Practice Essentials

A solitary pulmonary nodule is defined as a discrete, well-marginated, rounded opacity less than or equal to 3 cm in diameter that is completely surrounded by lung parenchyma, does not touch the hilum or mediastinum, and is not associated with adenopathy, atelectasis, or pleural effusion. Lesions larger than 3 cm are considered masses and are treated as malignancies until proven otherwise. See the images below.

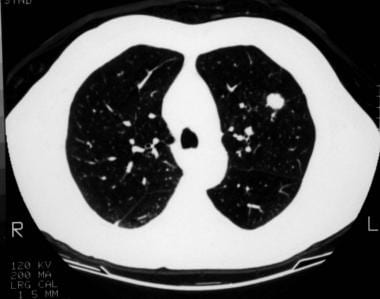

Right upper lobe nodule shows peripheral calcification and high Hounsfield unit enhancement, suggesting that the lesion is a calcified, benign pulmonary nodule.

Right upper lobe nodule shows peripheral calcification and high Hounsfield unit enhancement, suggesting that the lesion is a calcified, benign pulmonary nodule.

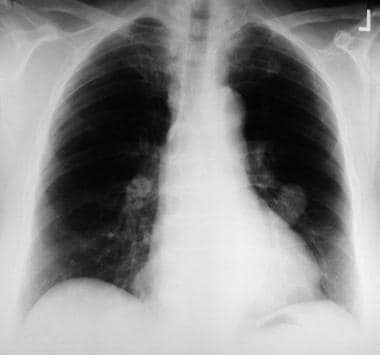

A 1.5-cm coin lesion in the left upper lobe in a patient with prior colonic carcinoma. Transthoracic needle biopsy findings confirmed this to be a metastatic deposit.

A 1.5-cm coin lesion in the left upper lobe in a patient with prior colonic carcinoma. Transthoracic needle biopsy findings confirmed this to be a metastatic deposit.

See The Solitary Pulmonary Nodule: Is It Lung Cancer?, a Critical Images slideshow, for more information on benign and malignant etiologies of solitary pulmonary nodules.

Patients with solitary pulmonary nodules are usually asymptomatic. However, solitary pulmonary nodules can pose a challenge to clinicians and patients. Whether detected serendipitously or during a routine investigation, a nodule on chest imaging raises the following questions:

-

Is the nodule benign or malignant

-

Should it be investigated or observed

-

Should it be surgically resected

Most solitary pulmonary nodules are benign. However, they may represent an early stage of lung cancer. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, accounting for more deaths annually than breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined.

Patients with early lung cancer, when the primary tumor is less than 3 cm in diameter without evidence of lymph node involvement or distant metastasis (stage 1a-c), have a 5-year survival rate of 77-92%. [1] Therefore, prompt diagnosis and management of early lung cancer manifesting as a solitary pulmonary nodule is the the best chance for cure.

Benign lung tumors

Benign lung tumors are a heterogenous group of neoplastic lesions originating from pulmonary structures. These tumors include bronchial adenomas, hamartomas, and a group of uncommon neoplasms (eg, chondromas, fibromas, lipomas, leiomyomas, hemangiomas, teratomas, pseudolymphomas, endometrioma, and bronchial glomus tumors).

Although benign lung tumors do not pose a significant health problem, complications can result if an obstructive lesion predisposes the patient to pneumonia, atelectasis, and hemoptysis.

Determination of whether a lung nodule is benign or malignant based solely on its anatomical location is an incorrect practice. Anatomical location has no predictability on the malignant potential of a tumor. Benign lung tumors can occur in the periphery of the lung, but they can also occur as endobronchial lesions within the tracheobronchial tree.

Characteristics

Neoplastic lesions are characterized by the autonomous proliferation of cells without a response to the normal control mechanisms governing cell growth. An additional characteristic of benign tumors is extension without local tissue invasion or spread to other sites.

Classification

Benign lung tumors can be classified pathologically, but a clinically useful classification would combine location (ie, endobronchial or parenchymal) and information about whether the lesions are single or multiple. Benign lung tumors can also be classified by their presumed origin. Those classifications include the following:

-

Unknown - Hamartoma, clear cell, and teratoma

-

Epithelial – Papilloma and polyps

-

Mesodermal - Fibroma, lipoma, leiomyoma, chondroma, granular cell tumor, and sclerosing hemangioma

-

Other - Myofibroblastic tumor, xanthoma, amyloid, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tumor

Adenomas and hamartomas constitute the largest group of benign lung tumors and, thus, deserve detailed descriptions.

Nodule growth

Generally, a pulmonary nodule must reach 1 cm in diameter before it can be identified on a chest radiograph. For a malignant nodule to reach this size, approximately 30 doublings would have occurred. A lesion at this growth rate may be present for 10 years before discovery. Nodule growth is highly concerning when the nodule volume doubling time (VDT) is greater than 30 days and less than 400 days. [2] The average doubling time for a malignant tumor is 139 days (range, 7-590 d). [3]

Types of Benign Pulmonary Tumors

A solitary pulmonary nodule may be secondary to a wide differential of causes. However, more than 95% are benign [4] ; granulomas (most likely infectious), or benign tumors (most likely hamartomas).

The cause and pathogenesis of benign lung tumors are poorly understood. The nomenclature of benign lung tumors is based on histologic findings.

Hamartomas

Hamartomas (chondroadenomas) are the most common type of benign lung tumor. They occur primarily in adults, although they do occasionally arise in children. Hamartomas are peripherally located. Grossly, they have a firm, marblelike consistency. Histologically, hamartomas generally consist of epithelial tissue and other tissues, such as fat and cartilage. Hamartomas can be easily enucleated, but wedge resection is also appropriate.

Hamartomas consist of haphazardly organized mature cells and tissues. Hamartomas are composed mostly of masses of hyaline cartilage with a myxoid connective tissue, adipose cells, smooth muscle cells, and clefts lined with respiratory epithelium. See the image below.

Bronchial adenomas

Bronchial adenomas make up 50% of all benign pulmonary tumors. The term bronchial adenoma should be discouraged because, when used loosely, it includes carcinoid tumors, adenocystic carcinomas, and mucoepidermoid carcinomas, which, in fact, are low-grade malignant tumors.

Mucous gland adenomas

Mucous gland adenomas are true benign bronchial adenomas. Mucous gland adenomas, which are also called bronchial cystadenomas, arise in the main or local bronchi. Histologically, they consist of columnar cell–lined cystic spaces with a papillary appearance.

Tracheobronchial tumors

Multiple laryngeal papillomatosis is a viral disease of the upper airway that primarily affects children. This disorder has malignant potential and may later spread to the tracheobronchial tree.

Solitary papillomas usually are less than 1.5 cm in diameter. They usually are lobar or segmental in location and are histologically similar to viral papillomatosis.

Inflammatory papilloma is a solitary polypoid mass of granulation tissue that is associated with an underlying pulmonary inflammatory condition.

Granular cell myoblastomas are of neural cell origin. A granular cell myoblastoma contains polygonal or spindle cells with granular cytoplasm. Granular cell myoblastomas tend to be multiple in 10% of cases and are more common in men aged 30-50 years.

Other parenchymal tumors occasionally occurring in the endobronchial tree (eg, leiomyoma, lipoma) almost exclusively are found at an endobronchial location.

Sclerosing hemangiomas

Sclerosing hemangioma is an uncommon tumor derived from the epithelial cells of pneumocytes (terminal bronchiolar cells). This tumor consists of several elements, including solid cellular areas, papillary structures, sclerotic regions, and blood-filled spaces. Sclerosing hemangiomas are most commonly found in middle-aged women. Chest radiography demonstrates a well-defined nodule that is less than 3 cm.

Other mesenchymal tumors include lipoma, leiomyoma, neural tumors, fibroma, benign clear-cell tumor, teratoma, plasma cell granuloma, fibrous histiocytoma, xanthoma, pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma, pulmonary endometrioma, and pseudolymphoma.

Multiple tumors

Many benign lung tumors occasionally have multiple origins. Among these are hamartomas, hyalinizing granulomas, leiomyomas, and sclerosing hemangiomas.

The Carney triad is a syndrome of gastric epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, pulmonary chondromas, and extra-adrenal paragangliomas. The Carney triad mainly affects women.

Pulmonary tumorlets are minute collections of neuroendocrine cells scattered throughout the lung. Pulmonary tumorlets predominantly affect older women.

Clinically significant intrapulmonary chemodectomas apparently are paragangliomas. They behave in a benign fashion.

Etiology of Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

Bearing in mind that the major distinction that must be made is between neoplastic and inflammatory lesions, solitary pulmonary nodules have several causes:

Neoplastic (malignant or benign) tumors can be caused by the following:

-

Bronchogenic carcinoma

-

Adenocarcinoma (including minimally invasive adenocarcinoma)

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

-

Large cell lung carcinoma

-

Small cell lung cancer

-

Metastasis

-

Lymphoma

-

Carcinoid

-

Hamartoma

-

Connective-tissue and neural tumors - Fibroma, neurofibroma, blastoma, and sarcoma

Inflammatory (infectious) nodules can result from the following:

-

Granuloma - Tuberculosis (TB), histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and nocardiosis

-

Lung abscess

-

Round pneumonia

-

Hydatid cyst

Inflammatory (noninfectious) nodules can be caused by the following:

-

Lipoid pneumonia

Congenital nodules can be produced by the following:

-

Pulmonary sequestration

-

Bronchogenic cyst

Other causes of pulmonary nodules include the following:

-

Pulmonary infarct

-

Rounded atelectasis

-

Mucoid impaction

-

Progressive massive fibrosis

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Solitary pulmonary nodules are one of the most common thoracic imaging abnormalities. A revised estimate of over 1 million nodules are detected each year as an incidental finding, either on chest radiographs or thoracic computed tomography (CT) scans. [4] In lung cancer screening studies that enrolled people at high risk for lung cancer, the prevalence of solitary pulmonary nodules ranged from 8-51%. [5]

Approximately 40-50% of solitary pulmonary nodules are malignant. Gould et al reported after a review of the literature that most of these are adenocarcinoma (47%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (22%). Small cell lung cancer makes up only 4% of malignant solitary pulmonary nodules. [6]

Sex- and age-related demographics

Reported series suggest that benign lung tumors affect men more frequently than women (adenoma and hamartoma).

Risk of malignancy increases with age. For individuals younger than 39 years, the risk is 3%. The risk increases to 15% for individuals aged 40-49 years, to 43% for persons aged 50-59 years, and to more than 50% for persons older than 60 years.

Prognosis

Surgical resection is curative for most benign lung tumors. The 5- and 10-year survival rates following surgical resection of typical carcinoid tumors of the lung are above 90%. The 5- and 10-year survival rates for patients with atypical carcinoids are 40-70% and 18-50%, respectively. [7]

In one study, complete bronchoscopic resection for endobronchial carcinoid tumors at 1 and 10 years provided disease-free states at rates of 100% and 94%, respectively. [8] See the images below.

This left lower lobe carcinoid tumor was quite bloody after a percutaneous needle biopsy was performed.

This left lower lobe carcinoid tumor was quite bloody after a percutaneous needle biopsy was performed.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with a left lower lobe carcinoid tumor shows a well-circumscribed lesion.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with a left lower lobe carcinoid tumor shows a well-circumscribed lesion.

Although most solitary pulmonary nodules are benign, they may represent an early stage of lung cancer. While lung cancer survival rates remain dismally low at around 14-18% at 5 years, a diagnosis of early lung cancer (ie, when the primary tumor has a diameter < 3 cm with no lymph node involvement and no distant metastasis [stage 1A]) can be associated with a 5-year survival rate upwards of 80%. Accordingly, the best chance for cure of early lung cancer manifesting as a solitary pulmonary nodule is prompt diagnosis and management.

Possible complications due to benign lung tumors include pneumonia, atelectasis, hemoptysis, hyperinflation, and malignancy.

Patient Education

For patient education information, see the Cancer Center, as well as Bronchoscopy and Bronchial Adenoma.

-

Right upper lobe nodule shows peripheral calcification and high Hounsfield unit enhancement, suggesting that the lesion is a calcified, benign pulmonary nodule.

-

A 1.5-cm coin lesion in the left upper lobe in a patient with prior colonic carcinoma. Transthoracic needle biopsy findings confirmed this to be a metastatic deposit.

-

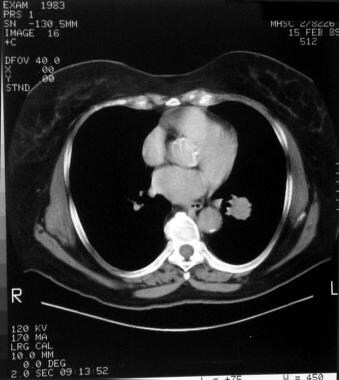

Mediastinal windows of the patient in the previous image

-

Right lower lobe nodule demonstrating central calcification. The most likely diagnosis is histoplasmosis.

-

Close-up view of a right lower lobe nodule demonstrating central calcification. The most likely diagnosis is histoplasmosis.

-

Left upper lobe cavitating solitary nodule eventually identified as active pulmonary tuberculosis from percutaneous needle biopsy findings.

-

A left upper lobe nodule with central lucency and poorly circumscribed margins was diagnosed as actinomycosis based on needle biopsy findings.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient in the previous image. After needle biopsy, the presence of classic sulfur granules confirmed a diagnosis of actinomycosis.

-

A right lower lobe solitary pulmonary nodule that was later identified as a hamartoma.

-

Wedge-shaped peripheral (pleural based) density observed secondary to pulmonary infarction (pulmonary embolism). This is termed the Hampton hump.

-

Left upper lobe 1.5-cm nodule shows negative computed tomography (CT) scan numbers, suggesting fat in the lesion consistent with hamartoma.

-

A left upper lobe solitary pulmonary nodule. The differential diagnosis in such cases is large, but computed tomography (CT) scan findings help to narrow the differentials and establish the diagnosis.

-

Cavitating right lower lobe nodule later confirmed to be primary pulmonary lymphoma. Calcium deposits may also be present in the lesion.

-

This left lower lobe carcinoid tumor was quite bloody after a percutaneous needle biopsy was performed.

-

Lateral radiograph of the patient in the previous image.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with a left lower lobe carcinoid tumor shows a well-circumscribed lesion.

-

A popcorn calcification in the left lung nodule indicates a benign lesion or hamartoma. No further tests or observations were needed for this patient.

-

A 1.5-cm right upper lobe nodule on a computed tomography (CT) scan was determined to be a benign, fibrous lesion on needle biopsy. A follow-up at 2 years showed no change in the size of this lesion.

-

The parenchymal lesion in this computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates low attenuation within the lesion, indicating the presence of fat. Fat density is observed only in hamartoma and lipoid pneumonia. The likely diagnosis is hamartoma

-

This patient has a low risk for malignancy of the right upper lobe nodule. Therefore, continued observation with repeat chest radiographs to establish a growth pattern is the best treatment option.