Practice Essentials

A quarter of all extranodal lymphomas occur in the head and neck, and 8% of findings on supraclavicular fine-needle aspirate biopsy yield a diagnosis of lymphoma. Lymphoma is the second most common primary malignancy occurring in the head and neck. Nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy, fine-needle aspiration cytology, excision lymph-node biopsy (in Hodgkin lymphoma [HL] and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [NHL]), and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are essential in the workup of patients with head and neck lymphomas. ABVD, a regimen of doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine, is considered the standard of care in HL

Treatment for NHL is based on the type of disease and involves combination therapy or targeted therapies derived from the immunohistochemistry of the tumor. Radiation is frequently used in the treatment of HL and NHL.

Risk factors for HL include immunodeficiency and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) exposure. Risk factors for NHL include immunodeficiency, exposures to chemicals such as glyphosate (eg, Roundup weed killer), [1] radiation treatment or chemotherapy, and infections with EBV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus, Helicobacter pylori, human T-lymphotropic virus 1, or human herpesvirus 8. Patients with HL have a bimodal age distribution, whereas patients with NHL are usually older than 60 years.

See the image below.

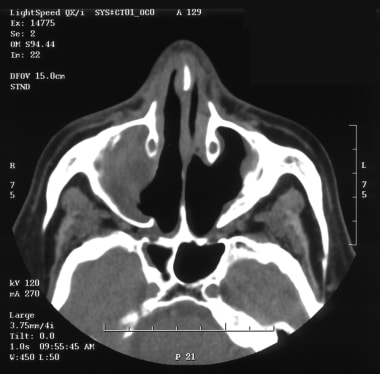

CT scan of a patient with a natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma of the right nasal cavity and maxillary sinus.

CT scan of a patient with a natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma of the right nasal cavity and maxillary sinus.

Signs and symptoms

Lymphoma may be nodal or extranodal. Common symptoms include the following:

-

Nodal presentation of HL - 1 or more small-to-medium, rubbery lymph nodes in the neck, which may wax or wane in size but grow over time

-

NHL - Mass in the oropharynx or nasopharynx

-

Extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type - Ulcerative destructive lesion of the nose, sinuses, and face

-

Lymphoma in the thyroid - Neck swelling, hoarseness, dysphagia, or neck pressure/tenderness

-

Constitutional symptoms (B symptoms) - These may occur in up to one third of patients with lymphoma

Full otorhinolaryngologic and neck examination, including fiberoptic examination, in addition to complete physical examination, is indicated. Physical findings that may be noted include the following:

-

Painless or mildly tender peripheral adenopathy in cervical, axillary, inguinal, and femoral regions

-

Superior vena cava syndrome and pleural effusions (from a mediastinal mass)

-

A large, asymptomatic abdominal mass in some patients with indolent NHL

See Presentation for more details. See also 10 Patients with Neck Masses: Identifying Malignant versus Benign, a Critical Images slideshow, to help identify several types of masses.

Diagnosis

The following laboratory studies may be warranted:

-

Complete blood count

-

Serum chemistries (including calcium, phosphate, and uric acid)

-

Liver function tests (including measurement of lactate dehydrogenase)

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (in HL)

-

HIV and hepatitis B and C viral panels (encouraged)

-

Pregnancy test in females of childbearing age

The following imaging studies may be warranted:

-

Chest radiography (essential)

-

Computed tomography (CT) scanning with contrast enhancement of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis (necessary for mediastinal, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric adenopathy)

-

CT scanning of the head and neck (mandatory for a head and neck presentation; localized disease; or cranial neuropathies, hearing loss, vertigo, or visual changes)

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; indicated for evaluating the brain or spinal cord)

-

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning

Other tests to be considered include the following:

-

Immunohistochemical analysis of the tumor (essential)

-

Cytogenetic analysis (useful in select cases)

-

Polymerase chain reaction analysis

-

Fluorescent in-situ hybridization

-

C-MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 translocation testing

The following procedures may be helpful:

-

Nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy (essential)

-

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (essential)

-

Excisional lymph-node biopsy (essential in HL and NHL)

-

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy (essential).

-

Lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

-

Diagnostic tonsillectomy (if lymphoma of the tonsils is suspected)

-

Pulmonary function tests in patients to receive ABVD or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin [doxorubicin], cyclophosphamide, Oncovin [vincristine], procarbazine, prednisone)

-

Determination of baseline ejection fraction for patients to receive doxorubicin-based chemotherapy

A lymphoma specialist should perform staging and treatment. The Ann Arbor staging system is used to stage lymphomas.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Initial therapy for HL typically includes the following:

-

Stage I or II favorable disease – Combined chemotherapy (ABVD) and radiation or combined chemotherapy alone

-

Stage I or II unfavorable disease – Chemotherapy with or without radiation

-

Stage III or IV disease – Combination chemotherapy (eg, ABVD - which is standard and has more tolerable side effects), more intensive/aggressive regimens (eg, Stanford V and BEACOPP), brentuximab vedotin, [2] and actinomycin D, bleomycin, and vincristine (ABV) components

-

Nodular lymphocyte–predominant HL – Radiation or rituximab alone is often used; advanced-stage disease is usually treated like HL in patients with an unfavorable prognosis

Therapy for relapsing or refractory HL typically involves the following:

-

Early stage disease and relapse after radiation therapy alone – ABVD

-

Relapse after combined-modality therapy or chemotherapy alone – The same or other combination chemotherapy (if remission duration > 12 months)

-

Salvage therapy – ABVD; etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (ESHP); ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE); dose-adjusted etoposide phosphate, prednisone, Oncovin (vincristine sulfate), cyclophosphamide, and hydroxydaunorubicin (DA-EPOCH); or brentuximab vedotin [2]

-

Failed induction or relapse within a year of initial chemotherapy – High-dose chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy) followed by autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation

Therapy for NHL may include the following:

-

Indolent B-cell lymphoma (eg, follicular and small lymphocytic lymphoma) – Watch-and-wait strategy initially; fludarabine; anti-CD20; cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin (vincristine sulfate), and prednisone (CHOP); rituximab; or rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP); on an investigational basis, radioimmunotherapy or stem-cell transplantation

-

Stage I or II diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) – Combined modalities, R-CHOP; use of rituximab, DA-EPOCH, or both may eliminate the need for irradiation

-

Stage III or IV DLBCL – Combination chemotherapy (eg, CHOP and, subsequently, R-CHOP)

-

Relapsing DLBCL – Salvage chemotherapy (eg, rituximab and ICE [R-ICE]; etoposide, solumedrol, high-dose cytarabine, and the platinum agent cisplatin [ESHAP]; or rituximab and DA-EPOCH [DA-EPOCH-R]); responsive disease is often treated with autologous stem-cell transplantation

-

Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma – Methotrexate, rituximab, irradiation

-

Other aggressive B-cell lymphomas – Burkitt lymphoma is treated with intensive systemic chemotherapy; mantle-cell lymphoma is treated with measures ranging from aggressive combination chemotherapy to allogeneic transplantation; bortezomib may prove effective

Therapy for T-cell lymphomas may include the following:

-

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type – Irradiation (for localized disease)

-

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) – Systemic chemotherapy

-

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma – Poor results with standard therapy

-

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma – Intrathecal chemotherapy

Surgery for treatment of lymphomas of the head and neck is only performed in selected cases.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Otolaryngologists are frequently involved in the diagnosis of lymphoma. A quarter of all extranodal lymphomas occur in the head and neck, and 8% of findings on supraclavicular fine-needle aspiration biopsy yield a diagnosis of lymphoma. In White populations, lymphoma is a more common cause of cervical lymphadenopathy than metastatic disease. Lymphoma is the second most common primary malignancy occurring in the head and neck and importantly, with the incidence of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma having risen steadily over recent decades.

The image below shows a lymphoma of the head and neck.

Pathophysiology

Although a variety of histologic classification schemes have been used for lymphoma in the past, the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification update is currently used and is as follows [3] :

-

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL)

Nodular lymphocyte predominant

Classic

Nodular sclerosis classic

Mixed cellularity classic

Lymphocyte-rich classic

Lymphocyte-depleted classic

-

Mature B-cell neoplasms

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and classic HL

High-grade B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified

High-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements

Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration

Burkitt lymphoma

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) DLBCL, not otherwise specified

Primary effusion lymphoma

Plasmablastic lymphoma

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive (ALK+) large B-cell lymphoma

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis

DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation

EBV mucocutaneous ulcer

EBV DLBCL, not otherwise specified

Primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type

Primary DLBCL of the CNS

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma

DLBCL, not otherwise specified (germinal center B-cell type and activated B-cell type)

Mantle cell lymphoma (in situ mantle cell neoplasia)

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma

Large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement

Pediatric-type follicular lymphoma

Follicular lymphoma (in situ follicular neoplasia and duodenal-type follicular lymphoma)

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma (pediatric nodal marginal zone lymphoma)

Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma)

Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition diseases

Extraosseous plasmacytoma

Solitary plasmacytoma of bone

Plasma cell myeloma

Splenic B-cell lymphoma/leukemia, unclassifiable (splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma and hairy cell leukemia-variant)

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) - Immunoglobulin M (IgM; μ heavy chain, γ heavy chain, and α heavy chain)

MGUS - IgA/IgG

B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis

Hairy cell leukemia

Splenic marginal-zone lymphoma

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia)

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma

-

Mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms

- Adult T-cell leukemia or lymphoma

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALK positive and negative)

Breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in situations in which CD30 is expressed and ALK expression is absent; can present as a peri-prosthetic fluid collection and/or mass and usually occurs 8-10 years after implantation; all patients with breast implant–associated seromas occurring more than 1 year after implantation should have cytologic analysis; incidence is very low, but this is possibly due to poor understanding of the disease and/or misdiagnosis [4]

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma

Primary cutaneous CD8-positive aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphomas

Primary cutaneous acral CD8-positive T-cell lymphoma

Primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder

Primary cutaneous CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (lymphomatoid papulosis, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma)

Sézary syndrome

Mycosis fungoides

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma

Extranodal NK-cell or T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma

Indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract

Follicular T-cell lymphoma

Nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma with T–follicular helper cell (Tfh) phenotype

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia

Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells

Aggressive NK-cell leukemia

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood

Hydroa vacciniforme–like lymphoproliferative disorder

-

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD)

Plasmacytic hyperplasia

Infectious mononucleosis

Florid follicular hyperplasia

Polymorphic

Monomorphic (B-cell and NK/T-cell types)

Classic HL

-

Histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms

Histiocytic sarcoma

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Langerhans cell sarcoma

Indeterminate dendritic cell tumor

Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma

Fibroblastic reticular cell tumor

Disseminated juvenile xanthogranuloma

Erdheim-Chester disease

HL is characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells, and the subtype diagnosis depends on the cytoarchitectural milieu in which the Reed-Sternberg cells or their variants are found. Nodular sclerosis, mixed cellularity, lymphocyte-rich and lymphocyte-depleted subtypes are collectively termed classic HL. Nodular sclerosis is the most common subtype, especially in patients younger than 40 years, followed by mixed cellularity. Lymphocyte-predominant HL, more common in young men than in others, behaves more like a low-grade B-cell lymphoma than other tumors. In general, patients who are elderly, those who live in low-income countries, and those infected with HIV are most likely to have widespread disease with systemic symptoms at diagnosis.

Approximately 85% of NHLs are B-cell lymphomas. The most common indolent NHL is follicular lymphoma, which is derived from germinal center B cells. Other indolent histologies are lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, which has characteristics of B cells differentiating toward plasma cells, and marginal-zone lymphoma derived from the memory B-cell compartment, which includes MALT lymphomas. DLBCL is the most common aggressive NHL. On the basis of messenger RNA microarrays, most cases have profiles that indicate an origin from a germinal center B cell or a postgerminal-center activated B cell. Mantle cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma are aggressive NHLs that have the characteristics of normal B cells residing in the mantle zone or in the germinal center of a lymphoid follicle, respectively.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, such as mycosis fungoides, can be indolent. However, many T-cell NHLs are aggressive malignancies.

Mortality/Morbidity

For HL, overall 5-year survival rates in the United States are 83% for Whites and 77% for African Americans. For NHL, the 5-year survival rate is 53% for White patients and 42% for African Americans.

A study by Han et al using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database found overall survival rates in the United States for nasopharyngeal lymphoma to be 70%, 57%, and 45% at 2, 5, and 10 years, respectively, and determined median overall survival to be 8.2 years. Multivariate analysis indicated that overall and disease-specific survival rates are worse in patients with advanced age or NK/T-cell NHL and are improved in association with radiation therapy. [5]

A study by Anderson et al found that in adolescents and young adults aged 15-39 years, noncancer-related deaths rates were higher in NHL, HL, and head and neck cancer than in the general US population, with the standardized mortality ratios for these rates being 6.33, 3.12, and 2.09, respectively. The ratio was high for certain other cancers as well. [6]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Lymphoma is the fifth most common cancer in the United States, with an estimated annual incidence of 74,490 cases. Approximately 88% of these cancers are NHLs. The incidence of NHL has doubled over the last 20 years because of the increase in AIDS-related lymphoma (ARL) [7] ; an increase in the detection of lymphoma; an increase in the elderly population; and for other, poorly understood reasons.

International

The different histologic subtypes of NHL have various distributions and geographic predilections. The frequency of NK/T-cell lymphoma is increased in China, in Taiwan, in Southeast Asia, and in parts of Africa where Burkitt lymphoma is endemic.

Race

HL and, to a lesser extent, NHL are more common in Whites than in African Americans or Hispanics. Other races such as Asian/Pacific Islanders and American Indians have the lowest incidence and mortality rates.

Sex

The incidence of both HL and NHL is higher in men than in women, especially among older patients.

Age

In the United States, HL has a bimodal age distribution, with a peak incidence in people aged 20-34 years and a second peak in Whites aged 75-79 years and in African Americans aged 55-64 years. In Japan, the early peak is absent, and in some low-income countries, the early peak is seen in childhood.

The mortality rate increases with age. For example, incidence and mortality rates for NHL increase with age. In addition, Burkitt lymphoma represents 40-50% of all pediatric lymphomas but is uncommon in adults without AIDS.

Lymphoblastic lymphoma most commonly affects men aged 20-40 years who have lymphadenopathy and/or a mediastinal mass.

-

CT scan of a patient with a natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma of the right nasal cavity and maxillary sinus.

-

CT scan 6 months after treatment with 4 cycles of DA-EPOCH (ie, infused etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with bolus cyclophosphamide and prednisone).

-

CT scan of a patient with a recurrence of stage I-AE angiocentric lymphoma of the left maxillary sinus, treated 7 years earlier with 4 cycles of ProMACE-MOPP (ie, prednisone, methotrexate, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide–mechlorethamine [nitrogen mustard], vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) and 3960 cGy of radiation.

-

CT scan 2 years after salvage therapy.

-

Fiberoptic nasal examination of a patient with natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma of the right nasal cavity and maxillary sinus.