Practice Essentials

Priapism (see the image below) is an involuntarily prolonged erection that is unrelieved by orgasm/ejaculation. It can be generally divided into two subcategories: ischemic and nonischemic. [1] Ischemic priapism, which constitutes approximately 95% of cases, is a true urologic emergency, and early intervention allows the best chance for functional recovery. [2, 1]

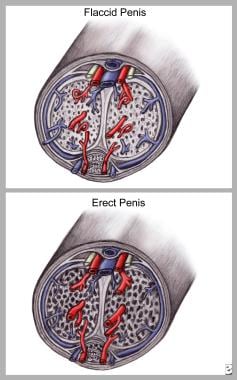

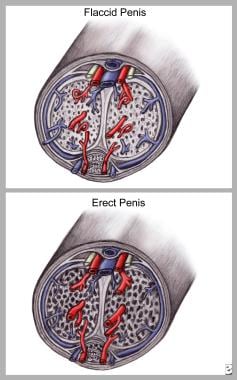

Priapism. Corporeal relaxation causes external pressure on the emissary veins exiting the tunica albuginea, trapping blood in the penis and causing erection.

Priapism. Corporeal relaxation causes external pressure on the emissary veins exiting the tunica albuginea, trapping blood in the penis and causing erection.

Signs and symptoms

Low-flow priapism (ischemic - 95% of cases)

This condition is generally painful, although the pain may fade in prolonged episodes. Characteristics of low-flow priapism include the following:

-

Rigid erection

-

Ischemic corpora (as indicated by dark, acidotic, hypercarbic, and hypoxic blood upon corporal aspiration)

-

Soft glans

-

No clinical history or evidence of trauma

High-flow priapism (nonischemic - 5% of cases)

This type of priapism is generally not painful and may manifest in an episodic manner. Characteristics of high-flow priapism include the following:

-

Adequate arterial flow (waveform visible on penile duplex ultrasound

-

Well-oxygenated corpora (on corporal blood gas testing)

-

Evidence of trauma: Blunt or penetrating injury to the penis or perineum (straddle injury is often the initiating event), also common after successful aspiration/irrigation/shunt for treatment of ischemic priapism.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The goal of the initial diagnostic evaluation is to confirm or exclude ischemic priapism (because ischemic cases require emergent intervention) as well as any

Background

Priapism is defined as an abnormal persistent erection of the penis. It is usually painful (95% of cases) and it is unrelated to sexual stimulation and unrelieved by orgasm/ejaculation. Priapism is frequently idiopathic but it is a known complication of a number of important medical conditions and pharmacologic agents (see Etiology). [6]

Priapism must be quickly stratified as either low-flow (ischemic) or high-flow (nonischemic), because the causes and treatments are different. Low-flow priapism, which is by far the most common type, results from failure of the detumescence mechanism (ie inability to achieve venous outflow), whereas high-flow priapism results from uncontrolled arterial inflow, often through a fistula or pseudoaneurysm caused by genitourinary trauma. Additionally, low-flow priapism often converts to high-flow during the course of treatment, particularly after distal shunt maneuvers.

Treatment of low-flow priapism should progress in a stepwise fashion, starting with therapeutic aspiration, with or without irrigation, and/or intracavernous injection of a sympathomimetic agent. [7] Treatment of high-flow priapism is initially conservative, but cases that persist beyond several months may warrant angiography and obliteration of fistula and/or pseudoaneurysm within the cavernosal arteries.

Low-flow priapism is a true urologic emergency that may lead to permanent erectile dysfunction and significant penile length loss due to corporal fibrosis if left untreated. Early intervention allows the best chance for functional recovery [6] ; as with many medical emergencies, the saying "time is tissue" holds true for priapism.

Pathophysiology

The penis has 3 corporeal bodies: 2 corpora cavernosa (responsible for erectile rigidity) and 1 corpus spongiosum (urethral tissue). Erection is the result of smooth-muscle relaxation and increased arterial flow into the corpora cavernosa, causing engorgement and rigidity (see image below). In priapism, the corpus spongiosum and glans penis are typically not engorged but blood is trapped within the corpora cavernosa, creating a form of compartment syndrome.

Priapism. Corporeal relaxation causes external pressure on the emissary veins exiting the tunica albuginea, trapping blood in the penis and causing erection.

Priapism. Corporeal relaxation causes external pressure on the emissary veins exiting the tunica albuginea, trapping blood in the penis and causing erection.

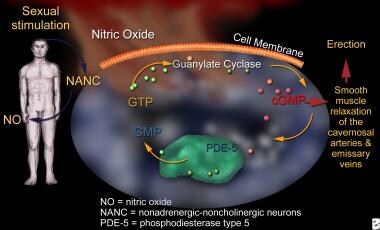

Engorgement of the corpora cavernosa compresses the venous outflow tracts (ie, subtunical venules), trapping blood within the corpora cavernosa. The major neurotransmitter that controls erection is nitric oxide, which is secreted by the endothelium that lines the corpora cavernosa (see the image below). These events occur in both normal and pathologic erections.

Priapism. Sexual stimulation causes the release of nitric oxide (NO) via stimulation of nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurons. NO-activated intracellular guanylate cyclase, converting guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), causes relaxation of cavernosal arteries and increased penile blood flow, resulting in erection.

Priapism. Sexual stimulation causes the release of nitric oxide (NO) via stimulation of nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurons. NO-activated intracellular guanylate cyclase, converting guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), causes relaxation of cavernosal arteries and increased penile blood flow, resulting in erection.

Pathophysiologically, priapism can be of either a low-flow (ischemic) or a high-flow (nonischemic) type. Low-flow priapism, which is by far the most common type, results from failure of venous outflow, whereas high-flow priapism results from uncontrolled arterial inflow with preserved venous outflow. Clinically, differentiation of low-flow from high-flow priapism is critical, because treatment for each is different.

Low-flow priapism may be due to any of the following:

-

An excessive release of neurotransmitters

-

Blockage of draining venules (eg, mechanical interference in sickle cell crisis, leukemia, or excessive use of intravenous parenteral lipids)

-

Paralysis of the intrinsic detumescence mechanism

-

Prolonged relaxation of the intracavernous smooth muscles (most common etiology of ischemic priapism and typically caused by the use of exogenous smooth-muscle relaxants such as injectable intracavernosal agents (eg, alprostadil) for erectile dysfunction (ED) or for prolongation of sexual encounters in patients who do not have ED.

Prolonged ischemic priapism leads to a painful ischemic state, which can cause fibrosis of the corporal smooth muscle and cavernosal artery thrombosis. The degree of ischemia is a function of the number of emissary veins involved and the duration of occlusion. Light-microscopy studies have demonstrated that corporeal tissue becomes thickened, edematous, and fibrotic after days of priapism.

Further studies with electron microscopy have demonstrated trabecular interstitial edema after 12 hours of priapism and destruction of sinusoidal endothelium, exposure of the basement membrane, and thrombocyte adherence after 24 hours of priapism. At 48 hours, thrombi were evident in the sinusoidal spaces, and smooth-muscle cell histopathologic findings varied from necrosis to fibroblast-like cell transformation. Priapism for longer than 24 hours is associated with permanent impotence in as many as 90% of patients.

High-flow priapism is the result of uncontrolled arterial inflow from a fistula or pseudoaneurysm between the cavernosal artery and the corpus cavernosum. This is generally secondary to blunt or penetrating injury to the penis or perineum causing rupture of a cavernous artery. It is usually not painful but is characterized by persistent erection with soft glans.

Etiology

Priapism can be idiopathic or can be secondary to a variety of diseases, conditions, or medications. In the United States, the most common cause of priapism in the adult population involves injectable agents used to treat erectile dysfunction. Internationally, most cases are idiopathic.

The most common cause of priapism in the pediatric population is sickle cell disease (SCD), which is responsible for 65% of cases. One study found that in unscreened children with SCD, priapism was the first presentation in 0.5% of cases [4] Leukemia, trauma, and idiopathic causes are the causes in 10% of patients. Pharmacologically induced priapism is the etiology in 5% of children. [8] Other secondary causes of low-flow priapism are the following thromboembolic/hypercoagulable states:

-

Dialysis

-

Vasculitis

-

Fat embolism (from multiple long-bone fractures or intravenous infusion of lipids as part of total parenteral nutrition)

Neurologic diseases that can result in low-flow priapism include the following:

-

Spinal cord stenosis (ie, trauma to the medulla)

-

Autonomic neuropathy and cauda equina compression

Neoplastic disease (metastatic to the penis or obstructive to venous outflow) that can result in low-flow priapism include the following [9] :

-

Prostate cancer

-

Bladder cancer (highest risk)

-

Hematologic cancer (leukemia)

-

Melanoma

Pharmacologic causes of low-flow priapism include the following:

-

Intracavernosal agents - Papaverine, phentolamine, prostaglandin E1

-

Intraurethral pellets (ie, medicated urethral system for erection with intracavernosal prostaglandin E1)

-

Antihypertensives - Ganglion-blocking agents (eg, guanethidine), arterial vasodilators (eg, hydralazine), alpha-antagonists (eg, prazosin), calcium channel blockers

-

Psychotropics - Phenothiazine, butyrophenones (eg, haloperidol), perphenazine, trazodone, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram) [5]

-

Anticoagulants - Heparin, warfarin (during rebound hypercoagulable states)

-

Recreational drugs - Cocaine [11]

-

Hormones - Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), tamoxifen, testosterone, androstenedione for athletic performance enhancement

-

Herbal medicine - Ginkgo biloba with concurrent use of antipsychotic agents [12]

-

Miscellaneous agents - Metoclopramide, omeprazole, penile injection of cocaine, epidural infusion of morphine and bupivacaine [13]

Contrary to popular belief even among medical personnel, the risk of priapism in patients using phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors for ED (ie, sildenafil, vardenafil, tadalafil, avanafil) is extraordinarily low. One study showed that even among patients presenting with drug-induced priapism, only 2.9% were found to be taking PDE5 inhibitors. [14] In fact, several reports suggest sildenafil as a means to treat priapism and as a possible means of preventing full-blown episodes in patients with sickle cell disease, particularly in the setting of stuttering priapism. [15]

High-flow priapism may result from the following forms of genitourinary trauma:

-

Straddle injury

-

Intracavernous injections resulting in direct cavernosal artery injury

-

Invasive treatments for low-flow priapism

Rare causes of priapism include the following:

-

Amyloidosis (massive amyloid infiltration)

-

Gout (one case report)

-

Black widow spider bites [16]

-

Asplenia

-

Fabry disease (rare association, occasionally noted to be priapism of the high-flow type)

-

Vigorous sexual activity

-

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (mechanism is thought to be a hypercoagulable state induced by the infection)

Epidemiology

A review of United States emergency department visits with a primary diagnosis of priapism from 2006 to 2009 determined that the annual incidence rate was 5.34 per 100,000 males. The rate of visits was 31.4% higher in summer months than in winter months. [17]

The frequency of priapism varies in different populations. The combination of intracavernosal agents and other drugs is the cause of approximately 67-80% of all adult priapism in the United States.The overall rate of priapism in persons using agents to treat erectile dysfunction ranges from 0.05-6%. This group tends to be better educated about the risk of priapism; therefore, they seek treatment earlier.

In other population groups, sickle cell disease (SCD) and sickle cell trait predominate as the cause of adult priapism. The rate of priapism in adults with SCD is as high as 89%. In one study, 38-42% of adult males with SCD reported at least one episode of priapism. Approximately two thirds of all pediatric patients who have priapism also have SCD. The rate of priapism among children with SCD is as high as 27%.

Internationally, the overall incidence of priapism is 1.5 cases per 100,000 person-years. In men older than 40 years, the incidence increases to 2.9 cases per 100,000 person-years. [18, 19]

Racial, sexual, and age-related differences in incidence

No racial predilection toward priapism exists. SCD, which predisposes to the development of priapism, occurs mostly in the African-American population.

Priapism is almost exclusively a disease of males. Priapism of the clitoris has been reported but is extremely rare. [20, 21]

Priapism has been described at nearly all ages, from infancy through old age. A bimodal distribution has been noted, with peaks at 5-10 years and 20-50 years. [18] Cases in younger groups are more often associated with SCD, while those in older groups tend to be secondary to pharmacologic agents.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the duration of the episode, the patient's age, and the underlying pathology. Duration is the single most important factor affecting outcome. A Scandinavian study reported that 92% of patients with priapism for less than 24 hours remained potent, while only 22% of patients with priapism that lasted longer than 7 days remained potent. [3]

All patients with priapism should be warned about the long-term risk of erectile dysfunction (ED). The warning should also be clearly written on the discharge instruction sheet and documented in the chart. In general, vaso-occlusive priapism poses a higher risk of ED than does high-flow arterial priapism. Sickle cell disease appears to particularly increase risk: a study by Anele and Burnett found that patients with sickle cell disease who experience even minor episodes of recurrent ischemic priapism are five times more likely to develop ED compared with non–sickle cell patients. [22]

Patients who have experienced an episode of priapism are at risk for recurrence. A review of 3,372 men who presented to emergency departments with priapism found that within 1 year, 24% of patients were readmitted for recurrent priapism. Of those, 68% were readmitted within 60 days. [23]

Infection can complicate priapism. In cases resulting from trauma, the source of the infection may be the trauma itself, or it may be iatrogenic. Corporeal fibrosis due to persistent priapism can result in susceptibility to deep-tissue infections of the penis.

Deaths have been reported in patients with sickle cell disease presenting with priapism, but the cause of death usually is not related to the priapism per se but to complications from the underlying disease process.

A study of 10,459 men with priapism, identified from an insurance database, reported an increased risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in the years following an episode of priapism. Compared with a matched cohort of men with other urologic disorders of sexual dysfunction (ED, Peyronie disease, premature ejaculation), men with priapism showed a subsequent increased incidence of ischemic heart disease (hazard ratio [HR] 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09-1.42) and other heart disease (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.12-1.38), as well as incident cerebrovascular disease (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.15-1.55). [24]

Patient Education

Education is the best way to avoid undesirable outcomes. Any high-risk patient, especially a man using oral or intracavernosal agents for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, must understand that a persistent erection is a possibility and that prompt medical attention is critical if it should occur.

Patients presenting with priapism deserve special counseling, beginning with the first episode of priapism. Patients must understand that a poor outcome is possible despite appropriate and timely management.

For patient education resources, see Erectile Dysfunction and Priapism.

-

Priapism. Corporeal relaxation causes external pressure on the emissary veins exiting the tunica albuginea, trapping blood in the penis and causing erection.

-

Priapism. Sexual stimulation causes the release of nitric oxide (NO) via stimulation of nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurons. NO-activated intracellular guanylate cyclase, converting guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), causes relaxation of cavernosal arteries and increased penile blood flow, resulting in erection.

-

Priapism. Winter shunt placed by biopsy needle, usually under local anesthetic.

-

Priapism. Proximal cavernosal-spongiosum shunt (Quackel shunt) surgically connects the proximal corpora cavernosa to the corpora spongiosum.

-

Priapism. Proximal cavernosal-saphenous shunt (Grayhack shunt) surgically connects the proximal corpora cavernosum to the saphenous vein.