Background

Benign positional vertigo (BPV), also known as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), is the most common cause of vertigo. Vertigo is an illusion of motion (an illusion is a misperception of a real stimulus) and represents a disorder of the vestibular proprioceptive system.

BPV was first described by Adler in 1897 and then by Bárány in 1922; however, Dix and Hallpike did not coin the term benign paroxysmal positional vertigo until 1952. This terminology defined the characteristics of the vertigo and introduced the classic provocative diagnostic test that is still used today. Using positional testing, benign positional vertigo can readily be diagnosed in the emergency department. Benign positional vertigo is one of the few neurologic entities the emergency physician can cure at the patient's bedside by performing a series of simple and safe head-hanging maneuvers.

Pathophysiology

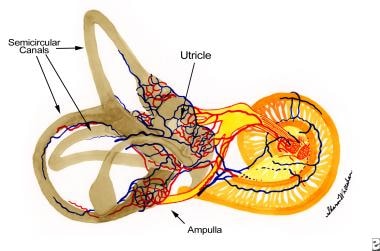

Benign positional vertigo (BPV) is caused by calcium carbonate particles called otoliths (or otoconia) that are inappropriately displaced into the semicircular canals of the vestibular labyrinth of the inner ear. These otoliths are normally attached to hair cells on a membrane inside the utricle and saccule. Because the otoliths are denser than the surrounding endolymph, changes in vertical head movement causes the otoliths to tilt the hair cells, which sends a signal informing the brain that the head is tilting up or down.

The utricle is connected to the 3 semicircular canals. The otoliths may become displaced from the utricle by aging, head trauma, or labyrinthine disease. When this occurs, the otoliths have the potential to enter the semicircular canals. When they do, they usually enter the posterior semicircular canal because this is the most dependent (inferior) of the 3 canals, and so gravitational forces will result in most otoliths entering the posterior canal.

According to the canalolithiasis theory (the most widely accepted theory describing the pathophysiology of benign positional vertigo), the otoliths are free-floating within the semicircular canal. Changing head position causes the misplaced otoliths to continue to move through the canal after head movement has stopped. As the otoliths move, endolymph moves along with them and this stimulates the hair cells of the cupula of the affected semicircular canal, sending a signal to the brain that the head is turning when it is not. This results in the sensation of vertigo. When the otoliths stop moving, the endolymph also stops moving and the hair cells return to their baseline position, thus terminating the vertigo and nystagmus. Reversing the head maneuver causes the particles to move in the opposite direction, producing nystagmus in the same axis but reversed in direction of rotation. The patient may describe that the room is now spinning in the opposite direction. When repeating the head maneuvers, the otoliths tend to become dispersed and thus are progressively less effective in producing the vertigo and nystagmus (hence, the concept of fatigability).

Epidemiology

Frequency

The incidence of benign positional vertigo (BPV) is 64 cases per 100,000 population per year (conservative estimate). [1]

Mortality/Morbidity

The B of BPV stands for benign and designates that the cause of the vertigo is peripheral to the brainstem and, hence, likely to be benign. However, BPV can be severely incapacitating to the patient.

Demographics

Women are affected twice as often as men.

BPV, in general, is a disease of elderly persons, although onset can occur at any age. Several large studies show an average age of onset in the mid 50s. Vertigo in young patients is more likely to be caused by labyrinthitis (associated with hearing loss) or vestibular neuronitis (normal hearing).

Prognosis

Benign positional vertigo (BPV) tends to resolve spontaneously after several days or weeks. Patients may experience recurrences months or years later (if the otoliths got out once, they can do it again).

Variants range from a single, short-lived episode to decades of vertigo with only short remissions.

A study by Kim et al assessed patients who were discharged home from the ED with a diagnosis of isolated dizziness or vertigo and determined that stroke occurs in less than 1 in 500 patients within the first month. [2] Cerebrovascular risk factors should be considered for individual patients.

-

Anatomy of the semicircular canals.

-

Epley maneuver. Move the patient back in the gurney such that when he lies down, his or her head will hang over the edge of the gurney. Emphasize to the patient to keep his or her eyes open during each position so that nystagmus can be observed. Lower the guardrails of the gurney on the opposite side from which the patient's head is turned.

-

Epley maneuver. Turn the patient's head 45° to the side that had the most prominent symptoms during the Hallpike test. In this example, the patient's head is turned 45° to the left. With both hands holding the patient's head, gently lay the patient down in the supine position with the head hanging over the edge of the bed. Note: Each maneuver does not need to be performed rapidly. The Epley maneuver is positional, not positioning.

-

Epley maneuver. The patient's head should be at 45° and hanging off the edge of the bed. Observe the patient's eyes and look for torsional nystagmus. Keep the patient in this position for at least 30 seconds or until the nystagmus or symptoms resolve.

-

Epley maneuver. Because the patient's head will be turned 90° in the other direction, the physician needs to move to the head of the gurney and regrip the patient's head so that the fingers are pointing toward the patient's feet.

-

Epley maneuver. Turn the patient's head 90° in the opposite direction (in this case, the patient's head is now facing to the right). Again, observe for nystagmus and hold this position for at least 30 seconds or until nystagmus or symptoms resolve.

-

Epley maneuver. Close-up view of step shown in Media file 6.

-

Epley maneuver. Ask the patient to turn onto his or her shoulder.

-

Epley maneuver. Guide the patient's head down so that he or she is looking at the ground. Again, wait for at least 30 seconds.

-

Epley maneuver. Close-up of view shown in Media file 9.

-

Epley maneuver. The patient's head needs to be regripped again. Then, the patient needs to sit up with the legs hanging over the side of the gurney (which is why the guardrails need to be lowered before the start of the procedure).

-

Epley maneuver. The patient is now sitting upright.

-

Epley maneuver. Move the patient's head slightly forward. This completes the Epley maneuver. The maneuver may be performed multiple times.

-

Hallpike test. In this example, the right posterior semicircular canal is being tested. Note that the head extends over the edge of the gurney. The thumb can be used to help keep the eyelids open since noting the direction of the nystagmus is important.

-

Epley maneuver. In this example, the left posterior semicircular canal is being treated. In this clip, the maneuvers are performed quickly. In a real patient, each position should be held for at least 30 seconds or until resolution of the nystagmus and vertigo.

-

Semont maneuver. Generally reserved for the cupulolithiasis form of benign positional vertigo, in which the otoliths are attached to the cupula of the semicircular canal. This maneuver has to be performed rapidly to be effective, and it is not recommended in elderly persons. In this example, the right posterior semicircular canal is being treated.

-

Bar-b-que maneuver. This maneuver is used to treat horizontal canal benign positional vertigo. In this example, the right horizontal canal is being treated. Each position should be held at least 20-30 seconds.