Practice Essentials

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a common genetic neurological disorder characterized by chronic motor and vocal tics beginning before adulthood. [1, 2, 3, 4] Affected individuals typically have repetitive, stereotyped movements or vocalizations, such as blinking, sniffing, facial movements, or tensing of the abdominal musculature. See the image below.

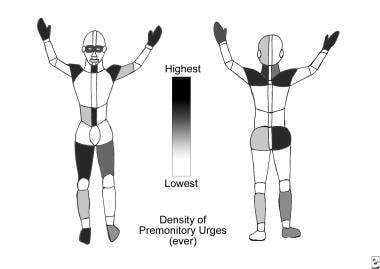

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Graphic shows the relative likelihood of lifetime sensory tics in a given region, as based on self-report of patients with Tourette syndrome. Overt tics are distributed similarly.

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Graphic shows the relative likelihood of lifetime sensory tics in a given region, as based on self-report of patients with Tourette syndrome. Overt tics are distributed similarly.

Signs and symptoms

Tics are abnormal movements or vocalizations that are diverse in presentation. They can be categorized as either motor or vocal/phonic and simple or complex.

Simple motor tics involve a single muscle or group of muscles. Examples of simple motor tics include eye blinking, nose sniffing, coughing, neck twitching or jerking, eye rolling, and jerking or postured movements of the extremities.

Complex motor tics involve movements that often involve multiple muscle groups and may appear as semipurposeful movements or behaviors. Examples of complex motor tics include touching oneself or others, hitting, jumping, shaking, or performing a simulated motor task.

Simple phonic tics are simple vocalizations or sounds. Examples include grunting, coughing, throat clearing, swallowing, blowing, or sucking sounds.

Complex phonic tics are vocalizations of words and/or complex phrases. These verbalizations can be complex and sometimes socially inappropriate.

Behavioral symptoms are common in Tourette syndrome. The 2 most common disorders are OCD and ADHD.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The specific DSM-5 criteria for Tourette’s disorder are as follows [5] :

-

Both multiple motor and 1 or more vocal tics have been present at some time during the illness, though not necessarily concurrently. (A tic is a sudden, rapid, recurrent, nonrhythmic, stereotyped motor movement or vocalization)

-

The tics may wax and wane in frequency but have persisted for more than 1 year since first tic onset

-

The onset is before age 18 years

-

The disturbance is not due to the direct physiologic effects of a substance (eg, cocaine) or a general medical condition (eg, Huntington disease or postviral encephalitis)

The specific DSM-5 criteria for persistent (chronic) motor or vocal tic disorder are as follows [5] :

-

Single or multiple motor or vocal tics (eg, sudden, rapid, recurrent, nonrhythmic, stereotyped motor movement or vocalizations), but not both, have been present at some time during the illness

-

The tics may wax and wane in frequency but have persisted for more than 1 year since first tic onset

-

The onset is before age 18 years

-

The disturbance is not due to the direct physiologic effects of a substance (eg, cocaine) or a general medical condition (eg, Huntington disease or postviral encephalitis)

-

Criteria have never been met for Tourette’s Disorder

The specific DSM-5 criteria for provisional tic disorder are as follows [5] :

-

Single or multiple motor and/or vocal tics (eg, sudden, rapid, recurrent, nonrhythmic, stereotyped motor movement or vocalizations) are present

-

The tics have been present for less than 1 year since the first tic onset

-

The onset is before age 18 years

-

The disturbance is not due to the direct physiologic effects of a substance (eg, stimulants) or a general medical condition (eg, Huntington disease or postviral encephalitis)

-

Criteria have never been met for Tourette’s disorder or persistent (chronic) motor or vocal tic disorder

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatments for tics that have demonstrated efficacy in replicated controlled trials include the following:

-

Dopamine D2 receptor antagonist therapy

-

Dopamine agonist therapy

-

Habit reversal therapy

Patient education is very important for individuals with Tourette syndrome. Counseling and support including cognitive-behavioral therapy and social skills training should also be considered.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a common genetic neurological disorder characterized by chronic motor and vocal tics beginning before adulthood. [1, 2, 3, 4] Affected individuals typically have repetitive, stereotyped movements or vocalizations, such as blinking, sniffing, facial movements, or tensing of the abdominal musculature.

Other neurobehavioral manifestations include attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, poor impulse control, and other behavioral problems. Symptoms wax and wane and vary significantly from one patient to another. Although diagnosis requires the presence of chronic multiple independent motor tics and at least one phonic tic, these are not always the patient's most disabling symptom.

Historical background

A historical example of TS was provided by Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), the author of the first good English dictionary and the subject of Boswell's biography. [6, 7] Many of those who met him were surprised by his repetitive "nervous movements," and he often repeated word fragments or other sounds. His movements and sounds were suppressible, yet they were clearly not voluntary, as they were present even in situations that embarrassed him.

On one occasion, Johnson called his movement "involuntary," yet on another occasion, he called them a "bad habit." He touched objects in a stereotyped fashion, went through a complex ritual on passing through a doorway, and had excessive worries about his religious status and health. Additionally, he suffered from episodes of depression and ate, even in polite company, "like a wild animal." However, he was one of the great minds of his day, and he demonstrated remarkable persistence and clever wit in the face of his adversity.

Some of Johnson's contemporaries believed his odd behavior was a psychological disturbance, while others believed it was a variant of rheumatic chorea. Now, we would consider his symptoms typical of TS.

Go to Pediatric Tourette Syndrome for complete information on this topic.

Current understanding

TS was originally considered a rare psychogenic condition but is now thought to be a relatively common genetic disorder. It remains misunderstood by the lay public, and many people are still unaware that cursing tics (coprolalia) affect only a minority of patients (8%).

One of the first descriptions of tics appeared in 1825, when the French physician Jean Itard described 10 people with repetitive tics, including complex movements and inappropriate words. [8] Subsequently Charcot assigned his resident, George Gilles de la Tourette, to report on several patients treated at the Salpêtrière Hospital for repetitive behaviors. The goal was to define an illness distinct from hysteria and chorea.

In Tourette's 1885 paper, Study of a Nervous Affliction, he concluded that these patients suffered from a new clinical condition: "convulsive tic disorder." [9, 8] Tourette and Charcot thought it was untreatable, chronic, progressive, and hereditary. Although Charcot persisted in his efforts to distinguish "Gilles de la Tourette's tic disease" from other illnesses, his contemporaries generally did not agree.

Over the next century, little progress was made with respect to pathogenesis. A popular theory was that tics resulted from a brain lesion or lesions similar to those seen with rheumatic chorea or encephalitis lethargica. Another commonly proposed idea was that repetitive tics were caused by emotional and psychiatric factors and therefore would be best treated by Freud's psychoanalytic method.

In the United States, the view that TS was a rare, bizarre psychological disorder prevailed for much of the 20th century. In the 1970s, Drs Arthur and Elaine Shapiro, with Bill and Eleanor Pearl of the fledgling Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA), used the efficacy of haloperidol and other clinical data to support the conclusion that TS was a relatively common neurological disorder and not a mental or emotional problem.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology underlying TS remains unknown. Biochemical, imaging, neurophysiologic and genetic studies support the hypothesis that TS is an inherited, developmental disorder of neurotransmission.

The basal ganglia and inferior frontal cortex have been implicated in the pathogenesis of TS, as well as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neuropathological studies, however, have failed to reveal any consistent structural abnormalities in these areas.

Volumetric MRI studies have suggested that the normal asymmetry of the basal ganglia is lost in affected individuals. Healthy right-handed males normally demonstrate a predominance of the left putamen but this appears to be absent in TS, supporting the possibility of a developmental abnormality.

Little is known about the role of the thalamus in the pathogenesis of TS. A recent study using conventional measures of volumes and surface morphology demonstrated enlargement of the thalamus of more than 5% in affected patients of all ages. These findings raise the possibility of activity-dependent hypertrophy and therefore suggest that TS may involve previously unsuspected motor pathways. [10]

Biochemical studies

Abnormalities of central neurotransmitters have been implicated as a cause of TS. Limited post mortem studies have shown low brainstem serotonin, low levels of glutamate in the globus pallidus, and low levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) in the cortex.

Affected individuals have also been shown to have an increased rate of binding of 3H-mazindol to the presynaptic dopamine-uptake-carrier sites. This observation has led some investigators to conclude that TS results from dopaminergic hyperinnervation of the ventral striatum and associated limbic system. Several studies using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) have found an increase in the density of the presynaptic dopamine transporter and the postsynaptic D2 dopamine receptor.

Some neuropathological studies have supported these findings. TS may therefore result from abnormal regulation of dopamine uptake and release.

Noradrenergic pathways have also been studied, in part because tics may improve with the centrally acting alpha2-noradrenergic agonist clonidine. [11] However, studies have failed to demonstrate abnormal concentrations of norepinephrine or its metabolites in serum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or urine in patients with TS.

Serotonin's role in TS remains controversial. Patients have been found to have lower plasma tryptophan levels than normal [12] and some postmortem studies have shown reduced brain tryptophan concentrations.

Unconfirmed results suggest a possible genetic link between TS and a serotonin metabolic enzyme. [13] A [123 I]b-CIT SPECT study suggested lower serotonin transporter binding in patients with TS that seemed to have an inverse correlation with clinical severity. [14] However, the relevance of these findings is unknown. Serotonin-3 receptor genes showed no clear abnormalities in TS. [15]

Most treatments that modify serotonin function (eg, fluoxetine therapy, tryptophan depletion therapy) have not produced consistent responses. However, a double-blind randomized controlled trial of the serotonin-3 receptor antagonist drug ondansetron did suggest efficacy. [16]

Other transmitter systems that may provide insights into tic production include cannabinoid/anandamide receptors, which are located densely in internal globus pallidus (among other areas). Evidence supports the efficacy of cannabinoids in reducing tic severity in some patients. [17]

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most common inhibitory transmitter in the brain. Several studies have shown no abnormalities in patients with TS relative to control subjects.

The role of glutamate, the brain's predominant excitatory transmitter, needs further study. One postmortem report showed markedly different glutamate levels in the internal segment of globus pallidus (GPi), but this finding awaits confirmation. A transgenic mouse model has shown increased stereotypic activity at rest, which was worsened by administration of the noncompetitive glutamate N -methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist MK-801, which is similar to phencyclidine. [18]

The GABA-ergic striatal medium spiny neurons use enkephalin and dynorphin as cotransmitters. Although occasional patients seem to benefit from opioid agonists or antagonists, the data remain sparse. CSF dynorphin concentrations are normal in individuals with TS. [19] One small positron emission tomographic (PET) study demonstrated changes in opioid receptor binding in TS; this remains an interesting area for research. [20]

Dopamine - clinical observations

Substantial evidence indicates that neuroleptic and atypical antipsychotic agents reduce tic severity. Presynaptic dopamine-depleting agents also improve tics, and in some patients, tics may be worsened by neuroleptic withdrawal or, possibly, stimulant use. However, other data do not support a simple hypothesis that dopamine function is hyperactive in individuals with TS.

Tics are not abated with the subsequent development of Parkinson disease. [21] However, in Parkinson disease, dopamine loss is most evident in posterior putamen, [22] whereas caudate and ventral striatum are more implicated in TS.

Furthermore, dopamine receptor agonists have also been used to successfully treat tics, and patients whose tics improved with an agonist had evidence of prolactin inhibition, consistent with a postsynaptic effect. [23, 24, 25] With adequate carbidopa pretreatment, a single dose of levodopa was followed by diminished, not worsened, tic severity. [23]

In summary, clinical evidence suggests that dopaminergic function is abnormal in TS. However, the site of dopamine involvement within the pathway remains unknown.

Dopamine-specific genes

Several studies have examined dopamine-related candidate genes for association with a diagnosis of TS. Studies suggest a possible association with the dopamine D2 or D4 receptors. [26, 27] ; however, specific TS genes remain to be identified.

Dopamine studies

Several groups have studied D2-like dopamine receptor binding in TS by using PET or SPECT. Four studies showed no meaningful differences between TS and control groups with the use of carbon-11 raclopride, [iodine-123]iodo-6-methoxybenzamide (IBZM), [123 I]iodo-2[beta]-carbomethoxy-3[beta]-(4-iodophenyl)tropane (beta-CIT), or11 C 3-N -methylspiperone. [28, 29, 30, 31] (However, a preliminary report from 1 of these studies did describe positive findings.)

Another study compared more severely affected monozygotic twins with TS to their less affected co-twins by using IBZM SPECT and found a correlation of severity with binding in the caudate but not the putamen. [32] This finding suggests that the caudate may play an important role in the pathogenesis of tics. [33]

Studies using a newer D2 ligand ([18 F] N -methylbenperidol) have concluded that D2-like receptor binding is probably normal in TS. However, a number of reports show that presynaptic markers of dopamine innervation may be abnormal in TS. Studies have shown consistently higher concentrations of presynaptic markers or activity in the ventral striatum. [34, 35, 28, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]

These markers have been shown to appear to begin in childhood before treatment has been started. [43] Therefore, in TS, abnormal dopamine production (or abnormal regulation of dopamine production) may lead to abnormal movement and perhaps other altered behavior.

Singer et al demonstrated normal dopamine release at baseline in TS but altered dopamine release in response to a pharmacologic challenge with amphetamine. [40] This observation may explain the essentially normal neurologic function seen in TS when tics are not apparent.

Studies of dopamine breakdown products (homovanillic acid) in the CSF and/or tissue tyrosine hydroxylase levels have failed to consistently demonstrate abnormalities indicative of altered dopamine metabolism.

Dopamine-pharmacologic activation neuroimaging

The author and his colleagues have studied volunteers with chronic tic syndromes and control subjects by using a pharmacologic activation functional magnetic resonance imaging (pharmacologic fMRI, or phMRI) design. [44] This method attempts to map and quantify the brain's responsiveness to a dopamine challenge. Preliminary analyses were complicated by methodological difficulties inherent in the blood oxygenation level–dependent (BOLD) fMRI signal response over long periods (unpublished data). Additional analyses are under way.

A subset of these patients participated in a pharmacologic-cognitive interaction fMRI study. Subjects performed a working memory ("2-back") task or a response inhibition ("go/no-go") task before and again during infusion of levodopa (with carbidopa). Some but not all other studies of patients with TS have shown higher-than-normal commission errors on response inhibition tasks. [45, 46, 47] However, in this study, no differences between groups were observed with the response inhibition task. [48]

As task performance was similar in the 2 groups, the results are best explained by a true difference in brain response between the 2 groups: The TS group apparently requires more activation of several working memory–related regions to sustain normal task performance. These exciting results, if confirmed, suggest that TS patients may have a dopamine-responsive abnormality of brain function in nonmotor as well as motor brain circuits.

Functional imaging studies

In general, the resting metabolic activity of the brain in TS appears to be normal. Studies using blood oxygen level–dependent fMRI comparing activity during a tic with brain activity when tics were absent suggest that tics are associated with activation of broad areas of the neocortex, some limbic areas, the striatum, and the thalamus.

Resting cerebral blood flow or metabolism

Several groups compared patients with TS with control subjects in terms of regional resting brain function, as indexed by blood flow or metabolism. [38] The results suggested no alteration in average whole-brain activity, but some relatively consistent regional differences were found. Increased activity was observed in primary sensorimotor cortex, which may be a nonspecific reflection of excessive movement. All groups found decreased activity in the basal ganglia, perhaps best localized to ventral striatum. [49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]

Some investigators found increased activity in the orbital frontal cortex. [56, 57] Others, however, found decreased orbital activity. [49]

Eidelberg et al examined the correlation of metabolism among specific brain regions and showed differences between TS and controls, some of which related specifically to tic severity. [58]

Correlations with tic severity or tic suppression

In an fMRI study, self-rated intensity of the current urge to tic was correlated with right caudate BOLD signal intensity. [59] Findings also implicated the cingulate cortex.

Similar results emerged from a PET study in which regional cerebral blood flow was correlated with tic frequency in individuals with TS. [60] In this study, atlas-normalized blood flow was searched voxel by voxel for within-subject correlations with the number of tics observed during each of several blood flow scans; tics were associated not only with the expected increased activity in primary motor cortex but also with altered activity in more sensory or volitional brain regions, such as anterior cingulate.

In a [18 F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET study, caudate and thalamus metabolism was inversely correlated with clinical severity. [61]

A case report described fMRI correlates of coprolalia in 1 subject with TS. The results offered support to the hypothesis of a tic-generating circuit model. [62] In ongoing fMRI studies, Stuart Mostofsky at the Kennedy Krieger Institute uses the important control of intentional tic-like movements in people with TS.

Functional imaging with intentional motor activation

In an fMRI study, volunteers with TS performing a simple finger-tapping task had a larger activation of sensorimotor and supplementary motor area than that of control subjects. [63]

By contrast, an fMRI study of precision movement showed decreased activity of supplementary motor area in tic patients versus control subjects. [64]

Functional imaging with behavioral or cognitive activation

In 2001, Rauch and colleagues reported findings from a pilot study in which TS patients (like patients with OCD) showed deficient activation of striatum during implicit learning. [65]

In the same year, Swerdlow and colleagues developed a method for imaging brain function during prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex, a well-studied phenomenon that requires striatal activation. [66]

Neuroanatomic studies

Lesion studies

Several cases of tics beginning after a focal lesion to the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus have been reported. One series described 6 patients who suddenly developed tics, obsessions, and/or compulsions after anaphylactic reaction to wasp stings produced bilateral globus pallidus lesions. [67, 68]

Evaluation of tics secondary to encephalitis or degenerative illnesses

Motor and vocal tics and compulsions frequently were reported in patients who survived the encephalitis lethargica epidemic in the 1910s and 1920s. Similar symptoms also occur in some patients with Huntington disease, Wilson disease, neuroacanthocytosis, or frontal lobe degeneration. Although none of these illnesses cause discrete, circumscribed lesions, these observations support the impression that the basal ganglia and frontal cortex are involved in tic production.

Autopsy studies

A limited number of autopsied cases have shown a reduction in tonically active parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the caudate and putamen. Postmortem studies have also shown a doubling of the parvalbumin-positive projections from the globus pallidus interna to the thalamus.

Although the importance of these findings is uncertain, parvalbumin is known to be a marker for fast-spiking interneurons that have widespread influence. These neurons are thought to be output neurons and their reduction could diminish output from the globus pallidus interna.

In vivo volumetry

Standard neuroimaging studies in TS are unremarkable. However, volumetric MRI has suggested that the normal asymmetry of the basal ganglia is absent.

The largest study of regional brain volumes to date, which involved more than 150 individuals with TS and a similar number of comparison children and adults, showed that subjects with TS had large dorsal prefrontal and parieto-occipital regions and smaller inferior occipital volumes. [69, 70] Symptom severity was best correlated with volume in the orbitofrontal, midtemporal, and parieto-occipital cortex.

TS patients were found to have significantly reduced caudate volumes. [70, 71] The importance of this finding is highlighted by the fact that, on prospective follow-up of patients who had MRI volumetry, smaller caudate volume in childhood correlated significantly with severity of tics, obsessions, and compulsions an average of 7.5 years later. [72]

Another study showed that patients with TS had small right frontal lobes, large left frontal lobes, and more frontal lobe white matter compared with healthy control subjects. [73] Other investigators also found increased frontal white matter. [74]

Two prior studies had selectively examined basal ganglia volumes and had found slightly smaller left putamen volume and a diminution of the normal asymmetry of basal ganglia volume. [69] These findings were not replicated when more- and less-affected twins with TS were compared. [75]

One MRI study revealed abnormal T2 relaxation time in the putamen and caudate nuclei. [76] One case report described a child with a sudden onset of stereotyped behaviors after a streptococcal infection; this child had basal ganglia volumes larger than those of age-matched controls during the acute illness and smaller volumes months later. [77]

Some consistencies arise from these studies. These include decreased caudate volume and, possibly, increased prefrontal white matter and dorsolateral prefrontal gray matter volumes. In one volumetric study, abnormal basal ganglia volumes in a group of patients with TS were entirely attributable to comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). [78]

Similar results were reported from a study of regional brain volumes in relation to streptococcal antibody titers in TS. [79] In other studies, however, the effects of OCD or ADHD were examined and did not explain all of the imaging findings.

The implication is that at a minimum, careful clinical assessment, including information about OCD or ADHD symptoms, is required when the results of any new neuroimaging study are interpreted in individuals with TS. Hopefully, structural imaging will eventually identify a specific anatomic shape that will assist in the identification of responsible genes.

Electrophysiologic studies

Studies using back-averaging techniques have shown that the premovement potential in TS is often absent prior to the appearance of an involuntary movement. This observation supports that the tics are involuntary. [80] Event-related potentials that indicate motor preparation, inhibition of prepotent motor responses, or unexpected events have been variably abnormal in TS patients. [81, 82, 81, 83]

Several laboratories have used short-interval transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to investigate cortical inhibition in TS. In 1997, Ziemann et al showed abnormal cortical inhibition in tic patients. [84] However, in 2001 Moll et al suggested that this was not specific to a TS diagnosis but was accounted for by a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD. [85] Findings from a follow-up study in 2003 suggested that an OCD diagnosis might also account for the original results.

In a 2004 study using transcranial magnetic stimulation, Gilbert et al found that current (recent) severity of tics and hyperactivity in a group of TS subjects was associated significantly and independently with short-interval cortical inhibition. [86] ADHD symptoms, specifically hyperactivity, showed the closest correlation. Repeat studies in the same children replicated these findings and demonstrated their temporal stability. [87] The results have been independently replicated. [88]

Other pathophysiologic studies

Neuropsychological studies have been conducted to study specific areas of cognitive function. Among other goals, this purpose may inform our understanding of the genesis of tics. (The interested reader can consult an excellent review by Como in 2001. [89] )

Independent studies found that patients with TS performed worse than controls on a weather-prediction task that involved habit learning. In this task, cues predict outcomes at probabilities between 0 and 100%; the subject gradually learns to predict outcomes correctly even though feedback to the subject appears to be inconsistent. Worse performance on this task correlates with more severe illness. [90, 91]

In animal and human studies, habit-learning tasks require a healthy striatum. Other forms of memory, including other kinds of procedural learning, are generally normal in TS. [92]

Intentional and reflexive eye movements were studied in TS; the results are summarized as being consistent with the hypothesis that the ability to inhibit or delay planned motor programs is significantly impaired in TS. Altered cortical-basal ganglia circuitry may lead to reduced cortical inhibition, making it harder for TS subjects to withhold the execution of planned motor programs. [93]

Startle reflexes can be studied in a repeatable way and are abnormal in TS, as in OCD. Advances that allow the study of such reflexes in the functional MRI environment and in preclinical models offer hope for rapid screening of potential treatments. [66]

Immune studies related to group A streptococcal infections are discussed below. In addition, a large longitudinal study suggests that 2 cytokines, interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, are associated with recrudescences of symptoms in patients with TS. [94] Whether these are markers specifically for TS symptoms remains to be determined.

Although a pilot microarray study of gene expression in TS peripheral blood did not find a statistically different pattern of expression, the 6 genes with increased expression in TS were all related to immune function. [95] However, none of these same genes were detected in a microarray study of post mortem putamen tissue, suggesting that further study is required in this area. [96]

The high male-to-female ratio in TS (up to 10:1 in some prevalence studies) suggests a possible androgen-mediated effect, perhaps occurring during prenatal development. A study that examined gender identity and gender role behavior in males and females with tic disorders offered some support for this hypothesis: in this study, females demonstrated more gender dysphoria, increased masculine play preferences, and a more typically "masculine" pattern of performance, while males reported increased masculine play preference. [97]

Timing of tics

Peterson and Leckman have drawn attention to the timing of tics. [98] In the course of an office visit, tics tend to occur in bouts rather than being distributed evenly. Similarly, viewed over the course of several months, days with worse tics also tend to cluster together.

A consistent temporal pattern when viewed at any of various time scales is a fractal pattern, a typical feature of a chaotic mathematical system. This suggests the possibility of searching for neuronal firing patterns or other physiologic processes that replicate on even smaller time scales the timing of tics as observed over minutes or months.

Several clinical syndromes are distinct from TS but have overlapping features. These include the repetitive, intrusive thoughts or suppressible but eventually irresistible rituals in OCD, and echophenomena or utilization behavior in patients with catatonia or frontal lobe injury. Conceivably, progress in any of these conditions may yield further insights into the pathophysiology of tic disorders.

Additional insights into tics may be gathered by reference to other illnesses with overlapping features. Tics may be classified as a stereotypic movement disorder, in that the movements are often complex and are repetitive rather than random.

Stereotypies are observed in a number of human and animal situations and may bear some relevance to the anatomy and pathophysiology of TS. Animal models include stallions with inherited repetitive movements, grooming rituals, and self-injury; tethered sows or other animals confined to small quarters; Labrador dogs who repeatedly lick their paws to the point of abrasions; rodents given apomorphine or stimulants; and more recently, rodents injected with plasma from patients with TS. The relevance of these animal models has been reviewed.

In people, a spectrum of stereotyped movement severity ranging from normal to problematic may occur. [99] Simple stereotypies are common in infancy and early childhood. Habits and mannerisms are nearly ubiquitous. However, stereotypies become clearly pathologic in autism or Rett syndrome. Determining why tics chronically persist in a few individuals but briefly appear and then wane in others is important.

A model of tic production

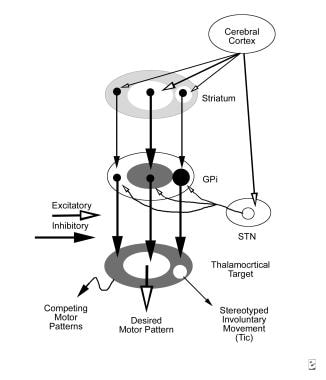

Knowledge about primate basal ganglia anatomy and physiology has been summarized (see the image below). [100, 101, 102] In this view, motor patterns are generated in the cerebral cortex and brain stem. Performance of a specific intended movement includes not only selection of the desired movement but also inhibition of antagonistic movements and of similar movements of neighboring body parts.

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Schematic of the hypothetical reorganization of the basal ganglia output in tic disorders, with excitatory projections (open arrows) and inhibitory projections (solid arrows). Line thickness represents the relative magnitude of activity. When a discrete set of striatal neurons becomes active inappropriately (right), aberrant inhibition of a discrete set of internal segment of globus pallidus (GPi) neurons occurs. The abnormally inhibited GPi neurons disinhibit thalamocortical mechanisms involved in a specific unwanted competing motor pattern, resulting in a stereotyped involuntary movement.

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Schematic of the hypothetical reorganization of the basal ganglia output in tic disorders, with excitatory projections (open arrows) and inhibitory projections (solid arrows). Line thickness represents the relative magnitude of activity. When a discrete set of striatal neurons becomes active inappropriately (right), aberrant inhibition of a discrete set of internal segment of globus pallidus (GPi) neurons occurs. The abnormally inhibited GPi neurons disinhibit thalamocortical mechanisms involved in a specific unwanted competing motor pattern, resulting in a stereotyped involuntary movement.

The basal ganglia are organized so as to inhibit, or apply a "brake" to these undesired motor programs. Normally, the basal ganglia allow selective release of the brake from the desired action. Tics may result from a defect in this braking function. This may be caused by an episode of overactivity in a focal subset of striatal neurons, perhaps in the striatal matrisomes identified by Graybiel and colleagues. [103] The episodic focal overactivity may result from any of various mechanisms acting at any of various locations from cortex to thalamus.

Dopaminergic innervation of striatum has several characteristics that would allow generation of such abnormal epochs of striatal activity; these include dopamine's modulation of the resting membrane potential set point and the influence of dopamine on long-term potentiation or long-term depression (relatively long lasting changes in neuronal excitability based on the prior neuronal inputs).

Finally, this theory is largely derived from studies of the motor circuit involving motor cortex, striatum, internal pallidum, subthalamic nucleus, and ventral thalamus. However, parallel neuronal circuits influence other regions of frontal cortex, including orbitofrontal, medial prefrontal, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. These pathways are relatively separated in the cortex, yet they physically course closer together in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and midbrain.

Lesional and neuroimaging data in individuals with OCD or ADHD implicate abnormalities in nonmotor regions of frontal cortex. Possibly the frequent, but not uniform, occurrence of these symptom complexes in patients with tics represents processes of similar pathology but overlapping anatomy (see image below).

Etiology

Causes of TS may be genetic or nongenetic. The latter category includes cases related to streptococcal infection and cases following other brain insult.

Genetic causes

TS is known to be familial; prevalence of TS in first-degree relatives is 5-15%, or at least 10 times the prevalence in the general population. Chronic motor tics (without vocal tics) are also common in relatives. This is not surprising, since vocal tics are essentially motor tics of the muscles used in speech. In the rest of this article, chronic motor or vocal tic disorder is not distinguished from TS.

Genetic factors are implicated in twin studies, which show that the ratio of concordance in monozygotic versus dizygotic twin pairs is approximately 5:1. [104] By the early 1990s, available data supported a single major autosomal dominant gene with pleiotropic expression (ie, chronic motor tics, TS, or OCD) and incomplete penetrance (about 70% in women, 99% in men). [105, 106] Family linkage methods excluded a single dominant gene in most of the genome, however.

More recent results suggest alternative models. These models include the involvement of several genes rather than one, intermediate penetrance in heterozygotes than in homozygotes, or mixed genetic-environmental causes. [107]

A sibling-pair approach, which may be more sensitive under these conditions, is currently being employed to search for TS genes. The TSA and the National Institutes of Health have supported an international collaborative genetic study using linkage and sibling methods to analyze 500 markers in over 2200 individuals from 269 families. [108] For example, this research has identified DLGAP3 as a promising candidate gene for TS. [109]

Other approaches to identifying specific genes related to TS include examination of families with visible chromosomal abnormalities or a high degree of consanguinity. [110] One such association has been reported, but it affects at most a small minority of people with tics. [111]

Nongenetic causes

Nongenetic causes also must exist, because discordant monozygotic twin pairs are known. Additional evidence for environmental or epigenetic causes includes differences in severity between affected monozygotic twins, with greater severity in the twin with perinatal complications than in the co-twin and cases of secondary (symptomatic) tics with vascular, degenerative, toxic, or autoimmune causes. [112]

The possibility that some, or perhaps many, cases of TS may be caused by an abnormal immune response to streptococcal infection has generated substantial interest.

Streptococcal infections

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, chorea was widely assumed to be usually due to rheumatic fever. The link of chorea to prior streptococcal illness first was proven in the 1950s. The delay occurred partly because in many cases chorea does not follow streptococcal recurrence until several months afterward, and it often occurs without coeval arthritis, carditis, or serologic abnormality.

In the 1970s, patients with Sydenham chorea were demonstrated to have high levels of antibodies that react to human brain. These antibodies have since been shown to cross-react to certain proteins on group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS). [113]

Although tics and chorea can be differentiated clinically, the definitions were less clear in the 19th century. For instance, Charcot and Gilles de la Tourette distinguished tics and chorea primarily on grounds of course and presumed cause rather than phenomenology.

In recent years, interest has been growing in the possibility that streptococcal illness may produce not only chorea but also tics, obsessions, or compulsions. In several cases tics began suddenly after a streptococcal infection, and investigators proposed a research case definition for poststreptococcal autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS). [114]

Although streptococcal infection may cause TS symptoms in a small subgroup of patients, the precise relationship between such infections, antineuronal antibodies, and TS remains unknown.

Some observations support a connection between GABHS infection and tics. [115] OCD occurs more frequently in children with Sydenham chorea than in healthy controls or those who have rheumatic fever without chorea. [116] In a large case-control study, children with OCD or a chronic tic disorder were more than twice as likely as controls to have had a documented GABHS infection in the 3 months prior to the neuropsychiatric diagnosis, and children with multiple GABHS infections in a 12-month period were 13.6 times more likely to later be diagnosed with TS. [117]

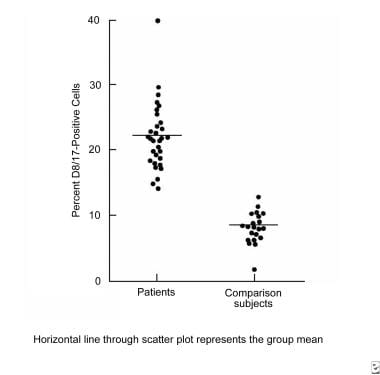

Several patients with either tics or OCD have been found to have high levels of antistreptococcal or anti-DNase antibodies. [114] This is not a nonspecific indicator of distress, since other patient populations do not have these findings. Patients with tics or OCD also have high levels of a B-cell marker (D8/17) that similarly is elevated in Sydenham chorea. [118] Finally, children with TS may have increased levels of circulating antineuronal antibodies (see the image below). [119, 120, 121, 122]

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Immunologic response found in patients with Sydenham chorea is also found in patients with Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Points on the graph represent percent expression of D8/17 antigen on circulating B lymphocytes.

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Immunologic response found in patients with Sydenham chorea is also found in patients with Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Points on the graph represent percent expression of D8/17 antigen on circulating B lymphocytes.

The results above must be tempered by several considerations. [123, 124] First, almost all humans have a GABHS infection at some time, whereas more than 95% never develop OCD or chronic tics, suggesting a substantial role for host factors.

Second, any stressor—including an acute infectious illness—can exacerbate tics. Even without a direct causal link, patients or their parents first may notice tics at a time of stress. The association of TS with immune response is not specific to GABHS (see Pathophysiology). [125]

Third, a positive laboratory result for streptococcal infection can occur without current illness. Additionally, most people with tics simply do not meet a case definition of sudden onset with infection and dramatic subsequent remission. For instance, a nationwide search for such cases for a treatment study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health resulted in only approximately 50 referrals. [126]

Fourth, some laboratory reports contradict the aforementioned results. [127, 128] A large study found no evidence for abnormal serum antineuronal antibodies in patients diagnosed either with PANDAS or with TS. [129]

Streptococcal involvement represents a promising lead that may result in breakthroughs in the understanding of tic pathogenesis. However, treatment based on this hypothesis is not standard care at present. A controlled study showed that, in highly selected patients, OCD can improve after intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. [126] However, achieving true blinding for IVIG administration is difficult, and a placebo effect cannot be excluded. Tics were not affected by treatment in the blinded condition.

Whether antibody-mediated poststreptococcal illness causes most, a few, or no cases of TS is still unknown. In the meantime, a reasonable approach in these cases is to treat acute GABHS infections or rheumatic fever with antibiotics to prevent cardiac sequelae but to avoid invasive immune therapies. A possible exception may be highly select cases of OCD that fit stringent criteria for PANDAS, which might be treated in a research protocol.

Other causes

Several cases of tics beginning after a focal lesion to the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus have been reported. One series described 6 patients who suddenly developed tics, obsessions, and/or compulsions after anaphylactic reaction to wasp stings produced bilateral globus pallidus lesions. [67, 68]

Motor and vocal tics and compulsions frequently were reported in patients who survived the encephalitis lethargica epidemic in the 1910s and 1920s. Similar symptoms also occur in some patients with Huntington disease, Wilson disease, neuroacanthocytosis, or frontal lobe degeneration.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The exact prevalence of TS is not known. This is in part because of the lack of agreement on a precise definition of the disorder. Observational studies have suggested a prevalence of 0.7%, with up to 4.2% of all children having some type of tic disorder.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that the prevalence of a lifetime diagnosis of TS is 3 cases per 1,000 population. This estimate is based on parent report of TS diagnosed by a physician or other healthcare provider from a nationally representative sample of US children and adolescents aged 6-17 years. [130]

International statistics

A recent epidemiological review suggests a 1% international prevalence of TS. [131] However, prevalence figures for TS have varied between 0.4% and 3.8%; in addition, different figures have been reported for some parts of the world and races, with a lower rate in sub-Saharan black Africans.

Several possible reasons for variations in reported rates have been suggested. These include the lack of a definitive diagnosis of TS; the variable manifestations of the syndrome; the methods employed in different epidemiological studies; different cultural propensities of people with tics to seek medical care; and possibly genetic and allelic differences in different races. [132]

Racial differences in incidence

TS has been described in people of many ethnic origins. In the US, the CDC found that a diagnosis of TS was twice as likely for non-Hispanic white persons than for Hispanic and non-Hispanic black persons. However, this observation may be influenced by differences in seeking of healthcare rather than in actual symptomatic prevalence.

Sexual differences in incidence

Boys are more likely than girls to have chronic tics. The male-to-female ratio in TS and in chronic motor tic disorder is approximately 5:1 (between 2:1 and 10:1 in different studies).

Age-related differences in incidence

By definition, TS has onset in childhood (usually age 5-10 y). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) requires onset before age 21. A multicenter study of German families showed that this definition is arbitrary but reasonable. In relatives of TS probands who also had tics, the tics usually started when the individual was younger than 18 years, but 5 relatives had otherwise typical histories for TS with onset after the age of 21 years. [133]

One study of a birth cohort with TS showed that the most common age for tic onset was 9-14 years. [134] The CDC found that diagnosed TS is approximately twice as common in persons 12-17 years old compared with those 6-11 years old.

The modal age of symptom onset increases roughly with complexity: Simple tics are reported earliest in life, while complex tics, compulsions, obsessions, and sensory tics, and/or premonitory sensations tend to develop somewhat later. Generally, simple motor tics (eg, blinking) are first noticed when the individual is approximately 5-10 years old, with vocal tics starting at 8-15 years.

Fortunately, by age 18 years, approximately 50% of patients are essentially free of tics. Tic severity tends to peak in early to mid adolescence and wanes thereafter. Tics may persist into adulthood but their severity is almost always diminished.

Prognosis

TS almost always persists throughout life. Fortunately, by age 18 years, approximately 50% of patients are essentially free of tics. Tic severity tends to peak in early to mid adolescence and wanes thereafter. Tics may persist into adulthood but their severity is almost always diminished.

Many people with tics lead a fairly normal life. However, even mild tics can be distressing.

For example, a patient of one of this article's authors is a man with mild TS who has a successful professional career and a good family life. He is used to his tics and does not prefer any treatment with noticeable adverse effects. However, he finds his symptoms annoying and would rather be free of them if given the choice. He states, "It is like I am on stage 16 hours a day. Every waking moment I am trying not to tic when people are watching." Other people with TS have more severe symptoms. Occasionally, the symptoms can be disabling.

The most common disability is social in nature. [135, 136] Patients with loud vocalizations or large movements either endure substantial criticism or they withdraw from many activities. Prejudice in work and school settings is common.

Tics also interrupt the individual's behavior and thought. Most patients find that they sometimes lose track of a conversation or that they are slow to complete a task because of incessant interruptions by their tics.

Self-injurious behavior is not uncommon. Occasionally, self-injury is intentional and due to a comorbid problem (eg, suicide during an episode of major depression). At times self-injury is pseudointentional; an example is repeatedly hitting one's face as a complex tic.

Perhaps more common than self-injuries are inadvertent injuries. [137, 138] Sometimes, these injuries are due to complex tics or compulsions, such as a need to touch high-voltage wires. Other times, they are due to inattentiveness or impulsivity. (In one of the author's cases, the father of a man with TS does not allow him to use power tools because he had had several near catastrophes.) Inadvertent injuries such as broken bones, cervical arthritis, or shin splints can also occur after simple yet repetitive and/or intense tics.

In clinical samples, most morbidity is due to inattention, impulsivity, obsessions, compulsions, or complex behavioral symptoms such as inappropriate social behavior, rage attacks, or insistence on sameness.

A minority of people with chronic tic syndromes receive disability compensation.

Patient Education

The Tourette Syndrome Association and its local chapters can be a valuable aid in patient education.

-

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Schematic of the hypothetical reorganization of the basal ganglia output in tic disorders, with excitatory projections (open arrows) and inhibitory projections (solid arrows). Line thickness represents the relative magnitude of activity. When a discrete set of striatal neurons becomes active inappropriately (right), aberrant inhibition of a discrete set of internal segment of globus pallidus (GPi) neurons occurs. The abnormally inhibited GPi neurons disinhibit thalamocortical mechanisms involved in a specific unwanted competing motor pattern, resulting in a stereotyped involuntary movement.

-

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Segregated anatomy of the frontal-subcortical circuits: dorsolateral (blue), lateral orbitofrontal (green), and anterior cingulate (red) circuits in the striatum (top), pallidum (center), and mediodorsal thalamus (bottom).

-

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Graphic shows the relative likelihood of lifetime sensory tics in a given region, as based on self-report of patients with Tourette syndrome. Overt tics are distributed similarly.

-

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Immunologic response found in patients with Sydenham chorea is also found in patients with Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Points on the graph represent percent expression of D8/17 antigen on circulating B lymphocytes.

-

Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. In a randomized controlled trial of habit reversal therapy (HRT), results differed significantly from those of a control therapy (massed practice; P < .001, analysis of variance). The HRT group had a 97% reduction in tics at 18-month follow-up, with 80% of patients tic-free.