Background

Amebiasis is an infection primarily caused by the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica. [1] It is mainly transmitted through the fecal-oral route, but also can be spread sexually via oral-anal contact. While many individuals infected with this parasite do not show symptoms, those who do may experience a range of issues from mild diarrhea to severe dysentery. In certain cases, the infection can result in extraintestinal complications, including liver abscesses and, in rare instances, brain abscesses.

Diagnosis involves identifying E histolytica in stool samples, which can be confirmed through immunoassays that detect specific antigens or through serological tests if extraintestinal disease is suspected. For symptomatic patients, treatment generally includes oral medications such as tinidazole, metronidazole, secnidazole, or ornidazole, followed by paromomycin or another drug that targets cysts in the colon. This protozoan is found globally, and another species, Entamoeba dispar, has also been noted as a potential cause of amebic liver abscesses. The highest rates of amebiasis are observed in developing countries, where inadequate sanitation and insufficient barriers between human feces and food and water supplies contribute to its spread.

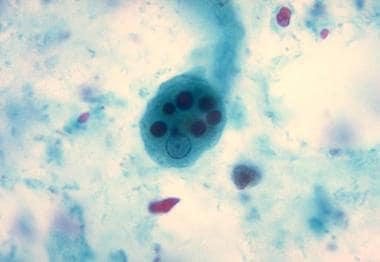

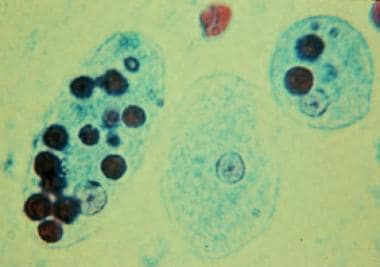

Trichrome stain of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in amebiasis. Two diagnostic characteristics are observed. Two trophozoites have ingested erythrocytes, and all 3 have nuclei with small, centrally located karyosomes.

Trichrome stain of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in amebiasis. Two diagnostic characteristics are observed. Two trophozoites have ingested erythrocytes, and all 3 have nuclei with small, centrally located karyosomes.

Although most cases of amebiasis are asymptomatic, dysentery and invasive extraintestinal disease can occur. Chronic non-dysenteric colitis is the most frequent form of amebiasis in people of all ages. [2] Amebic liver abscess is the most common manifestation of invasive amebiasis, but other organs can also be involved, including pleuropulmonary, cardiac, cerebral, renal, genitourinary, peritoneal, and cutaneous sites. In developed countries, amebiasis primarily affects migrants from and travelers to endemic regions, men who have sex with men, and immunosuppressed or institutionalized individuals.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has classified E histolytica as a category B biodefense pathogen because of its low infectious dose, environmental stability, resistance to chlorine, and ease of dissemination through contamination of food and water supplies. [3]

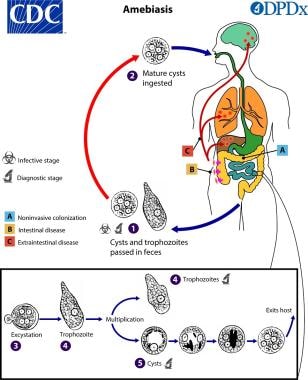

E histolytica is transmitted via ingestion of the cystic form (infective stage) of the protozoa. Viable in the environment for weeks to months, cysts can be found in fecally contaminated soil, fertilizer, or water or on the contaminated hands of food handlers. Fecal-oral transmission can also occur in the setting of anal sexual practices or direct rectal inoculation through colonic irrigation devices.

Excystation then occurs in the terminal ileum or colon, resulting in trophozoites (invasive form). The trophozoites can penetrate and invade the colonic mucosal barrier, leading to tissue destruction, secretory bloody diarrhea, and colitis resembling inflammatory bowel disease. In addition, the trophozoites can spread hematogenously via the portal circulation to the liver or even to more distant organs (see Pathophysiology).

Life cycle of amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica). Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Life cycle of amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica). Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

E histolytica is capable of causing a spectrum of illnesses (see Presentation). Intestinal conditions resulting from E histolytica infection include the following:

-

Asymptomatic infection

-

Symptomatic noninvasive infection

-

Acute proctocolitis (dysentery)

-

Fulminant colitis with perforation

-

Toxic megacolon

-

Chronic nondysenteric colitis

-

Ameboma

-

Perianal ulceration

-

Rectovaginal fistulae

Extraintestinal conditions resulting from E histolytica infection include the following:

-

Liver abscess

-

Pleuropulmonary disease

-

Peritonitis

-

Pericarditis

-

Brain abscess

-

Genitourinary disease

Laboratory diagnosis of amebiasis is made by demonstrating the organism or by employing immunologic techniques. In addition to standard blood tests, other laboratory studies employed for diagnosis include microscopy, culture, serologic testing, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (see Workup).

Treatment of amebiasis includes pharmacologic therapy, surgical intervention, and preventive measures, as appropriate (see Treatment). Most individuals with amebiasis may be treated on an outpatient basis, though several clinical scenarios may favor inpatient care.

See Common Intestinal Parasites, a Critical Images slideshow, to help make an accurate diagnosis.

Pathophysiology

E histolytica is a pseudopod-forming, nonflagellated protozoal parasite that causes proteolysis and tissue lysis (hence the species name) and can induce host-cell apoptosis. Humans and perhaps nonhuman primates are the only natural hosts.

Ingestion of E histolytica cysts (see the first image below) from the environment is followed by excystation in the terminal ileum or colon to form highly motile trophozoites (see the second image below). Upon colonization of the colonic mucosa, the trophozoite may encyst and is then excreted in the feces, or it may invade the intestinal mucosal barrier and gain access to the bloodstream, whereby it is disseminated to the liver, lung, and other sites. Excreted cysts reach the environment to complete the cycle.

Disease may be caused by only a small number of cysts, but the processes of encystation and excystation are poorly understood.

Adherence and Immune Response

The adherence of trophozoites to colonic epithelial cells seems to be mediated by a galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine (GAL/GalNAc)–specific lectin, [4, 5, 6] a 260-kd surface protein containing a 170-kd subunit and a 35-kd subunit. A mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA) response against this lectin can result in fewer recurrent infections. [7]

Cytolytic Mechanisms

Both lytic and apoptotic pathways have been described. Cytolysis can be undertaken by amebapores, a family of peptides capable of forming pores in lipid bilayers. [4] Furthermore, in animal models of liver abscess, trophozoites induced apoptosis via a non-Fas and non–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α1 receptor pathway. [8] The amebapores, at sublytic concentrations, also can induce apoptosis.

Role of Cysteine Proteinases

Cysteine proteinases have been directly implicated in invasion and inflammation of the gut and may amplify interleukin (IL)-1–mediated inflammation by mimicking the action of human IL-1–converting enzyme, cleaving IL-1 precursor to its active form. [4, 9] The cysteine proteinases can also cleave and inactivate the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a, as well as IgA and immunoglobulin G (IgG). [10, 11]

Transmembrane Kinases and Virulence

E histolytica possesses about 100 putative transmembrane kinases (TMKs), which are commonly divided into 9 subgroups. Of these, EhTMKB1-9 is expressed in proliferating trophozoites and induced by serum. In an animal model, it was found to be involved in phagocytosis and to play a role as a virulence factor in amebic colitis. [12] These findings suggest that TMKs such as EhTMKB1-9 may be attractive targets for future drug development.

Inflammatory Mediators and Immune Response

Epithelial cells also produce various inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-8, and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, leading to the attraction of neutrophils and macrophages. [13, 14] Corticosteroid therapy is known to worsen the clinical outcome, possibly because of its blunting effect on this innate immune response.

Host Defense Mechanisms

Additional host defenses, including the complement system, could be inhibited directly by the trophozoites, as is suggested by the finding that a region of the GAL/GalNAc–specific lectin showed antigenic crossreactivity with CD59, a membrane inhibitor of the C5b-9 attack complex in human red blood cells. [15]

Spread of Amebiasis to the Liver

Spread of amebiasis to the liver occurs via the portal blood. The pathogenic strains evade the complement-mediated lysis in the bloodstream. Trophozoites that reach the liver create unique abscesses with well-circumscribed regions of dead hepatocytes surrounded by few inflammatory cells and trophozoites and unaffected hepatocytes. These findings suggest that E histolytica organisms are able to kill hepatocytes without direct contact. [4]

Immune Responses in Amebic Liver Abscess

Serum antibodies in patients with amebic liver abscess develop in 7 days and persist for as long as 10 years. A mucosal IgA response to E histolytica occurs during invasive amebiasis; however, no evidence suggests that invasive amebiasis is increased in incidence or severity in patients with IgA deficiency.

Cell-Mediated Immunity

Cell-mediated immunity is important in limiting the disease and preventing recurrences. Antigen-specific blastogenic responses occur, leading to production of lymphokines, including interferon-delta, which activates the killing of E histolytica trophozoites by the macrophages. This killing depends on contact, oxidative pathways, nonoxidative pathways, and nitric oxide (NO). Lymphokines, such as TNF-α, are capable of activating the amebicidal activity of neutrophils. Incubation of CD8+ lymphocytes with E histolytica antigens in vitro elicits cytotoxic T-cell activity against the trophozoites. During acute invasive amebiasis, T-cell response to E histolytica antigens is depressed by a parasite-induced serum factor.

Etiology

Amebiasis is a parasitic infection caused by the protozoal organism E histolytica, which can give rise both to intestinal disease (eg, colitis) and to various extraintestinal manifestations, including liver abscess (most common) and pleuropulmonary, cardiac, and cerebral dissemination.

The genus Entamoeba contains many species, some of which (ie, E histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, Entamoeba moshkovskii, Entamoeba bangladeshi, Entamoeba polecki, Entamoeba coli, and Entamoeba hartmanni) can reside in the human interstitial lumen. Of these, E histolytica is the only one definitely associated with disease, although a 2012 report suggested E moshkovskii to be the causative agent of diarrhea in infants. [16, 17] Although E dispar and E histolytica cannot be differentiated by means of direct examination, molecular techniques have demonstrated that they are indeed two different species, with E dispar being commensal (as in patients with HIV infection) and E histolytica pathogenic. [16]

It is currently believed that many individuals with Entamoeba infections are actually colonized with E dispar, which appears to be 10 times more common than E histolytica [16] ; however, in certain regions (eg, Brazil and Egypt), asymptomatic E dispar and E histolytica infections are equally prevalent. [4] In Western countries, approximately 20-30% of men who have sex with men are colonized with E dispar. [16]

E histolytica is transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route. Infective cysts can be found in fecally contaminated food and water supplies and contaminated hands of food handlers. Sexual transmission is possible, especially in the setting of oral-anal practices (anilingus). [18] Poor nutrition, through its effect on immunity, has been found to be a risk factor for amebiasis. [19]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The overall prevalence of amebiasis in the United States is approximately 4%. E dispar infection, which always is asymptomatic, is 10 times more common than E histolytica infection. Moreover, only 10% of E histolytica infections cause invasive disease. Therefore, only 1% of persons with stool microscopy findings that reveal Entamoeba develop symptomatic amebiasis.

In the United States, amebiasis is most frequently observed in the following [20] :

-

Individuals who have traveled to tropical regions with inadequate sanitation

-

Immigrants from tropical countries where sanitation is lacking

-

Residents of facilities with substandard sanitary conditions

-

Individuals who engage in anal sex

An increased prevalence of amebiasis is noted in institutionalized persons (especially those with intellectual disabilities), male homosexuals, and persons living in communal settings.

Travelers to endemic areas are at risk for infection and represent most US cases. It is estimated that 14 of every 1,000 returning travelers with diarrhea have amebiasis, which accounts for 12.5% of all microbiologically confirmed cases. [21] Travel to South Asia, the Middle East, and South America poses the highest risk. Amebic liver abscess has been reported after a median duration of 3 months but may occur years later.

The US national death certificate data from 1990 to 2007 identified 134 deaths from amebiasis. A declining trend of deaths has been noted, with a current rate of 5 deaths per year. [22] More than 40% of reported deaths occurred in residents of California and Texas, with US-born persons accounting for most amebiasis deaths. [23]

International statistics

The parasite E histolytica is found worldwide, but the majority of infections occur in Central America, western South America, western and southern Africa, India, and specific regions of South Asia. In countries with safe food and water supplies, most cases are reported among recent immigrants and travelers returning from endemic areas.

It is estimated that approximately 50 million individuals globally develop amebic colitis or extraintestinal disease each year, resulting in as many as 73,000 fatalities attributed to the infection. [1]

Previous estimates of E histolytica infections, which relied on stool examinations for ova and parasites, have proven inaccurate, as these tests cannot distinguish E histolytica from E dispar and E moshkovskii. In developing countries, the prevalence of E histolytica, as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of stool samples from asymptomatic individuals, ranges from 1% to 21%. Estimates suggest that around 500 million people with Entamoeba infections are colonized by E dispar. [16]

The prevalence of Entamoeba infection can reach as high as 50% in certain regions of Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. [24] Seroprevalence studies in Mexico have shown that over 8% of the population tested positive for E histolytica. [25] In endemic areas, up to 25% of patients may carry antibodies to E histolytica due to prior infections, which are often asymptomatic. The prevalence of asymptomatic E histolytica infections appears to vary by region; for instance, in Brazil, it may be as high as 11%.

In Egypt, 38% of individuals presenting with acute diarrhea at outpatient clinics were diagnosed with amebic colitis. [4] A study in Bangladesh found that preschool children experienced an average of 0.09 episodes of E histolytica-associated diarrhea and 0.03 episodes of amebic dysentery each year. In Hue City, Vietnam, the annual incidence of amebic liver abscess was reported to be 21 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. [26]

An epidemiological study conducted in Mexico City indicated that 9% of the population was infected with E histolytica in the 5 to 10 years prior to the study. Contributing factors to fecal-oral transmission included poor education, poverty, overcrowding, contaminated water supplies, and unsanitary conditions.

Several studies have explored the association between amebiasis and AIDS. [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] The impact of the AIDS pandemic on the prevalence of invasive amebiasis remains a topic of debate. While some reports suggest that invasive amebiasis does not increase among patients with HIV infection, [33] others indicate that amebic liver abscess is becoming a significant parasitic infection in individuals with HIV in both disease-endemic and non-endemic areas. [34]

Among 31 patients with amebic liver abscess at Seoul National University Hospital from 1990 to 2005, 10 (32%) were found to be HIV-positive. [35] Additionally, a case-control study of individuals seeking voluntary counseling and testing for HIV infection identified several risk factors for amebiasis, including homosexual activity, fecal-oral contamination, lower educational achievement, and older age. [36]

Age-related demographics

Symptomatic intestinal amebiasis occurs in all age groups. Liver abscesses due to amebiasis are 10 times more frequent in adults than in children. Very young children seem to be predisposed to fulminant colitis. [37]

Sex-related demographics

Amebic colitis affects both sexes equally. [4] However, invasive amebiasis is much more common in adult males than in females. In particular, amebic liver abscess is 7-12 times more common in men than in women, with a predominance among men aged 18-50 years. The reason for this disparity is unknown, though hormonal effects may be implicated, as the prevalence of amebic liver abscess also is increased among postmenopausal women. Alcohol also may be an important risk factor. [38]

Among prepubertal children, amebic liver abscess is equally common in both sexes. [4] Acuna-Soto et al noted that asymptomatic E histolytica infection is distributed equally between sexes. [39] Therefore, the higher proportion of adult males with invasive amebiasis may be due to a male susceptibility to invasive disease.

Race-related demographics

In Japan and Taiwan, HIV seropositivity is a risk factor for invasive extraintestinal amebiasis. [34] This association has not been observed elsewhere. Among HIV-positive patients, homosexual intercourse, and not immunosuppressed status, seems to be a risk factor for amebic colitis. [40]

Prognosis

Amebic infections can lead to significant morbidity while causing variable mortality. In terms of protozoan-associated mortality, amebiasis is second only to malaria. The severity of amebiasis is increased in the following groups:

-

Children, especially neonates

-

Pregnant and postpartum women

-

Those using corticosteroids

-

Those with malignancies

-

Malnourished individuals

Intestinal infections due to amebiasis generally respond well to appropriate therapy, though it should be kept in mind that previous infection and treatment will not protect against future colonization or recurrent invasive amebiasis.

Asymptomatic intestinal amebiasis occurs in 90% of infected individuals. However, only 4%-10% of individuals with asymptomatic amebiasis who were monitored for 1 year eventually developed colitis or extraintestinal disease. [16]

With the introduction of effective medical treatment, mortality has fallen below 1% for patients with uncomplicated amebic liver abscess. However, amebic liver abscess can be complicated by sudden intraperitoneal rupture in 2-7% of patients, and this complication leads to a higher mortality. [4]

Case-fatality rates associated with amebic colitis range from 1.9% to 9.1%. Amebic colitis evolves to fulminant necrotizing colitis or rupture in approximately 0.5% of cases; in such cases, mortality may exceeds 40% [41] or even, according to some reports, 50%.

Pleuropulmonary amebiasis has a 15%-20% mortality rate. Amebic pericarditis has a case-fatality rate of 40%. Cerebral amebiasis carries a very high mortality (90%).

A study of 134 deaths in the United States from 1990 to 2007 found that mortality was highest in men, Hispanics, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and people aged 75 years or older. [23] An association with HIV infection was also observed. Although deaths declined during the course of the study, more than 40% occurred in California and Texas. US-born persons accounted for the majority of amebiasis deaths; however, all of the fatalities in Asian/Pacific Islanders and 60% of the deaths in Hispanics were in foreign-born individuals.

Patient Education

Individuals traveling to endemic areas should be advised on practices that minimize the risk of amebiasis, such as the following [20, 1] :

-

Avoid drinking contaminated water; use bottled water while traveling if possible

-

If local water is to be drunk, purify it by (a) boiling it for more than 1 minute, (b) using 0.22 µm filtration, or (c) iodinating it with tetraglycine hydroperiodide

-

Avoid eating raw fruits and salads, which are difficult to sterilize; eat only cooked food or self-peeled fruits if possible

-

Wash uncooked vegetables and soak them in acetic acid or vinegar for 10-15 minutes

-

Trichrome stain of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in amebiasis. Two diagnostic characteristics are observed. Two trophozoites have ingested erythrocytes, and all 3 have nuclei with small, centrally located karyosomes.

-

Trichrome stain of Entamoeba histolytica cyst in amebiasis. Each cyst has 4 nuclei with characteristically centrally located karyosomes. Cysts measure 12-15 mm.

-

Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Entamoeba histolytica cyst. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Gross pathology of intestinal ulcers due to amebiasis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Histopathology of typical flask-shaped ulcer of intestinal amebiasis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Entamoeba histolytica in liver aspirate, trichrome stain. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Histopathology of amebiasis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Life cycle of amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica). Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).