Background

Trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the motile parasitic protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. It is one of the most common STIs, both in the United States and worldwide.

The high prevalence of T vaginalis infection globally and the frequency of coinfection with other STIs make trichomoniasis a compelling public health concern. Research has shown that T vaginalis infection is associated with an increased risk for infection with several STIs, including gonorrhea, human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and, most importantly, HIV. Trichomoniasis is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, infertility, postoperative infections, and cervical neoplasia.

T vaginalis may be transmitted vertically to newborns, causing vaginitis, urinary tract infection, and/or respiratory infection that can be life-threatening.

Humans are the only known host of T vaginalis. Transmission occurs predominantly via sexual intercourse. The organism is most commonly isolated from vaginal secretions in women and urethral secretions in men. The rectal prevalence of T vaginalis among men who have sex with men (MSM) appears low. Although T vaginalis has not been isolated from oral sites, evidence suggests that it may cause sexually transmitted oral infection in rare cases.

Women with trichomoniasis may be asymptomatic or may experience various symptoms, including vaginal discharge and vulvar irritation. Men with trichomoniasis may experience nongonococcal urethritis but are frequently asymptomatic.

Trichomonas vaginalis infections in men have often been regarded as benign and, as a result, have received insufficient attention. However, men infected with this common STI may suffer from conditions such as urethritis, prostatitis, reduced fertility, and an increased risk of contracting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Additionally, many men are asymptomatic, allowing them to unknowingly transmit the infection to their female partners. With advancements in diagnostics for T vaginalis, more men are being identified as infected; however, the most effective treatment approach for men is still not well established.

Trichomoniasis is thought to be widely underdiagnosed owing to various factors, including a lack of routine testing, the low sensitivity of a commonly used diagnostic technique (wet mount microscopy), and nonspecific symptomatology. Self-diagnosis and self-treatment or diagnosis by practitioners without adequate laboratory testing also may contribute to misdiagnosis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends numerous molecular detection methods to diagnose trichomoniasis, including several validated nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) and an antigen-detection test.

Testing for T vaginalis infection is recommended in all women seeking care for vaginal discharge, in addition to screening for T vaginalis in women at high risk for STI.

The CDC recommends two oral nitroimidazoles for the treatment of trichomoniasis: metronidazole (Flagyl) and tinidazole (Tindamax). Although generally more expensive, tinidazole is associated with fewer adverse effects than metronidazole and is equal or superior in resolving T vaginalis infection. When the first-line agent is ineffective (and reinfection by partner is ruled out), the other nitroimidazole or an alternative dosing schedule of metronidazole may be used. Topical metronidazole and other antimicrobials are not efficacious and should not be used to treat trichomoniasis.

Sexual partners of the infected patient should also be treated. Both the patient and partners should abstain from sexual activity until pharmacologic treatment has been completed and they have no symptoms. In regions where expedited partner therapy (EPT) is legal, it may be useful in managing trichomoniasis. Infected women who are sexually active have a high rate of reinfection; thus, rescreening at 3 months posttreatment should be considered. Data are insufficient to support rescreening men.

Pathophysiology

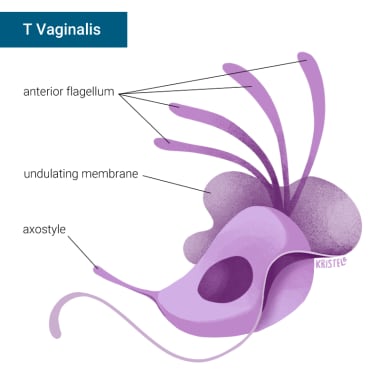

T vaginalis trichomonads are approximately the size of white blood cells (about 10-20 μm long and 2-14 μm wide), although this may vary. Trichomonads have four flagella that project from the organism’s anterior and one flagellum that extends backward across the middle of the organism, forming an undulating membrane. An axostyle, a rigid structure, extends from the organism’s posterior.

Trichomonas vaginalis. (A) Two trophozoites of T vaginalis obtained from in vitro culture, stained with Giemsa. (B) Trophozoite of T vaginalis in vaginal smear, stained with Giemsa. Images courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Trichomonas vaginalis. (A) Two trophozoites of T vaginalis obtained from in vitro culture, stained with Giemsa. (B) Trophozoite of T vaginalis in vaginal smear, stained with Giemsa. Images courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

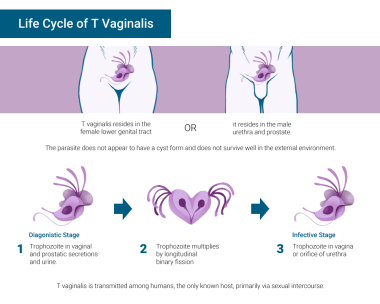

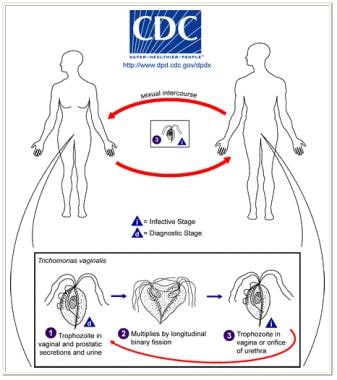

In women, T vaginalis is isolated from the vagina, cervix, urethra, bladder, and Bartholin and Skene glands. In men, the organism is found in the anterior urethra, external genitalia, prostate, epididymis, and semen (see the image below). It resides both in the lumen and on the mucosal surfaces of the urogenital tract and uses flagella to move around vaginal and urethral tissues. T vaginalis has also been isolated from the rectum and detected via molecular techniques in the respiratory tract, although these are not common areas of infection. In cases of vertical transmission, T vaginalis may infect the respiratory systems of infants; however, little is known about this condition.

Life cycle of Trichomonas vaginalis. T vaginalis trophozoite resides in female lower genital tract and in male urethra and prostate (1), where it replicates by binary fission (2). The parasite does not appear to have a cyst form and does not survive well in the external environment. T vaginalis is transmitted among humans, the only known host, primarily via sexual intercourse (3). Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Life cycle of Trichomonas vaginalis. T vaginalis trophozoite resides in female lower genital tract and in male urethra and prostate (1), where it replicates by binary fission (2). The parasite does not appear to have a cyst form and does not survive well in the external environment. T vaginalis is transmitted among humans, the only known host, primarily via sexual intercourse (3). Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

T vaginalis destroys epithelial cells by direct cell contact and by the release of cytotoxic substances. It also binds to host plasma proteins, thereby preventing recognition of the parasite by the alternative complement pathway and host proteinases. During infection, the vaginal pH increases, as does the number of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). PMNs are the predominant host defense mechanism against T vaginalis and respond to chemotactic substances released by trichomonads. The presence of antigen-specific peripheral blood mononuclear cells may also suggest that lymphocyte priming occurs during infection. Antibody response to T vaginalis infection has been detected both locally and in serum.

Despite the immune system’s interaction with T vaginalis, infection produces an immunity that is only partially protective at best, and there is little evidence that a healthy immune system prevents infection. One study showed no association between trichomoniasis and the use of protease inhibitors or immune status in HIV-infected women. Another showed that HIV seropositivity did not alter the rate of infection in males.

Symptoms of trichomoniasis typically occur after an incubation period of 4-28 days. Infection generally persists for fewer than 10 days in males. The persistence of asymptomatic infection in women is unknown. Older women have been shown to have significantly higher rates of infection than younger women, which suggests that asymptomatic infection may persist for long durations in women.

Etiology

The risk of acquiring T vaginalis infections is based on engagement in high-risk sexual activity. Those who engage in the following sexual practices are at a greater risk for infection:

-

New or multiple partners

-

Exchanging sex for money or drugs

-

Sexual contact with an infected partner

-

Not using barrier protection

Several other factors may indicate a higher likelihood of T vaginalis infection but may not be directly or causally linked, as follows:

-

A history of certain STIs

-

Current STIs

-

A history of injection drug use

Even if not directly causal, these factors may be predictive. In a study that considered risk factors for trichomoniasis, injection drug use in the preceding 30 days was the most strongly associated with infection and with new infection observed during the study.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

According to the CDC's treatment guidelines, trichomoniasis is estimated to be the most prevalent nonviral STI worldwide, and it affects approximately 2.6 million people in the United States. However, this figure may not fully capture the true prevalence of the infection, which is believed to be around 8 million cases annually. The discrepancy arises because trichomoniasis is not nationally reportable, and many infections are asymptomatic, making exact numbers difficult to obtain. Additionally, the commonly used wet mount technique for diagnosis has low sensitivity, leading to further underestimation of prevalence.

Trichomoniasis has a higher prevalence in women compared to men. In the United States, from 2013 to 2016, the prevalence of the infection among individuals aged 14 to 59 years was 2.1% in women and 0.5% in men.

International statistics

Trichomoniasis represents a significant global disease burden, particularly among women in low-income areas and individuals aged 30 to 54 years. From 1990 to 2021, the estimated annual percentage change in the global age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of trichomoniasis was 0.09. In 2021, the global ASIR was 4133.41 cases per 100,000 people, with men experiencing a higher rate (4353.43 per 100,000) compared to women (3921.31 per 100,000). However, the disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rate was significantly higher in women than in men, at 6.45 versus 0.23 per 100,000. Among women aged 30 to 54 years, the trend in ASIR closely mirrored the overall population incidence trend. Additionally, the highest ASIRs were observed in low socio-demographic index (SDI) regions, with projected ASIRs by 2050 estimated at 5680.57 per 100,000 for males and 5749.47 per 100,000 for females.

Age-related demographics

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Study found a prevalence of 2.3% among adolescents aged 18-24 years and 4% among adults 25 years and older. A prevalence of 3.1% in females aged 14-49 years was observed based on a nationally representative sample of women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001-2004 study. Despite this trend, trichomoniasis remains a concern in younger women. In female adolescents, trichomoniasis is more common than gonorrhea, which is particularly disconcerting given that it increases susceptibility to other infections.

In a study of men attending an STI clinic in Denver, the prevalence of Trichomonas infection was 0.8% in men younger than 30 years and 5.1% in men 30 years and older. This increase in prevalence is believed to result from age-related enlargement of the prostate gland.

Vertical transmission of T vaginalis during birth is possible and may persist up to 1 year, causing UTI, and, less commonly, respiratory infection. Between 2% and 17% of female offspring of infected women acquire infection.

Sex-related demographics

T vaginalis is not classified as a reportable infection, leading to prevalence estimates that primarily rely on modeling or ad hoc population-based studies. The World Health Organization estimated in 2016 that the global prevalence of T vaginalis was 5.0% in women and 0.6% in men, with prevalence rates among men ranging from 0.2% to 1.3%. The highest rates are observed in Africa and the Americas. In the United States, an estimated 4.1 million infections occurred among men in 2018. Data from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) revealed a prevalence of 0.5% in men aged 18–59 years, compared to 1.8% in women. This survey marked the first national prevalence data for T vaginalis in US men and utilized the highly sensitive Hologic Gen-Probe Aptima T vaginalis nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for diagnosis.

In the United States, significant racial and socioeconomic disparities exist regarding T vaginalis infections. Research indicates that Black men are seven times more likely to be infected than White men. Other factors associated with higher rates include low educational attainment, poverty, being unmarried, and having more than five lifetime sexual partners. Among men who have sex with men (MSM), T vaginalis is a rare cause of urethral and rectal infections, with studies showing no cases of infection in MSM using highly sensitive NAAT tests. Recent estimates indicate that T vaginalis prevalence among asymptomatic men ranges from 6% to 20% among symptomatic men in Africa, and between 4% to 17% among men attending US STI clinics. The higher prevalence in symptomatic men may be linked to the lack of screening recommendations for asymptomatic individuals.

Race-related demographics

In the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Study, significant differences in the prevalence of trichomoniasis among adolescents were noted by race: white, 1.2%; Asian, 1.8%; Latino, 2.1%; Native American, 4.1%; and African American, 6.9%. Considerable differences were also observed in the national NHANES 2001-2004 study conducted among women ages 14-49: non-Hispanic whites, 1.2%; Mexican Americans, 1.5%; and non-Hispanic blacks, 13.5%.

Evidence suggests that T vaginalis infection likely increases HIV transmission and that coinfection with HIV complicates treatment of trichomoniasis. Control of T vaginalis may represent an important means of slowing HIV transmission, particularly among African Americans, in whom higher rates have been observed.

Daugherty et al screened a representative sample of men aged 18-59 years with RNA testing for T vaginalis and found that 0.49% were infected.

Prognosis

Trichomoniasis can usually be treated quickly and effectively. Recurrent infections are common in sexually active patients. One study found that 17% of sexually active patients with T vaginalis infection were reinfected at 3-month follow-up. Multiple randomized trials have found that this rate of reinfection can be significantly reduced through expedited partner therapy.

T vaginalis infection is also strongly associated with the presence of other STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, and sexually transmitted viruses. T vaginalis infection has even been shown to increase a patient’s susceptibility to sexually transmitted viruses, including herpes simplex virus, human papillomavirus, and HIV. Persons with trichomoniasis are twice as likely to develop HIV infection as the general population. One potential explanation for this is that T vaginalis disrupts the epithelial monolayer, leading to increased passage of the HIV virus. Another posits that T vaginalis induces immune activation, specifically lymphocyte activation and replication and cytokine production, leading to increased viral replication in HIV-infected cells. Further research is needed to clarify the exact mechanism by which T vaginalis increases the risk for HIV infection.

Women may experience various complications associated with trichomoniasis. One study reported a higher risk of pelvic inflammatory disease in women with trichomoniasis. Other studies have reported a 1.9-fold risk of tubal infertility in women with trichomoniasis. Trichomoniasis may also play a role in cervical neoplasia and postoperative infections.

Pregnant women with T vaginalis infection are at an especially high risk for adverse outcomes, which may include the following:

-

Preterm delivery

-

Low birth-weight offspring

-

Premature rupture of membranes

-

Intrauterine infection

-

Respiratory or genital T vaginalis infection in the newborn

T vaginalis infection may also increase the likelihood of vertical HIV transmission owing to disruption of the vaginal mucosa.

Male infertility

Researchers conducted a study involving 197 male volunteers seeking medical care for infertility issues, collecting urine and semen samples to investigate the frequency of trichomoniasis. The average age of participants ranged from 36 to 40 years, with 181 individuals experiencing fertility problems compared to 16 with normal fertility. Spermogram analysis revealed that 48% of participants had non-motile or progressive sperm, and 48% exhibited abnormalities in sperm morphology. Whereas microscopic examination did not detect T vaginalis, molecular analysis using PCR and sequencing identified one case of trichomoniasis in a 33-year-old infertile man, who had only 0.3% normal sperm and 19% motility. The isolated T vaginalis was classified as the G genotype.

The study highlights that trichomoniasis in males has often been deemed unimportant, with the assumption that it would resolve on its own. However, the findings suggest that parasites may be a contributing factor to male infertility, although the extent of their impact remains unclear. This investigation underscores the effectiveness of molecular techniques in detecting trichomoniasis in males, indicating a need for further exploration of its role in infertility.

Patient Education

Education concerning STI treatment and prevention is vital (see Prevention). Because T vaginalis infection is strongly associated with the presence of other STIs (gonorrhea, chlamydia, and sexually transmitted viruses such as HIV), providers should provide appropriate counseling, testing, and treatment for such infections.

Upon diagnosis of trichomoniasis, healthcare providers should discuss treatment, including the adverse effects and interactions encountered with metronidazole and tinidazole. It is especially important to warn patients to abstain from alcohol when taking metronidazole and tinidazole. Providers should also address the treatment of sexual partners and, where allowed by law, employ expedited partner therapy. Individuals with trichomoniasis who notify partners of their infection help disrupt the transmission of trichomoniasis and other STIs.

Providers should also discuss methods of preventing T vaginalis reinfection. It may be important to explain that T vaginalis infection may be longstanding and not due to a recent sexual encounter.

The CDC advises providers to consider rescreening sexually active women at 3 months after the completion of treatment. There are insufficient data to recommend rescreening of sexually active men, but it may be desired if reinfection is likely.

Pregnant women exhibiting symptoms, regardless of the stage of their pregnancy, should undergo testing and receive treatment. Addressing T vaginalis infections can alleviate symptoms such as vaginal discharge in pregnant women and minimize the risk for sexual transmission to partners. Although perinatal transmission of trichomoniasis is rare, treatment may also help prevent respiratory or genital infections in newborns. Clinicians should provide counseling to symptomatic pregnant individuals diagnosed with trichomoniasis, discussing the potential risks and benefits of treatment, as well as emphasizing the importance of treating partners and using condoms to prevent sexual transmission. The effectiveness of routine screening for T vaginalis in asymptomatic pregnant people has not yet been determined. See the patient education fact sheet below.

-

Trichomonas vaginalis on a saline wet mount at 40X on the microscope. Several motile parasites transit through the field, surrounded by white blood cells and squamous epithelial cells.

-

Life cycle of Trichomonas vaginalis. T vaginalis trophozoite resides in female lower genital tract and in male urethra and prostate (1), where it replicates by binary fission (2). The parasite does not appear to have a cyst form and does not survive well in the external environment. T vaginalis is transmitted among humans, the only known host, primarily via sexual intercourse (3). Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Trichomonas vaginalis. (A) Two trophozoites of T vaginalis obtained from in vitro culture, stained with Giemsa. (B) Trophozoite of T vaginalis in vaginal smear, stained with Giemsa. Images courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Trichomoniasis overview.

-

Trichomoniasis life cycle.