Embryology

The developmental precursors of the nose are the neural crest cells, which commence their caudad migration toward the midface around the fourth week of gestation. Two nasal placodes develop inferiorly in a symmetrical fashion. Nasal pits divide the placodes into medial and lateral nasal processes. The medial processes become the septum, philtrum, and premaxilla of the nose, whereas the lateral processes form the sides of the nose. Inferior to the nasal complex, the stomodeum, or future mouth, forms (see the image below).

A nasobuccal membrane separates the oral cavity inferiorly from the nasal cavity superiorly. As the olfactory pits deepen, the choanae are formed. Primitive choanae form initially, but with continued posterior development, the secondary or permanent choanae develop. By 10 weeks, differentiation into muscle, cartilage, and bony elements occurs. Failure of these carefully orchestrated events in early facial embryogenesis may result in multiple potential anomalies, including choanal atresia, medial or lateral nasal clefts, nasal aplasia, and polyrrhinia. [1] Neonates are obligate nasal breathers for the first 6 weeks. When bilateral choanal atresia is present in a neonate, emergency action is needed.

Developmental Milestones: [2, 3]

-

Weeks 4-5 - Migration of neural crest cells; formation of nasal placodes and pits

-

Week 6 - Fusion of medial

Skin and Soft Tissues

Like the underlying bony cartilaginous framework of the nose, the overlying skin may also be divided into vertical thirds. The skin of the upper third is fairly thick but tapers into a thinner, mid-dorsal region. The inferior third regains the thickness of the upper third owing to the more sebaceous nature of the skin in the nasal tip. The dorsal skin is usually the thinnest of the three sections of the nose. Difference in the skin thickness must be appreciated during dorsal reduction to avoid complications or over-reduction. [4]

Nasal muscles are encountered deep to the skin and consist of four principal groups: the elevators, depressors, compressor, and dilators.

Elevators include the procerus and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi. The procerus muscle is responsible for creating horizontal lines across the bridge of the nose, often involved in expressions of concentration or frowning. The levator labii superioris alaeque nasi plays a role in elevating the upper lip and dilating the nostrils, contributing to facial expressions such as disdain or anger. [2]

The depressors are made up of the alar nasalis and depressor septi nasi. These muscles are involved in the downward movement of the nasal tip and nostrils, affecting the nasal shape during expressions such as sadness or fatigue. [2]

The transverse nasalis acts as the compressor of the nose, playing a role in narrowing the nostrils. [2]

The dilator naris anterior and posterior are responsible for widening the nostrils, facilitating increased air intake during respiratory activities. [2]

The muscles are interconnected by an aponeurosis termed the nasal superficial musculoaponeurotic system. This structure provides a framework that supports muscle function and skin movement, contributing to both dynamic and static facial expressions. [2]

The internal nasal lining consists of squamous epithelium in the vestibule. This transitions to pseudostratified ciliated columnar respiratory epithelium with abundant seromucinous glands within the nose, which helps maintain moisture and trap particulates from the inhaled air. [2]

Subunit principal

The external soft tissue of the nose can be divided into subunits. The purpose of subunits is to divide the nasal anatomy into segments useful for reconstruction. If more than 50% of the subunit is lost, one would strive to replace the whole unit with regional tissue or tissue from a donor site. The subunits include the dorsal nasal segment, lateral nasal wall segments, hemilobule segment, soft tissue triangle segments, alar segments, and columellar segment (see the image below).

Modern approaches emphasize the matching of skin texture, color, and contour during reconstruction. This is particularly important for the lower third of the nose, where aesthetic outcomes are the most critical. For upper regions such as the dorsum and sidewalls, defect-only reconstruction may still yield satisfactory results. While full subunit replacement is ideal for large defects, partial subunit replacement or direct defect repair has been shown to achieve good outcomes in select cases. These modifications are often employed when functional preservation or donor site limitations are considered. Reconstructing entire subunits helps to manage trapdoor contraction, a phenomenon where scar tissue causes a bulging deformity in the reconstructed areas. By restoring the entire subunit, surgeons can better mimic natural nasal contours. [5, 6]

Contemporary algorithms guide surgeons in selecting appropriate techniques based on the defect size, location, and patient-specific factors. For example: [5, 6]

-

Small defects (< 1.5 cm) may be closed with local flaps or grafts.

-

Intermediate defects (1.5-2.5 cm) often require bilobed flaps or composite grafts.

-

Larger defects necessitate regional flaps such as the paramedian forehead flap.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The nose, like the rest of the face, receives abundant blood supply, which plays a vital role in its physiological functions such as warming and humidifying the inhaled air as well as in immune defense. [7]

The arterial supply to the nose may be principally divided into:

(1) Branches from the internal carotid, namely branches of the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries from the ophthalmic artery. These arteries supply the superior nasal septum and lateral nasal wall, including portions of the superior and middle turbinates. [2, 8, 9]

(2) Branches from the external carotid, namely the sphenopalatine, greater palatine, superior labial, and angular arteries. [2, 8, 9]

-

The sphenopalatine artery (a terminal branch of the maxillary artery) supplies the posterior and inferior portions of the nasal cavity, including the middle and inferior turbinates.

-

The greater palatine artery supplies the posterior septum and nasal floor.

-

The superior labial artery (a branch of the facial artery) supplies the anterior septum.

-

The angular artery (a continuation of the facial artery, coursing over the superomedial aspect of the nose) supplies parts of the external nose.

The sellar and dorsal regions of the nose are supplied by branches of the internal maxillary artery (namely, the infraorbital) and ophthalmic arteries (which are from the internal carotid system).

Internally, the lateral nasal wall is supplied by the sphenopalatine artery posteroinferiorly and by the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries superiorly. The nasal septum also derives its blood supply from the sphenopalatine and the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries with the added contribution of the superior labial artery (anteriorly) and the greater palatine artery (posteriorly). The Kiesselbach plexus, or the Little area, represents a region in the anteroinferior third of the nasal septum where all three of the chief blood supplies to the internal nose converge.

Veins in the nose essentially follow the arterial pattern. They are significant for their direct communication with the cavernous sinus and for their lack of valves; these features potentiate the intracranial spread of infection. The cavernous turbinate plexuses in the nasal cavity make the nose susceptible to blockage. This plexus is similar to that found in the erectile tissue. [2] Even with the abundant blood supply of the nose, smoking does compromise postoperative healing.

The lymphatic drainage of the nose is divided into two main pathways: [2, 9]

-

Anterior nasal cavity - Drains into the submandibular lymph nodes via superficial lymphatics

-

Posterior nasal cavity - Drains into the retropharyngeal nodes and upper deep cervical nodes. Additionally, the upper nasal cavity has connections with the subarachnoid space along the olfactory nerves. These nodes are crucial for filtering lymphatic fluid before it enters systemic circulation.

Studies have highlighted distinctive features of nasal lymphatics. Lymphatic vessels in the nasal mucosa exhibit unique markers such as LYVE1-negative/VEGFR3-positive endothelial cells in certain areas. Two types of lymphatic capillaries have been identified: one with sharp-ended "zipper-like" junctions in the respiratory mucosa and another with round-ended "button-like" junctions near the squamous mucosa and nasal-associated lymphoid tissue. These capillaries play critical roles in immune surveillance by facilitating immune cell migration. [10]

Nerves

The sensation of the nose is derived from the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve. The following outline effectively delineates the respective sensory distribution of the nose and the face of the trigeminal nerve.

Ophthalmic division

The ophthalmic division includes the following:

-

Lacrimal - Skin of the lateral orbital area except the lacrimal gland

-

Frontal - Skin of the forehead and scalp, including the supraorbital (eyelid skin, forehead, and scalp) and supratrochlear (medial eyelid and medial forehead) skin

-

Nasociliary - Skin of the nose and mucous membrane of the anterior nasal cavity

On a more detailed level, the nasociliary portion of the ophthalmic division includes the following:

-

Anterior ethmoid - Anterior half of the nasal cavity: (1) internal, ethmoid and frontal sinuses and (2) external, nasal skin from the rhinion to the tip

-

Posterior ethmoid - Superior half of the nasal cavity, namely the sphenoid and ethmoids

-

Intratrochlear - Medial eyelids, palpebral conjunctiva, nasion, and bony dorsum

Maxillary division

The maxillary division includes the following:

-

Maxillary

-

Infraorbital - External nares

-

Zygomatic

-

Superior posterior dental

-

Superior anterior dental - Mediates the sneeze reflex

-

Sphenopalatine - Divides into lateral and septal branches and conveys sensation from the posterior and central regions of the nasal cavity

Parasympathetic nerve supply

The parasympathetic supply is derived from the greater superficial petrosal (GSP) branch of cranial nerve VII. The GSP joins the deep petrosal nerve (sympathetic supply), which comes from the carotid plexus to form the Vidian nerve in the Vidian canal. The Vidian nerve travels through the pterygopalatine ganglion (with only the parasympathetic nerves forming synapses here) to the lacrimal gland and glands of the nose and palate via the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve.

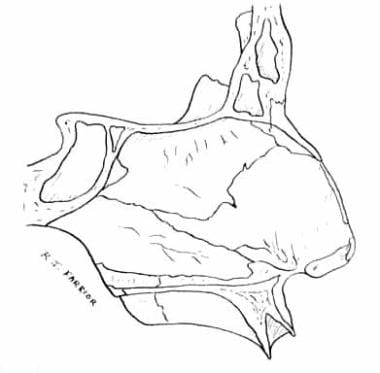

Bony Anatomy

Superiorly, the paired nasal bones are attached to the frontal bone (see the images below). Superolaterally, they are connected to the lacrimal bones, and inferolaterally, they are attached to the ascending processes of the maxilla. Posterosuperiorly, the bony nasal septum is composed of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, shown in the second image below. The vomer lies posteroinferiorly, which in part forms the choanal opening into the nasopharynx. The floor consists of the premaxilla and the palatine bones.

The quadrangular cartilage, the vomer, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and aspects from the premaxilla and palatine bones form the nasal septum.

The quadrangular cartilage, the vomer, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and aspects from the premaxilla and palatine bones form the nasal septum.

The lateral nasal walls contain three pairs each of small, thin, shell-like bones: the superior, middle, and inferior conchae, which form the bony framework of the turbinates. Lateral to these curved structures lies the medial wall of the maxillary sinus.

Inferior to the turbinates lies a space called a meatus, with names that correspond to the above turbinate, e.g., superior turbinate and superior meatus. The roof of the nose internally is formed by the cribriform plate of the ethmoid. Posteroinferior to this structure, sloping down at an angle, is the bony face of the sphenoid sinus.

Cartilaginous Pyramid

The cartilaginous septum extends from the nasal bones in the midline above to the bony septum in the midline posteriorly, then down along the bony floor. It assumes a quadrangular shape. Anteriorly, it is composed of hyaline cartilage, while posteriorly, it transitions into the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone through endochondral ossification. The septum serves as structural support for the nasal dorsum and contributes to midface development. It is surrounded by a perichondrium, which provides vascular supply and structural integrity. [11]

Its upper half is flanked by two triangular-to-trapezoidal cartilages, called the upper lateral cartilages, which are fused to the dorsal septum in the midline and attached to the bony margin of the pyriform aperture laterally by loose ligaments. The inferior ends of the upper lateral cartilages are free. The internal area or angle formed by the septum and upper lateral cartilage constitutes the internal valve, which is critical for regulating airflow. This valve is defined by the angle between the upper lateral cartilage and the septum. [2]

Adjacent sesamoid cartilages may be found lateral to the upper lateral cartilages in the fibroareolar connective tissue. These are found variably.

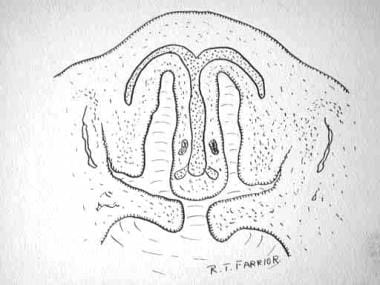

Beneath the upper lateral cartilages lie the lower lateral cartilages, as shown below. The paired lower lateral cartilages swing out from medial attachments to the caudal septum in the midline, called the medial crura, to an intermediate crus area. They finally flare out superolaterally as the lateral crura. These cartilages are frequently mobile, in contradistinction to the upper lateral cartilages. The medial crura provide support for the columella, while the lateral crura contribute to nostril shape and stability. An intermediate crus connects these two regions, ensuring smooth transitions in nasal contour. [2, 12]

In some individuals, evidence of a scroll may exist, i.e., an outcurving of the lower borders of the upper lateral cartilages and an incurving of the cephalic borders of the alar cartilages. Several variations exist, as depicted below.

Structure

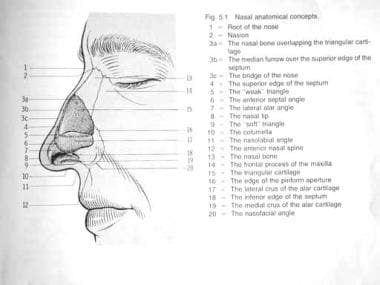

External nasal anatomy

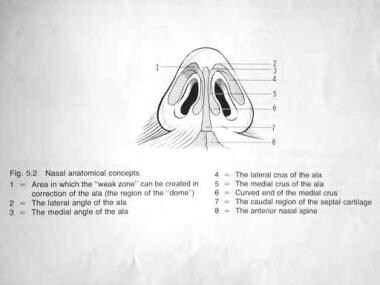

The first image below depicts the external nasal anatomy. Nasal subunits include the dorsum, sidewalls, hemilobules, alae, soft triangles, and columella. [13] Ethnic influences can result in different appearances of the nose [14] as follows: Caucasian, leptorrhine; African American, platyrrhine; Hispanic, paraleptorrhine; and Asian, subplatyrrhine. The external valve is a variable area dependent on the size, shape, and strength of the lower lateral cartilage.

Internal nasal anatomy

The septum is a midline bony and cartilaginous structure that divides the nose into two similar halves. Regarding the lateral nasal wall and paranasal sinuses, the superior, middle, and inferior concha form the corresponding superior, middle, and inferior meatus on the lateral nasal wall. The superior meatus is a drainage area for the posterior ethmoid cells and the sphenoid sinus. The middle meatus is a drainage area for the anterior ethmoid and the maxillary and frontal sinuses. The inferior meatus is a drainage area for the nasolacrimal duct. [13]

The internal nasal valve involves an area that is bounded by the upper lateral cartilage, septum, nasal floor, and anterior head of the inferior turbinate. This makes up the narrowest portion of the nasal airway in a leptorrhine nose. Generally, an angle wider than 15° is needed in this area. The width of the nasal valve can be increased using spreader grafts and flaring sutures.

The internal nasal anatomy also includes specialized structures such as agger nasi cells, located anterior to the middle turbinate. These are parts of the anterior ethmoid air cells and the uncinate process, a thin crescent-shaped bone that contributes to sinus drainage pathways by protecting the infundibulum from inhaled particles. [15]

Nasal Analysis

The nose can be conveniently divided into several subunits: the dorsum, sidewalls (paired), hemilobules (paired), soft triangles (paired), alae (paired), and columella (see the image below). Viewing the external nasal anatomy by its subunits is important because defects that span an entire subunit are usually repaired with reconstruction of that subunit.

Burget suggests replacement of the entire subunit if more than 50% of the subunit is lost during resection. [16] Aesthetically, the nose — from the nasion (nasofrontal junction) to the columella-labial junction — ideally occupies one third of the face in the vertical dimension. From ala to ala, it should ideally occupy one fifth of the horizontal dimension of the face.

The nasofrontal angle between the frontal bone and nasion is usually 120° and slightly more acute in males than in females. The nasofacial angle, or the slope of the nose compared with the plane of the face, is approximately 30-40°. The nasolabial angle between the columella and philtrum is about 90-95° in males and 100-105° in females.

On profile view, normal columella show, i.e., the height of the nasal aperture visible, is 2-4 mm. The dorsum should be straight. From below, the alar base forms an isosceles triangle, with the apex at the infratip lobule just beneath the tip. Appropriate projection of the nasal tip, or the distance of the tip from the face, is judged using the Goode rule. The tip projection should be 55-60% of the distance between the nasion and tip-defining point. A columellar double break may be present, marking the transition between the intermediate crus of the lower lateral cartilage and the medial crus.

Studies emphasize systematic approaches such as the "10-7-5 Method," which evaluates nasal proportions across frontal, lateral, and basal views. This method provides a structured framework for assessing: [17]

-

Facial symmetry and proportions

-

Nasal angles (nasofrontal, nasolabial, and nasofacial)

-

Tip rotation, projection, and alar-columellar relationships

-

Nostril shape and symmetry

These detailed analyses ensure that both functional and aesthetic goals are met during rhinoplasty or reconstructive procedures.

-

Nasal embryology.

-

Nasal anatomy.

-

Nasal anatomy. Image used with permission.

-

Nasal anatomy, base. Image used with permission.

-

The quadrangular cartilage, the vomer, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and aspects from the premaxilla and palatine bones form the nasal septum.

-

Nasal scroll.

-

Nasal subunits include the dorsum, sidewalls, lobule, soft triangles, alae, and columella.