Overview

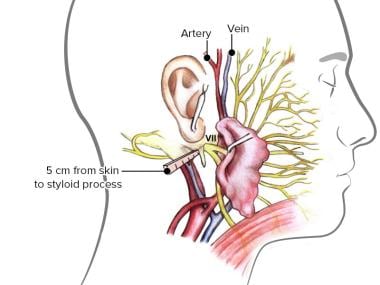

The facial nerve, or cranial nerve (CN) VII, is the nerve responsible for facial expression. The pathways of the facial nerve are variable, and knowledge of the key intratemporal and extratemporal landmarks is essential for accurate physical diagnosis and safe and effective surgical intervention in the head and neck (see the image below).

The facial nerve is composed of approximately 10,000 neurons, 7,000 of which are myelinated and innervate the nerves of facial expression. Three thousand of the nerve fibers are somatosensory and secretomotor and make up the nervus intermedius. The course of the facial nerve and its central connections can be roughly divided into the segments listed in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Segmental Description of the Facial Nerve and Central Connections (Open Table in a new window)

Segment |

Location |

Length, mm |

Supranuclear |

Cerebral cortex |

NA |

Brainstem |

Motor nucleus of facial nerve, superior salivatory nucleus of tractus solitarius |

NA |

Meatal segment |

Brainstem to internal acoustic meatus or canal (IAC) |

13-15 |

Labyrinthine segment |

Fundus of IAC to facial hiatus |

3-4 |

Tympanic segment |

Geniculate ganglion to pyramidal eminence |

8-11 |

Mastoid segment |

Pyramidal eminence to stylomastoid foramen |

10-14 |

Extratemporal segment |

Stylomastoid foramen to pes anserinus |

15-20 |

Facial nerve is a mixed nerve, composed of a motor root and a smaller sensory root, known as the nervus intermedius, which converge in the temporal bone. Its path includes intracranial, meatal (canalicular), labyrinthine, tympanic, mastoid, and extratemporal segments, each with distinct anatomical boundaries and clinical significance. [1, 2]

The objective of this article is to briefly review the anatomy of the facial nerve in each of these segments and to follow the nerve from its most proximal origin to its end organ, i.e., the muscles of facial expression.

Embryology of the Facial Nerve

By the third week of gestation, the facioacoustic primordium gives rise to CN VII and VIII. During the fourth week, the chorda tympani can be discerned from the main branch. The former courses ventrally into the first branchial arch and terminates near a branch of the trigeminal nerve that eventually becomes the lingual nerve. The main trunk courses into the mesenchyme, approaching the epibranchial placode.

The geniculate ganglion, nervus intermedius, and greater petrosal nerve are visible by the fifth week.

The second branchial arch gives rise to the muscles of facial expression in the seventh and eighth week. To innervate these muscles, the facial nerve courses across the region that eventually becomes the middle ear. By the eleventh week, the facial nerve has arborized extensively. In newborns, the facial nerve anatomy approximates that of an adult, except for its location in the mastoid, which is more superficial.

Research on human embryos at stages 13-15 has provided detailed insights into the early formation of the facial nerve and its relationship with the vestibulocochlear ganglion. [3]

Neuroanatomical studies have explored connections between the facial and trigeminal nerves, emphasizing their functional significance in proprioception and sensorimotor control. [4]

Central Connections

The facial nerve, or CN VII, has a complex anatomy with both central and peripheral connections, allowing it to serve multiple functions. It is primarily responsible for motor innervation to the muscles of facial expression, but it also has sensory and parasympathetic components that contribute to taste and glandular control. [1]

Crosby and DeJonge, along with Nelson, have provided two of the most complete descriptions of the central connections of the facial nerve. [5, 6] The reader is referred to these references for a more detailed description of the supranuclear and nuclear organization of the facial nerve.

The facial nerve (CN VII) is primarily involved in the motor control of facial expressions and has distinct pathways for upper and lower facial muscles. Literature emphasizes that upper motor neuron (UMN) pathways innervate the upper face bilaterally, while the lower face receives contralateral innervation. This differential innervation explains clinical presentations seen in conditions such as facial nerve palsy, where UMN lesions typically spare the forehead muscles due to a bilateral cortical input, whereas lower motor neuron (LMN) lesions result in paralysis of both the upper and lower facial muscles on the affected side. [1, 7]

The facial nerve's central connections begin in the brainstem, specifically in the pons, where it divides into a motor root and a smaller sensory root, often referred to as the nervus intermedius. After traveling through the internal acoustic meatus and fusing within the facial canal, it forms the geniculate ganglion before branching off to innervate various facial muscles and glands. These intricate connections show the nerve's vulnerability to lesions and the wide-ranging symptoms that can manifest from facial nerve damage, including motor impairment, altered taste, and dry eyes or mouth syndromes. [1, 7, 8]

The facial nerve consists of three nuclei: the main motor nucleus, the parasympathetic nuclei, and the sensory nucleus. [1]

The facial nerve nuclei receive significant afferent input from other brainstem nuclei. Notably, input from the trigeminal nerve supports reflex actions such as the corneal reflex, while acoustic nuclei contribute to reflexive responses to auditory stimuli. This integration shows the facial nerve's role not only in voluntary movement but also in reflexive actions critical for protecting sensory organs. [1, 8]

Cortex and internal capsule

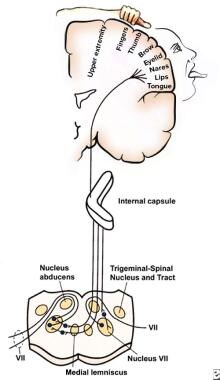

The voluntary responses of the facial muscles (e.g., smiling when taking a photograph) arise from efferent discharge from the motor face area of the cerebral cortex. The motor face area is situated on the precentral and postcentral gyri. The facial motor nerves are represented on the homunculus diagram below with the forehead located to the uppermost side and the eyelids, midface, nose, and lips sequentially located more inferiorly (see also Table 2 below).

This homunculus illustrates the location on the motor strip of facial areas relative to the hand and upper extremities. The lower half of the figure depicts the anatomy of the pyramidal system.

This homunculus illustrates the location on the motor strip of facial areas relative to the hand and upper extremities. The lower half of the figure depicts the anatomy of the pyramidal system.

Discharge from the facial motor area is carried through fascicles of the corticobulbar tract to the internal capsule, then through the upper midbrain to the lower brainstem, where they synapse in the pontine facial nerve nucleus. The pontine facial nerve nucleus is divided into an upper and lower half bilaterally.

The corticobulbar tracts from the upper face cross and recross en route to the pons; the tracts to the lower face cross only once.

In 1987, Jenny and Saper performed an extensive study of the proximal facial nerve organizations in a primate model and found evidence that in monkeys, upper facial movement is relatively preserved in UMN injuries because these motor neurons receive relatively little direct cortical input. In contrast, the lower facial muscles are more severely affected because their motor neurons depend on significant cortical innervation. The authors believe these observations also explain similar findings in humans. [9]

In their study, Jenny and Saper found that the descending corticofacial fibers in monkeys innervated the lower facial motor nuclear region bilaterally but with contralateral predominance. The upper facial motor nuclear regions received scant direct cortical innervation on either side of the brain.

The deficits observed with unilateral ablation of the corticobulbar fibers reflect the fact that upper facial motor neurons do not receive significant cortical innervations and that lower facial motor neurons that are contralateral to the lesion, which have functional loss, are dependent on direct contralateral cortical innervation, with the remaining ipsilateral cortical projections being insufficient to drive them. These findings may explain why a focal lesion in the facial area on one side of the motor cortex in humans spares eyelid closure and forehead movement but results in paralysis of the lower face.

Table 2. Summary of Innervation and Actions of Facial Mimetic Muscles (Open Table in a new window)

Branch of CN VII |

Location of Lesion |

Actions |

Posterior auricular |

Posterior auricular |

Pulls ear backward |

Occipitofrontalis, occipital belly |

Moves scalp backward |

|

Temporal |

Anterior auricular |

Pulls ear forward |

Superior auricular |

Raises ear |

|

Occipitofrontalis, frontal belly |

Moves scalp forward |

|

Corrugator supercilii |

Pulls eyebrow medially and downward |

|

Procerus |

Pulls medial eyebrow downward |

|

Temporal and zygomatic |

Orbicularis oculi |

Closes eyelids and contracts skin around eye |

Zygomatic and buccal |

Zygomaticus major |

Elevates corners of mouth |

Buccal |

Zygomaticus minor |

Elevates upper lip |

Levator labii superioris |

Elevates upper lip and midportion nasolabial fold |

|

Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi |

Elevates medial nasolabial fold and nasal ala |

|

Risorius |

Aids smile with lateral pull |

|

Buccinator |

Pulls corner of mouth backward and compresses cheek |

|

Levator anguli oris |

Pulls angles of mouth upward and toward midline |

|

Orbicularis |

Closes and compresses lips |

|

Nasalis, dilator naris |

Flares nostrils |

|

Nasalis, compressor naris |

Compresses nostrils |

|

Buccal and marginal mandibular |

Depressor anguli oris |

Pulls corner of mouth downward |

Depressor labii inferioris |

Pulls lower lip downward |

|

Marginal mandibular |

Mentalis |

Pulls skin of chin upward |

Cervical |

Platysma |

Pulls down corners of mouth |

Caution is advised in using the preservation of forehead function to diagnose a central lesion. Patients may have sparing of forehead function with lesions in the pontine facial nerve nucleus, with selective lesions in the temporal bone, or with an injury to the nerve in its distribution in the face. An accurate neurologic diagnosis is best made by examining deficits in conjunction with "the company they keep." A cortical lesion that produces a lower facial deficit is usually associated with a motor deficit of the tongue and weakness of the thumb, fingers, or hand on the ipsilateral side.

Nerve fibers influencing facial expressions are thought to arise in the thalamus and globus pallidus. Supranuclear pyramidal lesions spare movements of the face initiated as emotional responses and reflexes. With nuclear and infranuclear lesions, involuntary and voluntary facial movement is lost.

The facial nerve nuclei also receive afferent input from other brainstem nuclei. Input from the trigeminal nerve and nucleus form the basis of the trigeminofacial reflexes, e.g., the corneal reflex. Input from the acoustic nuclei to the facial nerve nucleus forms part of the stapedial reflex response to loud noises.

Extrapyramidal system

The extrapyramidal system consists of the basal nuclei and the descending motor projections other than the fibers of the pyramidal or corticospinal tracts. This system is associated with spontaneous, emotional, mimetic facial motions. The interplay between the pyramidal and extrapyramidal systems accounts for the resting tone and stabilizes the motor responses. The masked facies associated with Parkinsonism are known to be the result of destruction of the extrapyramidal pathways, leading to reduced spontaneous facial expressions, known as hypomimia. This condition can create a disconnect in social interactions as patients may appear disinterested or emotionally flat despite their internal feelings. [10]

Advances in technology have led to the development of automated systems for detecting hypomimia in patients with Parkinson's disease. These systems analyze facial expressions through machine learning algorithms to differentiate between healthy individuals and those with Parkinson's disease. [10]

Facial dystonia seen in Meige syndrome is thought to be due to basal nuclei disease. This syndrome leads to dystonic movements affecting the face and neck, often manifesting as blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia. [11]

Lower midbrain

A lesion in the lower midbrain above the level of the facial nucleus may cause: [1]

Contralateral paresis of the face and muscles of the extremities: This occurs due to disruption of the corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts. This type of supranuclear or central facial nerve palsy spares the forehead due to bilateral innervation of the upper facial muscles.

Ipsilateral abducens muscle paresis: This is a result of damage to the abducens nerve (CN VI), leading to impaired lateral eye movement or lateral gaze palsy.

Ipsilateral internal strabismus: This condition arises due to weakness in the lateral rectus muscle, which is innervated by the abducens nerve.

Ipsilateral facial paralysis: If the lesion extends far enough laterally to include the emerging facial nerve fibers, a peripheral type of ipsilateral facial paralysis may be apparent. This phenomenon is characterized by weakness in the facial muscles on the same side as the lesion, which is consistent with peripheral facial nerve injury.

Pons

The facial motor nucleus is located in the lower third of the pons, beneath the fourth ventricle. The neurons leaving the nucleus pass around the abducens nucleus as they emerge from the brainstem. Involvement of the facial nerve nucleus and sixth nerve nucleus are suggestive of a lesion near the fourth ventricle. A lesion near the ventricle at the level of the superior salivatory nucleus may result in dry eyes in addition to peripheral facial paralysis and abducens paresis. Many syndromes are known to result from pontine lesions, some of which are summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Syndromes Associated with Central Lesions (Open Table in a new window)

Syndrome |

Location of Lesion |

Characteristic Feature |

Foville syndrome |

Lateral pons |

Ipsilateral facial paresis, ipsilateral facial analgesia, ipsilateral Homer syndrome, ipsilateral deafness |

Meige syndrome |

Basal nuclei |

Facial dystonia |

Millard-Gubler syndrome |

Pontine nucleus |

Unilateral sixth nerve palsy, ipsilateral seventh nerve palsy, contralateral hemiparesis [12] |

Möbius syndrome |

Fundus of IAC to facial hiatus |

Ipsilateral facial paresis, ipsilateral abducens (CN VI) palsy |

Parkinson disease |

Extrapyramidal pathways |

Masked facies |

Pseudobulbar palsy |

Pontine |

Bilateral facial paresis with other CN defects, hyperactive gag reflex, hyperreflexia associated with hypertension, emotional lability |

Weber syndrome |

Upper midbrain |

Ipsilateral loss of direct and consensual pupillary light reflexes, ipsilateral external strabismus, oculomotor paresis |

Cerebellopontine Angle and the Internal Acoustic Meatus

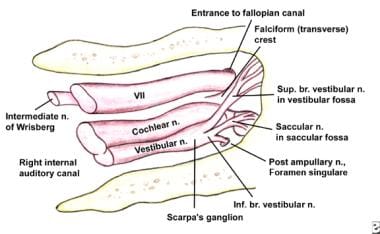

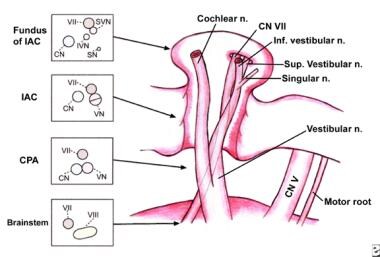

The facial nerve emerges from the brainstem with the nerve of Wrisberg, i.e., the nervus intermedius (see the image below). The nervus intermedius gained its name from its position as it courses across the cerebellopontine angle (CPA) between the facial nerve and the vestibulocochlear nerves (i.e., CN VII and CN VIII). The average distance between the point where the nerves exit the brainstem and the place where they enter into the internal acoustic meatus (internal auditory canal [IAC]) is approximately 15.8 mm. However, imaging studies indicate that this distance can vary, with some reports suggesting a length of about 24 mm for the cisternal segment of the facial nerve, which extends from its origin to the IAC. [13] The facial nerve and the nervus intermedius lie above and slightly anterior to CN VIII.

This drawing shows the contents of the right internal acoustic meatus. Note the relationship between the nervus intermedius (ie, nerve of Wrisberg) and the facial nerve. Also note the superior location of the facial nerve relative to the vestibulocochlear nerve.

This drawing shows the contents of the right internal acoustic meatus. Note the relationship between the nervus intermedius (ie, nerve of Wrisberg) and the facial nerve. Also note the superior location of the facial nerve relative to the vestibulocochlear nerve.

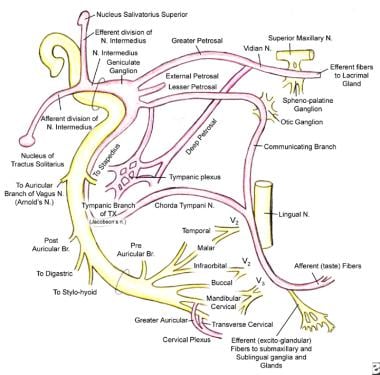

The nervus intermedius conveys (1) afferent taste fibers from the chorda tympani nerve, which come from the anterior two thirds of the tongue; (2) taste fibers from the soft palate via the palatine and greater petrosal nerves; and (3) preganglionic parasympathetic innervation to the submandibular, sublingual, and lacrimal glands.

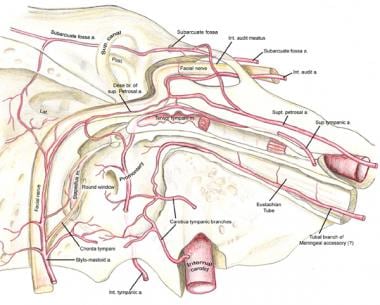

The fibers for taste originate in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS), and the fibers to the lacrimal, nasal, palatal mucus and submandibular glands originate in the superior salivatory nucleus. Fibers to the lacrimal gland are carried with the greater petrosal nerve until it exits the skull, at which point the fibers join the deep petrosal nerve (sympathetic fibers) to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (Vidian nerve), as shown in the image below.

Schematic illustration shows the facial nerve and its peripheral connections. Note the interconnections of cranial nerve (CN) VII with CN V, CN IX, and CN X.

Schematic illustration shows the facial nerve and its peripheral connections. Note the interconnections of cranial nerve (CN) VII with CN V, CN IX, and CN X.

Epidemiologic studies have highlighted an increasing incidence of tumors involving the IAC, with symptoms often including vertigo and sensorineural hearing loss. The relationship between tumor size, location within the IAC, and resulting auditory dysfunction has been emphasized; larger tumors tend to correlate with more significant hearing impairment due to increased pressure within the confines of the IAC. [14, 15]

Nervus intermedius and vestibulocochlear nerve

The nervus intermedius is a critical component of the facial nerve (CN VII), comprising sensory and parasympathetic fibers. It plays a significant role in innervating the lacrimal gland as well as the nasopalatine glands. It contributes to taste sensation in the anterior two thirds of the tongue and provides general sensation to areas around the auricle and external auditory canal. [1]

The nervus intermedius also has a small cutaneous sensory component from afferent fibers originating from a small portion of the auricle and postauricular area.

The close anatomic association between the facial nerve, the nervus intermedius, and the vestibulocochlear nerve at the level of the CPA and in the IAC may result in disturbances in tearing, taste, salivary gland flow, hearing, balance, and facial function as a result of lesions at this level. Common examples are the symptoms of tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and balance disturbances often associated with acoustic schwannomas. Large acoustic schwannomas may progress to involve the facial nerve and even CN V, CN IX, CN X, and CN XI.

The facial nerve and the nervus intermedius enter the IAC with the vestibulocochlear nerve. The gross and microscopic anatomic relationships among the locations of CN VII, CN VIII, and the nervus intermedius are of surgical importance. The vestibulocochlear nerve enters the IAC inferiorly (caudad). The facial nerve runs superiorly (cephalad) along the roof of the IAC. A useful mnemonic for remembering this relationship is "Seven-up over Coke" (see the image below).

Spatial anatomic relationship between the nerves traveling through the internal acoustic meatus is shown. Note the changing spatial relationship between the facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII) and the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). IAC = internal auditory canal (acoustic meatus); CPA = cerebellopontine angle

Spatial anatomic relationship between the nerves traveling through the internal acoustic meatus is shown. Note the changing spatial relationship between the facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII) and the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). IAC = internal auditory canal (acoustic meatus); CPA = cerebellopontine angle

At the fundus of the IAC, the falciform crest (crista falciformis) divides the IAC into superior and inferior compartments. The facial nerve passes along the superior part of the ledge, separated from the superior vestibular nerve by a vertical bony ridge named the Bill bar (after the esteemed Dr William House).

Literature emphasizes that injuries to the nervus intermedius during surgeries for vestibular schwannomas are not sufficiently acknowledged. Preservation of its function is vital for maintaining the overall facial nerve integrity as damage can lead to significant postoperative complications such as dry eyes due to lacrimal gland dysfunction and altered taste perception. [16]

Intratemporal Course of the Facial Nerve

The facial nerve travels through the petrous temporal bone, as shown in the image below, in a bony canal called the facial or fallopian canal (after Gabriel Fallopius). No other nerve in the body travels such a long distance through a bony canal. Because of this bony shell around the nerve, inflammatory processes involving the central nervous system and the facial nerve or traumatic injuries to the temporal bone can cause unique complications.

The intratemporal segment of the facial nerve is particularly susceptible to damage from both traumatic injuries and pathologic conditions such as Bell's palsy. The timeline for Wallerian degeneration, a process that occurs after nerve injury, indicates that significant changes in nerve function can take 72 hours to manifest in distal segments, which complicates early diagnosis and intervention strategies. [17]

Anatomical studies have shown that branches of the facial nerve may exhibit variations in their course, which can impact surgical approaches and increase the risk for inadvertent injury during interventions in this region. [17, 18]

The transtemporal course of the facial nerve is shown. Note the vascular arcades feeding the facial nerve throughout its course in the bony facial canal.

The transtemporal course of the facial nerve is shown. Note the vascular arcades feeding the facial nerve throughout its course in the bony facial canal.

Labyrinthine (proximal) segment

The labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve lies beneath the middle cranial fossa and is the shortest segment in the facial canal (approximately 3.5-4 mm in length). In this segment, the nerve is directed obliquely forward, perpendicular to the axis of the temporal bone, as shown above. The facial nerve and the nervus intermedius remain distinct entities at this level. The term labyrinthine segment is derived from the location of this segment of the nerve immediately posterior to the cochlea. The nerve is posterolateral to the ampullated ends of the horizontal and superior semicircular canals and rests on the anterior part of the vestibule in this segment.

The labyrinthine segment is the narrowest part of the facial nerve and is susceptible to compression by means of edema. This is the only segment of the facial nerve that lacks anastomosing arterial cascades, making the area vulnerable to embolic phenomena, low-flow states, and vascular compression. The arterial supply to this segment primarily comes from the labyrinthine artery, a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), which supplies blood to both the meatal and labyrinthine segments. [19]

After traversing the labyrinthine segment, the facial nerve changes direction to form the first genu (i.e., bend or knee), marking the location of the geniculate ganglion. The geniculate ganglion is formed by the juncture of the nervus intermedius and the facial nerve into a common trunk. The geniculate ganglion is the sensory ganglion of the facial nerve, supplying taste fibers from the anterior two thirds of the tongue via chorda tympani, as well as taste fibers from the palate via the greater petrosal nerve.

The greater petrosal nerve branches from the geniculate ganglion, and there may be an additional branch, the external petrosal nerve.

Petrosal nerves

The greater petrosal nerve emerges from the upper portion of the ganglion and carries secretomotor fibers to the lacrimal gland. The greater petrosal nerve exits the petrous temporal bone via the hiatus for the greater petrosal nerve to enter the middle cranial fossa. The nerve passes deep to the trigeminal (Gasserian) ganglion and across the foramen lacerum to enter the pterygoid canal.

In the pterygoid canal, the greater petrosal nerve joins the deep petrosal nerve to become the nerve of the pterygoid canal. The parasympathetic axons in this nerve synapse in the pterygopalatine ganglion; postganglionic parasympathetic fibers, which are carried via branches of the maxillary (V2) divisions of the trigeminal nerve (CN V), innervate the lacrimal gland and mucus glands of the nasal and oral cavities.

Studies have shown the clinical importance of the greater petrosal nerve. Lesions affecting this nerve can lead to conditions such as xerophthalmia (dry eyes), facial palsy, and altered taste sensations. Understanding its anatomy is vital for surgical procedures involving the middle cranial fossa as it serves as a landmark for identifying critical structures during operations, thereby reducing risks for injury to surrounding nerves and arteries. Literature has also documented rare conditions such as schwannomas associated with the greater petrosal nerve. These tumors can present with symptoms such as facial nerve palsy and hearing loss, emphasizing the need for careful imaging and surgical planning when addressing such cases. [20, 21, 22]

The external petrosal nerve is an inconstant branch that carries sympathetic fibers to the middle meningeal artery; however, it is not as well known. [23] Imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans have allowed for more precise identification of these nerves and their pathways, assisting in both clinical and surgical approaches to facial nerve-related conditions and treatments for related dysfunctions, including lacrimation disorders and nerve compression syndromes. [24]

Tympanic (horizontal) segment

The tympanic segment extends from the geniculate ganglion to the horizontal semicircular canal and is 8-11 mm in length. The nerve passes behind the cochleariform process and the tensor tympani. The cochleariform process is a useful landmark for finding the facial nerve. The nerve lies against the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, above and posterior to the oval window. The wall can be very thin or dehiscent in this area, and the middle ear mucosa may lay in direct contact with the facial nerve sheath.

The facial canal has been reported to be dehiscent in the area of the oval window in 25-55% of the postmortem specimens. Always anticipate finding a dehiscent or prolapsed facial nerve in its tympanic segment, especially in patients with congenital ear deformities.

The distal portion of the facial nerve emerges from the middle ear between the posterior wall of the external auditory canal and the horizontal semicircular canal. This is just distal to the pyramidal eminence, where the facial nerve makes a second turn (marking the second genu).

The most important landmarks for identifying the facial nerve in the mastoid are the horizontal semicircular canal, the fossa incudis, and the digastric ridge. The second genu of the facial nerve runs inferolateral to the lateral semicircular canal. This is a relatively constant relationship.

In cases in which the lateral canal is difficult to identify (e.g., cholesteatoma, tumor), the use of other landmarks along with cautious exploration is advised.

The digastric ridge points to the lateral and inferior aspect of the vertical course of the facial nerve in the temporal bone. In poorly pneumatized temporal bones, the digastric ridge may be difficult to identify.

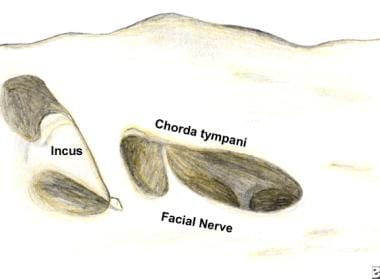

The distal aspect of the tympanic segment can be surgically located via a facial recess approach. The chorda tympani nerve and the fossa incudis can be used to identify the nerve when a facial recess approach is employed, shown in the image below.

Exposure of the facial nerve after a cortical mastoidectomy. The facial recess has been opened by thinning of the posterior canal wall. The recess is identified using the incus, chorda tympani, and horizontal semicircular canal as landmarks.

Exposure of the facial nerve after a cortical mastoidectomy. The facial recess has been opened by thinning of the posterior canal wall. The recess is identified using the incus, chorda tympani, and horizontal semicircular canal as landmarks.

The long process of the incus points toward the facial recess. The chorda tympani nerve serves at the lateral margin of the triangular facial recess. The chorda tympani nerve can be exposed along its length and can be followed inferiorly and medially to its takeoff from the main trunk of the facial nerve. In practice, surgeons most likely employ cues from all these landmarks in respecting the integrity of the facial nerve.

Injuries to the tympanic segment are prevalent during middle ear surgeries. A study found that 62.5% of iatrogenic facial nerve injuries occurred at this site, with many patients experiencing varying degrees of nerve damage. Surgical management strategies included decompression, grafting, and anastomosis depending on the severity of the injury. [25]

Mastoid segment

The second genu marks the beginning of the mastoid segment. The second genu is lateral and posterior to the pyramidal process. The nerve continues vertically down the anterior wall of the mastoid process to the stylomastoid foramen. The mastoid segment is the longest part of the intratemporal course of the facial nerve, approximately 10-14 mm long. During middle ear surgery, the facial nerve is most commonly injured at the pyramidal turn.

Reports indicate that iatrogenic injuries to the facial nerve during primary mastoidectomy occur at the rates of 0.6-3.7%, with higher rates (4.0-10%) observed during revision surgeries. [26]

The three branches that exit from the mastoid segment of the facial nerve are:

(1) The nerve to the stapedius muscle: This branch originates behind the pyramidal eminence of the posterior wall of the tympanic cavity. It passes forward through a small canal to reach the stapedius muscle. [1, 26]

(2) The chorda tympani nerve: It arises from the facial nerve about 6 mm above the stylomastoid foramen. It runs anterosuperiorly in a canal to enter the tympanic cavity via the posterior canaliculus. [1] The chorda tympani is the terminal branch of the nervus intermedius. The chorda runs laterally in the middle ear, between the incus and the handle of the malleus, and forward across the inner aspect of the upper portion of the tympanic membrane. After passing through the tympanic cavity in this way, the nerve exits the base of the skull through the petrotympanic fissure (i.e., canal of Huguier) to join the lingual nerve. The chorda tympani nerve carries preganglionic parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to the submandibular and sublingual glands. This nerve also carries special sensory afferent fibers (i.e., taste fibers) from the anterior two thirds of the tongue and fibers from the posterior wall of the external acoustic meatus responsible for pain, temperature, and touch sensations.

(3) The nerve from the auricular branch of the vagus: The auricular branch of the vagus nerve arises from the jugular foramen and joins the facial nerve just distal to the point at which the nerve to the stapedius muscle arises. Pain fibers from the external acoustic meatus may be carried with this nerve.

Studies have highlighted variability in anatomical features such as exit angles of the mastoid segment; most commonly, an obtuse exit angle was observed in approximately 90.7% of cases. The length of this segment can also vary, with some studies reporting lengths up to 15 mm, showing individual anatomical differences that may influence surgical approaches and risk assessments during procedures involving this area. [26]

Understanding these anatomical details is crucial for clinicians performing surgeries in proximity to the facial nerve. The mastoid segment's unique morphology can influence surgical strategies, particularly in cases involving facial nerve neuromas or other pathologies affecting this region. For instance, facial nerve neuromas in this segment are rare but present significant challenges due to their complex relationships with the surrounding structures and high risks associated with surgical intervention. [27]

Extratemporal Facial Nerve

The facial nerve exits the facial canal via the stylomastoid foramen. The nerve travels between the digastric and stylohyoid muscles and enters the parotid gland.

Several useful landmarks are used to locate the facial nerve. Topographic landmarks, shown in the image below, can serve as guides for locating the course of the facial nerve and its branches. For example, a line drawn between the mastoid tip and the angle of the mandible can serve as a useful landmark for the superior limits of a neck dissection. Removal of the parotid tissue inferior to this line can be performed relatively safely.

The topographic trajectory of the temporal and/or marginal mandibular branches (MMBs) should be identified during a rhytidoplasty, submandibular gland excision, and/or neck dissection. The temporal branch can be roughly located along a line extending from the attachment of the lobule (approximately 5 mm below the tragus), anterior and superior to a point 1.5 cm above the lateral aspect of the ipsilateral eyebrow. [28, 29]

Surgical landmarks to the facial nerve include the tympanomastoid suture line, the tragal pointer, and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The tympanomastoid suture line lies between the mastoid and tympanic segments of the temporal bone and is approximately 6-8 mm lateral to the stylomastoid foramen. The main trunk of the nerve can also be found midway between (10 mm posteroinferior to) the bluntly pointed medial edge of the tragal cartilage, the so-called "tragal pointer," and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The nerve is usually located inferior and medial to the pointer.

During surgical dissection, the surgeon may encounter a branch from the occipital artery that lies lateral to the facial nerve. Brisk bleeding at this time may be a sign that the nerve is in close proximity; hemostasis should be obtained using bipolar electrocautery, and further dissection should proceed cautiously. The styloid process is deep to the main trunk of the nerve.

In the infant and young child, these landmarks are not applicable because of differences in the rate of anatomic development of the parotid gland and mastoid. The modified Blair incision most commonly used in adults is often avoided in children because the facial nerve is located more superficially, and the risk for injury is increased with elevation of the skin flaps. Many textbooks on pediatric otolaryngology provide detailed descriptions of the safe placement of surgical incisions for exposing the facial nerve and its branches in children.

Once it has exited the facial canal at the stylomastoid foramen, the facial nerve gives off several rami before dividing into its main branches. A sensory branch exits the nerve immediately below the stylomastoid foramen and innervates the posterior wall of the external acoustic meatus and a portion of the tympanic membrane. Next, the posterior auricular nerve leaves the facial nerve and innervates the posterior auricular and occipitalis muscles. Two small branches innervate the stylohyoid muscle and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

The facial nerve crosses lateral to the styloid process and enters the parotid gland. The nerve lies in a fibrous plane that separates the deep and superficial lobes of the parotid gland. In the parotid gland, the nerve divides into two major divisions at the so-called pes anserinus, i.e., the superiorly directed temporofacial and the inferiorly directed cervicofacial divisions of the facial nerve.

After the main point of division, five major branches of the facial nerve exist as follows:

-

Temporal (i.e., frontal)

-

Zygomatic

-

Buccal

-

Marginal mandibular

-

Cervical

The facial nerve innervates all the muscles of facial expression. Of these, the facial nerve innervates 14 of the 17 paired muscle groups of the face on their deep side. The three muscles innervated on their superficial or lateral edges are the buccinator, levator anguli oris, and mentalis muscles. Frequent connections between the buccal and zygomatic branches exist. The temporal and MMBs are at the highest risk during surgical procedures and are usually terminal connections without anastomotic connections.

Studies emphasize the variability in the branching patterns of the facial nerve. While the classic bifurcation into temporofacial and cervicofacial branches remains the most common pattern, several studies highlight interconnections between branches, which occur in approximately 23% of the cases. Additionally, variations in the branching patterns have clinical implications, particularly in surgeries involving the parotid gland or neck, where facial nerve injury risks are higher due to anatomical diversity. [30]

Branch-specific injuries show predictable effects; for example, trauma to the zygomatic or buccal branches can affect expression near the eyes and mouth. This pattern highlights the importance of having a thorough knowledge of facial nerve anatomy when assessing trauma-related facial paralysis. [31]

Superficial musculoaponeurotic system

The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) is often described as a fibrous network composed of collagen and elastic fibers that interconnects the facial muscles. [32] It is a superficial fascial layer that extends throughout the cervicofacial region. In the lower face, SMAS invests the facial muscles and is continuous with the platysma muscle. Superiorly, SMAS ends at the level of the zygoma because of attachments of the fascial layers to the ZA.

Literature suggests that SMAS may not exist as a distinct anatomical layer in all the areas of the face. Instead, it may represent a combination of structures that include the platysma and various fascial layers. Some studies indicate that SMAS is primarily present where flat mimetic muscles are located, such as over the posterior part of the parotid gland, but may not be consistently identifiable in other regions. [33]

The temporoparietal fascia is not continuous with SMAS, but they are most likely embryologic equivalents. The temporoparietal fascia extends from the ZA as an extension of the deep temporal fascia. In the temporal region, the temporal branch of the facial nerve crosses the ZA and courses within the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia (temporoparietal fascia).

In the scalp, the equivalent of SMAS is the galea aponeurotica, which provides he aponeurotic attachment for the frontalis, occipitalis, procerus, and some of the auricular muscles. In the upper face, the neurovascular structures exit their bony foramina and penetrate the SMAS to run within its superficial aspects or on its surface.

SMAS encloses all the facial muscles and is their only attachment to the overlying dermis, thus transmitting contractions of the facial muscles to the overlying skin. A conceptual understanding of the anatomy of SMAS is important to the surgeon. In the lower face, the facial nerve always runs deep to the platysma and SMAS and innervates the muscles on their undersurfaces (except for the buccinator, levator anguli oris, and mentalis muscles). SMAS also helps surgeons to identify the location of the facial nerve during dissection toward the midline of the face, where the nerve can be found running on top of the masseter muscle just below the SMAS.

Understanding the anatomical relationship between SMAS and facial nerve branches is essential for surgical procedures such as rhytidectomy (facelift surgery). The risk for nerve injury is particularly high when dissection occurs in deeper planes beneath the SMAS, where branches of the facial nerve are located. [34]

The role of SMAS in facial aesthetics has been highlighted in recent studies focusing on rejuvenation techniques. Procedures that involve SMAS manipulation, such as SMAS-platysma facelifts, have been shown to provide more natural results compared with traditional techniques by effectively lifting and repositioning facial structures without excessive tension on the overlying skin. Additionally, ongoing research continues to explore age-related changes in the SMAS, revealing variations in its thickness and structural integrity that may influence surgical outcomes. [32]

Temporal branches

The relationships of the temporal branch are complex and only briefly described in this article. Refer to Larrabee and Makielski for a more complete anatomic description.7 The temporal branch of the facial nerve exits the parotid gland and runs within the SMAS over the ZA into the temple region. The temporal branch enters the undersurface of the frontalis muscle and lies superficial to the deep temporalis fascia. To avoid injury to the temporal branch during elevation of facial flaps, the surgeon should elevate either in a subcutaneous plane or deep to the SMAS.

The temporal branch also innervates several key muscles, including the frontalis and orbicularis oculi, which are crucial for facial expressions above the palpebral fissure. [35]

Anatomical studies have provided detailed insights into the temporal branch's course and its relationship with surrounding structures. A clinical study in which fresh adult cadaver specimens were dissected documented that the temporal branch crosses the ZA at varying depths, classified into three types based on its trajectory. In the ZA area, the occurrence of a single running TB (type I), two branches (type II), and three branches (type III). [35] The mean distance from the tragus to where the TB enters the orbicularis oculi muscle has been measured at approximately 74.72 mm, highlighting its proximity to critical facial landmarks. [36]

Understanding the precise anatomy of the TB is essential for surgeons to minimize risks during operations. TB can be damaged during various surgical procedures, including frontotemporal craniotomies and cosmetic surgeries. Studies indicate that maintaining a subcutaneous or deep SMAS plane during flap elevation can help preserve this nerve branch. [36]

Moreover, anatomical studies report that the TB can split into multiple rami (ranging from 2-5 branches), which can complicate surgical approaches if not properly identified. [35, 36]

Marginal mandibular branches

The MMB lies along the body of the mandible (80%) or within 1-2 cm below (20%). This is a critical landmark in head and neck surgery. The MMB lies deep to the platysma throughout much of its course. It becomes more superficial approximately 2 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth and ends on the undersurface of the muscles. Injury to the MMB results in paralysis of the muscles that depress the corner of the mouth. Surgical procedures such as rhytidoplasty, parotidectomy, and submandibular gland excision pose risks to this nerve due to its variable anatomy. [37]

Cadaveric studies have highlighted significant variability in the branching patterns of the MMB. For instance, one study found that in 42% of the cases, there was a single branch, while 14% exhibited two rami and 2% had three rami. Notably, 20.3% of MMBs were found above the inferior border of the mandible, while 45.8% were along the mandible, and 33.9% were below it. [38]

Findings suggest that exposure of the MMB at specific anatomical landmarks can significantly reduce injury rates during surgery. Dissection at the mandibular angle where the platysma muscle flaps are utilized has shown a lower incidence of nerve damage (approximately 2.94%) than other methods. [39]

Surgeons are advised to beware of the anatomical variations in MMB when planning incisions or dissections in the submandibular region. Studies recommend positioning surgical maneuvers at least 4.5 cm anterior to the gonion (the angle of the mandible) and keeping incisions more than 2 cm below the mandible to minimize risk. [37]

Facial Nerve Paralysis

The spectrum of facial motor dysfunction is wide, and characterizing the degree of paralysis can be difficult. Several systems have been proposed, but since the mid-1980s, the House-Brackmann system has been widely used. In this scale, grade I is assigned to normal function, and grade VI represents complete paralysis. Intermediate grades vary according to function at rest and with effort. The House-Brackmann designations are summarized in Table 4 below.

Table 4. House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Grading System (Open Table in a new window)

Grade |

Description |

Characteristics |

I |

Normal |

Normal facial function in all areas |

II |

Mild dysfunction |

Slight weakness noticeable on close inspection; may have very slight synkinesis |

III |

Moderate dysfunction |

Obvious, but not disfiguring, difference between 2 sides; noticeable, but not severe, synkinesis, contracture, or hemifacial spasm; complete eye closure with effort |

IV |

Moderately severe dysfunction |

Obvious weakness or disfiguring asymmetry; normal symmetry and tone at rest; incomplete eye closure |

V |

Severe dysfunction |

Only barely perceptible motion; asymmetry at rest |

VI |

Total paralysis |

No movement |

Several updated grading systems for facial nerve paralysis have been developed to complement or improve upon the House-Brackmann grading system.

Sunnybrook Facial Grading System:

The Sunnybrook system evaluates facial function based on three components: resting symmetry, voluntary movement, and synkinesis. It provides a composite score ranging from 0 (complete paralysis) to 100 (normal function). This system is noted for its repeatability and minimal variability between observers, making it a reliable choice in clinical settings. It has been validated in various populations and is increasingly being adopted due to its comprehensive nature and responsiveness to treatment changes. [40]

Facial Motor Evaluation (FAME) Scale:

The FAME scale is a graphic facial nerve grading tool that assesses paralysis across different regions of the face. It incorporates both the severity of facial weakness and associated complications such as synkinesis and hyperkinesis. The FAME scale uses a scoring range from 0 to 24, categorizing severity into five levels: normal (0), mild (1-6), moderate (7-12), severe (13-18), and profound weakness (19-24). This scale has shown excellent inter-rater reliability and sensitivity to clinical changes over time. [41]

Yanagihara's Unweighted Grading System:

This system assesses facial nerve function based on specific anatomical segments responsible for different facial movements. It provides a maximum score of 15, with higher scores indicating better function. [42]

Facial Nerve Grading System 2.0 (FNGS2.0):

An updated version of the House-Brackmann, the FNGS 2.0, incorporates a 4-point scale for different regions (brow, eye, nasolabial fold, and oral) to account for synkinesis or involuntary muscle movements, providing more detailed insights into specific areas affected by paralysis. It is a more structured approach for assessing partial or regional dysfunction and synkinesis in a standardized way. [43]

Sydney Classification:

This system assesses the anatomical segments of the facial nerve responsible for each action, with a maximum score of 15 indicating normal function. [40]

Forehead, Eye, Mouth, and Associated Defect (FEMA) grading scale: FEMA uses a separate grade for each facial region and incorporates synkinesis to reduce subjective bias, enabling a clearer comparison of regional dysfunction. [44]

eFACE and auto-eFACE: The eFACE tool includes both static and dynamic assessments across the face, quantifying each facial region on a 0-100 scale. Auto-eFACE is an automated system using machine learning to assess and score paralysis objectively, which reduces observer bias and offers an efficient, standardized approach for clinical and research purposes. [45]

Treatments for facial nerve paralysis aim to restore function and symmetry. Physical therapy, medications (such as corticosteroids for Bell's palsy), and botox injections are commonly used, with surgical interventions for severe cases. Rehabilitative approaches often focus on improving muscle coordination, managing synkinesis, and addressing the physical and emotional impacts of facial asymmetry. For persistent cases, surgical options include brow lifts, eyelid weights for eye closure, and static slings to address sagging tissues, each tailored to the individual's needs. Rehabilitation often emphasizes exercises, relaxation techniques, and compensatory strategies to restore as much facial symmetry and function as possible. [46]

Vascular Supply of the Facial Nerve

The cortical motor area of the face is supplied by the artery of the central sulcus (Rolandic artery) from the middle cerebral artery.

Within the pons, the facial nucleus receives its blood supply primarily from the AICA. The AICA, a branch of the basilar artery, enters the internal acoustic meatus (IAC) with the facial nerve. The AICA branches into the labyrinthine and cochlear arteries.

As the facial nerve traverses through the internal auditory canal, it is supplied by branches from the AICA. The petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery also contributes to this supply, particularly within the facial canal. [1, 47]

After exiting the IAC through the stylomastoid foramen, the main arterial supply shifts to branches from the stylomastoid artery. In addition, within the parotid gland, blood supply is provided by branches from both the transverse facial artery and the superficial temporal artery, along with contributions from either the occipital artery or posterior auricular artery. [1, 47]

The superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery is the second of three sources of arterial blood supply to the extramedullary (i.e., intrapetrosal) facial nerve. The posterior auricular artery supplies the facial nerve at and distal to the stylomastoid foramen. Venous drainage parallels the arterial blood supply.

Anatomical studies have highlighted the variations in vascular loops formed by AICA that can compress cranial nerves, including CN VII (facial nerve), leading to clinical conditions such as hemifacial spasm or tinnitus. Understanding these vascular relationships is vital for surgical planning and management of conditions affecting cranial nerves. [48]

-

The surgical anatomy and landmarks of the facial nerve.

-

This homunculus illustrates the location on the motor strip of facial areas relative to the hand and upper extremities. The lower half of the figure depicts the anatomy of the pyramidal system.

-

This drawing shows the contents of the right internal acoustic meatus. Note the relationship between the nervus intermedius (ie, nerve of Wrisberg) and the facial nerve. Also note the superior location of the facial nerve relative to the vestibulocochlear nerve.

-

Schematic illustration shows the facial nerve and its peripheral connections. Note the interconnections of cranial nerve (CN) VII with CN V, CN IX, and CN X.

-

Spatial anatomic relationship between the nerves traveling through the internal acoustic meatus is shown. Note the changing spatial relationship between the facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII) and the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII). IAC = internal auditory canal (acoustic meatus); CPA = cerebellopontine angle

-

The transtemporal course of the facial nerve is shown. Note the vascular arcades feeding the facial nerve throughout its course in the bony facial canal.

-

Exposure of the facial nerve after a cortical mastoidectomy. The facial recess has been opened by thinning of the posterior canal wall. The recess is identified using the incus, chorda tympani, and horizontal semicircular canal as landmarks.