Practice Essentials

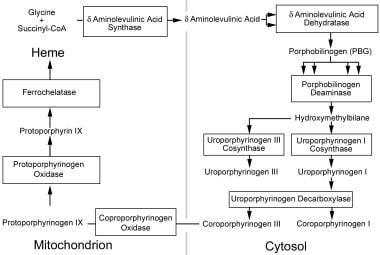

The porphyrias are caused by enzyme deficiencies in the heme production pathway. [1, 2] Such deficiencies may be due to inborn errors of metabolism or exposure to environmental toxins or infectious agents. Because of the ubiquitous use of heme in the human body, severe enzyme deficiencies are lethal. See the image below.

Heme production pathway. Heme production begins in the mitochondria, proceeds into the cytoplasm, and resumes in the mitochondria for the final steps. Figure outlines the enzymes and intermediates involved in the porphyrias. Names of enzymes are presented in the boxes; names of the intermediates, outside the boxes. Multiple arrows leading to a box demonstrate that multiple intermediates are required as substrates for the enzyme to produce 1 product.

Heme production pathway. Heme production begins in the mitochondria, proceeds into the cytoplasm, and resumes in the mitochondria for the final steps. Figure outlines the enzymes and intermediates involved in the porphyrias. Names of enzymes are presented in the boxes; names of the intermediates, outside the boxes. Multiple arrows leading to a box demonstrate that multiple intermediates are required as substrates for the enzyme to produce 1 product.

Signs and symptoms of acute porphyria

Vital sign symptoms include the following:

-

High blood pressure and tachycardia during acute attacks

-

Chronic changes (eg, sustained hypertension in 20% of patients)

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms include the following:

-

Abdominal pain

-

Nausea, vomiting

-

Partial ileus with accompanying severe nonfocal abdominal pain

-

Absent peritoneal signs

Autonomic neuropathy symptoms include the following [3] :

-

Unstable vital signs

-

Excessive sweating

-

Dysuria and bladder dysfunction

-

Fever

-

Restlessness

-

Tremor

-

Catecholamine hypersecretion

Peripheral neuropathy symptoms include the following:

-

Guillain-Barré–like syndrome after prolonged and severe episodes

-

Focal, asymmetrical, or symmetrical weakness beginning proximally and spreading distally with foot or wrist drop

-

Focal, patchy mild-to-severe paresthesias, numbness, and dysesthesias

-

Tetraplegia (reported in cases of hereditary coproporphyria [HCP])

-

Respiratory paralysis (rare, but can occur)

Cranial nerve symptoms include the following:

-

Motor nerve palsies (particularly cranial nerves VII and X)

-

Optic nerve involvement (may lead to blindness)

Seizure symptoms include the following:

-

Seizures are most common during acute attacks

-

Tonic-clonic

Background

Many genetic defects result in porphyria. Variable penetrance is the rule. In most cases, concomitant environmental and genetic factors are required to produce phenotypic symptoms, though the exact nature of such factors is unknown.

Porphyrias are divided into acute and cutaneous categories based on their predominant symptoms. Patients with acute porphyrias (ie, neurovisceral porphyria) present with symptoms of abdominal pain, neuropathy, autonomic instability, and psychosis. Cutaneous porphyrias cause photosensitive lesions on the skin. Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) deficiency and acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) cause predominately neurovisceral symptoms, whereas congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP), porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), and erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) mainly cause cutaneous symptoms. Hereditary coproporphyria (HCP) and variegate porphyria (VP) cause both acute and cutaneous symptoms.

This article addresses only the acute porphyrias. For information on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous porphyrias and cutaneous manifestations of porphyrias with neurovisceral and cutaneous components, see Porphyria, Cutaneous. This division is aimed at presenting these disorders in an easily understandable format.

Some of the confusion regarding the porphyrias is derived from the many synonyms for each particular disorder.

Synonyms associated with the various types of acute porphyria are as follows:

Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase

See the list below:

-

ALAD Deficiency

-

Porphobilinogen (PBG) synthase deficiency

-

Aminolevulinic acid (ALA) dehydrase deficiency

-

ALA-uria

-

Doss porphyria

Acute intermittent porphyria

See the list below:

-

Intermittent acute porphyria

-

Waldenstrom porphyria

-

Pyrroloporphyria

Hereditary coproporphyria

See the list below:

-

Coproporphyria

-

Coproporphyrinogen oxidase deficiency

Variegate porphyria

See the list below:

-

Protoporphyrinogen oxidase deficiency

-

South African porphyria

-

Porphyria variegata

-

Protocoproporphyria hereditaria

Pathophysiology

Porphyrin pathway

Heme is an essential physiologic compound. It is critical for oxygen binding and transport, for the cytochrome P-450 pathway, for activation and decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, for oxidation of tryptophan and prostaglandins, and for the production of cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP). The liver produces approximately 15% of the body's heme; bone marrow produces the remainder. Heme produced in the liver is primarily used for cytochromes and peroxisomes, whereas heme produced in the bone marrow is used primarily for oxygen transport. Biosynthesis of 1 heme molecule requires 8 molecules of glycine and succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA). [6]

Enzymes required for the biosynthesis of heme are located in the mitochondria or the cytosol.

Table 1. Known Chromosomal Location of Enzymes Involved in Porphyria and Inheritance Patterns (Open Table in a new window)

Type of Porphyria |

Deficient Enzyme |

Location |

Inheritance Pattern |

Band |

|

ALAD deficiency |

ALAD |

Cytosol |

Autosomal recessive |

9q34 |

|

AIP |

PBG deaminase |

Cytosol |

Autosomal dominant |

11q23 |

|

HCP |

Coproporphyrinogen oxidase |

Mitochondrial |

Autosomal dominant |

3q12 |

|

VP |

Protoporphyrinogen oxidase |

Mitochondrial |

Autosomal dominant |

1q22-23 |

|

As the first step in the heme biosynthesis pathway, ALA synthase condenses glycine and succinyl-CoA. This enzyme has 2 isoforms encoded by separate genes; all tissues express the housekeeping isoform, whereas only hematologic tissue express the erythroid isoform. ALA synthase is the rate-limiting step for heme production in the liver but not in the bone marrow. The erythron responds to stimuli for heme synthesis by increasing cell number. In the liver, ALA synthase and PBG deaminase are normally at low levels, resulting in ALA and PBG accumulation with increased ALA production under normal conditions. High ALA levels induce heme oxygenase, increase bilirubin production, and inhibit ALA synthase.

Heme inhibits ALA synthase synthesis, mitochondrial transfer, and catalytic activity. These inhibitory mechanisms lead to tight control of ALA production since ALA synthase turnover is rapid. Exogenous chemicals can induce ALA synthase in the liver by depleting existing heme or by inhibiting heme synthesis. The 3 common mechanisms are destruction or enhanced production of cytochrome P-450 heme and rapid inhibition of ferrochelatase.

ALAD condenses 2 molecules of ALA to form the monopyrrole PBG. ALAD is inhibited by lead, levulinic acid, hemin, succinylacetone, and alcohol. Lead displaces zinc from the enzyme, but this inhibition can be reversed by administering supplemental zinc or dithiothreitol. Succinylacetone, a substrate analogue of ALA found in patients with hereditary tyrosinemia, is the most potent inhibitor of ALAD.

PBG deaminase catalyzes the polymerization of 4 molecules of PBG, in a head-to-tail orientation, yielding a linear tetrapyrrole intermediate hydroxymethylbilane. The same structural gene encodes tissue and erythrocyte isoenzymes.

Uroporphyrinogen I and III cosynthase form uroporphyrinogen I and III from hydroxymethylbilane cyclizing the linear molecule. Uroporphyrinogen I reverses the orientation of the last pyrrole ring while uroporphyrinogen I does not. Normal tissues contain an excess of uroporphyrinogen cosynthases, compared with PBG deaminase.

Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase sequentially removes a carboxylic group from the acetic side chains of each of the pyrrole rings to yield coproporphyrinogen. This enzyme has highest affinity for uroporphyrinogen III. Several metals (eg, copper, mercury, platinum) inhibit this enzyme. The effect of iron on this enzyme is not clear.

Coproporphyrinogen oxidase removes a carboxyl group from the propionic groups on 2 of the pyrrole rings to yield protoporphyrinogen IX. Protoporphyrinogen oxidase forms protoporphyrin IX by removing 6 hydrogen atoms from protoporphyrinogen IX. This enzyme has been identified in human fibroblasts, erythrocytes, and leukocytes and is noncompetitively and irreversibly inhibited by hemin. Iron is inserted into protoporphyrin by ferrochelatase as the final step in the heme synthesis pathway. Enzyme activity is stimulated by fatty acids and is inhibited by metals (eg, cobalt, zinc, lead, copper, manganese) and by metalloporphyrins.

Nervous system dysfunction

ALA, PBG, and their derivatives are neurotoxic to central and peripheral nerves. Disturbed heme synthesis in neural tissue results in depletion of essential cofactors and substrates. For example, Schwann cells may be sensitive to damage because they synthesize and use cytochrome P-450. Any disturbance in cytochrome production and function may lead to cell dysfunction and demyelination.

ALA antagonizes the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor and may cause oxidative damage to nervous tissue. Decreased activity of the heme-dependent protein tryptophan pyrrolase in the liver supposedly increases central and systemic tryptophan levels due to decreased tryptophan degradation. Increased central 5-hydroxytryptamine levels may cause cognitive changes.

Chronic renal failure

Chronic renal failure may be caused by a combination of sustained hypertension, analgesic nephropathy, and intermediates in the nephrotoxic porphyrin pathway.

DNA damage

ALA may cause dose-dependent damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

The absence of a porphyria registry in the United States impedes accurate calculation of disease frequency. Incidence of the acute porphyrias varies with type (see Table 2). The highly variable phenotypic expression results in a highly variable penetrance. Most individuals with the genetic defects are asymptomatic. Therefore, underdiagnosis and variable penetrance contribute to the lack of knowledge about the incidence of acute porphyria.

The proportion of patients with a known PBG deaminase mutation who develop symptoms appears to have decreased substantially after 1980.

International

The frequency of the genetic defects that cause porphyria is unknown. Surveillance studies aimed at symptomatic families may bias genetic defect prevalence. Incidences listed in Table 3 below mitigate surveillance bias. Studies in Finnish and Russian populations indicate that the risk of developing symptoms may be proportional to the specific mutation in AIP.

Table 2. Frequencies of Porphyria (Open Table in a new window)

Type of Porphyria |

Age of Onset |

Incidence |

Male-to-Female Ratio |

ALAD deficiency |

Mostly adolescence to young adulthood, but variable (2-63 y) |

6 cases total |

6:0 |

AIP |

After puberty (third decade) |

General 0.01/1000 Sweden 1/1000 Finland 2/1000 France 0.3/1000 |

M>F |

HCP |

Predominantly adulthood (youngest patient aged 4 y) |

Japan 0.015/1000 Czech 0.015/1000 Israel 0.007/1000 Denmark 0.0005/1000 |

1:20 1:4 2:1 1:1 |

VP |

Heterozygous mutation: after puberty (fourth decade) Homozygous mutation (rare): childhood |

South Africa 0.34/1000 |

1:1 |

Mortality/Morbidity

Mortality is associated with secondary cardiovascular disease, chronic renal failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Catecholamine hypersecretion has been implicated in cases of sudden death. Long-term morbidity results from renal damage, hypertension, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric disturbances. [7]

A Norwegian study, by Baravelli et al, supported the contention that acute porphyria increases the risk of primary liver cancer (PLC), finding that, in comparison with the reference population, the adjusted hazard ratio for PLC in acute porphyria patients was 108. The investigators also conducted a literature review, which indicated that the risk of acute porphyria–related PLC is greater in women than in men. In addition, the authors found evidence that acute porphyria raises the risk of renal and endometrial cancer. [8]

Race

Certain ethnic groups are predisposed to porphyrias (see Table 2). Individuals of Swedish and Finnish descent have a high prevalence of AIP. Prevalence of VP is particularly high among South Africans of Danish descent.

Sex

The increased prevalence of acute porphyrias in women probably reflects the significant exacerbation by female sex hormones.

Age

Most patients with acute porphyria present after puberty, but the disease can occur in childhood. In female patients, acute porphyria is particularly evident after puberty, but its severity and overall prevalence after menopause. Patients with VP may present later in life than those with AIP.

-

Heme production pathway. Heme production begins in the mitochondria, proceeds into the cytoplasm, and resumes in the mitochondria for the final steps. Figure outlines the enzymes and intermediates involved in the porphyrias. Names of enzymes are presented in the boxes; names of the intermediates, outside the boxes. Multiple arrows leading to a box demonstrate that multiple intermediates are required as substrates for the enzyme to produce 1 product.