Background

Campylobacter infections are among the most common bacterial infections in humans. They produce both diarrheal and systemic illnesses. [1] In industrialized regions, enteric Campylobacter infections produce an inflammatory, sometimes bloody, diarrhea or dysentery syndrome. [2]

Campylobacter jejuni is a common food-borne pathogen that can cause diarrhea in all age groups, with peak incidence from age 1 to 5 years. It is a leading cause of food poisoning in the United States, sometimes causing more cases of diarrhea than Salmonella and Shigella combined. In infants, it can also lead to meningitis. In developing regions, diarrhea caused by C jejuni may be watery. [1, 2]

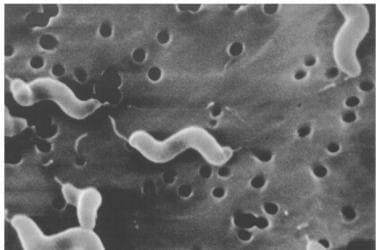

Scanning electron microscope image of Campylobacter jejuni, illustrating its corkscrew appearance and bipolar flagella. Source: Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia.

Scanning electron microscope image of Campylobacter jejuni, illustrating its corkscrew appearance and bipolar flagella. Source: Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia.

Campylobacter species, including C fetus, C coli, and C lari, are known to cause bacteremia and systemic manifestations in adults, particularly those with underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, cirrhosis, cancer, or HIV/AIDS. Although C fetus is less common than C jejuni, it is considered an opportunistic pathogen that primarily affects individuals with predisposing diseases, older adults, and pregnant patients, with pregnant individuals facing a significant risk for fetal loss, with rates as high as 70%. In healthy individuals, infections can be acquired through occupational exposure to animals carrying the bacteria. Patients with immunoglobulin deficiencies are at a higher risk of developing challenging and recurrent infections with Campylobacter species. Hypochlorhydria and achlorhydria also can predispose individuals to Campylobacter infections due to the bacteria's sensitivity to gastric acid. [1]

Campylobacter can manifest as a sexually transmitted infection, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM), leading to gastrointestinal issues such as enterocolitis/proctocolitis syndrome. [1, 3] Bacteremia, including cases caused by Helicobacter species, can occur, with C jejuni often resulting in serious bacteremic conditions in individuals with AIDS. [4, 5] Furthermore, C lari has been associated with mild recurrent diarrhea in children, whereas C upsaliensis can cause diarrhea or bacteremia. Notably, C hyointestinalis, with biochemical features resembling C fetus, may cause sporadic bacteremia in immunocompromised individuals. These clinical presentations highlight the diverse and often severe consequences of Campylobacter infections in various patient populations.

Campylobacter organisms also may be an important cause of traveler's diarrhea, especially in Thailand and surrounding areas of Southeast Asia. In a study of American military personnel deployed in Thailand, more than half of those with diarrhea were found to be infected with Campylobacter species. [6]

Pathophysiology

Campylobacter is said to be prevalent in food animals such as poultry, cattle, pigs, sheep, and ostriches, as well as pets, including cats and dogs.

The known routes of Campylobacter transmission include fecal-oral, person-to-person sexual contact (uncommon), [1] unpasteurized raw milk and poultry ingestion, and waterborne (ie, through contaminated water supplies). Exposure to sick pets, especially puppies, also has been associated with Campylobacter outbreaks. [2]

Transmission of Campylobacter organisms to humans usually occurs via infected animals and their food products. Most human infections result from the consumption of improperly cooked or contaminated foodstuffs. Chickens may account for 50-70% of human Campylobacter infections. Most colonized animals develop a lifelong carrier state.

Campylobacter has been found in shellfish. [7, 8]

The infectious dose is 1000-10,000 bacteria. Campylobacter infection has occurred after ingestion of 500 organisms by a volunteer; however, a dose of fewer than 10,000 organisms is not a common cause of illness. Campylobacter species are sensitive to hydrochloric acid in the stomach. Conditions in which acid secretion is blocked, for example, by antacid treatment or disease, predispose patients to Campylobacter infections.

Symptoms of Campylobacter infection begin after an incubation period of up to a week. The sites of tissue injury include the jejunum, the ileum, and can extend to involve the colon and rectum. Campylobacter jejuni appears to invade and destroy epithelial cells; it is attracted to mucus and fucose in bile, and the flagella may be important in both chemotaxis and adherence to epithelial cells or mucus. Adherence also may involve lipopolysaccharides or other outer membrane components. Such adherence would promote gut colonization. PEB 1 is a superficial antigen that appears to be a major adhesin and is conserved among C jejuni strains.

Some strains of C jejuni produce a heat-labile, cholera-like enterotoxin, which is important in watery diarrhea observed in infections. Infection with the organism produces diffuse, bloody, edematous, and exudative enteritis. The inflammatory infiltrate consists of neutrophils, mononuclear cells, and eosinophils. Crypt abscesses develop in the epithelial glands, and ulceration of the mucosal epithelium occurs.

Cytotoxin production has been reported in Campylobacter strains from patients with bloody diarrhea. In a small number of cases, the infection is associated with the hemolytic-uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura through a poorly understood mechanism. Endothelial cell injury, mediated by endotoxins or immune complexes, is followed by intravascular coagulation and thrombotic microangiopathy in the glomerulus and the gastrointestinal mucosa.

Campylobacter species produce the bacterial toxin cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), which produces a cell block at the G2 stage preceding mitosis. Cytolethal distending toxin inhibits cellular and humoral immunity via the destruction of immune response cells and necrosis of epithelial-type cells and fibroblasts involved in the repair of lesions. This leads to slow healing and results in disease symptoms. [9]

In patients with HIV infection, Campylobacter infections may be more common, may cause prolonged or recurrent diarrhea, and may be more commonly associated with bacteremia and antibiotic resistance.

Campylobacter fetus is covered with a surface S-layer protein that functions like a capsule and disrupts c3b binding to the organisms, resulting in both serum and phagocytosis resistance.

Campylobacter jejuni infections also show recurrence in children and adults with immunoglobulin deficiencies. Acute C jejuni infection confers short-term immunity. Patients develop specific immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies in serum; IgA antibodies develop in intestinal secretions as well. The severity and persistence of C jejuni infections in individuals with AIDS and hypogammaglobulinemia indicate that both cell-mediated and humoral immunity are important in preventing and terminating infection.

Campylobacter infections in kidney transplant recipients have been associated with factors such as the use of corticosteroids for immunosuppression, low eGFR, low lymphocyte counts, and acute rejection.

The oral cavity contains numerous Campylobacter species, such as Campylobacter concisus, that have been associated with a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease. [10, 11] Campylobacter gracilis is associated with periodontal disease, [12] pleuropulmonary disease, and bacteremia [13]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

An estimated 1.5 million cases of Campylobacter infections occur annually in the United States. [14]

In 2020 the incidence of Campylobacter was 20 per 100,000 population. FoodNet surveillance tracks eight foodborne pathogens (including Campylobacter), and a 26% reduction was noted in 2020 as compared to 2017-2019. [15]

International

Campylobacter jejuni infections are extremely common worldwide, although exact figures are not available, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In high-income countries, the incidence has been estimated to be 4.4 to 9.3 per 1000 population. [16] In the UK, 500,000 cases are estimated to occur annually. Campylobacter jejuni and C coli account for 91% and 8% of cases, respectively. [17] The Czech Republic reported the highest national campylobacteriosis rate in 2019, at 126.1 per 100,000 that year. [18]

Mortality/Morbidity

Campylobacter infections usually are self-limited and rarely cause mortality. Exact figures are unavailable, but occasional deaths have been attributed to Campylobacter infections, typically in elderly or immunocompromised persons and secondary to volume depletion in young, previously healthy individuals.

Race

Campylobacter infections have no clear racial predilection.

Sex

Campylobacter organisms are isolated more frequently from males than females. Homosexual men appear to be at increased risk for infection with atypical Campylobacter species such as H cinaedi and H fennelliae.

Age

Campylobacter infections can occur in all age groups.

Studies show a peak incidence in children younger than 1 year and in persons aged 15 to 29 years. The age-specific attack rate is highest in young children. In the United States, the highest incidence of Campylobacter infection in 2010 was in children younger than 5 years and was 24.4 cases per 100,000 population, [19] However, the rate of fecal cultures positive for Campylobacter species is greatest in adults and older children.

Asymptomatic Campylobacter infection is uncommon in adults.

In developing countries, Campylobacter infection is very common in the first 2 years of life. Asymptomatic infection is also more common. [20]

For additional information on pediatric Campylobacter infections, see Campylobacter Infections.

-

Scanning electron microscope image of Campylobacter jejuni, illustrating its corkscrew appearance and bipolar flagella. Source: Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia.