Overview

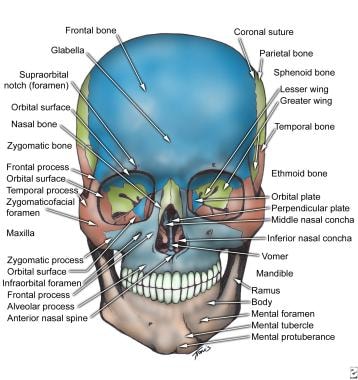

The facial skeleton serves to protect the brain, house and protect the sense organs of smell, sight, and taste, and provide a framework for the soft tissues of the face to facilitate eating, facial expression, breathing, and speech. It forms the anterior part of the skull and includes the mandible, maxilla, frontal bone, nasal bones, and zygoma as the primary bones. [1] Facial bone anatomy is complex yet elegant in its suitability to serve a multitude of functions. The image below provides an overview of the anterior features of the skull. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Mandible

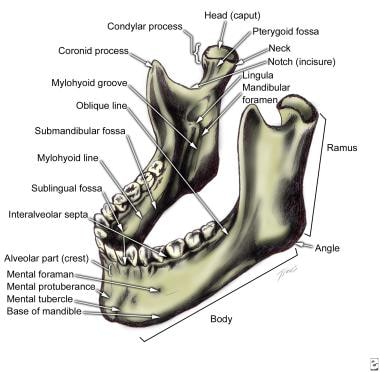

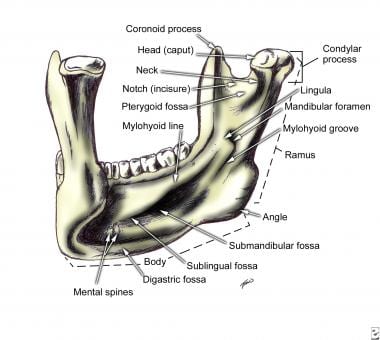

The mandible is a U-shaped bone. It is the only mobile bone of the facial skeleton, and since it houses the lower teeth, its motion is essential for mastication and speech. [8] It is formed by intramembranous ossification. The mandible is composed of two hemimandibles joined at the midline by a vertical symphysis. The hemimandibles fuse to form a single bone by the age of 2 years. Each hemimandible is composed of a horizontal body with a posterior vertical extension termed the ramus (see the images below). [9] The mandible has unique biomechanical properties due to its high collagen content and specific bone mineral density, which provide it with the flexibility to withstand daily mechanical stresses. [8]

Body - lateral surface

On the anterior inferior midline region of the hemimandible body is a triangular thickening of bone termed the mental protuberance, which forms the prominent chin area. [1] The thickened inferior rim of the mental protuberance extends laterally from the midline and forms two rounded protrusions termed the mental tubercles. They provide structural support to the chin and are palpable landmarks on the mandible. [1] Located lateral to the midline on the external surface are the mental foramina, which transmit the mental nerves and vessels. They usually are located below the apex of the second bicuspid and have 6-10 mm of variation in the anteroposterior dimension.

The rim of bone lateral to the mental tubercles extends posteriorly and ascends obliquely as the oblique line to join the anterior edge of the coronoid process. This line serves as an attachment for muscles such as the depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris, which are involved in facial expressions. [1] The inferior rim of the posterior body thickens and flares laterally where it attaches to the masseter muscle, one of the primary muscles of mastication, contributing to jaw movement and strength. [1]

Body - medial surface

Just lateral to the symphysis on the inner surface of the mandible are two paired protuberances termed the superior and inferior mental spines. The genioglossus muscle (aids in tongue movement) attaches to the superior mental spines, and the geniohyoid muscle (involved in elevating the hyoid bone and drawing it anteriorly) attaches to the inferior mental spines. [1, 10]

Just lateral to the inferior mental spines on the inferior border of the mandible are two concavities called the digastric fossae, where the anterior digastric muscles attach.

Extending obliquely in a posterosuperior direction from the midline is a ridge of bone called the mylohyoid line, which serves as the attachment site for the mylohyoid muscle. Above and below the mylohyoid line on the inner mandibular body are two shallow convexities, against which the sublingual and submandibular glands abut, respectively. Medial to the ascending edge of the anterior ramus is the retromolar trigone, located immediately behind the third molar.

Rami - lateral surface

The ramus extends vertically in a posterosuperior direction, posterior to the body on each hemimandible. The mandibular angle is formed by the intersection of the inferior rim of the body and the posterior rim of the ascending ramus. The superior ramus bifurcates into an anterior coronoid process and a posterior condylar process. The concavity between the two processes is called the mandibular notch. The coronoid is thin and triangular. With the teeth in occlusion, its superior extent is medial to the zygomatic arch. The coronoid is the site of attachment of the temporalis muscle. Inferiorly, the condylar process has a narrow neck that widens to a globular head that articulates with the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone, forming the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The lateral surface of the ramus provides an attachment site for the masseter muscle. [1]

Rami - medial surface

On the medial surface of the ramus, just below the mandibular notch, is an aperture termed the mandibular foramen; the inferior alveolar nerve and blood vessels run through this aperture. This foramen is typically located at the center of the medial surface of the ramus, slightly below the mandibular notch, often below the occlusal plane, serving as an entry point into the mandibular canal. [1, 11]

Just medial to the mandibular foramen is the lingula, a triangular bony protuberance with its apex pointing posterosuperiorly toward the condylar head. The lingula serves as an attachment point for the sphenomandibular ligament. Its position can vary, which has implications for surgical procedures such as mandibular nerve blocks. [12]

Extending anteriorly and inferiorly from the mandibular notch toward the inferior rim of the body is the mylohyoid groove, through which the mylohyoid nerve runs. The mylohyoid nerve, a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, provides motor innervation to the mylohyoid muscle and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. The morphology of the mylohyoid groove can vary significantly; it may be doubled, narrowed, or in some cases, covered by a bony bridge. These anatomical variations are clinically significant, especially in dental procedures and surgeries involving the mandible. [13]

Internal anatomy

The mandible has a large medullary core with a cortical rim that is 2-4 mm thick. [14] The inferior alveolar canal begins at the mandibular foramen and courses inferiorly, anteriorly, and toward the lingual surface in the ramus. In adults, the canal comes in close proximity to the roots of the third molar. In the mandibular body, the canal courses along the inferior border close to the lingual surface. Anteriorly, the canal runs typically inferior to the level of the mental foramen, to which it ascends at its terminal end.

The mandible houses the lower dentition, which in adults consists of two central and two lateral incisors, two canines, two first and two second premolars, and three sets of molars. Interdental septa run between the buccal and lingual cortices of the mandible, and interradicular septa run between the mesial and distal roots of the molars.

Maxilla

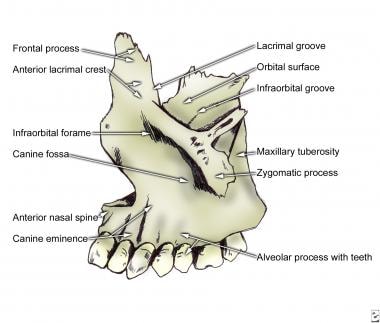

The maxilla has several roles. It houses the teeth, forms the roof of the oral cavity, forms the floor of and contributes to the lateral wall and roof of the nasal cavity, houses the maxillary sinus, and contributes to the inferior rim and floor of the orbit. Two maxillary bones are joined in the midline to form the middle third of the face (see the image below).

Anterior surface

In the midline of the anterior surface of the maxilla is found a prominence called the anterior nasal spine, with a lateral concave rim, called the nasal notch, which forms the floor of the piriform aperture. The anterior nasal spine plays a crucial role in supporting the nasal tip and influencing the nasolabial angle. The nasal notch contributes to the shape and size of the nasal cavity. [1]

Inferiorly, the alveolar process of the maxilla houses the teeth, including central incisors, lateral incisors, canines, two premolars, and three molars in adults. The tooth roots form vertical, wavelike eminences in the anterior face of the maxilla; the canine root is the most prominent. The canine root forms a vertical ridge, termed the canine eminence, in the anterior face of the maxilla. The shallow fossae medial and lateral to the canine eminence are called the incisive fossa and the canine fossa, respectively.

Infraorbital rim and frontal process

Superiorly, the maxillary bone is thickened in an inferior concavity that forms the infraorbital rim. Approximately 5-7 mm inferior to the rim lies the infraorbital foramen, which transmits the infraorbital nerve and vessels. There may be anatomic variations in the location of this foramen. The presence of accessory foramen (single/double) has also been reported. [15] The infraorbital rim extends medially and upward to form the frontal process of the maxilla.

The frontal process articulates superiorly with the frontal bone, medially with the nasal bone, and posteriorly with the lacrimal bone. This process plays a vital role in forming part of the lateral boundary of the nasal cavity and contributes to the stability of the nasal bridge. [16]

It has a smooth orbital surface that forms the vertical anterior lacrimal crest. Immediately posterior to the anterior lacrimal crest is a groove that forms the nasolacrimal canal.

Lateral portion

The maxilla projects laterally to form the zygomatic process, which articulates with the zygoma to form the lateral portion of the inferior orbital rim. Viewed medially, the maxillary sinus is evident with its medially facing ostium. The sinus is surrounded by several important structures, including the roots of the upper teeth inferiorly and the orbit superiorly. [17]

It articulates with the palatine bone posteriorly and with the ethmoid, lacrimal, and inferior concha bones medially.

In front of the maxillary sinus is a vertical nasolacrimal groove that forms the nasolacrimal canal with the lacrimal bone posteriorly and terminates inferiorly under the attachment of the inferior concha.

The maxilla undergoes intramembranous ossification and may exhibit variations such as accessory infraorbital foramina or septa within the maxillary sinus. These variations can have clinical implications, especially in surgical procedures involving the maxillary region. [17]

Superior surface

The superior surface of the maxilla forms the medial floor of the orbit.

Posteriorly, the free edge forms the anterior border of the inferior orbital fissure. This fissure is crucial for transmitting nerves and vessels between the orbit and surrounding areas. [1]

Medially, the orbital surface articulates with the ethmoid bone and lacrimal bone. These articulations help form part of the medial wall of the orbit. [1]

Behind the frontal process of the maxilla and its anterior lacrimal crest is the nasolacrimal groove. This groove is an essential part of the nasolacrimal system, which drains tears from the eye into the nasal cavity. [1]

Laterally, the orbital surface articulates with the orbital surface of the zygoma. This articulation helps form part of the lateral wall and rim of the orbit. [1]

On its inferior surface, the maxilla has a horizontal palatine process that forms the bulk of the hard palate.

The palatine processes of both maxillae articulate with each other in the midline and with the horizontal plate of the palatine bone posteriorly.

Anteriorly in the midline articulation of both palatine processes is the incisive canal, which transmits the nasopalatine nerve and branches of the greater palatine vessels. From a medial view, the maxillary hiatus is evident, opening into the maxillary sinus that occupies the predominant portion of the body of the maxilla.

Zygoma

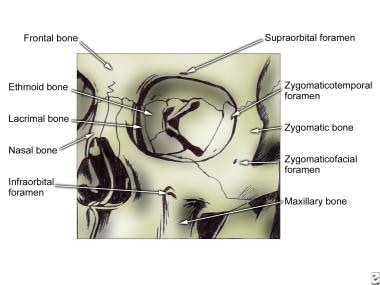

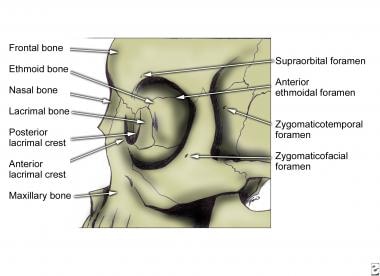

The zygoma forms the lateral portion of the inferior orbital rim, as well as the lateral rim and lateral wall of the orbit. Additionally, it forms the anterior zygomatic arch, from which the masseter muscle is suspended (see the images below).

The masseter muscle acts to close the mandible for mastication and speech. On its lateral surface, the zygomatic bone has three processes. Inferiorly, a concave process projects medially to articulate with the zygomatic process of the maxilla, forming the lateral portion of the infraorbital rim. This concavity projects superiorly to form the frontal process that articulates with the frontal bone.

Posteriorly, a temporal process articulates with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to form the zygomatic arch. On the medial surface of the zygoma is a smooth orbital plate that forms the lateral floor and lateral wall of the orbit. It articulates posteriorly with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone.

Just posterior to the lateral rim and slightly inferior to the frontozygomatic suture is the marginal tubercle of Whitnall, to which the lateral palpebral ligament attaches. On the smooth medial orbital surface are foramina, which transmit the zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal nerves to their respective apertures on the lateral surface. The zygomaticofacial foramen is located just lateral to the lateral orbital rim at the junction of the frontal and maxillary processes. The zygomaticotemporal foramen is located on the posterior concave surface of the lateral orbital rim. [18]

Frontal Bone

Anterior surface

The frontal bone forms the anterior portion of the cranium, houses the frontal sinuses, and forms the roof of the ethmoid sinuses, nose, and orbit.

Anteriorly, the external surface is convex superiorly, and it articulates with the parietal bones posteriorly and the greater wing of the sphenoid posteroinferiorly. The anterior convex surface thickens inferiorly to form the supraorbital rims. Just above the supraorbital rims are thickened arches termed the superciliary arches. Their midline union forms a depression called the glabella. At the junction of the lateral third and the medial third of each supraorbital rim is either a notch or foramen through which the supraorbital vessels and nerves run. Bilateral notches are found in 49% of skulls, bilateral foramina in 26%, and one notch and one foramen in 24%. [19]

Inferolaterally, the supraorbital ridge forms the zygomatic process that articulates with the frontal process of the zygomatic bone. The inferior surface of the frontal bone forms the concave surface of the orbital roof and the anterior nasal roof.

Orbital surface

The orbital surface articulates posteriorly with the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid bone, medially with the ethmoid, lacrimal, and maxillary bones, and laterally with the zygoma. On the anterolateral orbital surface is a poorly developed depression for the lacrimal gland. On the medial orbital surface is a small mound where the cartilaginous trochlea of the superior oblique muscle attaches. The medial border of each orbital surface is separated by the ethmoidal notch, which houses the ethmoidal air cells. [1] Anteriorly, between the orbital surfaces, the frontal bone articulates with the anterior portions of the nasal bones and frontal processes of the maxilla. A small, vertical midline plate, termed the nasal spine of the frontal bone, contributes to the nasal septum. [20]

Internal surface

The internal surface of the frontal bone is concave anteriorly, with grooves laterally for the middle meningeal vessels. The floor of the internal surface forms the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. It has a midline dehiscence termed the ethmoid notch that articulates with the ethmoid bone (see the image below). Anterior to the ethmoid notch is an upward-sloping ridge termed the frontal crest, which forms a groove for the superior sagittal sinus. At the anterior articulation between the frontal crest and the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone is a small foramen called the foramen caecum, which usually transmits an emissary vein from the roof of the nasal cavity to the superior sagittal sinus. Foramen caecum can vary in size and may sometimes not be patent. [21]

Additionally, the frontal crest serves as an attachment point for the falx cerebri, a dural fold that separates the two cerebral hemispheres. [22]

Frontal sinus

The frontal sinus is one of the four paranasal sinuses. [23] The frontal sinus begins to form after the age of 3.5 years and becomes radiographically visible around 4 years of age. Its growth continues with craniofacial development, reaching peak expansion by approximately 18 years of age. [23]

The frontal sinuses are paired, air-filled cavities located in the frontal bone, posterior to the superciliary arches. [1] It is located in the anterior midline, between the supraorbital rims. The sinuses are typically triangular in shape and are lined with a mucous membrane that aids in warming and humidifying inhaled air. [1, 24]

In adults, the average dimensions reach 2.4 mm high, 2.9 cm to either side from the midline, and 2 cm in the anteroposterior dimension. The average dimensions of a frontal sinus can vary significantly due to individual anatomical differences. The variability in size can be influenced by factors such as craniofacial patterns and skeletal malocclusions, with Class III malocclusions often associated with larger frontal sinuses. [25]

The anterior wall of the frontal bone splits to enclose the sinus, but the anterior and posterior walls retain their diploë. The frontal sinus usually is divided sagittally by a frequently eccentric septum. Just lateral to the midline, the bone of the anterior wall of the sinus is 4 mm thick, and the bone of the posterior wall is 1.9 mm thick.

The frontal sinuses drain into the anterior part of the corresponding middle meatus of the nasal cavity via the frontonasal duct. [1]

Nasal Bones

The paired nasal bones form the anterosuperior bony roof of the nasal cavity. They are approximately quadrangular. They articulate with the nasal process of the frontal bone superiorly, the frontal process of the maxillary bone laterally, and with one another medially. Their inferior border is free and forms the superior margin of the piriform aperture. The external surface is convex except for the superior-most portion, where a concavity forms as the margin turns superiorly to articulate with the frontal bone. On the internal surface is a vertical groove for the external nasal artery.

-

Skull, anterior view.

-

Mandible, anterolateral superior view.

-

Mandible, left posterior view.

-

Left maxilla.

-

Zygoma, frontal view.

-

Zygoma, lateral view.

-

Frontal bone, inferior and posterior aspects.