Practice Essentials

Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases (DPLDs) comprise a heterogenous group of disorders. Clinical, physiologic, radiographic, and pathologic presentations of patients with these disorders are varied (an example is shown in the image below). However, a number of common features justify their inclusion in a single disease category.

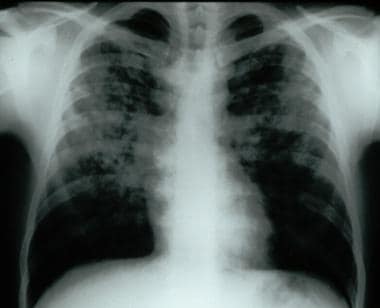

Frontal chest radiograph demonstrating bilateral reticular and nodular interstitial infiltrates with upper zone predominance.

Frontal chest radiograph demonstrating bilateral reticular and nodular interstitial infiltrates with upper zone predominance.

DPLD may be idiopathic, a classic illustration of which is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (see Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis). DPLDs can be described by histopathologic features and include the following: usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP), desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD), smoking-related interstitial fibrosis (SRIF), acute interstitial pneumonitis (AIP) (also known as Hamman-Rich syndrome), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), organizing pneumonia (OP) (see Imaging in Bronchiolitis Obliterans Organizing Pneumonia), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) (see Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonia).

DPLDs can also be grouped based on etiology, which can include occupational/environmental (see Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis), drug, and/or radiation exposure, as well as systemic illness such as connective tissue disease (also known as collagen vascular disease) (see Interstitial Lung Disease Associated With Collagen-Vascular Disease). Other categories of DPLDs includes granulomatous forms, such as sarcoidosis (see Sarcoidosis). Finally, several rare forms of DPLDs exist, including pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) (see Eosinophilic Granuloma (Histiocytosis X)), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (which can be sporadic or associated with tuberous sclerosis) (see Lymphangioleiomyomatosis), and pulmonary fibrosis associated with Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Some of these disorders are categorized as smoking-related lung diseases, including DIP, RB-ILD, SRIF, and PLCH.

This article presents a broad overview on non-IPF DPLDs with an emphasis on those etiologies that result in pulmonary fibrosis not discussed elsewhere in this series.

Pathophysiology

A common pathophysiology has been postulated for these disorders. Although the initial insult or trigger varies among different etiologies, it is thought that later phases share a similar pathophysiology, with an exaggerated inflammatory response, leading to fibroblast proliferation and fibrotic tissue remodeling. [1] Current research indicates that inflammation is less important in IPF, which appears to be primarily a disorder of fibroblast activation and proliferation in response to some as yet unknown trigger(s). [2]

The DPLDs typically manifest with the insidious onset of respiratory symptomatology, although onset can be acute and rapidly progressive, as in COP or AIP.

Pathologically, all DPLDs manifest histologically with disease largely within the interstitial compartment of the lung. However, alveolar and airway architecture also may be disrupted to varying degrees. The histologic patterns of UIP, DIP, RB-ILD, AIP, NSIP, HP, and OP are most common and are focused in the alveolar, lobular, and lobar septa, impacting alveoli, small airways, and pulmonary vasculature.

Genetics

There is published evidence for a genetic basis for a number of DPLDs, including IPF, connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated ILD and HP. The most studied genetic variant associated with DPLDs is a mutated MUC5B, which encodes mucin 5B. It has been associated with the development of both familial pulmonary fibrosis, IPF, and patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD. [3] The MUC5B mutation appears to be more associated with the development of UIP pattern than others and also is present more frequently in patients that develop HP than in the general population. [4] [5]

In addition, several mutations of genes associated with telomerase have been implicated, including TERT, TERC, and RTEL1. It is proposed that pulmonary fibrosis in patients with short telomeres is provoked by a loss of alveolar epithelial cells, resulting in aberrant epithelial cell repair. [6] Mutations of surfactant protein C (SPC) have also been associated with ILD in both adults and children. Although this gene mutation is thought to be familial, de novo mutations are frequent in children. [5]

Investigation of these and other genetic contributors to the pathogenesis of DPLDs is ongoing and in particular may provide further insight into prognosis and therapeutic targets.

Etiology

The causes of DPLDs are varied and numerous, many of which can be grouped as shown below.

DPLDs associated with environmental, occupational, or iatrogenic causes include the following:

-

Pneumoconioses - a group of occupational lung diseases related to inhalational exposures to inorganic dusts (e.g., silicosis, asbestosis, berylliosis, coal worker's pneumoconiosis (black lung disease))

-

HP caused by exposure to protein antigens (e.g., farmer's lung, pigeon-breeder's lung, hot-tub lung)

-

Interstitial lung disease due to exposure to toxic gases, fumes, aerosols, and vapors (e.g., silo-filler's disease)

-

Radiation exposure (ionizing radiation, frequently used in medical therapeutics)

-

Sarcoidosis and other granulomatous diseases (e.g., berylliosis)

DPLDs associated with rheumatologic/connective-tissue diseases are found in the following diseases:

-

Systemic sclerosis (SSc)

-

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

-

Mixed connective-tissue disease (MCTD)

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

-

Myositis (dermatomyositis, polymyositis, anti-synthetase syndrome)

-

Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) - a research definition of ILD among patients who exhibit features of autoimmune or rheumatologic disease but do not meet specific criteria

-

Pulmonary-renal syndromes and vasculitides (i.e. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, also known as Wegener’s Granulomatosis), Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, also known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), or Goodpasture disease) - often included with this group; the predominant manifestation is inflammatory lesiosn of vasculitis (e.g. alveolar hemorrhage, nodules, cavitary lesions), although case series of fibrotic ILD associated with ANCA-associated vasculitis are increasingly reported.

DPLDs related to drug exposure can be caused by:

-

Cytotoxic agents (e.g., bleomycin, busulfan, methotrexate)

-

Antibiotics (e.g., nitrofurantoin, sulfasalazine)

-

Antiarrhythmics (e.g.,, amiodarone, tocainide)

-

Anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., gold, penicillamine)

-

Illicit drugs (e.g., crack cocaine, heroin)

-

Immunotherapy (e.g. checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab)

-

Other immunosuppresants (e.g. infliximab, leflunomide)

DPLDs related to other systemic illnesses can occur with:

-

Hepatitis C

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

-

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Other rare DPLDs include the following:

-

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

-

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) (rare)

-

Eosinophilic pneumonia

-

Sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)

Inherited diseases that can present with DPLDs include the following:

-

Familial pulmonary fibrosis

-

Tuberous sclerosis complex-associated LAM

-

Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome

-

Neurofibromatosis

-

Niemann-Pick disease

-

Gaucher disease

-

Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

-

Dyskeratosis congenita

Certain DPLDs, such as RB-ILD, DIP, SRIF, and PLCH are considered smoking-related.

Epidemiology

Frequency

As a group, diffuse interstitial diseases of the lung are uncommon. Of patients referred to a pulmonary disease specialist, an estimated 10-15% have a DPLD.

In the United States, the 2021 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated over 650,000 cases, with an age-standardized prevalence varying from 101 to 156 cases per 100,000 people among states. [7]

Race

One multicenter study that included 5275 ILD patients in the United States showed a racial and ethnic group breakdown of 83.2% White, 10.2% Black, and 6.7% Hispanic patients. The etiology of ILD varied among racial and ethnic groups, with IPF having the highest prevalence in White patients, HP having the highest prevalence in Hispanic patients, and CTD-ILD having the highest prevalence in Black patients. Black patients were more likely than Hispanic and White patients to be hospitalized, undergo lung transplant, and die at a younger age. [8]

Sex

Evaluation of data from the GBD study showed a higher prevalence of ILD among females, with age-adjusted prevalance of 131.4 per 100,000, compared to 121.3 per 100,000 in males in the United States. [7]

Several DPLDs show sex-related differences in frequency. In general, IPF affects men more than women (at a ratio of 1.5:1), while LAM and pulmonary tuberous sclerosis almost exclusively affect women. Women are much more likely to develop CTD-ILD than men and thus are more likely to experience pulmonary manifestations of those diseases. However, when affected, men with certain rheumatologic diseases (e.g. RA) are more likely to develop pulmonary manifestations than women. The pneumoconioses (e.g., silicosis) are much more common in men than in women, which may be due to higher rates of occupational exposure.

Age

Many of the DPLDs develop over many years and therefore are more prevalent in older adults. For example, most patients with IPF present in the sixth or greater decade of life. Others forms of interstitial lung disease, such as sarcoidosis, LAM, connective-tissue disease–associated lung disease, and inherited forms of lung disease primarily present in younger adults.

Prognosis

The natural history of DPLD varies based on etiology and histologic and imaging pattern, and among individuals with the same diagnosis. Some diseases are insidious in onset and gradual but unrelenting in progression, while other diseases are acute in onset but responsive to therapy.

A typical UIP pattern on imaging or histology is associated with progressive disease and poor prognosis (such as in IPF, which has a mean survival of 2-5 years from diagnosis). Even among different etiologies of ILD that show a typical UIP pattern, there is prognostic value of this pattern compared with other histologic or radiographic patterns.

CTD-ILD has a significantly higher mortality than CTD without ILD. Among different CTDs, mortality is similar, with the exception of SSc-ILD, which has poorer long-term outcomes. [9] The progression of CTD-ILD can vary widely among patients, with some showing stabilization of disease with treatment, while others can have continually progressive disease.

Post-viral fibrotic disease, including disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, has an unclear long-term prognosis, but disease seems to stabilize with resolution of the virus. [10]

In HP, elimination of the causative antigen and systemic steroids can typically stop progression of disease, and sometimes reverse disease process. The causative antigen is often not identified in HP, but when it is identified and removed, patients have better outcomes. [11]

Patient Education

Educate patients about the nature of the specific diagnosis and about potential toxicities of prescribed medications. In addition, many organizations, such as the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, have patient-centered resources to educate patients and caregivers on their diagnosis.

-

Frontal chest radiograph demonstrating bilateral reticular and nodular interstitial infiltrates with upper zone predominance.

-

High-resolution chest CT scan of patient with bilateral reticular and nodular interstitial infiltrates with upper zone predominance.