Background

For hundreds of years, societies have maintained a certain fascination with the bizarre and the unknown. In the past, persons with congenital disorders that cause excessive body-hair growth have been so dramatized and romanticized that individuals with rare hypertrichosis syndromes became crowd-drawing money-making phenomena in many 19th century sideshow acts. Most famously, Fedor Jeftichew, aka Jojo the Dog-faced boy, was exhibited by PT Barnum in the United States in the 1800s.

These individuals have been referred to as dog-men, hair-men, human Skye terriers, ape-men, werewolves, and Homo sylvestris. [1, 2] Since the Middle Ages, approximately 50 individuals with congenital hypertrichosis have been described; approximately 34 cases have been adequately and definitively documented in the literature. [3, 4, 5]

Disorders of hypertrichosis are distinguished by the distribution of hair, as well as by the temporal pattern of growth, the possible associated congenital anomalies, and the possible inheritance pattern. [6]

Congenital hypertrichosis lanuginosa (CHL) has been referred to variably as congenital hypertrichosis universalis, hypertrichosis universalis, hypertrichosis lanuginosa, and hypertrichosis lanuginosa universalis. The lack of definitive terminology can be confusing and may make the distinction of the related but unique hypertrichosis syndromes difficult. [1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22] Several solitary case reports describing hypertrichosis resembling CHL in association with other physical findings may, in fact, represent variants along a spectrum of the disorder.

An X-linked syndrome of hypertrichosis associated with gingival hyperplasia has been described. The abnormally excessive body hair that these patients develop is of the terminal type, and this disorder will not be greatly discussed. However, the X-linked syndrome of hypertrichosis associated with gingival hyperplasia is often confused with CHL. Julia Pastrana (1834-1860), one of the most famous persons with generalized hypertrichosis, was long thought to have CHL. After her death, her hairs were found to be actually terminal, indicating that she likely had hypertrichosis with gingival hyperplasia and not CHL. This illustrates the need for accurate determination of the type of excess hair present on a given patient.

In addition, the localized hypertrichoses, including primary hypertrichosis cubiti (hypertrichosis of both elbows), primary cervical hypertrichosis, and primary faun tail deformity, are not addressed in this article. [23] These forms represent limited types of hypertrichosis that may be associated with underlying bone and neurologic abnormalities. Hence, they can be distinguished from CHL on the basis of their clinical presentations.

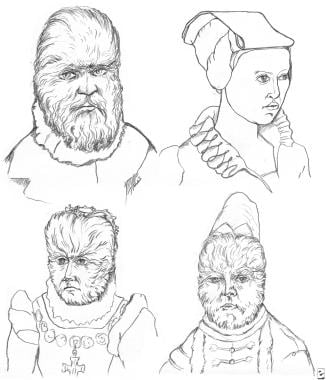

In 1648, Aldrovandus first documented a family with hypertrichosis (see the image below). Originally from the Canary Islands, Petrus Gonzales was brought to France as a curiosity for the nobles. He, his two daughters, a son, and a grandchild were affected. This kindred was dubbed the Family of Ambras after a castle near Innsbruck where their portraits were discovered. Over the next 300 years, more than 50 similar-appearing cases were described, and 34 patients with presumed congenital hypertrichosis were identified. In 1873, Virchow described an edentate form; in 1876, Bartles added the descriptor "universalis"; and in 1890, Chiari called the syndrome "hypertrichosis of the dog-men."

The hairy family of Burma has a four-generation pedigree of CHL dating back to 1826. Earlier generations were in the employ of the Ava court, but later generations often earned a living as sideshow attractions in the 1880s.

In 1993, Baumeister et al noted that nine of the 34 documented patients with hypertrichosis had a distinctive clinical presentation. [3] The term Ambras syndrome was coined (see the image below), and subsequent genetic analyses in two patients revealed an association with a paracentric inversion of band 8q22.

Pathophysiology

Two types of excessive hair disorders exist and must be distinguished from eahc other: hypertrichosis and hirsutism.

Hypertrichosis is a non-androgen-related pattern of excessive hair growth that may involve vellus, terminal, or lanugo type hair. It can accompany certain genetic syndromes, or it can be induced secondarily by exogenous medications—most notably, phenytoin, minoxidil, cyclosporine, diazoxide, corticosteroids, streptomycin, hexachlorobenzene, penicillamine, heavy metals, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, acetazolamide, and interferon. The hypertrichosis seen in Ambras syndrome is believed to result either from an increase in the number of hairs in anagen or from an increased number of follicular units, though no one knows for certain. [24]

Hirsutism, on the other hand, commonly occurs in women and presents as androgen-induced male-pattern hair growth of the terminal type. [25, 26, 27, 28] It may have a congenital or an exogenous origin. More common causes of hirsutism include polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), idiopathic hirsutism, hyperprolactinemia, hyperthecosis, and medications (eg, danazol, androgenic oral contraceptives). [29] Less common causes include congenital adrenal hyperplasia, ovarian tumors, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, granulosa–thecal cell tumors, other tumors that stimulate the ovarian stroma, adrenal tumors, Cushing disease, tumors of the adrenal cortex, and severe insulin-resistance syndromes. [30]

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa and transient neonatal cutis laxa have been described as the initial presenting signs in Sotos syndrome. Other features of the syndrome include excessive early childhood growth; learning disabilities or attention-deficit disorder; a long, narrow face; high forehead; red cheeks; and a pointed chin. [31]

Etiology

Congenital hypertrichosis lanuginosa

The pathogenesis of CHL is unknown. It is believed to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner; most cases involve a familial component. Variable expressivity of inherited characteristics is noted. The specific genetic abnormality in CHL has not been defined. No specific hormonal or endocrinologic abnormalities have been identified.

Evidence has suggested that some cases of CHL are not familial. These cases likely represent spontaneous mutations . [7, 32]

Ambras syndrome

A genetic etiology is proposed for Ambras syndrome. Two cases of this syndrome [3, 33] were found to be associated with alterations in chromosome 8. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), Tadin et al analyzed the original patient described by Baumeister and detected a pericentric inversion of chromosome 8, inv(8)(p11.2q22). [34]

In an analysis of findings in the second patient reported by Balducci, an association was made with an insertion of the q23-24 region into a more proximal region of the long arm of chromosome 8, most likely at the q13 band, as well as a complex deletion in 8q23 encompassing four separate chromosomal breakpoints. [33] The inversion breakpoints in this latter patient have been cloned, and a detailed map of the inversion breakpoint interval has been generated. [35]

Although it remains unclear precisely how these genetic observations are related to the pathogenesis of hypertrichosis, it has been postulated that the common breakpoint at 8q22 in these two patients with Ambras syndrome suggests that this region of chromosome 8 contains a gene involved in regulation of hair growth.

Epidemiology

US and international statistics

CHL and Ambras syndrome are extremely rare, with fewer than 50 cases documented worldwide. [2, 3, 36, 37] The incidence of CHL has not been precisely defined; however, the reported incidence has ranged from 1 in a billion to 1 in 10 billion. [7, 21, 38, 39] Neither CHL nor Ambras syndrome has been shown to have any geographic predilection.

Age-, sex-, and race-related demographics

In both CHL and Ambras syndrome, excessive hair is apparent at birth.

Patients with CHL have growth of lanugo hair, which increases in length and extent of involvement from birth to approximately age 2 years (range, 1-8 y). The density, length, and extent of involvement may then decrease; the rate of hair growth also slows. Many individuals with CHL lose most, if not all, of their lanugo hair over time, and eventually, only limited areas of hypertrichosis may be present. Occasionally, the lanugo hair may be totally lost by the time the patient becomes an adult. A variant in which patients do not lose their lanugo hair over time is called congenital hypertrichosis universalis or persistent hypertrichosis universalis. [40]

Individuals with Ambras syndrome are classically described as having hypertrichosis at birth; however, the quantity of the excessive hair may be limited at that time. Unlike patients with CHL, those with Ambras syndrome may show increased hair growth in terms of both distribution and density as they age, and the hair does not spontaneously involute.

No sex predilection is known.

No racial predilection is recognized.

Prognosis

In CHL, hair growth occurs until an average patient age of 2 years; afterward, hair regresses during adolescence. [22] In Ambras syndrome, patients are described as having increased hair growth throughout their lifetime.

CHL is not associated with increased mortality, nor have any associated long-term medical or physical morbidities been documented. Psychological sequelae may occur because of the presence of excessive hair growth and the maintenance involved in removing the unwanted hair.

Patient Education

Patients should be made aware that hypertrichosis may have a genetic component and therefore may be inherited by subsequent generations. They should also be made aware that the genetic basis for CHL has not been identified but that the overall health of individuals with hypertrichosis is good.

-

Family of Petrus Gonzales, who lived in the 16th century.

-

Patients in well-documented cases of Ambras syndrome. (A) Daughter of Petrus Gonzales. (B) Grandson of Schwe Maong. (C) Adrrian Jepticheff. (D) Fedor.