Practice Essentials

Meningococcemia is a bloodstream infection (BSI) caused by Neisseria meningitidis. Its wide variety of acute presentations result from its ability to produce diffuse endovascular damage.

Chronic meningococcemia is an infrequent presentation with skin and joint findings, without any meningeal involvement. [1]

The most commonly affected age groups are 6 months-5 years and 15-24 years.

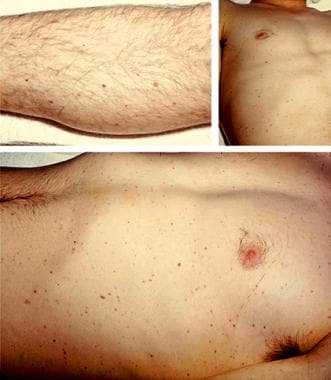

A 9-month-old baby in septic shock with purpuric Neisseria meningitis skin lesions. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

A 9-month-old baby in septic shock with purpuric Neisseria meningitis skin lesions. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with acute meningococcemia may present with meningitis, meningitis with meningococcemia, or meningococcemia without apparent meningitis.

The clinical presentation of meningococcemia may include any of the following [1] :

-

A nonspecific prodrome of cough, headache, and sore throat

-

The above, followed by a few days of upper respiratory symptoms, increasing temperature, and chills

-

Subsequent malaise, weakness, myalgias, headache, nausea, vomiting, and arthralgias

-

The characteristic petechial skin rash usually is located on the trunk and legs and rapidly may evolve into purpura.

In fulminant meningococcemia, a hemorrhagic eruption, hypotension, cardiac depression, and rapid enlargement of petechiae and purpuric lesions may be seen.

Serogroup W disease may be associated with atypical presentations, including septic arthritis, pneumonia, endocarditis, and epiglottitis.

The meningitis of meningococcemia is associated with the following [1, 2] :

-

Headache

-

Fever

-

Vomiting

-

Photophobia

-

Lethargy

-

Neck stiffness

-

Rash (more than 50% of cases)

-

Seizures (20% of patients at presentation and an additional 10% of patients within 72 hours)

-

Early nonspecific symptoms

Meningococcemia is characterized by the following [1] :

-

Fever

-

Initial rash that may be erythematous or maculopapular and is short-lived, followed by petechiae and purpura

-

Vomiting

-

Headache

-

Myalgias that may be quite severe

-

Sore throat

-

Abdominal pain

-

Tachycardia/tachypnea

-

Hypotension

-

Cool extremities

-

An initially normal level of consciousness

-

Early symptoms are similar to those of viral illness such as influenza or streptococcal pharyngitis; however, this infection accelerates at a rate matched by few other infections

-

Mild cases may be associated with transient BSI and limited skin lesions. These may become more aggressive but usually resolve

-

The presentation may be that of urethritis when the pathogen is transmitted during sex.

The physical findings may include the following [1] :

-

Dermatologic manifestations: Petechiae, rash, ecchymoses, purpura

-

Meningococcal meningitis: Pain and resistance to neck flexion, other signs of meningeal irritation, petechiae, fever (of variable intensity)

-

Fulminant meningococcemia: Purpuric eruption, hemorrhages on buccal mucosa and conjunctivae, cyanosis, hypotension, profound shock, high fever, pulmonary insufficiency, no signs of meningitis

-

Meningococcal septicemia: Fever, rash, tachycardia, hypotension, cool extremities, initially normal level of consciousness

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The laboratory findings in the early stages of meningococcal disease often are nonspecific. A definitive diagnosis requires retrieval of meningococci from blood, cerebrospinal fluid, joint fluid, or skin lesions. Studies may include the following [1] :

-

Complete blood count

-

Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine

-

Fibrinogen and C-reactive protein

-

Coagulation studies

-

Electrolytes

-

Tests for end-organ damage

-

Blood and throat cultures

-

Imaging studies: chest radiography, echocardiography, CT scan

-

Needle aspiration and skin biopsy

-

Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis

-

Serogrouping/serotyping

-

Singleplex real-time PCR assays

-

Multiplex real-time PCR assays [3]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Clinical guideline summaries related to meningococcal disease include the following:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [4]

Patients with a rash consistent with meningococcemia should be started on parenteral antibiotics within 1 hour of presentation. [5]

Conditions associated with poor outcomes include the following [1] :

-

Shock

-

Absence of meningitis

-

Rapidly extending rash

-

Low WBC count

-

Coagulopathy

-

Deteriorating level of consciousness

-

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

-

Immunodeficiencies

Antibiotics recommended for the treatment of meningococcemia include the following [6] :

-

Third-generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone (2 g IV q24h) or cefotaxime (2 g IV q4-6h) are the preferred antibiotics

-

Alternative agents include (1) ampicillin 12 g/d either by continuous infusion or by divided dosing q4h or Penicillin G 18-24 million units IV continuously or by divided dose q 4 hr. These beta-lactams only should be started if the isolate is found to be susceptible

-

Moxifloxacin 400mg /day IV

-

The course of therapy is generally 7-10 days

-

Chloramphenicol may be considered in patients who are allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics. There have been reports of increasing worldwide

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

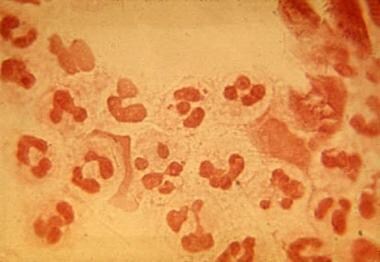

N meningitidis is an encapsulated gram-negative diplococcus. There are at least 12 serogroups of the bacterium based on capsular polysaccharide antigenic differences. Serogroups A, B, C, Y, and W-135 cause 90% of human disease.

See Pathophysiology, Etiology, and Workup for more detail.

Humans are the only reservoir of N meningitidis, which is transiently part of the oropharyngeal flora of up to 10% of the population. These individuals remain asymptomatic. N meningitidis is transmitted by respiratory secretions or by close contact, which facilitates the exchange of secretions. The incubation period ranges from 2-10 days. Epidemics most commonly are due to A, B, or C serotypes.

Risk groups include the following [4, 7] :

Specific categories of individuals at high risk for meningococcal disease include the following [8] :

-

Laboratory workers

-

Patients with HIV

-

Military recruits

-

Outbreaks with type B among college freshmen living in dormitories

-

Travelers to endemic zones (sub-Saharan Africa)

-

Deficiencies of terminal complement including vaccinated patients on eculizumab

-

Men who have sex with men (MSM) can develop urethritis due to an anaerobic tolerant clade of N meningitidis that facilitates rectal/urethral transmission. In this population, Gram negative diplococci should not be assumed to represent N gonorrhea.

-

Individuals with asplenia

Thirty percent to 50% of cases of acute meningococcemia present with meningitis alone, 40% with meningitis and BSI, and 7-10% with BSI alone. [9]

See Presentation and Workup for more detail.

N meningitides remains a major infectious cause of childhood death in developed countries. The mortality rate remains around 5-10%. There has been little improvement in morbidity and mortality since the beginning of the antibiotic era because of the inability of antimicrobials to prevent the cardiovascular collapse brought about by the organism’s endotoxin. [10]

Carriers

Approximately 2% of children younger than 2 years, 5% of children up to 17 years, and 20-40% of young adults are carriers of N meningitidis. Overcrowded conditions (eg, schools, military camps) can significantly increase the carrier rate.

Screening of military recruits performed during recent epidemics demonstrated that, although as many as 95% of recruits were oropharyngeal carriers, only 1% developed systemic disease. Because very few of those infected had ever been in contact with another patient with a similar history, asymptomatic carriage is thought to be the major source of transmission of pathogenic strains.

Immunity to N meningitidis appears to be acquired through the intermittent nasal carriage of meningococci and by antigenic cross-reaction with enteric flora during the first 2 decades of life.

See Pathophysiology, Etiology, and Epidemiology for more details.

Pathophysiology

Meningococcemia results in widespread vascular injury characterized by endothelial necrosis, intraluminal thrombosis, and perivascular hemorrhage. Endotoxin, cytokines, and free radicals damage the vascular endothelium, producing platelet deposition and vasculitis. Cytokines play a major role in its pathogenesis by causing severe hypotension, reduced cardiac output, and increased endothelial permeability. [11]

The clinical picture of meningococcemia is the product of compartmental intravascular infection and intracranial bacterial growth and inflammation. The pathogen binds tightly to the endothelial cells by type IV pili. From this arises microcolonies on the apical portion of the endothelial cell. [12] These bacteria invade the subarachnoid space with resultant meningitis in 50-70% of cases. In a study of 862 patients, 37-49% developed meningitis without shock, 10-18% developed shock without meningitis, 7-12% developed both, and 10-18% with mild meningococcemia developed neither meningitis nor shock. [13]

Multiple organ failure, shock, and death may ensue as a result of anoxia in vital organs and massive disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Patients with fulminant meningococcemia develop thrombosis and hemorrhage in the skin, the mucous membranes, the serosal surfaces, the adrenal sinusoids, and the renal glomeruli. Adrenal hemorrhage may occur and rarely may be extensive enough to lead to adrenal necrosis (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome).

The Sanarelli-Shwartzman phenomenon has provided valuable insights into the complex relationship between coagulation, inflammation, and the immune response in septic shock. This newfound understanding has the potential to pave the way for improved treatments for sepsis and other inflammatory conditions. Studying the Shwartzman-like reaction in animal models can offer further insights into the pathophysiology of sepsis, potentially benefiting critically ill patients who have experienced various physiological insults. Additionally, exploring the dermal Shwartzman reaction may aid in understanding rare cases of purpura fulminans triggered by uncommon bacterial infections. [14]

Despite challenges and errors in scientific inquiry, advancements in technology are driving accelerated discovery in understanding the human host response to infection. It is critical to learn from past mistakes and adhere to ethical standards in biomedical research to ensure patient safety and well-being. Moreover, thrombosis of glomerular capillaries in the Shwartzman reaction may lead to renal cortical necrosis, a key feature of the disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) model.

Similar thrombi containing numerous leukocytes may be found in the lungs and myocardium.

Primary meningococcal septic arthritis has been described. [15]

Virulence factors

Meningococci have 3 important virulence factors, as follows [16] :

-

Polysaccharide capsule - Individuals with immunity against meningococcal infections have bactericidal antibodies against cell wall antigens and capsular polysaccharide; a deficiency of circulating antimeningococcal antibodies is associated with disease.

-

Lipo-oligosaccharide endotoxin (LOS)

-

Immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1)

A polysaccharide capsule (which also determines the serogroup) enables the organism to resist phagocytosis. [11]

An LOS can be shed in large amounts by a process called blebbing, causing fever, shock, and other pathophysiology. This is considered the principal factor that produces the high endotoxin levels in meningococcal sepsis. Meningococcal LOS interacts with human cells, producing proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). LOS is one of the important structures that mediate meningococcal attachment to and invasion into epithelial cells. [17]

LOS triggers the innate immune system by activating the Toll-like receptor 4MD2 cell surface receptor complex and myeloid in non-myeloid human sounds. The degree of activation of complement then coagulation system is directly related to the bacterial load. [18]

IgA1 protease cleaves lysosomal membrane glycoprotein-1 (LAMP1), helping the organism to survive intracellularly.

Septicemia

The clinical syndrome results from the activation and continued stimulation of the immune system by proinflammatory cytokines. This process is directly caused by bacterial components, such as endotoxins released from the bacterial cell wall, and is indirectly caused by the activation of inflammatory cells. The clinical spectrum of meningococcal septicemia is produced by 4 basic processes (ie, capillary leak, coagulopathy, metabolic derangement, and myocardial failure). Combined, the processes produce multiorgan failure that usually causes cardiorespiratory depression and, possibly, renal, neurologic, and gastrointestinal (GI) failure. [19]

Capillary leak

From presentation until 2-4 days after illness onset, vascular permeability massively increases. Albumin and other plasma proteins leak into the intravascular space and urine, causing severe hypovolemia. This initially is compensated for by homeostatic mechanisms, including vasoconstriction. However, progression of the leak results in decreased venous return to the heart and a significantly reduced cardiac output.

Hypovolemia that is resistant to volume replacement is associated with increased mortality due to meningococcal sepsis. Children with severe disease often require fluid resuscitation involving volumes several times their blood volume in the first 24 hours of the illness, mostly in the first few hours. Pulmonary edema is common and occurs after 40-60 mL/kg of fluid has been given; it is treated with artificial ventilation.

Although capillary leak is the most important clinical event, the underlying pathophysiology is unclear. Some evidence suggests that meningococci and neutrophils cause the loss of negatively charged glycosaminoglycans, which are normally present on the endothelium. Also, the repulsive effect of albumin may be reduced in meningococcal infection; this change allows the protein leak. Albumin is normally confined to the vasculature because of its large size and negative charge, which repels the endothelial negative charge.

Coagulopathy

In meningococcemia, a severe bleeding tendency often is simultaneously present with severe thrombosis in the microvasculature of the skin, often in a glove-and-stocking distribution that can necessitate amputation of digits or limbs. Clinicians face a dilemma because supplying platelets, coagulation factors, and fibrinogen may worsen the process. Meningococcal infection affects the main pathways of coagulation.

Endothelial injury results in platelet-release reactions. Along with stagnant circulation due to local vasoconstriction, platelet plugs form to start the process of intravascular thrombosis. In the plasma, soluble coagulation factors are consumed, and the natural inhibitors of coagulation (eg, the tissue factor pathway inhibitor antithrombin III) are down-regulated; this process further encourages thrombosis.

The protein C pathway probably plays a key role in the pathogenesis of purpura fulminans. A very similar rash occurs in neonates with congenital protein C deficiency and in older children who develop antibodies to protein S following varicella infection. Many patients with meningococcal infection are unable to activate protein C in the microvasculature due to endothelial downregulation of thrombomodulin. [20] Protein C and S levels are low in children with meningococcal disease. However, low levels may occur in patients with septic shock without purpura fulminans. Plasma anticoagulants (tissue factor pathway inhibitor and antithrombin) also are down-regulated in meningococcal sepsis.

The fibrinolytic system in meningococcal disease is down-regulated as well, reducing plasmin generation and removing an aspect of endogenous negative feedback to clot formation. In addition, plasminogen activator inhibitor levels are dramatically increased, further reducing the efficacy of the endogenous tissue plasminogen activator.

Metabolic derangement

Severe electrolyte abnormalities, including hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypophosphatemia, may occur in the setting of severe acidosis.

Myocardial failure

Myocardial function remains impaired even after circulating blood volume is restored and metabolic abnormalities are corrected. Reduced ejection fractions and elevated plasma troponin I levels indicate myocardial damage. A gallop rhythm often is audible, with elevated central venous pressure and hepatomegaly. Hemodynamic studies in patients with meningococcal sepsis have shown that the severity of disease is related to the degree of myocardial dysfunction.

Myocardial failure in meningococcal sepsis is undoubtedly multifactorial, but various proinflammatory mediators (eg, nitric oxide, TNF-alpha, IL-1B) released in sepsis appear to have a direct negative inotropic effect on the heart, depressing myocardial function. A study using new microarray technology showed that IL-6 is the key factor that causes myocardial depression in meningococcemia. [21, 22]

It recently has been demonstrated that meningococcal infection leads to human coronary microvascular thrombosis, vasculitis, and vascular leakage. [23]

Other factors that reduce myocardial function, such as acidosis, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and electrolyte disturbances, all are common in severe meningococcal disease.

Meningitis

Meningococcal meningitis generally has a better prognosis than septicemia. After bacteria enter the meninges, they multiply in the CSF and pia arachnoid. In the early stages of infection, the tight junctions between the endothelial cells that form the blood-brain barrier isolate the CSF from the immune system; this isolation allows bacterial multiplication. Eventually, inflammatory cells enter the CSF and release cytokines that play a central role in the pathophysiology of meningeal inflammation. [2, 19]

Neurologic damage is a consequence of the following 3 main processes:

-

Direct bacterial toxicity

-

Indirect inflammatory processes, such as cytokine release, ischemia, vasculitis, and edema

-

Systemic effects, including shock, seizures, and cerebral hypoperfusion

Cerebral edema may be caused by increased secretion of CSF, diminished reabsorption of CSF, and/or breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Obstructive hydrocephalus may cause increased accumulation of CSF between cells.

Increased ICP secondary to cerebral edema, loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation, and reduced arterial perfusion pressure secondary to shock reduce cerebral blood flow in bacterial meningitis. Reduced cerebral blood flow with vasculitis and thrombosis of cerebral vessels may cause ischemia and neuronal injury.

Etiology

N meningitidis is a gram-negative diplococcus that grows well on blood or chocolate agar supplemented or on selective media, such as Martin-Lewis or Thayer Martin blood and incubated in a moist atmosphere enriched with carbon dioxide.

Oxidase and catalase are biochemical markers for preliminary identification of N meningitidis. Sugar fermentations are required for final identification of the species. N meningitidis ferments glucose and maltose but not sucrose or lactose.

Agglutination reactions with immune serum are used to segregate meningococci into 13 serogroups: A, B, C, D, X, Y, Z, E, W-135, H, I, K, and L, depending on the group-specific capsular polysaccharide antigen. Ninety-eight percent of infections are caused by encapsulated serogroups A, B, C, Y, and W-135, although of these groups, A, B, and C most frequently occur in meningococcal disease. The cell wall of pathogenic meningococci contains a toxic lipopolysaccharide or endotoxin that is chemically identical to enteric bacilli endotoxin.

Transmission

The human nasopharynx is the only known reservoir for N meningitidis. At any given time, up to 10% of the population may be asymptomatic, nasopharyngeal carriers. In China, the weighted carriage rate between 2005-2022 was 2.86% varying between provinces from 0 to 15.5%. [118]

The organism is transmitted via aerosols and nasopharyngeal secretions. Attachment to the nasopharyngeal epithelial cells is aided by meningococci-expressed pili, such as the type IV pilus encoded by pilC, which binds to human cell surface protein CD46.

Meningococci may enter the bloodstream and spread to specific sites, such as the meninges or joints, or disseminate throughout the body. Five percent of individuals become long-term carriers, most of whom are asymptomatic. In outbreaks, the carriage rate of an epidemic strain can reach 90%. The likelihood of acquiring infection is increased 100 to 1000 times in intimate contacts of individuals with meningococcemia.

A study of 14,000 teenagers in the United Kingdom found that attendance at pubs or clubs, intimate kissing, and cigarette smoking each were independently and strongly associated with an increased risk of meningococcal carriage. [24]

Immunity

Passively transferred maternal antibody provides temporary protection to infants for the first 3 to 6 months of life. As the child grows older, asymptomatic exposure to a variety of encapsulated and nonencapsulated N meningitidis strains increases protective bacterial immunity. Most individuals acquire immunity to meningococcal disease by age 20 years; protective IgM and IgG are found in up to 95% of young adults.

An episode of meningococcal disease confers group-specific immunity, but a second episode may be caused by another meningococcal serogroup.

Susceptibility

Complement deficiency

A genetic component to host susceptibility to meningococcemia is becoming more established. IgG antibodies that have specificity for meningococcal polysaccharides mediate bactericidal activity. Complement is needed for the expression of this activity. Terminal complement deficiency is well known to predispose individuals to meningococcemia. Recurrent meningococcemia can occur. [25]

Genetic variants of mannose-binding lectin, a plasma opsonin that initiates another pathway of complement activation, may account for nearly one third of the cases of invasive meningococcal disease.

Meningococcemia is particularly common among individuals with deficiencies of terminal complement components C5-C9 or properdin. These late complement components are required for the bacteriolysis of meningococci.

An estimated 50-60% of individuals with late complement component deficiencies develop at least 1 episode of meningococcal disease. Many of these patients experience multiple episodes of infection.

Acquired complement deficiencies that occur in association with systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple myeloma, severe liver disease, enteropathies, and nephrotic syndrome also predispose to meningococcal infection.

Interleukin abnormalities

Specific genetic polymorphisms likely predispose individuals to mortality in severe sepsis. An association has been described between increased risk for mortality in children with meningococcal disease and polymorphisms in the IL-1 cluster.

An innate anti-inflammatory cytokine profile (low level of TNF and high level of IL-10) also is associated with fatal meningococcal disease.

Coagulation pathway abnormalities

Polymorphisms in the genes that control the coagulation pathways are being evaluated. Patients with the prothrombotic factor V Leiden mutation are at higher risk for thrombotic complications, such as amputations and skin grafting, but do not have increased mortality in meningococcemia.

Other

An increased type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor response to TNF meningococcal septicemia has been demonstrated to result from a polymorphism in the PAI-1 gene.

Another study reported that a toll-like receptor 4 variant genotype was associated with increased mortality in children with invasive meningococcal disease. [26]

Risk factors

Most patients with meningococcal disease are previously healthy; however, patients with certain medical conditions are at increased risk of developing a meningococcal infection.

Risk factors include the following:

-

Close contact with a patient with primary invasive disease: Epidemics among new recruits (eg, in military basic training [boot camp] and college freshmen in dormitories are classic examples of meningococcal spread (see Epidemiology).

-

Recent viral respiratory illness (eg, influenza): A study showed increased rates of meningococcal disease in children during periods of increased influenza and respiratory syncytial virus activity. [27]

-

Smoking or exposure to secondary smoke

-

Host susceptibility: Individuals with a deficiency of complement components C5-C9 and abnormal complement factor H [28]

-

Socioeconomic deprivation

-

Household overcrowding

-

HIV infection (see Epidemiology)

-

It is identified as a sexually transmitted disease in gay men due to prolonged close contact and exchange of secretions, usually serogroup C

Patients with anatomic (splenectomy) or functional asplenia also are at increased risk for invasive meningococcal disease.

Particularly severe cases have occurred during eculizumab therapy. [29]

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

The epidemiological data since 2021 has revealed a concerning surge in cases of meningococcal disease in the United States, surpassing levels seen prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The most recent statistics from 2023 indicate a total of 422 confirmed and probable cases reported, representing the highest number recorded since 2014. This resurgence primarily is attributed to the N meningitidis serogroup Y.

Of particular note is the disproportionate impact of this uptick on specific population subsets, including individuals aged between 30 and 60 years, Black or African-American individuals, and adults living with HIV. Understanding and addressing the factors contributing to these heightened disease rates in these vulnerable populations is crucial for implementing targeted prevention and intervention strategies to mitigate the impact of meningococcal disease on public health. Further research and surveillance efforts are warranted to monitor disease trends and inform effective public health responses to safeguard the well-being of at-risk individuals. [30]

A systematic review of meningococcal carriage rates in the Americas highlighted the United States as having the second-highest rate of 24% between 2001 and 2018. [31] The increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease among young adults in high-stress, close-quarter environments, such as military recruits and college freshmen, is well-recognized. Outbreaks in these populations have prompted vaccine development efforts. [32]

Specific populations, including college freshmen, men who have sex with men (MSM), and individuals with HIV, have experienced a disproportionate burden of meningococcal infections, particularly from serogroup C. The HAART era has shown an increased relative risk of meningococcal disease among individuals with HIV, especially those with lower CD4 counts. Healthcare workers and laboratory personnel face a potential risk of acquiring meningococcal infection without proper protective measures.

Meningococcal disease cases are caused by various serogroups, with outbreaks of serogroup B infections on college campuses following the availability of the quadrivalent conjugated meningococcal vaccine. [33] Patients with complement deficiencies are at higher risk of meningococcal disease caused by serotypes Y and W-135, emphasizing the importance of targeted strategies for at-risk individuals. [34] Understanding these epidemiological trends and risk factors is crucial for guiding public health interventions and improving outcomes in populations vulnerable to meningococcal disease. [35, 36]

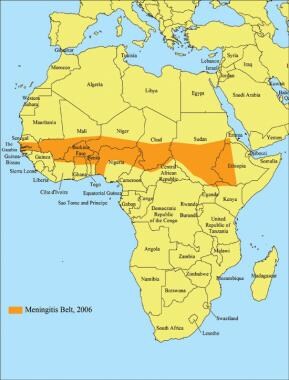

International occurrence

The meningitis belt in sub-Saharan Africa has a well-documented history of experiencing major epidemics of meningococcal disease at intervals ranging from 5 to 12 years, with attack rates peaking at 1,000 cases per 100,000 population during these outbreaks. While the precise risk factors for meningococcal disease epidemics in Africa remain incompletely understood, certain environmental and demographic characteristics create conducive conditions for the spread of the disease. [37]

Factors such as dry and dusty conditions prevalent during the dry season (December to June) in the region, along with the immunological susceptibility of the population, contribute to the increased vulnerability to meningococcal disease outbreaks. Additionally, factors like travel, population displacements, and crowded living conditions further exacerbate the risk of rapid transmission and escalation of meningococcal disease within communities in the sub-Saharan African region. Understanding these environmental and demographic risk factors is crucial for implementing targeted prevention and control measures to mitigate the impact of meningococcal disease epidemics in this high-risk area. [37]

Serogroups A, B, and C are responsible for the majority of meningococcal disease cases worldwide, with varying prevalence in different regions. Serogroups A and C are commonly found in Asia and Africa, while serogroups B and C are prevalent in Europe, North America, and South America.

In China, a notable decrease in meningococcal meningitis cases was observed from 1990 to 2023, with serogroup C being the predominant serogroup during this period. [38] An international outbreak of meningococcal disease associated with serogroup W-135 occurred among travelers returning from the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in 2000 and 2001. [39]

Recent reports indicate a concerning uptick in cases involving non-vaccine serogroup X within Ghana's meningitis belt.43 This shift underscores the importance of ongoing surveillance efforts to monitor changes in serogroup distribution and inform vaccination strategies to address emerging serogroups. Understanding the evolving landscape of meningococcal disease epidemiology worldwide is crucial for effectively combating the disease and protecting at-risk populations.

Areas with frequent epidemics of meningococcal disease. This is known as the meningitis belt of Africa; visitors to these locales may benefit from meningitis vaccine. Image courtesy of CDC.

Areas with frequent epidemics of meningococcal disease. This is known as the meningitis belt of Africa; visitors to these locales may benefit from meningitis vaccine. Image courtesy of CDC.

Meningococcal disease also may be a significant, but underreported, problem in developing Asian countries. [40]

Europe and the United Kingdom

In Europe, invasive meningococcal disease predominantly is caused by serogroup B.

Based on data from 2017-2018, serogroup B remains the most important cause of invasive meningococcal disease in England (54%; 404/755), followed by serogroup W disease (26%), serogroup Y disease (12%), and serogroup C disease (8%). [41]

Climate-related demographics

Meningococcal infections in the United States and Northern Europe are most common in the winter, whereas cases of meningococcal disease in the African meningitis belt increase at the end of the dry season.

Race- and sex-related demographics

Mortality rates may be significantly higher in Blacks than in Whites and Asians. [42]

Meningococcal disease is somewhat more prevalent in males (1.2 cases per 100,000) than in females (1 case per 100,000).

Age-related demographics

In epidemics of meningococcal disease, people of any age may be affected, with the case distribution shifted toward older individuals. [43]

Endemic meningococcal disease is most common in children aged 6-36 months. Children younger than 6 months are protected by maternal antibodies (although occult meningococcemia, an uncommon form of infection, affects children aged 3-24 months). It is rare in neonates, but the incidence in that age group is not known. [44]

Lesions caused by Neisseria meningitis bacteremia on the palm of the hand of a 9-month-old infant. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

Lesions caused by Neisseria meningitis bacteremia on the palm of the hand of a 9-month-old infant. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

A second, less dramatic peak in incidence occurs among teenagers and college students; this may be due to changes in social behavior and increases in close interpersonal contact in these populations. About one third of meningococcal disease cases occur in adults.

In New York City from 1989-2000, the overall incidence rates of meningococcal disease decreased. The median age of patients with meningococcal disease increased from 15 years in 1989-1991 to 30 years in 1998-2000. [45]

Prognosis

Meningococcal disease can progress very quickly and can result in loss of life, neurologic impairment, or peripheral gangrene. Patients with terminal complement component deficiency have a more favorable prognosis. A fatal outcome is highly associated with properdin deficiencies. Coagulopathy with a partial thromboplastin time of greater than 50 seconds or a fibrinogen concentration of less than 150 µg/dL also are markers of poor prognosis.

A multicenter study published in 2006 evaluated the serogroups in children with N meningitidis infection. The researchers found that meningococcal disease continues to result in substantial morbidity and mortality in children. Overall, 55 (44%) of isolates were serogroup B, 32 (26%) were serogroup C, and 27 (22%) were serogroup Y. All but 1 of the isolates (intermediate) were susceptible to penicillin. The overall mortality rate in this pediatric population was 8%. [46]

Cases of meningococcal meningitis without coma or focal neurological deficits have markedly better outcomes. Most of these patients recover completely when appropriate antimicrobial therapy is administered promptly upon presentation.

Isolated meningococcal meningitis (5% mortality rate) has a better prognosis than meningococcal septicemia (10-40% mortality rate).

Patients with higher bacterial loads on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing are more likely to die or have permanent disease sequelae and experience longer hospital stays. [47]

Morbidity

Complications of meningococcal infection include the following:

-

Vasomotor collapse and shock

-

Adrenal hemorrhage and insufficiency

-

Cranial nerve dysfunction, particularly involving the sixth, seventh, and eighth cranial nerves

-

Seizures or deafness in the acute stages of meningitis

-

Postmeningitic epilepsy (rare)

-

Coma

-

Thrombocytopenia

-

Herpes labialis (5-20% of patients with meningococcal disease)

-

Immune complex arthritis involving multiple joints

-

Pericarditis due to immunologic reaction or toxin

-

Cardiorespiratory failure that requires tracheal intubation and inotropic support

-

Renal failure that requires hemofiltration, hemodialysis, or peritoneal dialysis

-

Peritoneal compartment syndrome due to severe abdominal capillary leak that requires placement of a tap

-

Psychological disturbance after intensive care or complications

-

Tamponade due to pericarditis

-

Gangrene

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Purulent conjunctivitis and sinusitis

Complications of meningococcemia may occur at the time of acute disease or during the recovery phase. Patients with fulminant meningococcemia may develop respiratory insufficiency and require mechanical ventilation. Those with severe DIC may bleed into their lungs, urinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract. Ischemic complications of DIC have been reported in up to 50% of survivors of fulminant meningococcemia.

Complications of meningococcal infection include immune complex disease leading to arthritis, pericarditis, myocarditis, and pneumonitis 10-14 days after the primary infection. Up to 5% of patients with meningococcemia develop a nonpurulent pericarditis with substernal chest pain and dyspnea approximately 1 week after the onset of illness. Involvement of the pericardium in meningococcal disease is a well-recognized, but rare, complication. It has been described with N meningitidis serotypes C, B, W-135, and Y. [50]

Meningococcal meningitis may progress to mental obtundation, stupor, or coma, which may be related to increased ICP, and such patients are prone to herniation. Other rare complications of meningitis include acute and delayed venous thrombosis, which usually manifests as a focal neurologic deficit.

Meningococcal infection may spread through the bloodstream and localize in other parts of the body, where it can cause suppurative complications. Septic arthritis, purulent pericarditis, [51] and endophthalmitis [52] can occur but are uncommon.

Meningococcal pneumonia has been described and probably results from aspiration of N meningitidis. The W-135, Y, and B serogroups of meningococci are more likely to cause this form of meningococcal disease, as well as pericarditis and septic arthritis. [53]

Approximately 10% of patients with meningococcal disease develop nonsuppurative arthritis, usually of the knee joints. The nonsuppurative arthritis of meningococcal disease may result from tenosynovitis due to meningococcemia or a postinfectious immunologic process.

Recurrent meningococcal disease has been associated with hereditary deficiencies of various terminal components of the complement system.

Myocarditis is a complication with a high mortality risk. The frequency may be more common than is clinically recognized. [54]

Sequelae

A case-control study examined outcomes in patients who had survived meningococcal disease in adolescence and found that they had poorer mental health, social support, quality of life, and educational outcomes, as well as greater fatigue, than did well-matched control individuals. [55]

A European study found that approximately 4% of survivors of meningococcal infection had sequelae. In the United Kingdom, approximately 5% of survivors have neurologic sequelae, mainly sensorineural deafness. Amputation or skin grafting due to digital or limb ischemia and severe skin necrosis is required in 2-5% of survivors in the United Kingdom.

In the United States in 2005, 11-19% of survivors of meningococcal infection had serious health sequelae, including sensorineural hearing loss, amputations, and cognitive impairment.

-

Dorsum of the hand showing petechiae. Courtesy of Professor Chien Liu.

-

Petechiae on the palm. Courtesy of Professor Chien Liu.

-

Petechiae on lower extremities. Courtesy of Professor Chien Liu.

-

Conjunctival petechiae. Courtesy of Professor Chien Liu.

-

Gram-negative intracellular diplococci. Courtesy Professor Chien Liu.

-

Scattered petechiae in a patient with acute meningococcemia.

-

Purpura in a young adult with fulminant meningococcemia.

-

The legs of a 22-year-old woman in septic shock with a rapidly evolving purpuric rash. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

-

A 9-month-old baby in septic shock with purpuric Neisseria meningitis skin lesions. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

-

The leg of a 9-month-old infant in septic shock with a rapidly evolving purpuric rash. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

-

Neisseria meningitis purpuric lesions on the ear and cheek of a 9-month-old infant who is in septic shock. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

-

Lesions caused by Neisseria meningitis bacteremia on the palm of the hand of a 9-month-old infant. Photo by D. Scott Smith, MD, taken at Stanford University Hospital.

-

Areas with frequent epidemics of meningococcal disease. This is known as the meningitis belt of Africa; visitors to these locales may benefit from meningitis vaccine. Image courtesy of CDC.

-

Child with severe meningococcal disease and purpura fulminans.

-

Flow chart shows guidelines for the emergency management of meningococcal disease in children. These guidelines may be reprinted for use in clinical areas and are available at Meningitis.org.

-

Flow chart shows guidelines for the emergency management of meningococcal disease in adult patients. These guidelines may be reprinted for use in clinical areas and are available from Meningitis.org.

-

Chart for family practice recognition and management of meningococcal disease (courtesy of Meningitis.org).