Practice Essentials

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a rare acute life-threatening illness, caused by a toxin-mediated infectious process linked to toxin-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus or group A Streptococcus (GAS), also called Streptococcus pyogenes. TSS is characterized by high fever, rash, desquamation of palms and soles, hypotension, refractory shock, multiorgan failure, and death. The clinical syndrome can also include severe myalgia, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and nonfocal neurologic abnormalities

See the image below.

A 46-year-old man presented with nonnecrotizing cellulitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. The patient had diffuse erythroderma, a characteristic feature of the syndrome. The patient improved with antibiotics and intravenous gammaglobulin therapy. Several days later, a characteristic desquamation of the skin occurred over palms and soles. Courtesy of Rob Green, MD.

A 46-year-old man presented with nonnecrotizing cellulitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. The patient had diffuse erythroderma, a characteristic feature of the syndrome. The patient improved with antibiotics and intravenous gammaglobulin therapy. Several days later, a characteristic desquamation of the skin occurred over palms and soles. Courtesy of Rob Green, MD.

TSS was first described in children in 1978. [1] Subsequent reports identified an association with tampon use by menstruating women. [2, 3, 4] Menstrual TSS is more likely in women using highly absorbent tampons, using tampons for more days of their cycle, and keeping a single tampon in place for a longer period of time. Over the past decades, the number of cases of menstrual TSS (0.5-1.0 per 100,000 population) has steadily declined; this is thought to be due to the withdrawal of highly absorbent tampons from the market. [5]

Notably, 50% of cases of TSS are not associated with menstruation. Nonmenstrual cases of TSS usually complicate the use of barrier contraceptives, surgical and postpartum wound infections, burns, cutaneous lesions, osteomyelitis, and arthritis. Although most cases of TSS occur in women, about 25% of nonmenstrual cases occur in men.

In the 1980s, Cone initially reported and Stevens subsequently characterized GAS as a pathogen responsible for invasive soft tissue infection ushered by toxic shock–like syndrome. [6, 7] The streptococcal TSS is similar to staphylococcal TSS; however, the blood cultures usually are positive for staphylococci in TSS. Toxin-producing strains of S aureus infect or colonize people who have risk factors for the development of the syndrome. Most cases are related to the staphylococcal toxin, now called TSS toxin-1 (TSST-1).

GAS is an aerobic gram-positive organism that forms chains and is an important cause of soft tissue infections. Diabetes, alcoholism, varicella infections, and surgical procedures all increase the risk of severe GAS infections and hence may potentially increase the risk of TSS. Severe, invasive GAS infections can cause necrotizing fasciitis and spontaneous gangrenous myositis. An increasing number of severe GAS infections associated with shock and organ failure have been reported. These infections are termed streptococcal TSS (STSS). [8] See the image below.

Pathophysiology

TSS is linked mostly to toxin-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus). These toxins act as superantigens in inducing nonclassic activation of T cells by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), leading to nonspecific, polyclonal lymphocyte activation of 5-30% of the total population of T cells, which results in massive release of proinflammatory cytokines. [8]

The most commonly implicated toxins include TSS toxin type-1 (TSST-1) and staphylococcal enterotoxin B.

Almost all cases of menstrual TSS and half of all nonmenstrual cases are caused by TSST-1. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B is the second leading cause of TSS. Other exotoxins such as enterotoxins A, C, D, E, and H contribute to a small number of cases. Seventy to 80% of individuals develop antibody to TSST-1 by adolescence, and 90-95% have such antibody by adulthood. Apart from host immunity status, host-pathogen interaction, local factors (pH, glucose level, magnesium level), and age all have a direct impact on the clinical expression of this toxin-mediated illness.

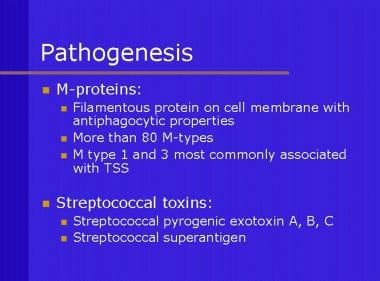

M protein is an important virulent determinant of GAS; strains lacking M protein are less virulent. M protein is a filamentous protein anchored to the cell membrane, which has antiphagocyte properties. M protein types 1, 3, 12, and 28 are the most common isolates found in patients with shock and multiorgan failure; furthermore, three distinct streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins (A, B, C) also have been identified.

Mechanism of shock and tissue destruction

Colonization or infection with certain strains of S aureus and GAS is followed by the production of one or more toxins. These toxins are absorbed systemically and produce the systemic manifestations of TSS in people who lack a protective antitoxin antibody. Possible mediators of the effects of the toxins are cytokines, such as interleukin 1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Pyrogenic exotoxins induce human mononuclear cells to synthesize TNF-alpha, IL-1-beta, and interleukin 6 (IL-6).

Toxins produced by strains of S aureus and GAS act as superantigens. These superantigens interact and activate large numbers of T cells resulting in massive cytokine production.

Normally, an antigen has to be taken up, processed by an antigen-presenting cell, and expressed at the cell surface along with class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC). By contrast, superantigens do not require processing by antigen-presenting cells but instead interact directly with the class II MHC molecule. The superantigen-MHC complex then interacts with the T-cell receptor and stimulates large numbers of T cells to cause an exaggerated, dysregulated cytokine response. Massive production of cytokines leads to refractory shock and tissue injury.

As part of this unusual T cell response, interferon-gamma is also produced, which subsequently inhibits polyclonal immunoglobulin production. This failure to develop antibodies may explain why some patients are predisposed to relapse after a first episode of TSS.

Etiology

Acquisition of infection

Risk factors for the development of staphylococcal TSS are tampon use, vaginal colonization with toxin-producing S aureus, and lack of serum antibody to the staphylococcal toxin. [9] Staphylococcal TSS also has occurred following use of nasal tampons for procedures of the ears, nose, and throat.

The portal of entry for streptococci is unknown in almost one half of the cases. Procedures such as suction lipectomy, hysterectomy, vaginal delivery, and bone pinning have been identified as the portal of entry in many cases. Most commonly, infection begins at a site of minor local trauma, which may be nonpenetrating. Viral infections, such as varicella and influenza, also have provided a portal of entry.

Epidemiology

US frequency

Estimates from population-based studies have documented an incidence of invasive GAS infection of 1.5-5.2 cases per 100,000 people annually. [10] Approximately 8-14% of these patients also will develop TSS. [11] A history of recent varicella infection markedly increases the risk of infection with GAS to 62.7 cases per 100,000 people per year. Severe soft tissue infections, including necrotizing fasciitis, myositis, or cellulitis, were present in approximately half of the patients.

Staphylococcal TSS is much more common, although data on prevalence do not exist. In the United States, from 1979-1996, 5296 cases of staphylococcal TSS were reported. The incidence of menstrual TSS is currently estimated to be 0.5-1.0 per 100,000 population. [5] The incidence of nonmenstrual TSS now exceeds menstrual TSS after the hyperabsorbable tampons were removed from the market.

Race

TSS has occurred in all races, although most cases have been reported from North America and Europe.

Sex

Staphylococcal TSS most commonly occurs in women, usually those who are using tampons.

Age

Some studies have shown no predilection for any particular age for either the streptococcal TSS or staphylococcal TSS. However, other studies have reported staphylococcal TSS to be more common in older individuals with underlying medical problems. In a Canadian survey, staphylococcal TSS accounted for 6% of cases in individuals younger than 10 years compared with 21% in people older than 60 years. [10] Furthermore, menstruation-associated staphylococcal TSS occurred in younger women who were using tampons.

Prognosis

The vast majority of patients with staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome (TSS) recover uneventfully. The mortality rate for staphylococcal TSS is approximately 5%. [12] Since the discontinuation of hyperabsorbable tampons, mortality is rare in patients with menstrual TSS. Contou et al did not report any deaths in a retrospective study of 120 women diagnosed with menstrual TSS between 2005 and 2020. [13] Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome can recur, particularly in the absence of antistaphylococcal therapy and with continued use of tampons. Neuropsychiatric manifestations, such as memory loss and lack of concentration, may persist in some patients.

A retrospective study conducted in a pediatric intensive care unit in India reported a mortality of 27% among children admitted with staphylococcal TSS. The patients in the study who did not survive were more likely to have central nervous system involvement, transaminitis, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and acute kidney injury and to require mechanical ventilation and blood products. [14]

Streptococcal TSS is associated with poorer outcomes than staphylococcal TSS. Mortality rates for streptococcal TSS are 30-70%. [15, 16] Morbidity also is high for streptococcal TSS; in one series, 13 of 20 patients underwent major surgical procedures, such as fasciotomy, surgical debridement, laparotomy, amputation, or hysterectomy. [15]

-

Description of M proteins and streptococcal toxins.

-

Group A streptococci cause beta hemolysis on blood agar.

-

Group A streptococci on Gram stain of blood isolated from a patient who developed toxic shock syndrome. Courtesy of T. Matthews.

-

This schematic shows interaction among T-cell receptor, superantigen, and class II major histocompatability complex. The binding of superantigen to class II molecules and T-cell receptors is not limited by antigen specificity and lies outside the normal antigen binding sites.

-

Progression of soft tissue swelling to vesicle or bullous formation is an ominous sign and suggests streptococcal shock syndrome. Courtesy of S. Manocha.

-

A 46-year-old man presented with nonnecrotizing cellulitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. The leg was incised to exclude underlying necrotizing infection. Courtesy of Rob Green, MD.

-

A 46-year-old man presented with nonnecrotizing cellulitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. This patient also had streptococcal pharyngitis. Courtesy of Rob Green, MD.

-

A 46-year-old man presented with nonnecrotizing cellulitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. The patient had diffuse erythroderma, a characteristic feature of the syndrome. Courtesy of Rob Green, MD.

-

A 46-year-old man presented with nonnecrotizing cellulitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. The patient had diffuse erythroderma, a characteristic feature of the syndrome. The patient improved with antibiotics and intravenous gammaglobulin therapy. Several days later, a characteristic desquamation of the skin occurred over palms and soles. Courtesy of Rob Green, MD.

-

A 58-year-old patient presented in septic shock. On physical examination, progressive swelling of the right groin was observed. On exploration, necrotizing cellulitis, but not fasciitis, was present. The cultures grew group A streptococci. The patient developed severe shock (toxic shock syndrome). The CT scanning helped evaluate the extent of infection and exclude other pathologies, such as psoas abscess, osteomyelitis, and inguinal hernia.

-

A 58-year-old patient presented in septic shock. On physical examination, progressive swelling of the right groin was observed. On exploration, necrotizing cellulitis, but not fasciitis, was present. The cultures grew group A streptococci. The patient developed severe shock (toxic shock syndrome). The CT scanning helped evaluate the extent of infection and exclude other pathologies, such as psoas abscess, osteomyelitis, and inguinal hernia.

-

A 58-year-old patient presented in septic shock. On physical examination, progressive swelling of the right groin was observed. On exploration, necrotizing cellulitis, but not fasciitis, was present. The cultures grew group A streptococci. The patient developed severe shock (toxic shock syndrome). The CT scanning helped evaluate the extent of infection and exclude other pathologies, such as psoas abscess, osteomyelitis, and inguinal hernia.

-

Necrotizing cellulitis of toxic shock syndrome.

-

Soft-tissue infection secondary to group A streptococci, leading to toxic shock syndrome.

-

Extensive debridement of necrotizing fasciitis of the hand.

-

The hand is healing following aggressive surgical debridement of necrotizing fasciitis of the hand.

-

Necrosis of the little toe of the right foot and cellulitis of the foot secondary to group A streptococci.