Overview

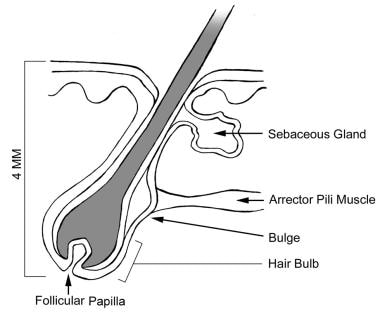

The human hair follicle is an intriguing structure, and much remains to be learned about hair anatomy and its growth. The hair follicle can be divided into three regions: the lower segment (bulb and suprabulb), the middle segment (isthmus), and the upper segment (infundibulum).

The lower segment extends from the base of the follicle to the insertion of the erector pili muscle (also known as the arrector pili muscle). The bulb houses the dermal papilla, a cluster of inductive mesenchymal cells required for hair follicle growth in each cycle. Surrounding the dermal papilla is the hair matrix, composed of rapidly proliferating keratinocytes and melanocytes, which give rise to the hair shaft and its pigmentation. [1, 2]

The middle segment is a short section that extends from the insertion of the erector pili muscle to the entrance of the sebaceous gland duct. The bulge area is marked by the arrector pili muscle insertion. It houses epidermal stem cells, which are essential for hair follicle regeneration and wound healing. [3]

The upper segment extends from the entrance of the sebaceous gland duct to the follicular orifice. [4, 5] The infundibulum serves as a conduit for the sebum and cellular debris to reach the skin surface. [3] (See the image below.)

The hair follicle's structure includes both epithelial and mesenchymal components. The outer root sheath (ORS) is contiguous with the epidermis and provides structural support, while the inner root sheath (IRS) molds the developing hair shaft and consists of Henle's layer, Huxley's layer, and the cuticle. The dermal sheath, derived from the dermis, envelops the follicle, offering additional support. [6]

The histological features of the hair follicle change continuously and considerably during the hair growth cycle, thereby making follicular anatomy an even more complex entity.

The size of hair follicles varies considerably during the existence of the follicles. Anagen hairs vary in size from large terminal hairs, such as those on the scalp, to the small vellus hairs that cover almost the entire glabrous skin (except palms and soles). Under hormonal influences, the vellus hair follicles in the male beard area usually thicken and darken at puberty. In individuals who are predisposed to hair loss, the terminal hairs on the adult scalp can undergo involutional miniaturization (become vellus).

Although vellus hairs greatly outnumber terminal hairs, the latter are more important. Therefore, the discussion on hair anatomy in this article focuses on terminal hairs.

The follicular life cycle can be divided into four phases: anagen, catagen, telogen, and exogen. During anagen, active proliferation occurs in the matrix, leading to hair shaft formation. Catagen marks a phase of controlled involution during which mitotic activity of the germinal matrix ceases, the base of the hair condenses into a club that moves upward to the level of the arrector pili muscle, and the whole inferior segment of the follicle degenerates. Telogen is a resting phase during which club hairs remain anchored until exogen facilitates their shedding. [7]

In the human scalp, the anagen phase lasts approximately 3-4 years, the catagen phase lasts about 2-3 weeks, and the telogen phase lasts approximately 3 months. Approximately 84% of scalp hairs are in the anagen phase, 1-2% are in the catagen phase, and 10-15% are in the telogen phase.

The follicular life cycle is regulated by intricate molecular signaling pathways between dermal papilla cells and epithelial stem cells located in the bulge region. These signals orchestrate processes such as induction, organogenesis, cytodifferentiation, and regeneration. The bulge region serves as a reservoir of multipotent stem cells that contribute to follicular regeneration during each cycle. [8]

Techniques for studying hair microanatomy include the following:

-

Hair clipping - Performed close to the surface of the scalp

-

Gentle hair pull

-

Aggressive hair pluck (trichogram)

-

Scalp biopsy - Possible use of light microscopy or scanning electron microscopy to study scalp tissue

Microanatomy of Anagen Phase Hair

The bulb encompasses the dermal papilla and the hair matrix. The dermal papilla consists of an egg-shaped accumulation of mesenchymal cells surrounded by ground substance that is rich in acid mucopolysaccharides (AMPs). The papilla protrudes into the hair bulb and is responsible for instigating and directing hair growth.

Because of the abundance of AMPs, dermal papilla stains positively with Alcian blue and metachromatically with toluidine blue. The lower part of the dermal papilla is connected to the fibrous root sheet.

The hair matrix surrounds the top and sides of the dermal papilla. The hair matrix is the actively growing portion of the follicle consisting of a collection of epidermal cells that rapidly divide, move upward, and give rise to the hair shaft and the internal root sheath. The cells of the hair matrix have vesicular nuclei and deeply basophilic cytoplasm. Melanocytes can be found between the basal cells of the hair matrix, where they synthesize melanin and transfer it to keratinocytes in the developing hair shaft. The amount and type of melanin determine hair color, with darker pigmentation associated with higher concentration of melanin pigment within the melanocytes. [9]

The hair matrix cells give rise to six different types of cells that make up the different layers of the hair shaft (medulla, cortex, and cuticle) and the IRS. These layers undergo keratinization as they move upward from the matrix. The dermal papilla also regulates follicular cycling by influencing epithelial-mesenchymal interactions critical for transitioning between anagen (growth), catagen (regression), and telogen (resting) phases. [10]

Inner root sheath

The IRS is closely apposed to the hair shaft, and because the sheath contains no pigment, it can easily be distinguished from the hair shaft. The IRS coats and supports the hair shaft up to the level of the isthmus, at which it breaks down and exfoliates in the infundibular space.

The IRS consists of three concentric layers: Henle's layer (outermost), Huxley's layer (middle), and the IRS cuticle (innermost). These layers are derived from matrix cells in the follicular bulb and play essential roles in hair formation, protection, and keratinization: [11]

-

Henle's layer - The outermost layer, composed of a single layer of cuboidal cells, is the first to keratinize. Its smooth interface with the ORS facilitates movement of the IRS against surrounding structures. This early keratinization process contributes to the structural integrity of the developing hair.

-

Huxley's layer - Situated between Henle's layer and the IRS cuticle, this layer has a thickness of 2-4 cells and contains numerous trichohyalin granules. These granules are essential for keratinization, providing mechanical strength through cross-linking keratin filaments.

-

IRS cuticle - The innermost layer; its cells interlock with those of the hair cuticle to ensure proper adhesion and alignment during growth. This integration is crucial for shaping and supporting the hair shaft as it grows.

The layers keratinize by forming trichohyalin granules; this is unlike the hair shaft, which undergoes trichile shaping and supports the hair fiber as it grows. The outermost layer of the IRS (Henle's layer) keratinizes first because it is lowest in the hair follicle. The cells of the innermost layer (IRS cuticle) point downward and inward and interconnect with those of the hair cuticle. These two cuticles are completely integrated and keratinize after Henle's layer. The middle layer (Huxley's layer) keratinizes after the IRS cuticle and the hair cuticle.

The three layers are distinct just above the dermal papilla. However, they keratinize relatively low in the hair follicle and are indistinguishable at higher levels, where they function as a single unit covering the hair shaft. The IRS serves as a rigid, cornified sleeve that molds and protects the growing hair shaft. Its keratinized structure ensures mechanical stability, while its intimate connection with the hair cuticle facilitates synchronized growth through the follicular canal. Additionally, it provides a barrier function, shielding developing hair from external damage. [11] The IRS stains deeply with toluidine blue because of the presence of the amino acid citrulline.

Hair shaft

The hair shaft consists of three layers — the cuticle, cortex, and medulla — each contributing distinct properties to the hair.

The outermost layer of the hair shaft (cuticle) consists of overlapping cells that are arranged like shingles. They point outward and upward and interlock with the IRS cuticle, which leads to a firm attachment between the hair shaft and the IRS. As a result, they move upward in the follicular canal as a single unit. The cuticle primarily protects the inner layers of the hair from physical and chemical damage. It also provides mechanical strength and resistance to abrasion. [12]

The middle layer of the hair shaft (hair cortex) constitutes the bulk of the hair shaft and is responsible for its strength, elasticity, and color. It is composed of elongated keratinized cells containing hard keratin intermediate filaments stabilized by inter- and intra-molecular disulfide bonds. These bonds provide tensile strength and flexibility. The cortex also houses melanin granules, which determine the hair color. [12] Unlike the IRS, which keratinizes by forming trichohyalin granules (soft keratin), the hair cortex cells keratinize without forming granules (the aforementioned trichilemmal keratinization). The keratin produced is termed as hard keratin.

The innermost layer (medulla) is frequently difficult to visualize. Routine light microscopy is typically used to visualize this layer because it is discontinuous in many cases and is often completely absent. Medullary cells contain glycogen-rich vacuoles and medullary granules, which contain citrulline (similar to the cells of the IRS).

Outer root sheath

The ORS covers the IRS as it extends upward from the matrix cells at the lower end of the hair bulb to the entrance of the sebaceous gland duct. It is thinnest at the level of the bulb and thickest in the middle portion of the hair follicle, where it harbors lineage-specific stem cells for hair follicle regeneration. [13] The ORS cells contain clear, vacuolated cytoplasm because of the presence of large amounts of glycogen.

The ORS does not keratinize below the level of the isthmus (in contrast to the IRS). However, at the level of the isthmus where the IRS disintegrates, it keratinizes without forming granules (trichilemmal keratinization), which is similar to the keratinization of the hair cortex.

At the level of the infundibulum, keratinization of the ORS changes to normal epidermal keratinization, with formation of the granular cell layer and stratum corneum. The basal cell layer of the ORS contains inactive amelanotic melanocytes; in contrast, the surface epidermis that lines the infundibulum contains active pigmented melanocytes. The inactive melanocytes in the basal cell layer can become melanin-producing cells after skin injury (e.g., chemical peels, laser resurfacing, dermabrasion). They proliferate and migrate toward the regenerating upper portion of the ORS and the epidermis.

The ORS serves as a reservoir for epithelial stem cells that are crucial for epidermal regeneration during wound healing. These stem cells can migrate out of the follicle to repopulate damaged areas of skin. The mid-ORS region has been identified as particularly rich in lineage-specific stem cell markers, such as CD34 and nestin, which contribute to its regenerative potential. [13, 14]

During wound healing, ORS cells can transition to an interfollicular epidermal phenotype, demonstrating their plasticity and potential for tissue repair. This layer also plays a role in anchoring the hair follicle within the dermis and contributes to follicular cycling by interacting with other follicular structures such as the dermal papilla. [13, 14, 15]

Glossy (vitreous) layer

The glossy (vitreous) layer is the eosinophilic acellular zone surrounding the ORS. This layer is continuous with the epidermal basement membrane and is similarly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant. Unlike the epidermal basement membrane, the glossy layer is much thicker and is visible with routine stains.

The glossy layer undergoes dynamic morphological changes during the hair cycle. In the anagen phase, it appears thin and inconspicuous. During the catagen phase, it thickens markedly. As the follicle progresses through late catagen, apoptotic processes lead to pleating and corrugation of this layer, a hallmark feature of this transitional phase. These pleated structures enclose atrophying cells in the lower part of the follicle. By telogen, the glossy layer becomes fragmented and resorbed in areas undergoing cyclic changes, while remaining unchanged in regions such as the upper follicle that do not experience such transformations. [16]

Histological studies have revealed additional structural complexities within the glossy layer. It comprises three ultrastructural components: an inner fibrillar tangle interdigitating with serrations of ORS cells, a thin membrane that cannot be stained, and an outer PAS-positive hyaline membrane. Morphological variations such as folds or protrusions into the ORS have also been observed. These folds can be unilateral, bilateral, or circular and are thought to serve as interdigitations or adaptations to mechanical stress during hair growth cycles. [16]

Fibrous root sheath

The fibrous root sheath is the outermost layer of the hair follicle and surrounds the vitreous layer. It consists of thickened collagen bundles that coat the entire hair follicle. The root sheath is continuous with the dermal papilla at its lower end and with the papillary dermis above it.

Suprabulb region

The suprabulb region extends from the hair bulb to the isthmus and consists of components of the hair shaft, IRS, ORS, vitreous layer, and fibrous root sheath. During the anagen phase, active proliferation occurs in this region, contributing to hair growth. [1]

Isthmus

The isthmus is the shortened segment of the hair follicle, extending from the attachment of the erector pili muscle (bulge region) into the entrance of the sebaceous gland duct. At this level, the IRS fragments and exfoliates, and the ORS is fully keratinized (trichilemmal keratinization). The bulge region is difficult to visualize on routine stains. It is made up of several protrusions and crests and contains cells with pluripotent capabilities.

Infundibulum

The infundibulum is the upper portion of the hair follicle, above the entry of the sebaceous duct. Surface epidermis lines the infundibulum. This segment serves as an interface between skin epithelium and external environments. It plays a significant role in immune defense and is implicated in various skin disorders such as acne and infundibular folliculitis. [17]

Microanatomy of Catagen Phase Hair

Although the factors are largely unknown, active hair growth (i.e., the anagen phase) halts, and the catagen phase begins. A period of 2-3 weeks is required for the transition to occur.

During this next phase, the hair bulb becomes keratinized (club hair) and is pushed upward to the surface by a column of epithelial cells. This column of cells is characteristically thick and corrugated in this stage, eventually shortening progressively from its lower end.

Apoptosis occurs in the epithelial cells of the hair matrix and ORS, leading to follicular shrinkage. The lower two thirds of the follicle, including the matrix and inferior segment, regresses and disappears. [8] It is reduced to a small, nipple-like configuration termed as the secondary follicular germ.

In this stage, the dermal papilla moves upward, following the epithelial sac. This migration is essential for maintaining cyclic hair growth. If the dermal papilla fails to reach its position beneath the bulge, hair cycling may terminate, resulting in hair loss. Melanin production also halts during catagen, and melanocytes within the follicle may undergo apoptosis. This contributes to changes in pigmentation during this phase. [8]

Microanatomy of Telogen Phase Hair

During the telogen (resting) phase, the hair follicle enters a state of relative proliferative quiescence but remains metabolically active. The secondary follicular germ and the dermal papilla form the telogen germinal unit, from which the new anagen hair develops.

This phase is characterized by dynamic molecular and cellular activities, contrary to earlier beliefs that telogen is a dormant stage. Studies have revealed that telogen hair follicles prepare for regeneration by modulating signaling pathways such as bone morphogenic protein (BMP), Wnt, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). For instance, FGF18 signaling has been shown to maintain telogen refractivity, while TGF-β2 signaling counteracts this effect, promoting anagen initiation through paracrine interactions between dermal papillae and hair germ progenitors. Telogen can be divided into two sub-stages: early "refractory" telogen, marked by BMP-mediated inhibition of hair growth, and late "competent" telogen, where pro-regenerative signals dominate. The transition from late telogen to anagen involves suppressing molecular brakes on hair growth while activating regenerative pathways. [18] Some authors believe that cells (with pluripotent potential) residing in the bulge region are responsible for regenerating new hairs. [19] The telogen germinal unit, unlike the primary prenatal follicular germ unit, does not need to regenerate adnexal structures such as the sebaceous and apocrine glands and their corresponding ducts. [20]

-

Anatomy of the hair follicle.