Overview

The vestibular system, which is the system of balance, consists of five distinct end organs: three semicircular canals that are sensitive to angular accelerations (head rotations) and two otolith organs (the utricle and the saccule) that are sensitive to linear (or straight-line) accelerations. [1] Together, these structures detect angular and linear accelerations of the head, enabling coordination of posture, gaze stabilization, and equilibrium. [2]

The semicircular canals are arranged as a set of three mutually orthogonal sensors; that is, each canal is at a right angle to the other two. This is similar to the way the three sides of a box meet at each corner and are at a right angle to one another. Furthermore, each canal is maximally sensitive to rotations that lie in the plane of the canal. The result of this arrangement is that three canals can uniquely specify the direction and amplitude of any arbitrary head rotation. The canals are organized into functional pairs, wherein both members of the pair lie in the same plane. Any rotation in that plane is excitatory to one of the members of the pair and inhibitory to the other.

The otolith organs include the utricle and the saccule. The utricle senses motion in the horizontal plane (e.g., forward-backward movement, left-right movement, or a combination thereof). The saccule senses motions in the sagittal plane (e.g., up-down movement; see the images below).

The vestibular system functions synergistically with visual and proprioceptive inputs to ensure accurate spatial awareness and motor coordination. Damage to any component can result in vertigo, disequilibrium, or other balance disorders. [2]

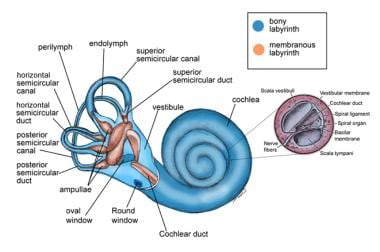

Membranous Labyrinth

The membranous labyrinth is a delicate, interconnected structure housed within the bony labyrinth of the inner ear. [2] The membranous labyrinth is surrounded by perilymph and suspended by fine connective tissue strands from the bony labyrinth. This system is essential for both auditory and vestibular functions and is filled with endolymph, a potassium-rich fluid essential for sensory transduction. [3]

It consists of an anterior chamber and the cochlear duct, which subserves hearing and connects by way of the round saccule with the peripheral vestibular apparatus. The peripheral vestibular apparatus consists of the saccule, utricle, and semicircular canals.

Saccule

The saccule is an almost globular-shaped sac that lies in the spherical recess on the medial wall of the vestibule. The saccule is particularly sensitive to linear acceleration of the head in the vertical plane. It is, therefore, a major gravitational sensor when the head is in an upright position. [4] It is connected anteriorly to the cochlear duct by the ductus reuniens and posteriorly to the endolymphatic duct via the utriculosaccular duct. The saccular macula is an elliptical thickened area of sensory epithelium that lies on the anterior vertical wall of the saccule. This macula contains specialized hair cells topped with stereocilia and a single kinocilium, which are embedded in a gelatinous otolithic membrane. The otolithic membrane is weighted with calcium carbonate crystals called otoconia, enhancing its sensitivity to gravitational forces and inertial changes. Movement or tilt of the head causes displacement of this membrane, bending the stereocilia and triggering nerve impulses via the saccular branch of the inferior vestibular nerve. [5, 6]

The membranous saccule closely conforms to its bony housing within the vestibule. It is bounded medially and inferiorly by the spherical recess, laterally by perilymph, and superiorly by structures such as the crista vestibuli. Its proximity to other vestibular structures such as the utricle and semicircular canals ensures integrated sensory input for balance and spatial orientation. [7]

Utricle

The utricle is larger than the saccule and lies posterosuperiorly to it in the elliptical recess of the medial wall of the vestibule. It is connected anteriorly via the utriculosaccular duct to the endolymphatic duct. [8]

The three semicircular canals open into it by means of five openings; the posterior and the superior semicircular canals share one opening at the crus commune.

The macula of the utricle lies mainly in the horizontal plane and is located in the utricular recess, which is the dilated anterior portion of the utricle. This orientation allows the utricle to detect linear accelerations and head tilts in the horizontal plane. [5]

Semicircular canals

The semicircular canals are located within the bony labyrinth of the petrous temporal bone. [9] The three semicircular canals are small, ringlike structures: lateral or horizontal, superior or anterior, and posterior or inferior (see the image below). They are oriented at right angles to each other and are situated so that the superior and posterior canals are at 45° angles to the sagittal plane and the horizontal canal is 30° to the axial plane. Each canal is maximally responsive to angular motion in the plane in which it is situated and is paired with a canal on the contralateral side so that stimuli that are excitatory to one are inhibitory to the other.

The horizontal canal is paired with the contralateral horizontal canal; however, the superior canal is paired with the contralateral posterior canal and vice versa. Each canal forms two thirds of a circle with a diameter of about 6.5 mm and a luminal cross-sectional diameter of 0.4 mm. One end of each canal is dilated to form the ampulla, which contains a saddle-shaped ridge termed the crista ampullaris; the sensory epithelium lies on the crista ampullaris. The crista ampullaris comprises hair cells embedded in a gelatinous structure called the cupula. Movement of endolymph within the canals during angular acceleration deflects the cupula, bending stereocilia on the hair cells. [10] This mechanical deformation generates neural signals transmitted via the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) to the brain. [5] The nonampulated ends of the superior and posterior canal form the crus commune or common crus. All canals merge into the utricle.

Vestibular Sensory Epithelium

The vestibular sensory epithelium is located on the maculae of the saccule and utricle and the cristae of the semicircular canals. The sensory cells are surrounded by supporting cells; therefore, they do not come into direct contact with the bony base of the cristae.

Macula

Each macula is a small area of sensory epithelium. The ciliary bundles of the sensory cells project into the overlying statoconial membrane, which consists of three layers, as follows:

-

Calcareous particles (otoconia) - Inorganic crystalline deposits composed of calcium carbonate or calcite. The otoconia, in the first layer, are distributed in a characteristic pattern and vary in size from 0.5 to 30 metric circular mils or mcm, with most being about 5-7 mcm. The otoconia seem to have a slow turnover. They appear to be produced by the supporting cells of the sensory epithelium and to be resorbed by the dark cell region. The specific gravity of the otolithic membrane is much higher than that of the endolymph, about 2.71-2.94, facilitating its function in detecting head movements relative to gravity. [11]

-

A gelatinous area of mucopolysaccharide gel that embeds the otoconia [5]

-

Subcopula meshwork is a fibrous network providing structural support. [5]

On a morphologic basis, each macula can be divided into two areas by a narrow, curved zone that extends through its middle. This zone has been termed the striola. It forms an axis of mirror symmetry such that hair cells on opposite sides of the striola have opposing morphological polarization. The striola has type I hair cells innervated by calyceal nerve endings and a subtype of type II hair cells located along the line of polarity reversal. [12]

Crista

The crista ampullaris consists of a crest of sensory epithelium supported on a mound of connective tissue, lying at right angles to the longitudinal axis of the canal. This arrangement allows detection of angular accelerations. [7]

A bulbous, wedge-shaped, gelatinous mass called the cupula surmounts the crista. Cilia of the sensory cells project into the cupula. The cupula extends from the surface of the cristae to the roof and lateral walls of the membranous labyrinth, forming a fluid-tight partition. Angular head movements cause deflection of the cupula due to endolymph inertia, stimulating hair cell mechanoreceptors. [13]

Studies have highlighted key molecular players involved in vestibular function:

Otopetrin-1 (OTOP1): It is essential for otolith development through calcium regulation and protein secretion. OTOP1 mutations lead to absent or dysfunctional otoconia, impairing balance. [14]

Otoconin-90 (OC90): OC90 is a critical matrix protein for otolith formation, contributing to crystal size regulation and polymorph selection. [14]

Retinoic acid (RA): RA degradation mediated by CYP26B1 is crucial for striolar zone development during embryogenesis. [15]

Vestibular Receptor Cells

Vestibular hair cells

The vestibular hair cells, essential for detecting head movements and maintaining balance, [16] can be classified as type I or type II. These hair cells are located in the sensory epithelia of the vestibular system, including the maculae (utricle and saccule) and cristae ampullaris (within the semicircular canals). They convert mechanical stimuli into neural signals. [16]

Type I hair cells correspond to the inner hair cells of the organ of Corti and are shaped like ancient Greek wine bottles, with round bottoms, thin necks, and wider heads. Each cell is surrounded by a nerve chalice from one of the terminal branches of a thick or medium nerve fiber of the vestibular nerve. Occasionally, 2-3 hair cells may be included in the same nerve chalice. Type I hair cells exhibit unique ionic currents, including low resting membrane potentials. They are particularly suited to detect high-frequency head accelerations. [17] These cells are predominantly located in the central zones of the sensory epithelia, such as the striola of the maculae and the central regions of the cristae ampullaris. [18]

Type II hair cells correspond to the outer hair cells of the organ of Corti and are shaped like cylinders, with a flat upper surface covered by a cuticle. They are innervated by multiple bouton terminals of vestibular primary afferents. [19] Type II hair cells have distinct ionic currents and are involved in encoding lower-frequency head movements. They also play a role in maintaining baseline activity within the vestibular system. These cells are more evenly distributed across both peripheral and central zones of the sensory epithelia. [18]

Both types of hair cells possess stereocilia on their apical surfaces, which are deflected in response to mechanical forces generated by head movements. This deflection modulates neurotransmitter release at the basal synapses, thereby conveying information about head position and motion to the brain via the vestibular nerve. [20]

Sensory cells

The sensory cells are neuroepithelial hair cells. Each bears 50-100 stereocilia and a single long, thick kinocilium on the apical surface.

Stereocilia

The stereocilia, which are nonmotile and rigid, are not true cilia but instead consist of actin filaments in a paracrystalline array with other cytoskeletal proteins. The actin filaments in the stereocilia extend into the hair cell and are anchored in a thickened region near the apical surface, termed the cuticular plate. The cuticular plate is a dense, filamentous meshwork of randomly oriented actin filaments that fills up the area just under the apical surface of the cell. The stereocilia vary in height but are graded with reference to the kinocilium in a staircase arrangement, the tallest being close to the kinocilium.

Kinocilium

The kinocilium projects from the cell cytoplasm through a segment of the cell lacking a cuticular plate. The kinocilium has a complete structure of a motile cilium with a basal body, which closely resembles the centriole and the 9+2 arrangement of microtubule doublets of true cilia. However, the inner dynein arms are lacking, and a central pair of microtubules is not present in the distal portion of the kinocilium, suggesting that the vestibular kinocilia may be immotile or only weakly motile. Each hair cell is morphologically polarized with respect to location of the kinocilium. In the utricular macula, the hair cells are found to be polarized with the kinocilium facing the striola, whereas in the saccular macula, the kinocilium of each cell faces away from the striola.

Supporting cells

Supporting cells that extend from the basement membrane to the apical surface surround hair cells. Their nuclei are usually found just above the basement membrane and below the hair cells. Hair cells form tight junctions and desmosomes with the supporting cells, thus separating the endolymphatic space in which endolymph bathes the stereocilia above the cells, from the perilymphatic space below the apical surface.

Innervation

Innervation of the two types of hair cells is different from one another. The basal portions of the cells synapse with afferent and efferent nerve fibers. A chalice formed by a single afferent nerve that makes 10-20 synapses surrounds each type I cell. Type II cells have multiple bouton-type afferent nerve terminals. The efferent nerve endings have small homogenous vesicles in the neuroplasm and synapse by en passant endings on type II hair cells, afferent boutons, calyciform terminals, and afferent nerve fibers.

Afferent vestibular pathways

The primary vestibular neurons are bipolar neurons whose cell bodies make up the Scarpa's ganglion in the internal auditory canal. These bipolar neurons lie in two linearly arranged cell masses extending in a rostral-caudal direction in the internal auditory canal. Each neuron consists of a superior and inferior cell group related to superior and inferior divisions of the vestibular nerve trunk.

The superior division supplies the cristae of the superior and lateral canals, the macula of the utricle, and the anterosuperior part of the macula of the saccule. The inferior division supplies the crista of the posterior canal and the main portion of the macula of the saccule. Medial to the vestibular ganglion, the nerve fibers of both divisions merge into a single trunk, which enters the brainstem.

The superior division of the vestibular nerve has large nerve fibers, which arise mainly from ganglion cells in the rostral part of the ganglion, and small fibers that originate mainly in the caudal portion of the ganglion. The ampullary nerves pass in the rostral part of the nerve trunk. Large fibers become concentrated in the central parts of these nerve branches and are surrounded by the small fibers. This arrangement persists into the cristae, with the large fibers more numerous at the crests and the small fibers more numerous at the slopes of the cristae. The large fibers appear to end predominantly in the large, chalice-type endings on type I hair cells, whereas the small fibers make contact with the type II hair cells. The population of large fibers is greater in the striola of both maculae where a predominance of type I hair cells exists.

Central Vestibular Connections

Vestibular nuclei

Most afferent fibers from the hair cells terminate in the vestibular nuclei, which lie on the floor of the fourth ventricle. They are bound medially by the pontine reticular formation, laterally by the restiform body, rostrally by the brachium conjunctivum, and ventrally by the nucleus and spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve. The central processes of the primary afferent vestibular neurons divide into an ascending and descending branch after entering the brainstem at the inner aspect of the restiform body. Some primary vestibular neurons pass directly to the cerebellum, in particular the flocculonodular lobe and the vermis. No primary vestibular afferent neurons cross the midline.

In the vestibular nuclei, four major groups of cell bodies (the second-order vestibular neurons) may be identified: [2]

-

Superior vestibular nucleus (SVN) (Bechterew's nucleus) - Located in the dorsolateral pons, the SVN primarily receives input from the semicircular canals and plays a crucial role in coordinating eye movements to stabilize vision during head motion through the vestibulo-ocular reflex.

-

Lateral vestibular nucleus (LVN) (Dieter's nucleus) - It is situated ventrolateral to the upper portion of the medial nucleus, just above the inferior nucleus and ascends almost to the level of the abducens nucleus. It is the origin of the lateral vestibulospinal tract, which descends ipsilaterally to facilitate extensor muscle tone, thereby contributing to the posture and balance by influencing limb extensor muscles.

-

Medial vestibular nucleus (MVN) (Schwalbe's nucleus) - Found in the medulla, the largest of the four, the MVN gives rise to the medial vestibulospinal tract, projecting bilaterally to cervical spinal cord levels. It is essential for head and neck stabilization via the medial vestibulospinal tract.

-

Descending vestibular nucleus (DVN) - Also located in the medulla, the DVN integrates inputs from the vestibular apparatus and the cerebellum, contributing to the modulation of vestibulospinal reflexes and balance control.

Some nuclei receive only primary vestibular afferents, but most receive afferents from the cerebellum, reticular formation, spinal cord, and contralateral vestibular nuclei.

Macular afferents

The ascending ramus of utricular fibers terminates richly on cells throughout the ventral one third of the LVN; some of these pass on medially to terminate on large cells in the rostral one half of the MVN. The descending ramus of utricular fibers terminates on cells (medium and large) in the rostral one third of the DVN.

Some of the ascending branches of the saccule innervate a small area in the LVN. The descending ramus of saccular nerves end on the same cells in the rostral one third of the descending nucleus as utricular and canal fibers.

Semicircular canals afferents

The ascending branches of the fibers from the superior and lateral canals terminate in the rostral part of the SVN in a distribution of large and small fibers.

After giving off long collaterals in the nucleus, the ascending branches continue directly to the cerebellum. The incoming fibers from the posterior canal crista bifurcate more medially, and the ascending branches end in a more central and medial region of the SVN and probably continue to the cerebellum.

The descending branches of fibers from the three cristae give collaterals mainly to the MVN and, to a lesser extent, to the lateral and descending vestibular nuclei.

Projections From the Vestibular Nuclei

The projections from the vestibular nuclei are fairly well known. These projections extend to the cerebellum, extraocular nuclei, and spinal cord. The cells of the SVN project in an ascending direction to the nuclei of the extraocular muscles (III and IV). This projection almost, if not entirely, reaches the ipsilateral eye nuclei by way of the medial longitudinal fasciculus.

The LVN has been shown to be the sole source of fibers to the vestibulospinal tract. These fibers terminate near the anterior horn cells of all the spinal cord levels and mediate trunk and limb muscle reflexes.

The DVN appears to be the nucleus most clearly related to the cerebellum. The MVN appears to be the least specialized of the complex. It receives afferents from the semicircular canals and utricle; its projections are ascending and descending in the medial longitudinal fasciculus. The ascending ones course bilaterally to the extraocular muscles, and the descending ones course to the cervical segment of the cord.

The vestibular area in the cerebral cortex has not been defined by using anatomical methods. Electrophysiologic studies indicate that the projection area is in the temporal lobe near the auditory cortex. Functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography scanning studies implicate the insula as another possible cortical projection of the vestibular system. [21]

The Labyrinthine Fluid

The labyrinth contains two distinctly separate fluids: endolymph and perilymph. They do not mix.

Endolymph

Among the extracellular fluids of the body, endolymph has a unique ionic composition. The sodium (Na+) content is low and the potassium (K+) content is high, which causes endolymph to resemble intracellular, rather than extracellular, fluid. This distinctive composition is crucial for generating the electrochemical gradients necessary for sensory transduction in hair cells. [22]

Endolymph is believed to be produced by the dark cells of the cristae and maculae, which are separated by a transitional zone from the neuroepithelium. These cells utilize selective ion transport mechanisms to maintain the high potassium-to-sodium ratio. [23]

The site of absorption of endolymph is presumably the endolymphatic sac, which is connected to the utricle and saccule by means of the endolymphatic, utricular, and saccular ducts. Experimental blockage of the endolymphatic duct produces endolymphatic hydrops, further suggesting that the endolymphatic sac is the primary site of absorption.

Perilymph

Perilymph fills the space between the bony and membranous labyrinths. [2] The ionic composition of perilymph is similar to that of extracellular fluid and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The site of perilymph production is controversial — it might be an ultrafiltrate of blood, CSF, or both. Perilymph leaves the ear by draining through venules and through the middle ear mucosa.

The separation between endolymph and perilymph is important for maintaining the electrochemical environment required for hair cell depolarization during sensory transduction. Movements of these fluids relative to hair cells in the vestibular apparatus (utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals) facilitate the detection of head motion and spatial orientation. [2]

Blood Supply to the Vestibular End Organ

The main blood supply to the vestibular end organs is through the labyrinthine (internal auditory) artery, which usually arises from the basilar artery, but can originate from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Shortly after entering the inner ear, the labyrinthine artery divides into two branches, known as the anterior vestibular artery and the common cochlear artery.

The anterior vestibular artery provides the blood supply to most of the utricle, to the superior and horizontal ampullae, and to a small portion of the saccule. The common cochlear artery forms two divisions, called the proper cochlear artery and the vestibulocochlear artery. The vestibulocochlear artery divides into a cochlear ramus and a vestibular ramus (also known as the posterior vestibular artery), which provide the blood supply to the posterior ampulla, major part of the saccule, parts of the body of the utricle, and the horizontal and superior ampullae.

-

Anatomy of the labyrinth.

-

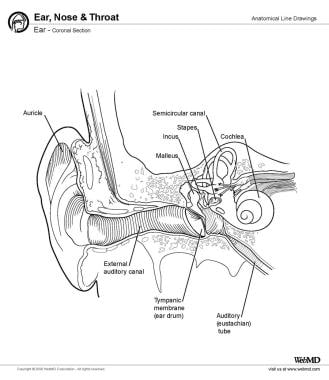

Ear, coronal section.

-

Anatomy of the vestibular system. (Courtesy of Hamid R Djalilian, MD)