Practice Essentials

Obesity is a substantial public health crisis in the United States and internationally, with the prevalence increasing rapidly in numerous industrialized nations. [1] According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), between 2017 and March 2020, the U.S. obesity rate in children and adolescents aged 2-19 years was 19.7%. [2] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that in 2023, adult obesity rates in 23 US states were 35% or higher, with the rate being at least 20% for all states. Prior to 2013, the adult obesity rate in no state reached 35%. [3]

The image below details the comorbidities of obesity.

Signs and symptoms

Among several classifications and definitions for degrees of obesity, the following is widely used [4] :

-

Overweight - Body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 25 to 29.9 kg/m2

-

Obesity class I - BMI 30 to 34.9 kg/m2

-

Obesity class II - BMI 35 to 39.9 kg/m2

-

Obesity class III - BMI greater than or equal to 40 kg/m2 (also termed severe, extreme, or massive obesity)

Some authorities advocate a definition of obesity based on percentage of body fat, as follows:

-

Men: Percentage of body fat greater than 25%, with 21-25% being borderline

-

Women: Percentage of body fat greater than 33%, with 31-33% being borderline

The clinician should also determine whether the patient has had any of the comorbidities related to obesity, including the following [5] :

-

Malignant - Reported association with endometrial (premenopausal), colon (in men), rectal (in men), breast (postmenopausal), gallbladder, gastric cardial, pancreatic, ovarian, renal, liver, and thyroid cancer, as well as with malignant meningioma, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and multiple myeloma [8, 9, 10, 11]

-

Psychological - Social stigmatization and depression

-

Cardiovascular - Coronary artery disease, [12] essential hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, cor pulmonale, obesity-associated cardiomyopathy, accelerated atherosclerosis, and pulmonary hypertension of obesity

-

Central nervous system (CNS) - Stroke, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and meralgia paresthetica

-

Obstetric and perinatal - Pregnancy-related hypertension, fetal macrosomia, and pelvic dystocia [13]

-

Surgical - Increased surgical risk and postoperative complications, including wound infection, postoperative pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism

-

Pelvic - Stress incontinence

-

Gastrointestinal (GI) - Gallbladder disease (cholecystitis, cholelithiasis), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fatty liver infiltration, and reflux esophagitis

-

Orthopedic - Osteoarthritis, coxa vera, slipped capital femoral epiphyses, Blount disease, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, and chronic lumbago

-

Metabolic - Type 2 diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia

-

Reproductive (in women) - Anovulation, early puberty, infertility, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries

-

Reproductive (in men) - Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

-

Cutaneous - Intertrigo (bacterial and/or fungal), acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, and increased risk for cellulitis and carbuncles

-

Extremity - Venous varicosities, lower extremity venous and/or lymphatic edema

-

Miscellaneous - Reduced mobility and difficulty maintaining personal hygiene

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies

-

Fasting lipid panel

-

Liver function studies

-

Thyroid function tests

-

Fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

Evaluation of degree of body fat

BMI calculation, waist circumference, and waist/hip ratio are the common measures of the degree of body fat used in routine clinical practice. Other procedures that are used include the following:

-

Caliper-derived measurements of skin-fold thickness

-

Dual-energy radiographic absorptiometry (DXA)

-

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

-

Ultrasonography to determine fat thickness

-

Underwater weighing

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of obesity starts with comprehensive lifestyle management (ie, diet, physical activity, behavior modification). [14] The 3 major phases of any successful weight-loss program are as follows:

-

Preinclusion screening phase

-

Weight-loss phase

-

Maintenance phase - This can conceivably last for the rest of the patient's life but ideally lasts for at least 1 year after the weight-loss program has been completed

Medications

Currently, the three major groups of drugs used to manage obesity are as follows:

-

Centrally acting medications that impair dietary intake

-

Medications that act peripherally to impair dietary absorption

-

Medications that increase energy expenditure

Setmelanotide is the first drug approved for weight management in patients with rare genetic conditions (ie, proopiomelanocortin [POMC], proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 [PCSK1], leptin receptor [LEPR] deficiencies).

Several glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists (liraglutide, semaglutide, tirzepatide) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for chronic weight management.

Surgery

Among the standard bariatric procedures are the following:

-

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

-

Adjustable gastric banding

-

Gastric sleeve surgery

-

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy

-

Horizontal gastroplasty

-

Vertical banded gastroplasty

-

Duodenal-switch procedures

-

Biliopancreatic bypass

-

Biliopancreatic diversion

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The growing rate of obesity internationally represents a pandemic that needs urgent attention if obesity’s potential toll on morbidity, mortality, and economics is to be avoided. Research into the complex physiology of obesity may aid in avoiding this impact. (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.)

A study by Ward et al indicated that in the United States, adult obesity accounts for $172.74 billion in medical costs per year (in 2019 dollars), with annual per-person medical costs being $1861 higher as a result of obesity. [15]

In a 2016 position statement, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) and the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) proposed a new name for obesity, adiposity-based chronic disease (ABCD). The AACE/ACE did not introduce the name as an actual replacement for the term obesity but instead as a means of helping the medical community focus on the pathophysiologic impact of excess weight. [16]

Such impact also figured into a report issued in January 2025 by the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology Commission, overhauling the definition of obesity into clinical and preclinical designations. The commission defined obesity in general as being characterized "by excess adiposity, with or without abnormal distribution or function of adipose tissue, and with causes that are multifactorial and still incompletely understood.” Clinical obesity, however, was defined as a “chronic, systemic illness [characterized] by alterations in the function of tissues, organs, the entire individual, or a combination thereof, due to excess adiposity.” Clinical obesity, as the commission categorized it, “can lead to severe end-organ damage, causing life-altering and potentially life-threatening complications (eg, heart attack, stroke, and renal failure).” [17]

Preclinical obesity, as defined by the commission, is “a state of excess adiposity with preserved function of other tissues and organs and a varying, but generally increased, risk of developing clinical obesity and several other non-communicable diseases (eg, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, certain types of cancer, and mental disorders).” [17]

Clinical obesity, therefore, was defined by the commission as a disease, while preclinical obesity, although considered a health risk, was not itself categorized as an illness. [17, 18]

The commission further recommended that BMI be used not as a measure of health for individual patients, but instead “only as a surrogate measure of health risk at a population level, for epidemiological studies, or for screening purposes.” [17]

For information on pediatric obesity, see Obesity in Children.

Measurements of obesity

Obesity represents a state of excess storage of body fat, while the term "overweight" is puristically defined as an excess of body weight for height. Normal, healthy men have a body fat percentage of 15-20%, while normal, healthy women have a percentage of approximately 25-30%. [19] However, because differences in weight among individuals are only partly the result of variations in body fat, body weight is a limited, although easily obtained, index of obesity.

The body mass index (BMI), also known as the Quetelet index, is used far more commonly than body fat percentage to define obesity. In general, BMI correlates closely with the degree of body fat in most settings; however, this correlation is weaker at low BMIs.

An individual’s BMI is calculated as weight/height2, with weight being in kilograms and height being in meters (otherwise, the equation is weight in pounds ´ 0.703/height in inches2). Online BMI calculators are available.

A person’s body fat percentage can be indirectly estimated by using the Deurenberg equation, as follows:

body fat percentage = 1.2(BMI) + 0.23(age) - 10.8(sex) - 5.4

with age being in years and sex being designated as 1 for males and 0 for females. This equation has a standard error of 4% and accounts for approximately 80% of the variation in body fat.

Although the BMI typically correlates closely with percentage body fat in a curvilinear fashion, some important caveats apply to its interpretation. In mesomorphic (muscular) persons, BMIs that usually indicate overweight or mild obesity may be spurious, whereas in some persons with sarcopenia (eg, elderly individuals and persons of Asian descent, particularly from South Asia), a typically normal BMI may conceal underlying excess adiposity characterized by an increased percentage of fat mass and reduced muscle mass.

In view of these limitations, some authorities advocate a definition of obesity based on percentage of body fat. For men, a percentage of body fat greater than 25% defines obesity, with 21-25% being borderline. For women, over 33% defines obesity, with 31-33% being borderline.

Other indices used to estimate the degree and distribution of obesity include the 4 standard skin thicknesses (ie, subscapular, triceps, biceps, suprailiac) and various anthropometric measures, of which waist and hip circumferences are the most important. Skinfold measurements are the least accurate means by which to assess obesity.

Dual-energy radiographic absorptiometry (DXA) scanning is used primarily by researchers to accurately measure body composition, particularly fat mass and fat-free mass. It has the additional advantage of measuring regional fat distribution. However, DXA scans cannot be used to distinguish between subcutaneous and visceral abdominal fat deposits.

The current standard techniques for measuring visceral fat volume are abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning (at L4-L5) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques. A simpler technique, using bioelectrical impedance, also exists; [20] however, this method is generally limited to clinical research.

Classification of obesity

Among several classifications and definitions for degrees of obesity, the following is widely used:

-

Overweight - BMI greater than or equal to 25 to 29.9 kg/m2

-

Obesity class I - BMI 30 to 34.9 kg/m2

-

Obesity class II - BMI 35 to 39.9 kg/m2

-

Obesity class III - BMI greater than or equal to 40 kg/m2 (also termed severe, extreme, or massive obesity)

Under this classification, the cutoff points differ for Asian and South Asian populations, with overweight being classified as 23-24.9 kg/m2, and obesity as 25 kg/m2 or greater.

In children, a BMI above the 85th percentile (for age-matched and sex-matched control subjects) is commonly used to define overweight, and a BMI above the 95th percentile is commonly used to define obesity.

Comorbidities associated with obesity

Obesity is associated with a host of potential comorbidities that significantly increase the risk of morbidity and mortality in obese individuals. Although no cause-and-effect relationship has been clearly demonstrated for all of these comorbidities, amelioration of these conditions after substantial weight loss suggests that obesity probably plays an important role in their development. (See Presentation.)

Apart from total body fat mass, the following aspects of obesity have been associated with comorbidity:

-

Fat distribution

-

Waist circumference

-

Age of obesity onset

-

Intra-abdominal pressure

Fat distribution

Accumulating data suggest that regional fat distribution substantially affects the incidence of comorbidities associated with obesity. [5] Android obesity, in which adiposity is predominantly abdominal (including visceral and, to a lesser extent, subcutaneous), is strongly correlated with worsened metabolic and clinical consequences of obesity.

Waist circumference

The thresholds used in the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III definition of metabolic syndrome [21] state that significantly increased cardiovascular risk (metabolic central obesity) exists in men with waist circumferences of greater than 94 cm (37 in) and in women with waist circumferences of greater than 80 cm (31.5 in), as well as waist-to-hip ratios of greater than 0.95 (in men) or of more than 0.8 (in women). Circumferences of 102 cm (40 in) in men and 88 cm (35 in) in women indicate a markedly increased risk requiring urgent therapeutic intervention.

These thresholds are much lower in Asian populations. After analyzing survey results of Chinese, Malay, and Asian-Indian cohorts, Tan and colleagues concluded that a waist circumference of greater than 90 cm in men and of more than 80 cm in women were more appropriate criteria for metabolic central obesity in these ethnic groups. [22]

Age of obesity onset

An elevated BMI during adolescence (starting within the range currently considered normal) is strongly associated with the risk of developing obesity-related disorders later in life, independent of adult BMI. [23] Increases in BMI during early adulthood (age 25-40 y) are associated with a worse profile of biomarkers related to obesity than are BMI increases during later adulthood. [24] This is consistent with most emerging data regarding timing of changes in BMI and later health consequences.

Intra-abdominal pressure

Apart from the metabolic complications associated with obesity, a paradigm of increased intra-abdominal pressure has been recognized. This pressure effect is most apparent in the setting of marked obesity (BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2) and is espoused by bariatric surgeons. [25]

Findings from bariatric surgery and animal models suggest that this pressure elevation may play a role (potentially a major one) in the pathogenesis of comorbidities of obesity, such as the following [26] :

-

Pseudotumor cerebri

-

Lower-limb circulatory stasis

-

Ulcers

-

Dermatitis

-

Thrombophlebitis

-

Reflux esophagitis

-

Abdominal hernias

-

Possibly, hypertension and nephrotic syndrome

Osteoarthritis

A study by Losina et al found that obesity with knee osteoarthritis resulted in the loss of a substantial number of quality-adjusted life years. The association was most notable among Black and Hispanic women. [27]

Focal glomerulosclerosis

Some reports, including those by Adelman and colleagues and by Kasiske and Jennette, suggest an association between severe obesity and focal glomerulosclerosis. [28, 29, 30] This complication, in particular, improves substantially or resolves soon after bariatric surgery, well before clinically significant weight loss is achieved.

Pickwickian syndrome

The so-called Pickwickian syndrome is a combined syndrome of obesity-related hypoventilation [7] and sleep apnea. It is named after Charles Dickens’s novel The Pickwick Papers, which contains a character with obesity who falls asleep constantly during the day.

The hypoventilation in Pickwickian syndrome results from severe mechanical respiratory limitations to chest excursion, caused by severe obesity. The sleep apnea may be from obstructive and/or central mechanisms. Obstructive sleep apnea is common among men with collar size greater than 17 in (43 cm) and women with collar size greater than 16 in (41 cm).

Increased and decreased sleep duration

Sleep duration of less than 5 hours or more than 8 hours was associated with increased visceral and subcutaneous body fat, in a study of young African Americans and Hispanic Americans. [31] This association relates mostly to decreased leptin hormone and increased ghrelin hormone levels. [32]

COVID-19

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) includes obesity in the list of conditions that increase the likelihood of severe illness in persons with COVID-19. [33]

A report released in March 2021 by the World Obesity Federation stated that the mortality risk from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is about 10 times higher in countries where more than 50% of the adult population is classified as overweight. Of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% were found to have occurred in countries where the majority of adults were overweight. [34, 35]

A study reported that out of 178 adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19, at least one underlying condition was found in 89.3%, the most common being hypertension (49.7%), obesity (48.3%), chronic lung disease (34.6%), diabetes mellitus (28.3%), and cardiovascular disease (27.8%). Moreover, obesity was the most prevalent underlying condition among patients aged 18-64 years. [36]

In addition, a report by Lighter et al, based on data from a large academic hospital system in New York City, indicated that in persons under age 60 years, obesity increases the risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 two-fold, with such patients also being more likely to require intensive care. [37, 38]

A study by Kass et al indicated that among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), there is a greater tendency for younger individuals to have obesity, with age inversely correlated with BMI. [39, 40]

A relationship between obesity and progression to severe COVID-19 status was also seen in studies by Cai et al and Gao et al, with the Cai study indicating that the odds ratio (OR) of persons with obesity progressing to severe disease is 3.4, and the Gao study finding the progression to severe or critical COVID-19 status to be threefold greater in patients with obesity. [41, 42, 43]

A study by Foulkes et al indicated that severe COVID-19 outcomes in persons with obesity can be linked to obesity-associated systemic inflammation, particularly in patients under age 65 years. The phenomenon reportedly was evidenced by the peak circulating C-reactive protein levels in individuals with obesity. [44]

A study from the CDC of adults with COVID-19 reported that BMI has a nonlinear (J-shaped) relationship with COVID-19 severity. With regard to ICU admission, the risk was indicated to be 6% greater in patients with a BMI of 40-44.9 kg/m2, rising to 16% greater in association with a BMI of 45 kg/m2 or higher. The mortality risk in adults with obesity was 8% greater in patients with a BMI of 30-34.9 kg/m2, rising to 61% higher with a BMI of 45 kg/m2 or more. The results also indicated that patients under age 65 years with obesity are at particular risk for hospitalization and death due to COVID-19. In addition, the study found that people who are underweight also have a greater risk for hospital admission due to COVID-19, with the likelihood being 20% higher in persons with a BMI below 18.5 kg/m2, compared with individuals with a healthy BMI. [45, 46]

A study by Gao et al indicated that there is a linear increase in the risk for severe outcomes in COVID-19 as an individual’s BMI rises past 23 kg/m2, with the risk turning upward even in light of a small rise in body mass. Moreover, this phenomenon appears to be independent, being unassociated with the presence of diabetes and other diseases related to obesity. Additionally, similar to the above CDC study, the investigators found the relationship between body mass and hospitalization from COVID-19 to be J-shaped, observing that patients with BMIs at or below 20 kg/m2 were also at increased risk. It was determined as well that for persons in the study between age 20 and 39 years, the risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization for increases in BMI above 23 kg/m2 was greater than for patients aged 80-100 years, while the risk of hospitalization and death in association with increased BMI was higher for Black persons than for White ones. [47, 48]

A study from England, by Szatmary et al, suggested that young men with overweight or obesity who have COVID-19 may be at particular risk for developing pancreatitis. [49, 50]

A study by Guerson-Gil et al indicated that in hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19 and obesity, men have a significantly greater likelihood of in-hospital death than do women. The investigators found, for example, that in patients with a BMI of 35-39.9 kg/m2, the odds ratios (ORs) for mortality in the study were 1.0 and 1.99 for women and men, respectively, while for those with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or above, the ORs were 1.72 and 2.26, respectively. [51, 52]

An international study reported that after older age and male sex, obesity is the greatest risk factor for severe pneumonia, that is, pneumonia requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, in ICU patients with COVID-19. BMI was found to have a linear correlation with the need for such ventilation, with obesity’s highest impact seen in women under age 50 years. [53]

Research also indicates that patients with obesity are more likely to suffer from long COVID-19 (ie, long-term complications associated with COVID-19). A study by Aminian et al looked at patients who required no intensive care unit (ICU) admission during the acute phase of COVID-19, with the study's follow-up period lasting 10 months. (This follow-up began after the initial 30-day period subsequent to a positive test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2], the virus that causes COVID-19.) During follow-up, persons with moderate or severe obesity had a 28% and 30% greater risk of hospital admission, respectively, than did patients with a normal BMI. In addition, the need for diagnostic tests to evaluate for various medical conditions (including tests of the heart, lung, and kidney and for gastrointestinal or hormonal symptoms, blood disorders, and mental health problems) was increased by 25% and 39%, respectively. [54, 55]

Additional comorbidities

Individuals with overweight or obesity are at increased risk for the following health conditions:

-

Metabolic syndrome

-

Type 2 diabetes

-

Hypertension

-

Dyslipidemia

-

Coronary heart disease

-

Osteoarthritis

-

Stroke

-

Depression

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

-

Infertility (women) and erectile dysfunction (men)

-

Gallbladder disease

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

-

Asthma

A study by Cameron et al indicated that in the United States between 2013 and 2016, obesity was responsible for the development of new-onset diabetes in 41% of adults. The highest attributable rate of obesity-related diabetes was among non-Hispanic White women (53%); non-Hispanic Black men demonstrated the lowest rate, with the attributable fraction being 30%. [58, 59]

A study by Abdullah et al indicated that not only the severity of a patient’s obesity but its duration as well is associated with the individual’s risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Based on a more than four-decade follow-up of 5132 participants in the Framingham Offspring Study, the investigators found a significant rise in type 2 diabetes risk as obese-years increased. [60]

Research indicates that the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes is not the same in all persons with overweight or obesity, with some of these individuals being genetically inclined toward an adiposity profile that lowers their chances for the disease. Fourteen genetic variants have been identified that investigators say lead to subcutaneous storage of excess fat rather than accumulation of the fat around organs such as the liver, thus reducing the diabetes risk. [61]

A Korean study, by Evangelista et al, found a higher prevalence of general and abdominal obesity in persons with some stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) than in those without CKD. The greatest prevalence of these forms of obesity was found in patients with stage 2 CKD. The investigators also reported that general and abdominal obesity were not associated with stage 4 or 5 CKD. [62]

Pathophysiology

Hypertrophic versus hypercellular obesity

The adipocyte, which is the cellular basis for obesity, may be increased in size or number in obese persons. Hypertrophic obesity, characterized by enlarged fat cells, is typical of android abdominal obesity. Hypercellular obesity is more variable than hypertrophic obesity; it typically occurs in persons who develop obesity in childhood or adolescence, but it is also invariably found in subjects with severe obesity.

Hypertrophic obesity usually starts in adulthood, is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, and responds quickly to weight reduction measures. In contrast, patients with hypercellular obesity may find it difficult to lose weight through nonsurgical interventions.

Adipocytes

Products

The adipocyte is increasingly found to be a complex and metabolically active cell. At present, the adipocyte is perceived as an active endocrine gland producing several peptides and metabolites that may be relevant to the control of body weight; these are being studied intensively. [63]

Many of the adipocytokines secreted by adipocytes are proinflammatory or play a role in blood coagulation. Others are involved in insulin sensitivity and appetite regulation. However, the function of many of these identified cytokines remains unknown or unclear.

Proinflammatory products of the adipocyte include the following [64] :

-

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha

-

Interleukin 6

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 (MCP-1)

Other adipocyte products include the following [64] :

-

Lipotransin

-

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) - Associated with cardiovascular risk

-

Adipocyte lipid-binding protein

-

Acyl-stimulation protein

-

Prostaglandins - Coagulation role

-

Adipsin

-

Perilipins

-

Lactate

-

Leptin - Appetite regulator

-

Adiponectin - Major role in insulin sensitivity

-

Monobutyrin

-

Phospholipid transfer protein

Metabolism and function

Critical enzymes involved in adipocyte metabolism and function include the following:

-

Endothelial-derived lipoprotein lipase - Lipid storage

-

Hormone-sensitive lipase - Lipid elaboration and release from adipocyte depots

-

Acyl-coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) synthetases - Fatty acid synthesis

In addition, a cascade of enzymes is involved in beta-oxidation and fatty acid metabolism. The ongoing flurry of investigation into the intricacies of adipocyte metabolism has not only improved our understanding of the pathogenesis of obesity but has also offered several potential targets for therapy.

Development

Another area of active research is investigation of the cues for the differentiation of preadipocytes to adipocytes. The recognition that this process occurs in white and brown adipose tissue, even in adults, has increased its potential importance in the development of obesity and the relapse to obesity after weight loss.

Among the identified elements in this process are the following transcription factors:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor–gamma (PPAR-gamma)

-

Retinoid-X receptor ligands

-

Perilipin

-

Adipocyte differentiation–related protein (ADRP)

-

CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBP) alpha, beta, and delta

PPAR-gamma agonists increase the recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of preadipocytes (healthy fat) and cause apoptosis of hypertrophic and dysfunctional adipocytes (including visceral fat). This results in improved fat function and improved metabolic parameters associated with excessive fat–related metabolic diseases (EFRMD), including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. [65]

Hormonal influences on appetite

In addition to neurotransmitters and neurogenic signals, many hormones affect appetite and food intake. Endocannabinoids, through their effects on endocannabinoid receptors, increase appetite, enhance nutrient absorption, and stimulate lipogenesis. Melanocortin hormone, through its effects on various melanocortin receptors, modifies appetite.

Several gut hormones play significant roles in inducing satiety, including glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1), peptide YY (3-36) (PYY [3-36]), and cholecystokinin. Leptin and pancreatic amylin are other potent satiety hormones. On the other hand, ghrelin, which is secreted from the stomach fundus, is a major hunger hormone.

Odor detection threshold

Smell plays an important role in feeding behavior. Differences in the odor detection threshold (ie, the lowest concentration of a substance detectable by the human olfactory sense) were found in a study that measured thresholds in 8 lean, fasted individuals before and during a 2-hour hyperinsulinemic euglycemic insulin clamp. [66]

Increased insulin led to reduced smelling capacity, potentially reducing the pleasantness of eating. Therefore, insulin action in the olfactory bulb may be involved in the process of satiety and may be of clinical interest as a possible factor in the pathogenesis of obesity. [66]

Leptin

Friedman and colleagues discovered leptin (from the Greek word leptos, meaning thin) in 1994 and ushered in an explosion of research and a great increase in knowledge about regulation of the human feeding and satiation cycle. Leptin is a 16-kd protein produced predominantly in white subcutaneous adipose tissue and, to a lesser extent, in the placenta, skeletal muscle, and stomach fundus in rats. Leptin has myriad functions in carbohydrate, bone, and reproductive metabolism that are still being unraveled, but its role in body-weight regulation is the main reason it came to prominence.

Since this discovery, neuromodulation of satiety and hunger with feeding has been found to be far more complex than the old, simplistic model of the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus and limbic centers of satiety and the feeding centers of the lateral hypothalamus. Potentially, leptin sensitizers may assist in changing feeding habits.

The major role of leptin in body-weight regulation is to signal satiety to the hypothalamus and thus reduce dietary intake and fat storage while modulating energy expenditure and carbohydrate metabolism, preventing further weight gain. Unlike the Ob/Ob mouse model in which this peptide was first characterized, most humans with obesity are not leptin deficient but are instead leptin resistant. Therefore, they have elevated levels of circulating leptin. Leptin levels are higher in women than in men and are strongly correlated with BMI. [67]

Patients with night-eating syndrome have attenuation of the nocturnal rise in plasma melatonin and leptin levels and higher circadian levels of plasma cortisol. These individuals have morning anorexia, evening hyperphagia, and insomnia. In one study, patients with night-eating syndrome averaged 3.6 awakenings per night; 52% of these awakenings were associated with food intake, with a mean intake per ingestion of 1134 kcal. [68]

Genetics

Mutations resulting in defects of the leptin receptor in the hypothalamus may occur. These mutations result in early onset obesity and hyperphagia despite normal or elevated leptin levels, along with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and defective thyrotropin secretion.

Murray et al first reported on a sequence variant within the leptin gene that enhances the intrinsic bioactivity of leptin but which is associated with reduced weight rather than obesity. [69] This sequence variant within the leptin gene is also associated with delayed puberty.

Etiology

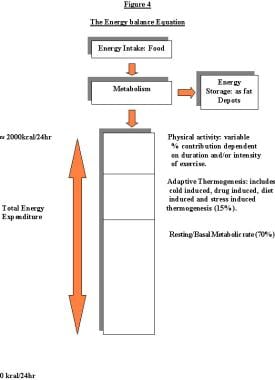

The etiology of obesity is far more complex than simply an imbalance between energy intake and energy output. Although this view allows easy conceptualization of the various mechanisms involved in the development of obesity, obesity is far more than simply the result of eating too much and/or exercising too little (see the energy-balance equation, below). Possible factors in the development of obesity include the following:

-

Metabolic factors

-

Genetic factors

-

Level of activity

-

Endocrine factors

-

Race, sex, and age factors

-

Ethnic and cultural factors

-

Socioeconomic status

-

Dietary habits

-

Smoking cessation

-

Pregnancy and menopause

-

Psychological factors

-

History of gestational diabetes

-

Lactation history in mothers

Nevertheless, the prevalence of inactivity in industrialized countries is considerable and relevant to the rise in obesity. The National Center for Health Statistics reported that in 2020, the rate of adults aged 18 years or older meeting the aerobic and muscle-strengthening recommendations outlined in the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans was 24.2%. [70, 71]

Although those same guidelines state that in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years, substantial benefits can be obtained through a total of 60 minutes or more per day of “moderate-to-vigorous physical activity,” with most of it aerobic, in 2017 only 26.1% of adolescents in the United States participated in 60 minutes or more of aerobic activity daily. [71, 72]

A study by Maripuu et al indicated that hypercortisolism associated with recurrent affective disorders increases the risk for metabolic disorders and cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, overweight, large waist, high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels. The study included 245 patients with recurrent depression or bipolar disorder and 258 controls. [73]

A study by Tester et al found that children with severe obesity (BMI at or above 120% of the 95th percentile) between ages 2 and 5 years were more likely to have the following characteristics [74] :

-

Be African American (odds ratio [OR]: 1.7) or Hispanic (OR: 2.3)

-

Engage in more than 4 hours of screen time (OR: 2.0)

-

Be from households characterized by a lower level of educational achievement (OR: 2.4)

-

Be from a single-parent household (OR: 2.0)

-

Be from a household living in poverty (OR: 2.1)

In addition, children in this age group who had never been breastfed were at higher risk of severe obesity (OR: 1.9). [74]

Genetics

Two major groups of factors, genetic and environmental, have a balance that variably intertwines in the development of obesity. Genetic factors are presumed to explain 40-70% of the variance in obesity, within a limited range of BMI (18-30 kg/m2).

A study in which monozygotic twins were overfed by 1000 kcal per day, 6 days a week, over a 100-day period found that the amount of weight gain varied significantly between pairs (4.3 to 13.3 kg). However, the similarity within each pair was significant with respect to body weight, percentage of fat, fat mass, and estimated subcutaneous fat, with about 3 times more variance among pairs than within them. [75] This observation indicates that genetic factors are significantly involved and may govern the tendency to store energy.

Heritability

The strong heritability of obesity has been demonstrated in several twin and adoptee studies, in which individuals with obesity who were reared separately followed the same weight pattern as that of their biologic parents and their identical twin. Metabolic rate, spontaneous physical activity, and thermic response to food seem to be heritable to a variable extent.

A study by Freeman et al found that having a father with overweight or obesity and a healthy-weight mother significantly increased the odds of childhood obesity; however, having a mother with obesity and a healthy-weight father was not associated with an increased risk of obesity in childhood. [76] This discrepancy suggests a role for epigenetic factors in hereditary risk.

Genetic susceptibility loci

Rarely, obesity may be caused by a single gene, but much more commonly it is a complex interplay of susceptibility loci and environmental factors. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found a robust number of genetic susceptibility loci associated with obesity. A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the FTO (fat mass and obesity associated) gene and SNPs near the MC4R (melanocortin 4 receptor) gene have been highly associated with BMI. [77, 78, 79, 80]

Although many genetic susceptibility loci have been discovered, the effect sizes of the established loci are small, and combined they explain only a fraction of the variation in BMI between individuals. Their low predictive value means that they have limited value in clinical medicine. [81] Moreover, the fact that increases in the rate of obesity over the last decades have coincided with changes in dietary habits and activity suggests an important role for environmental factors.

Monogenic models for obesity in humans and experimental animals

More than 90% of human cases of obesity are thought to be multifactorial. Nevertheless, the recognition of monogenic variants has greatly enhanced knowledge of the etiopathogenesis of obesity. [82] As previously mentioned, Friedman and colleagues discovered leptin in 1994 and ushered in an explosion of research and a great increase in knowledge about regulation of the human feeding and satiation cycle.

POMC and MC4R

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is converted into alpha–melanocyte-stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH), which acts centrally on melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R) to reduce dietary intake. [83] Genetic defects in POMC production and mutations in the MC4R gene are described as monogenic causes of obesity in humans. [84]

Of particular interest is the fact that patients with POMC gene mutations tend to have red hair because of the resultant deficiency in MSH production. Also, because of their diminished levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), they tend to have central adrenal insufficiency.

Data suggest that up to 5% of children with severe obesity have MC4R or POMC mutations. [85] If confirmed, these would be among the most common identifiable genetic defects associated with obesity in humans (band 2p23 for POMC and band 18q21.3 for MC4R).

Leptin deficiency

Rare cases of humans with congenital leptin deficiency caused by mutations in the leptin gene have been identified. (The involved band is at 7q31.) The disorder is autosomal recessive and manifested by severe obesity and hyperphagia accompanied by metabolic, neuroendocrine, and immune dysfunction. [86] It is exquisitely sensitive to leptin injection, with reduced dietary intake and profound weight loss.

Convertase mutation

The prohormone convertase, an enzyme that is critical in protein processing, appears to be involved in the conversion of POMC to alpha-MSH. Rare patients with alterations in this enzyme have had clinically significant obesity, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and central adrenal insufficiency. This is one of the few models of obesity not associated with insulin resistance.

PPAR-gamma

PPAR-gamma is a transcription factor that is involved in adipocyte differentiation. All humans with mutations of the receptor (at band 3p25) described so far have had severe obesity.

Inflammatory factors

Evolving data suggest that a notable inflammatory, and possibly infective, etiology may exist for obesity. Adipose tissue is known to be a repository of various cytokines, especially interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha. One study showed an association between obesity and a high-normal level of plasma procalcitonin, a dependent variable that reflects a state of distress or inflammation. [87]

Data have shown that adenovirus-36 infection is associated with obesity in chickens and mice. In human studies, the prevalence of adenovirus-36 infection is 20-30% in people with obesity, versus 5% in people without obesity. Despite these provocative findings, the roles of infection and inflammation in the pathogenesis of obesity remain unclear.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

More than 100 million US adults aged 20 years or older have obesity, including over 22 million with severe obesity. [88] Among young people in the United States aged 2-19 years, about 14.7 million have obesity. [89] A report from the National Center for Health Statistics stated that in US individuals aged 20 years or older, the prevalence of obesity rose steadily from 19.4% in 1997 to 31.4% for the period January-September 2017. [90, 91]

According to NHANES, between 2017 and March 2020, the U.S. obesity rate in children and adolescents aged 2-19 years was 19.7%. The age-adjusted prevalence for adults aged 20 years and older during this period was 41.9%, with the age-adjusted prevalence of severe obesity in this group being 9.2%. [2]

Another study by Ward et al estimated that among US adults in 2016, excess weight led to more than 1300 deaths per day. For women, the relative excess mortality rate associated with elevated weight came to 21.9%, versus 13.9% for men; the rate was also particularly high for the non-Hispanic Black adult population, being 22.8%, versus 17.0% for the non-Hispanic White adult population. [92]

International statistics

The prevalence of obesity worldwide is increasing, particularly in the industrialized nations of the Northern hemisphere, such as the United States, Canada, and most countries of Europe. According to the WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022, in the WHO European Region (consisting of more than 50 countries), there are “one in three school-aged children, one in four adolescents and almost 60% of the adult population now living with overweight or obesity.” [93, 94]

Moreover, reports from countries such as Malaysia, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and China have detailed an epidemic of obesity in recent decades. Data from the Middle Eastern countries of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, and Lebanon, among others, indicate this same disturbing trend, with levels of obesity often exceeding 40%.

Internationally, rates of obesity are higher in women than in men. A somewhat higher rate would be expected, given the biologically higher percentage of body fat in women.

Information from the Caribbean and from South America highlights similar trends. Although data from Africa are scant, a clear and distinct secular trend of profoundly increased BMIs is observed when people from Africa emigrate to the northwestern regions of the world. Comparisons of these indices among Nigerians and Ghanaians residing in their native countries with indices in recent immigrants to the United States show this trend poignantly.

A report from the World Obesity Federation predicted that by 2035, over 4 billion people (51% of the world’s population) will have overweight or obesity. The report indicated that obesity rates are particularly increasing in children and in lower income countries, with the number of children with obesity possibly more than doubling between 2020 and 2035. It was further estimated that morbidities associated with being overweight would cost, globally, more than $4 trillion per year by 2035. [95]

Although socioeconomic class and the prevalence of obesity are negatively correlated in most industrialized countries, including the United States, this correlation is distinctly reversed in many relatively undeveloped areas, including China, Malaysia, parts of South America, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Race-related demographics

Obesity is a cosmopolitan disease that affects all races worldwide. However, certain ethnic and racial groups appear to be particularly predisposed. The Pima Indians of Arizona and other ethnic groups native to North America have a particularly high prevalence of obesity. In addition, Pacific islanders (eg, Polynesians, Micronesians, Maoris), African Americans, and Hispanic populations (either Mexican or Puerto Rican in origin) in North America also have particularly high predispositions to the development of obesity.

Secular trends clearly emphasize the importance of environmental factors (particularly dietary issues) in the development of obesity. In many genetically similar cohorts of high-risk ethnic and racial groups, the prevalence of obesity in their countries of origin is low but rises considerably when members of these groups emigrate to the affluent countries of the Northern Hemisphere, where they alter their dietary habits and activities. These findings form the core concept of the thrifty gene hypothesis espoused by Neel and colleagues. [96]

The thrifty gene hypothesis posits that human evolution favored individuals who were more efficient at storing energy during times of food shortage and that this historic evolutionary advantage is now a disadvantage during a time of abundant food availability.

Age-related demographics

Children, particularly adolescents, with obesity have a high probability of becoming adults with obesity; hence, the bimodal distribution of obesity portends a large-scale obesity epidemic in the coming decades. Taller children generally tend to be more obese than shorter peers, are more insulin-resistant, and have increased leptin levels. [97]

Adolescent obesity poses a serious risk for severe obesity during early adulthood, particularly in non-Hispanic Black women. This calls for a stronger emphasis on weight reduction during early adolescence, specifically targeting groups at greater risk. [98]

Prognosis

Data from insurance databases and large, prospective cohorts, such as findings from the Framingham and NHANES studies, clearly indicate that obesity is associated with a substantial increase in morbidity and mortality rates.

The adverse consequences of obesity may be attributed in part to comorbidities, but results from several observational studies detailed by the Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight Adults, as well as results from reports by Allison, Bray, and others, exhaustively show that obesity on its own is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and greater all-cause mortality. [99, 100, 101]

For a person with a BMI of 25-28.9 kg/m2, the relative risk for coronary heart disease is 1.72. The risk progressively increases with an increasing BMI; with BMIs of greater than 33 kg/m2, the relative risk is 3.44. Similar trends have been demonstrated in the relationship between obesity and stroke or chronic heart failure.

Overall, obesity is estimated to increase the cardiovascular mortality rate 4-fold and the cancer-related mortality rate 2-fold. [8, 9, 10] As a group, people with severe obesity have a 6- to 12-fold increase in the all-cause mortality rate. Although the exact magnitude of the attributable excess in mortality associated with obesity (about 112,000-365,000 excess deaths annually) has been disputed, obesity is indisputably the greatest preventable health-related cause of mortality after cigarette smoking. [99]

For persons with severe obesity (BMI ≥40), life expectancy is reduced by as much as 20 years in men and by about 5 years in women. The greater reduction in life expectancy for men is consistent with the higher prevalence of android (ie, predominantly abdominal) obesity and the biologically higher percentage of body fat in women. The risk of premature mortality is even greater in persons with obesity who smoke.

Some evidence suggests that, if unchecked, trends in obesity in the United States may be associated with overall reduced longevity of the population in the near future. Data also show that obesity is associated with an increased risk and duration of lifetime disability. Furthermore, obesity in middle age is associated with poor indices of quality of life in old age.

The mortality data appear to have a U- or J-shaped conformation in relation to weight distribution. [102] Underweight was associated with substantially high risk of death in a study of Asian populations, and a high BMI is also associated with an increased risk of death, except in Indians and Bangladeshis. [103] A study in Whites found that a BMI of 20-24.9 was associated with the generally lowest all-cause mortality and reinforced that overweight and underweight lead to an increased risk of death. [104]

The degree of obesity (generally indicated by the BMI) at which mortality discernibly increases in African Americans and Hispanic Americans is greater than in White Americans; this observation suggests a notable racial spectrum and difference in this effect. The optimal BMI in terms of life expectancy is about 23-25 for Whites and 23-30 for Blacks. Emerging data suggest that the ideal BMI for Asians is substantially lower than that for Whites. [105]

On the other hand, Boggs et al found that among Black women, the risk of death from any cause rose with a BMI of 25 or higher, a pattern similar to that seen in Whites. [106]

Stated another way, individuals who have abdominal obesity (elevated waist circumference) have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Most individuals with a BMI of over 25 and essentially all persons with a BMI of more than 30 have abdominal obesity.

In Whites and in African American people, abdominal obesity is defined as a waist circumference of 88 cm or higher and of 102 cm or higher, for women and men, respectively. In south and southeast Asian people, abdominal obesity is defined as a waist circumference of at least 80 cm in women and at least 85 cm in men.

Factors that modulate the morbidity and mortality associated with obesity include the following:

-

Age of onset and duration of obesity

-

Severity of obesity

-

Amount of central adiposity

-

Comorbidities

-

Gender

-

Level of cardiorespiratory fitness

-

Race

A study by Jung et al found a correlation between abdominal obesity and high-volume benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), ie, a prostate volume of 40 mL or greater. The report, which involved 571 participants, also found a positive association between serum leptin levels and high-volume BPH and a negative association between serum adiponectin and high-volume BPH. [107]

Morbidity in elderly persons

A longitudinal study by Stessman et al of more than 1000 individuals indicated that a normal BMI, rather than obesity, is associated with a higher mortality rate in elderly people. [108] The investigators determined that a unit increase in BMI in female members of the cohort could be linked to hazard ratios (HRs) of 0.94 at age 70 years, 0.95 at age 78 years, and 0.91 at age 85 years.

In men, a unit increase in BMI was associated with HRs of 0.99 at age 70 years, 0.94 at age 78 years, and 0.91 at age 85 years. According to a time-dependent analysis of 450 cohort members followed from age 70 to age 88 years, a unit increase in BMI produced an HR of 0.93 in women and in men. [108]

Similar results were found in a Japanese study of 26,747 older persons (aged 65-79 years at baseline). Tamakoshi et al reported no elevation in all-cause mortality risk in men with overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) or obesity (BMI ≥30.0); slightly elevated hazard ratios were found in women in the group with obesity, but not in the group with overweight, compared with women in the mid–normal-range group. In contrast, an association was found between a low BMI and an increased risk of all-cause mortality, even among persons in the lower-normal BMI range. [109]

Weight-loss programs

Most individuals are able to attain weight loss in the short term, but weight regain is unfortunately a common pattern. On average, participants in nonsurgical weight-management programs lose approximately 10% of their initial body weight over 12-24 weeks, but the majority regain two thirds of the weight lost within a year.

Old data indicated that 90-95% of the weight lost is regained in 5 years. Subsequent data showed that more intensive and structured nonsurgical weight management may help a significant number of patients to maintain most of the weight lost for up to 4 years.

In the Look AHEAD study, 887 of 2570 participants (34.5%) in the intensive lifestyle group lost at least 10% of their weight at year 1. Of these, 374 (42.2%) maintained this loss at year 4, and another 17% maintained 7-10% weight loss at 4 years. More than 45% of all intensive lifestyle participants had achieved and maintained a clinically significant weight loss (≥ 5%) at 4 years. [110]

Patient Education

In studies among low-income families, adults and adolescents noted caloric information when reading labels. [111] However, this information did not affect food selection by adolescents or parental food selections for children.

NHANES found that patients who received a formal diagnosis of overweight/obesity from a healthcare provider demonstrated a higher rate of dietary change and/or physical activity than did persons with overweight/obesity in whom these conditions remained undiagnosed. These findings are important for any clinician caring for patients with overweight/obesity. [112]

A meta-analysis by Waters et al of 55 studies assessing educational, behavioral, and health promotion interventions in children aged 0-18 years found that these interventions reduced BMI (standardized mean difference in adiposity, 0.15 kg/m2). [113] The study concluded that child obesity prevention programs have beneficial effects.

-

Central nervous system neurocircuitry for satiety and feeding cycles.

-

Comorbidities of obesity.

-

Energy balance equation.

-

Secondary causes of obesity.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Patient Screening, Assessment, and Expectations

- Weight-Loss Goals

- Weight-Loss Maintenance

- Treatment of Childhood Obesity

- Energy Expenditure and Weight Loss

- Conventional Diets

- Water Drinking

- Exercise Programs

- Behavioral Changes

- Antiobesity Medications

- Fat Substitutes

- Bariatric Surgery

- Inpatient Care

- Deterrence and Prevention

- Consultations

- Long-Term Monitoring

- Show All

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Media Gallery

- References