Practice Essentials

Limp is defined by a deviation from the normal gait pattern expected for a child's age. [1] It can be a challenging problem for the emergency or pediatric practitioner, as causes span multiple organ systems and anatomic locations. The differential diagnosis may be categorized based on acuity of presentation, age of the patient, etiology, type of gait disturbance, or anatomic location of suspected pathology.

Diagnostic entities range from trivial causes such as a rock in the shoe to potentially life- and limb-threatening causes such as septic arthritis and malignancy (see the image below). The possibility of serious pathology underlying an acute presentation of limp makes accurate assessment, diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and appropriate follow-up essential.

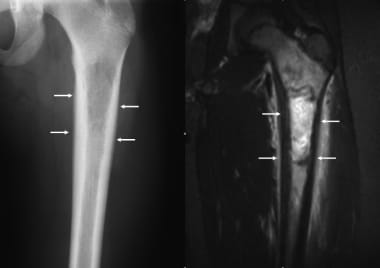

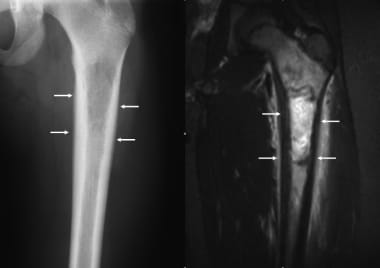

Ewing sarcoma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the femur in a 14-year-old male shows an ill-defined permeative lytic lesion of the proximal femur, with lamellated periosteal reaction (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery MRI image demonstrated a tumor within the proximal femur, with reactive bone marrow edema. Lamellated periosteal reaction is present (arrows), and edema is seen in the adjacent soft tissues. The tumor was biopsy-proven as Ewing sarcoma.

Ewing sarcoma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the femur in a 14-year-old male shows an ill-defined permeative lytic lesion of the proximal femur, with lamellated periosteal reaction (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery MRI image demonstrated a tumor within the proximal femur, with reactive bone marrow edema. Lamellated periosteal reaction is present (arrows), and edema is seen in the adjacent soft tissues. The tumor was biopsy-proven as Ewing sarcoma.

Pathophysiology

Walking is the culmination of the successful integration of numerous biomechanical systems. Almost every major system of the body can be involved. Ultimately, any process affecting the upper or lower motor neurons, motor end plates, musculature, bony structures, or joints may manifest as a limp.

Upper motor neuron lesions, such as brain anoxia and cerebral palsy, may be detected in the spastic gait (toe walking and/or scissoring where the knees and thighs hit each other, or cross in a scissors-like movement) of an afflicted child. Destruction of the dorsal columns may result from neurosyphilis or spinal column space-occupying lesions, leading to loss of proprioception and subsequent slapping or steppage gait, where the foot hangs with the toes pointing down, causing the toes to scrape the ground while walking, requiring someone to lift the leg higher than normal when walking.

Peripheral nerve palsies, such as hereditary motor sensory neuropathy (including Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease) or posttraumatic peroneal nerve palsy, can also result in a steppage gait.

Musculoskeletal pathology of the lower extremity and back most often lead to an antalgic gait where the stance phase of gait is abnormally shortened relative to the swing phase. These may be traumatic, infectious, inflammatory, or rheumatologic in nature. Toddler's fractures, abuse injuries, sprains, and avascular necrosis (eg, vertebrae, femur, tarsals, metatarsals) are all possible contributors to the antalgic gait. Joint pathology, such as idiopathic avascular necrosis of the hip (Legg-Calve-Perthes disease), may cause a Trendelenburg gait; during the stance phase, the weakened abductor muscles allow the pelvis to tilt down on the opposite side. To compensate, the trunk lurches to the weakened side to attempt to maintain a level pelvis throughout the gait cycle and the pelvis sags on the opposite side.

Posttraumatic, infectious, or degenerative back and spine disease can also produce alterations in gait.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The incidence of limping is not known.

International statistics

While little published data exist, one European study found the incidence of atraumatic limp in children aged 1-14 years to be 180 cases per 100,000, or every 58th visit to a pediatric emergency department. [2]

Sex- and age-related demographics

Sex

Limping due to trauma and trauma-related conditions (eg, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, toxic synovitis, tibial osteitis, groin strains) is observed more commonly in males than in females.

Incidence of congenital conditions (eg, limp associated with congenital hip dysplasia and meningomyelocele) corresponds to the sex predilection of the underlying condition.

Some systemic illnesses associated with limping (eg, rheumatoid arthritis [RA], systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]) have a predilection for females.

Age

Age group of the patient may be one of the most helpful factors in narrowing the initial differential diagnosis of limping:

Toddlers (aged 1-3 y)

These children are ambulatory and active but have immature gaits and are thus prone to falls, typically with a torsional component.

Infections play a major role, as the bony cortex is developing and its ability to resist bacterial invasion is limited.

Causes of limp in the toddler are infectious/inflammatory (eg, transient synovitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis), trauma (eg, toddler's fracture [see the image below], stress fractures, puncture wounds, lacerations), neoplasm, developmental dysplasia of the hips, neuromuscular disease, cerebral palsy, and congenital hypotonia.

Toddler's fracture. Reproduced with permission from Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Volume 4, Case 18, Melinda D. Santhany, MD. Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children, University of Hawaii, John A. Burns School of Medicine.

Toddler's fracture. Reproduced with permission from Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Volume 4, Case 18, Melinda D. Santhany, MD. Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children, University of Hawaii, John A. Burns School of Medicine.

Children (aged 4-10 y)

As a child ages and becomes more physically active, high-energy injuries, such as fractures, dislocations, and ligamentous injuries become more common.

Microtrauma to the vascular supply of the femoral head is thought to be a cause of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCP), a common source of limping in this age group. See the image below.

Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Patient with a painful hip and limp for several months. Reproduced with permission from Loren Yamamoto, Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Patient with a painful hip and limp for several months. Reproduced with permission from Loren Yamamoto, Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

Infections continue to plague this age group. Terminal vessels occur in the metaphysis of growing bones, which is a common site for infection.

Rheumatoid conditions begin to emerge.

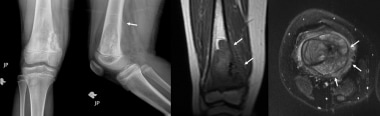

Neoplastic lesions such as leukemia (see the first image below) and Ewing sarcoma (see the second image below) can occur.

Knee radiographs in leukemia. Oblique radiographs of the knee show lucent metaphyseal bands, which are seen in 90% of patients with leukemia.

Knee radiographs in leukemia. Oblique radiographs of the knee show lucent metaphyseal bands, which are seen in 90% of patients with leukemia.

Ewing sarcoma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the femur in a 14-year-old male shows an ill-defined permeative lytic lesion of the proximal femur, with lamellated periosteal reaction (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery MRI image demonstrated a tumor within the proximal femur, with reactive bone marrow edema. Lamellated periosteal reaction is present (arrows), and edema is seen in the adjacent soft tissues. The tumor was biopsy-proven as Ewing sarcoma.

Ewing sarcoma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the femur in a 14-year-old male shows an ill-defined permeative lytic lesion of the proximal femur, with lamellated periosteal reaction (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery MRI image demonstrated a tumor within the proximal femur, with reactive bone marrow edema. Lamellated periosteal reaction is present (arrows), and edema is seen in the adjacent soft tissues. The tumor was biopsy-proven as Ewing sarcoma.

Adolescents (older than 11 y)

The bony architecture is more mature and resilient, and muscle strength also has increased dramatically.

A slipped capital femoral epiphysis is an example of how bone maturation, strength, and weight mismatches can result in problems (see the image below).

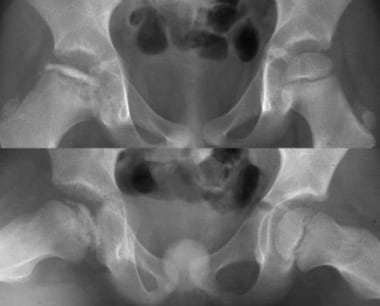

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Anteroposterior pelvis in an overweight13-year-old adolescent girl shows widening of the epiphyseal plate with irregular margins. Frog leg lateral views shows posteromedial displacement of the femoral head.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Anteroposterior pelvis in an overweight13-year-old adolescent girl shows widening of the epiphyseal plate with irregular margins. Frog leg lateral views shows posteromedial displacement of the femoral head.

At this age, arthritis, sexually transmitted diseases (with arthralgias and arthritis), and neoplasms may present as a limp.

Other common causes of limping in the adolescent are juvenile arthritis (see the first image below), trauma, leg length discrepancy, and neoplasms such as osteosarcoma (see the second image below).

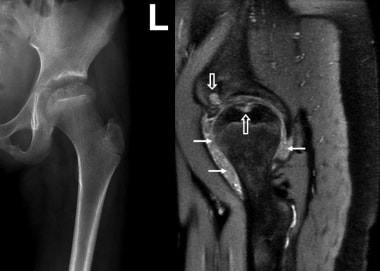

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Anteroposterior radiograph of the hip shows ballooning of the femoral metaphysis and flattening of the femoral epiphysis, with erosion of the femoral head. On the sagittal T2-weighted image, a joint effusion with prominent nodular synovitis is observed (arrows). Erosions are seen in the acetabulum and femoral head (open arrows).

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Anteroposterior radiograph of the hip shows ballooning of the femoral metaphysis and flattening of the femoral epiphysis, with erosion of the femoral head. On the sagittal T2-weighted image, a joint effusion with prominent nodular synovitis is observed (arrows). Erosions are seen in the acetabulum and femoral head (open arrows).

Osteosarcoma. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs in a 9-year-old girl shows a destructive lesion of the distal femoral metaphysis medially, with aggressive sunburst periosteal reaction and a Codman's triangle on the lateral view (arrow). Coronal T1-weighted and axial T2-weighted images showing an expansile tumor of the distal femur with cortical destruction and extension into the soft tissues (arrows).

Osteosarcoma. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs in a 9-year-old girl shows a destructive lesion of the distal femoral metaphysis medially, with aggressive sunburst periosteal reaction and a Codman's triangle on the lateral view (arrow). Coronal T1-weighted and axial T2-weighted images showing an expansile tumor of the distal femur with cortical destruction and extension into the soft tissues (arrows).

Prognosis

The prognosis varies depending upon the etiology.

Although relatively uncommon, a few "can't miss" causes of pediatric limp may cause significant morbidity and mortality. Among 243 patients visiting one pediatric emergency department, 1.6% were diagnosed with osteomyelitis, 2.1% were diagnosed with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, and 0.8% were diagnosed with a neoplasia. [3] No patients in this cohort had a septic arthritis or fracture related to child abuse. Thus, the incidence of these conditions and other life- and limb-threatening conditions presenting as a limp are poorly characterized.

Complications

Left untreated, a slipped capital femoral epiphysis can result in permanent gait abnormalities.

Early treatment of several disorders that may cause limping can result in resolution or at least limit the extent of the injury.

The degree to which intervention will play a role is entirely dependent on the etiology of the limp.

-

Toddler's fracture. Reproduced with permission from Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Volume 4, Case 18, Melinda D. Santhany, MD. Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children, University of Hawaii, John A. Burns School of Medicine.

-

Demonstration of Galeazzi test to evaluate for leg length discrepancy.

-

Demonstration of FABER test to evaluate for sacro-iliac joint pathology.

-

Demonstration of prone internal rotation. The maneuver increases intracapsular pressure in the hip and will not be tolerated by a patient with an inflammatory process.

-

Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Patient with a painful hip and limp for several months. Reproduced with permission from Loren Yamamoto, Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

-

Transient synovitis. Ultrasound image of the left hip shows a large joint effusion. The fluid was aspirated leading to complete resolution of symptoms. No organisms were grown, and the diagnosis was transient synovitis.

-

Ewing sarcoma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the femur in a 14-year-old male shows an ill-defined permeative lytic lesion of the proximal femur, with lamellated periosteal reaction (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery MRI image demonstrated a tumor within the proximal femur, with reactive bone marrow edema. Lamellated periosteal reaction is present (arrows), and edema is seen in the adjacent soft tissues. The tumor was biopsy-proven as Ewing sarcoma.

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Anteroposterior radiograph of the hip shows ballooning of the femoral metaphysis and flattening of the femoral epiphysis, with erosion of the femoral head. On the sagittal T2-weighted image, a joint effusion with prominent nodular synovitis is observed (arrows). Erosions are seen in the acetabulum and femoral head (open arrows).

-

Knee radiographs in leukemia. Oblique radiographs of the knee show lucent metaphyseal bands, which are seen in 90% of patients with leukemia.

-

Osteochondroma. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the left leg in a 10-year-old boy with hereditary multiple exostoses showing multiple osteochondromas (arrows).

-

Osgood-Schlatter disease. Lateral radiograph of the left knee showing fragmentation of the tibial tubercle with overlying soft tissue swelling, consistent with Osgood-Schlatter disease.

-

Osteoid osteoma. Anteroposterior film of the femur in a 10-year-old boy shows cortical thickening of the medial aspect of the distal femur (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery demonstrates a high signal intensity lesion in the medial cortex, with associated bone marrow edema, biopsy proven to be an osteoid osteoma.

-

Osteomyelitis. Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis in a 16-month-old boy shows erosion and lucency of the metaphysis in the right proximal femur (arrows). Coronal inversion recovery image show a joint effusion in the right hip. Extensive bone marrow edema is present in the femoral metaphysis, with edema in the surrounding soft tissues.

-

Osteosarcoma. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs in a 9-year-old girl shows a destructive lesion of the distal femoral metaphysis medially, with aggressive sunburst periosteal reaction and a Codman's triangle on the lateral view (arrow). Coronal T1-weighted and axial T2-weighted images showing an expansile tumor of the distal femur with cortical destruction and extension into the soft tissues (arrows).

-

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Anteroposterior pelvis in an overweight13-year-old adolescent girl shows widening of the epiphyseal plate with irregular margins. Frog leg lateral views shows posteromedial displacement of the femoral head.

-

Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Anteroposterior and frog leg lateral radiographs of the pelvis in a 8-year-old girl shows fragmentation and collapse of the left femoral capital epiphysis.

-

Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis in a 2-year-old child demonstrates a shallow acetabulum on the right, with lateral uncovering of the femoral head. The left hip appears unremarkable.