,000 population in northeastern Poland and Slovenia and to 130 cases per 100,000 population in Austria (1995 data). [11] In Germany, it has an incidence of up to 138 cases per 100, 000 population. [12]

The overall prevalence of ACA in all European patients with Lyme borreliosis is about 1-10%, depending on the region of the population sampled. Among the group of patients with skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis observed in Vienna, the ratio of erythema migrans cases to ACA cases and to Borrelia lymphocytoma (BL) cases was 30:3:1. In the authors’ as-yet-unpublished studies (involving a group of patients with Lyme borreliosis in northeastern Poland), this ratio is 170:5:1.

Because the clinical diagnosis of ACA is much more difficult than that of erythema migrans or BL, the condition is often underdiagnosed; in fact, the ratio of erythema migrans cases to ACA cases may be higher than those already cited. The total number of cases could increase with the frequency of untreated European Lyme borreliosis rises. ACA is probably the most common late and chronic manifestation of the borreliosis seen in European patients with Lyme disease.

A Bulgarian survey found that both BL and ACA were rare (0.3%). [13]

Of over 700 patients from an endemic region of northern Italy, erythema migrans was noted in more than half, with 7 having lymphadenosis benigna cutis and 18 ACA. [14]

Age-related demographics

ACA can occur in any age group but it is most common in adults, mainly those in their 40s or 50s. The youngest of the authors’ patients was 26 years of age; the oldest was 73 years. [7] The mean age of the female group was 54.3 ± 12.8 years; the mean age of the male group was 46.2 ± 6.5 years. ACA is rare in adolescents; however, it has been observed in children. A case in a 15-year-old girl was reported by Zalaudek et al in 2005. [15]

Sex-related demographics

More than two thirds of patients with ACA are women. Of the authors’ 19 patients, only 5 were men. [7] A Slovenian study of 693 patients delineated 461 females and 232 males, with a median age of 64 years, [16] concluding that ACA usually affects older women.

Race-related demographics

ACA is not limited to any nationality or race. In general, however, it is much more frequent in whites than in persons of other races, probably because of a far higher exposure to ticks transmitting B afzelii.

Prognosis

The course of ACA is prolonged and may extend for as long as several years. It leads to extensive flaccid atrophy of the skin and, in some patients, to limitation of upper and lower limb joint mobility. Chronic, difficult-to-treat ulcerations of atrophic skin may develop after minor trauma. Bacterial superinfections may be seen.

The general status of patients with ACA remains good, though they may experience neurologic or rheumatologic signs and symptoms. As a rule, the outcome of treatment is good if the acute inflammatory stage of ACA is treated adequately. The therapeutic outcome is difficult to assess in patients with the chronic atrophic phase, in which many changes are only partially reversible.

Although ACA rarely occurs in childhood, its prognosis in pediatric patients is uncertain. For this reason, it should be treated as early as possible to prevent irreversible cutaneous damage. [17]

Rarely, a B-cell lymphoma may develop in these patients, as may a basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. [18] A metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma was described in a patient with long-standing ACA. On the whole, however, malignant degeneration has been quite uncommon; accordingly, ACA should not be considered a precancerous disorder.

Patient Education

Patients and their families should receive information about how to lower the risk of acquiring ACA. Persons residing in endemic areas should examine their bodies for ticks every 12 hours and should expeditiously remove any attached ticks. To discourage ticks from accessing exposed skin, they should use personal protection (eg, light-colored clothing to facilitate tick visualization) and tuck their pants cuffs into socks.

Also see Tick Removal.

-

The most common localization of the skin lesions in 12 patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA). The number of ACA lesions in the particular body region is shown.

-

A 73-year-old female farmer with a cutaneous plaque on the sole of her right foot lasting for 6 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto the dorsum of her foot, her right leg, and the lower part of her right thigh. Infection of Borrelia burgdorferi was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically.

-

The external part of the right foot.

-

A 50-year-old male farmer was examined for cutaneous plaques on the dorsal side of his right hand lasting for 8 months that, in the meantime, had extended onto his right forearm and arm and had also developed on his right thigh. The patient complained of muscular weakness related to his right upper limb and periodic arthralgia. The neurologic examination demonstrated signs of right brachial plexus damage, confirmed by electromyography. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect immunofluorescence assay (titer: 1:1,024), and Western blot. Histologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.

-

The typical inflammatory phase patches are seen on the right hand bone prominences.

-

A 68-year-old woman with a history of untreated erythema migrans on her left thigh 2 years previously. Ten months later, the plaque extended over the skin of her left buttock and became bluish with signs of livedo racemosa. Her forearms and breast were also involved. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:4,096) and Western blot. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed histologically. Because of intrathecal production of specific antibodies, diagnosis of asymptomatic neuroborreliosis was established.

-

After 30 days of treatment with ceftriaxone.

-

The livedo racemosa and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans lesions on the left thigh and buttock before treatment.

-

The same patient after treatment.

-

A 69-year-old woman. The initial lesion developed on the dorsal side of her left hand 2 years previously and extended onto her left forearm and arm. A new erythematous lesion developed 2 months before on her right cheek beside the rosacea signs. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed in the biopsy specimen taken from the skin of the forearm, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:2,048). The atrophic phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is visible on the hand, and the inflammatory phase is visible on the cheek.

-

The inflammatory phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans can be seen with rosacea lesions on the cheek, the forehead, and the nose.

-

Fibrotic nodules on the left elbow.

-

A 48-year-old woman with a history of frequent tick bites and an initial inflammatory skin lesion on the left medial part of her ankle 2 years previously. The lesion extended onto the left leg and involved the knee. Fibrotic nodules developed in the medial part of the ankle and the knee. Moreover, she complained of balance disturbances and vertigo. Neurologic examination revealed the asymmetry of profound reflexes, bilateral lack of plantar reflexes with a tendency to the extensor plantar response (Babinski sign), ataxia, profound dysesthesia, and muscular atrophy of the left calf. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was confirmed by histologic examination, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection was confirmed by a high specific antibody titer with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:8,192); cerebrospinal fluid was not tested.

-

A 26-year-old female nurse recalled the onset of the disease on her right arm 4 years before. After 6 months, the plaques extended onto the right forearm and hand. The left arm and forearm were also involved 3 years previously. Induration of the skin of the right forearm was noted. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was diagnosed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:2,048) and confirmed by positive Western blot for both immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G antibodies.

-

Atrophic phase of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans of the right upper limb with induration of the forearm.

-

A 68-year-old female jogger frequently exposed to ticks. Cutaneous plaques developed 4 years previously on her right lower limb and the right part of her trunk, including her breast and right upper limb. Typical extensive cigarette paper–like plaques, bluish or brownish red in color were evident. Fibrous nodules were found on her right elbow. Borrelia burgdorferi infection was confirmed with indirect immunofluorescence assay (1:1,024) and Western blot. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans was finally diagnosed by using histologic examinations.

-

A widespread acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans atrophic plaque on the back.

-

The atrophic skin lesions and fibrotic nodules of the right upper limb.

-

Biopsy specimen from the wrist of the patient shown in Image 4. The epidermis is slightly flattened. A zone of normal connective tissue can be seen below the epidermis. A patchy infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells is seen throughout the dermis. Telangiectasias are evident in the upper and deeper parts of the dermis.

-

A higher magnification. Telangiectatic vessels are surrounded by a cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis.

-

A higher magnification of the same biopsy specimen. Note the patchy cell infiltrate around the large vessels in the deep dermis.