Background

Retinal artery occlusion (RAO) usually presents as painless loss of monocular vision. [1, 2] Ocular stroke commonly is caused by embolism of the retinal artery, although emboli may travel to distal branches of the retinal artery, causing loss of only a section of the visual field. Retinal artery occlusion represents an ophthalmologic emergency, and delay in treatment may result in permanent loss of vision. [3]

Immediate intervention improves chances of visual recovery, but, even then, prognosis is poor, with only 21-35% of eyes retaining useful vision. Although restoration of vision is of immediate concern, RAO is a harbinger for other systemic diseases that must be evaluated immediately.

Pathophysiology

Blood supply to the retina originates from the ophthalmic artery, the first intracranial branch of the internal carotid artery that supplies the eye via the central retinal and the ciliary arteries. The central retinal artery supplies the retina as it branches into smaller segments upon leaving the optic disc. The ciliary arteries supply the choroid and the anterior portion of the globe via the rectus muscles (each rectus muscle has 2 ciliary arteries except the lateral rectus, which has 1).

Anatomic variants include cilioretinal branches from the short posterior ciliary artery, giving additional supply to part of the macular retina. A cilioretinal artery occurs in approximately 14% of the population.

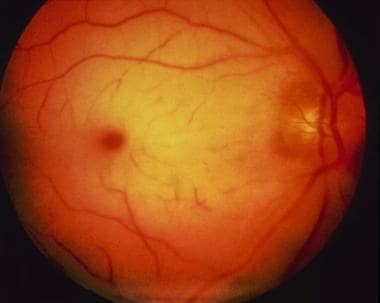

Typical funduscopic findings of a pale retina with a cherry red macula (ie, the cherry red spot) result from obstruction of blood flow to the retina from the retinal artery, causing pallor, and continued supply of blood to the choroid from the ciliary artery, resulting in a bright red coloration at the thinnest part of the retina (ie, macula). These findings do not develop until an hour or more after embolism, and they resolve within days of the acute event. By this time, vision loss is permanent and primary optic atrophy has developed. In those with a cilioretinal artery supplying the macula, a cherry red spot is not observed. [3]

An embolism, atherosclerotic changes, inflammatory endarteritis, angiospasm, or hydrostatic arterial occlusion may occlude the retinal artery. The mechanism of obstruction may be obvious from comorbid systemic disease or physical findings. Atrial fibrillation and ipsilateral carotid stenosis are more commonly associated with prolonged visual disturbances. [3]

Animal studies have shown that a retina with completely occluded circulation has irreversible ischemic damage at 105 minutes but may recover at 97 minutes. Complete occlusion of retinal artery circulation in humans is rare with retinal artery disease; thus, retinal recovery is possible even after days of ischemia.

Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) occurs when the embolus lodges in a more distal branch of the retinal artery. [1, 4] Branch retinal artery occlusion typically involves the temporal retinal vessels and usually does not require ocular therapeutics unless perifoveolar vessels are threatened. The central retinal artery is affected in 57% of occlusions, the branch retinal artery is involved in 38% of occlusions, and cilioretinal artery obstructions occur in 5% of occlusions. [5]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Estimates put the incidence of RAO at 0.85 per 100,000 per year, with a 10-year cumulative incidence of retinal emboli of 1.5%. [6]

A retrospective cohort study from South Korea explored the epidemiology of RAO from 2002 to 2018. [7] It identified 51,326 patients with RAO, predominantly male (56.2%), with an average age of 63.6 years at diagnosis. The nationwide incidence of RAO was reported as 7.38 per 100,000 person-years. Specifically, the incidence rate of noncentral RAO was 5.12 per 100,000 person-years, more than double that of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) at 2.25 per 100,000 person-years.

Mortality/Morbidity

Mortality rates associated with RAO vary significantly across studies, reflecting inconsistencies due to small sample sizes and varying follow-up durations. For example, individual studies have reported mortality rates ranging from 5.4% to 29.6% over periods from 2.2 to 11 years, while a pooled analysis from two population-based cohort studies over a decade reported a 56% mortality rate among RAO patients, nearly double that of non-RAO individuals. A comprehensive nationwide study observed a 13.8% mortality rate among 51,326 patients with newly diagnosed RAO over 14 years, with a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of 7.33, indicating significantly higher mortality compared to the general population. This SMR was higher for CRAO than for noncentral RAO, and notably higher in women than in men, with younger patients under 50 years showing exceptionally high SMRs.

The primary causes of death in RAO patients are cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases, with acute myocardial infarction being the most frequent. This underscores the strong link between RAO and systemic cardiovascular conditions, further supported by the high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases at diagnosis. The association with risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia underscores the need for comprehensive cardiovascular evaluation and management in RAO patients to address immediate risks and mitigate long-term cardiovascular complications. [8, 9] Additionally, RAO is linked to smoking and significantly increases the risk for stroke, affecting both eyes equally with bilateral involvement in 1-2% of cases, highlighting the severe prognosis associated with CRAO compared to noncentral RAO. [7]

Sex

Men are affected slightly more frequently than women.

Age

The mean age of presentation of RAO is early in the seventh decade of life, although a few cases have been reported in patients younger than 30 years. [10]

The etiology of occlusion changes, depending on the age at presentation.

Prognosis

The recovery of useful vision is closely linked to the speed of intervention and the initial visual acuity at presentation.

Research indicates that 21% of patients experienced an improvement of six levels in visual acuity, 35% improved by three levels, and 26% showed no improvement at all. [11] Patients who improved typically had an initial visual acuity of counting fingers and experienced vision loss for an average of 21.1 hours. In contrast, those who did not improve had an initial visual acuity of hand movement and experienced vision loss for an average of 58.6 hours.

The maximum delay in treatment that still resulted in significant visual recovery is documented to be approximately 72 hours. The presence of a cilioretinal artery with foveolar sparing is associated with better outcomes in visual acuity.

Branch retinal artery occlusions (BRAOs) generally have a higher likelihood of recovery, with 80% of cases improving to 20/40 vision or better. In contrast, CRAOs often result in severe vision loss, which remains profound despite treatment. Once retinal infarction sets in, which can occur as quickly as 90 minutes after the occlusion, the vision loss becomes permanent. [1]

Prompt diagnosis and treatment of underlying giant cell arteritis can protect vision in the unaffected eye and potentially restore some vision in the affected eye.

Patient Education

Patients must understand that the prognosis for visual recovery is poor and that the visual changes are usually a result of a systemic process that needs treatment.

-

The cherry red spot of central retinal artery occlusion.