Practice Essentials

Although initially thought to be a rarity, primary aldosteronism now is considered to be the most common cause of secondary endocrine hypertension (HTN) and one of the most common causes of secondary HTN in general. Litynski reported the first cases, but Conn was the first to well characterize the disorder, in 1956. Conn syndrome, as originally described, refers specifically to primary aldosteronism due to the presence of an adrenal aldosterone-producing adenoma, or aldosteronoma. (See Etiology.)

Based on older data, it was originally estimated that primary aldosteronism accounted for less than 1% of all patients with HTN. Subsequent data, however, indicated that it may actually occur in as many as 10-20% of patients with HTN and up to 40% of patients with resistant hypertension. Furthermore, hyperaldosteronism can also present in patients with no hypertension. The known prevalence of the disease continues to be low because there is minimal amount of screening of it.

Although primary aldosteronism is still a considerable diagnostic challenge, recognizing the condition is critical because primary aldosteronism–associated HTN can often be cured (or at least optimally controlled) with the proper surgical or medical intervention. The diagnosis is generally 3-tiered, involving case detection or screening, confirmation testing, and determination of the specific subtype of primary aldosteronism. (See Presentation, Workup, Treatment, and Medication.)

The most common etiologies of primary aldosteronism can be divided into unilateral and bilateral disease. Distinction between the two major causes of primary aldosteronism is vital because the treatment of choice for each is markedly different. The treatment of choice for unilateral disease is surgical removal of the aldosteronoma, whereas that for bilateral disease is medical therapy. (See Treatment and Medication.)

The most common cause of aldosteronism is bilateral idiopathic adrenal hyperplasia (sometimes referred to as idiopathic hyperaldosteronism [IHA] or primary adrenal hyperplasia [PAH]), followed by aldosteronomas and then by other, rare conditions.

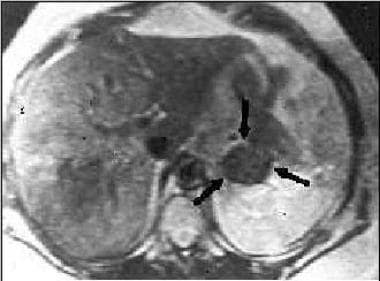

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in a patient with Conn syndrome showing a left adrenal adenoma.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in a patient with Conn syndrome showing a left adrenal adenoma.

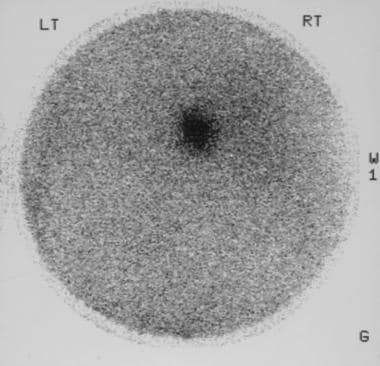

Scintigram obtained by using iodine-131-beta-iodomethyl-norcholesterol (NP-59) in a 59-year-old man with hypertension shows fairly intense radionuclide uptake in the right adrenal tumor. At surgery, a Conn tumor was confirmed.

Scintigram obtained by using iodine-131-beta-iodomethyl-norcholesterol (NP-59) in a 59-year-old man with hypertension shows fairly intense radionuclide uptake in the right adrenal tumor. At surgery, a Conn tumor was confirmed.

Clinically, the distinction between the 2 major causes of primary aldosteronism is vital because the treatment of choice for each is markedly different. While the treatment of choice for aldosteronomas is surgical extirpation, the treatment of choice for IHA is medical therapy with aldosterone antagonists. (See Treatment and Medication.)

Entities known to cause aldosteronism include the following:

-

Aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs), or aldosteronomas (>10 mm) [1]

-

Aldosterone-producing micronodules (< 10 mm)

-

Bilateral idiopathic adrenal (glomerulosa) hyperplasia, or IHA (also known as primary adrenal hyperplasia [PAH])

-

Familial forms of primary aldosteronism

-

Ectopic secretion of aldosterone (The ovaries and kidneys are the 2 organs described in the literature that, in the setting of neoplastic disease, can be ectopic sources of aldosterone, but this is a rare occurrence.)

-

Pure aldosterone-producing adrenocortical carcinomas (very rare; physiologically behave as APAs)

-

Genetic conditions that result in glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism (GRA)

-

Co-secretion adrenal adenomas (glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid secretions)

Aldosterone, by inducing renal reabsorption of sodium at the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), enhances secretion of potassium and hydrogen ions, causing hypernatremia, hypokalemia, and alkalosis. (See Prognosis, Workup, and Treatment.)

Genetic-familial primary aldosteronism

Five genetic-familial varieties of primary aldosteronism exist. Sutherland and colleagues first described the type 1 variety of familial primary aldosteronism, glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism (GRA), in 1966. In GRA, HTN responds clinically to small doses of glucocorticoids in addition to other antihypertensive agents. [2] The type 1 form of familial primary aldosteronism is due to an aberrantly formed chimeric gene product that combines the glucocorticoid-responsive (inhibitable) promoter of the 11beta-hydroxylase gene (CYP11B1) with the coding region of the aldosterone synthetase gene (CYP11B2). Under ambient glucocorticoid levels, the promoter is not fully transcriptionally silenced, and this leads to overexpression of aldosterone synthetase, with subsequent increased synthesis and secretion of aldosterone. (See Etiology and Workup.)

The type 2 variant of familial primary aldosteronism (which is not glucocorticoid sensitive) was first described in 1991. Although the exact genetic abnormality for type 2 primary aldosteronism has not been identified, data suggest that the locus for this disease is on band 7p22. [3]

The type 3 variant of familial primary aldosteronism is due to KCNJ5 (potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 5) potassium channel mutation. This type was described by Lifton’s group in 2011. [4]

The type 4 variant of familial primary aldosteronism is due to CACNA1H mutation. Patients with this disease will have more than one family member with primary aldosteronism.

The type 5 variant of familial primary aldosteronism, known as primary aldosteronism with seizures and neurologic abnormalities (PASNA), results from mutation in CACNA1D.

Signs and symptoms of primary aldosteronism

Patients with primary aldosteronism do not present with distinctive clinical findings, and a high index of suspicion based on the patient's history is vital in making the diagnosis. The findings could include the following:

-

Hypertension (HTN) - This condition almost invariably occurs, although a few rare cases of primary aldosteronism unassociated with HTN have been described in the literature.

-

Hypokalemia - Only 30-40% of patients present with low potassium.

-

Findings related to complications of elevated aldosterone or HTN - These include cardiac failure, hemiparesis due to stroke, cardiac arrythmias, osteoporosis, carotid bruits, abdominal bruits, proteinuria, renal insufficiency, hypertensive encephalopathy (confusion, headache, seizures, changes in consciousness level), and hypertensive retinal changes

Workup in primary aldosteronism

Case detection (first-tier) or screening tests for primary aldosteronism include the following:

-

Plasma aldosterone concentration

-

Plasma renin activity or plasma renin concentration

Confirmatory (second-tier) tests include the following:

-

Oral sodium loading test

-

Saline infusion test

-

Fludrocortisone suppression test

-

Captopril challenge test

Tests for determining the primary aldosteronism subtype (third-tier tests) include the following:

-

Adrenal computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

Adrenal venous sampling (AVS)

-

Dexamethasone suppression test - This test is relevant to determine if there is co-secretion or in cases of rare genetic hyperaldosteronism conditions

Other tests include the following:

-

NP-59 iodo-methyl-norcholesterol scintigraphy: Although fairly difficult to set up and not routinely available, this test can be useful in select cases for distinguishing between adenomas and hyperplasia

-

Adrenal venous sampling: Adrenal venous sampling probably has its greatest utility when adrenal imaging findings are completely normal despite biochemical evidence for primary aldosteronism and in settings in which bilateral adrenal pathology is present on imaging and the biochemistry suggests the presence of a functional aldosteronoma

-

Dexamethasone suppression test: This test is relevant only in the setting of possible familial aldosteronism

-

Metoclopramide (Reglan) test: This is a noninvasive test for distinguishing between aldosteronomas and idiopathic adrenal hyperplasia (IHA)

Management of primary aldosteronism

Pharmacologic therapy includes use of the following:

-

Mineralocorticoid antagonists

-

Amiloride

-

Glucocorticoids (in the setting of GRA)

New drugs such as aldosterone synthesis inhibitors are under study.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for the lateralizable variants of primary aldosteronism, including typical aldosterone-producing adenomas, renin-responsive adenomas (RRAs), and primary adrenal hyperplasia (PAH). An adrenalectomy can be performed via a formal laparotomy or by using a laparoscopic technique (with the latter becoming increasingly common).

Pathophysiology

In primary aldosteronism, there is inappropriate, autonomous, non-suppressible aldosterone secretion. The most important factors that predict the pathophysiologic association of hypokalemia with primary aldosteronism are (1) aldosterone hypersecretion, which acts on the cortical collecting duct to stimulate potassium secretion into the tubular fluid, thus enhancing renal/urinary potassium wasting; [5] (2) adequate intravascular volume, which enables adequate water delivery (tubular flow rate) to the renal distal convoluted tubules (DCTs) and collecting ducts to enable renal potassium loss; and (3) adequate dietary sodium intake, which, in turn, increases total body potassium, renal/ tubular sodium delivery, and, thus, enhances renal potassium loss via the countercurrent transport system.

The absence of one or more of the physiologic circumstances described above may explain the absence of frank hypokalemia in many patients with proven primary aldosteronism, with hypokalemia being present in only 30-40% of people with primary aldosteronism.

The associated metabolic alkalosis in primary aldosteronism is due to increased renal hydrogen ion loss mediated by hypokalemia and aldosterone.

Almost 20% of patients with primary aldosteronism have impaired glucose tolerance resulting from the inhibitory effect of hypokalemia on insulin action and secretion; however, diabetes mellitus is no more common than in the general population.

A study by Moon et al indicated that triglyceride and total cholesterol levels in patients with primary aldosteronism are significantly lower than those in individuals with essential hypertension. Using least-squares means, the triglyceride level in patients with primary aldosteronism was 132.3 mg/dL, versus 157.4 mg/dL in those with essential hypertension, with the total cholesterol levels being 185.5 mg/dL versus 196.2 mg/dL, respectively. These differences existed independently of glycemic status and renal function. [6]

A study by Haze et al indicated that in patients with primary aldosteronism, the ratio of visceral-to-subcutaneous fat volumes is strongly associated with the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The investigators found the greatest correlation between increases in the ratio and decreases in eGFR in patients with the highest plasma aldosterone levels. [7]

Etiology

The cardinal anomaly causing primary aldosteronism syndrome is autonomous (non-suppressible) aldosterone production. In addition to non-suppressible aldosterone production, suppressed and poorly stimulative levels of plasma renin are coexisting with only mildly expanded intravascular and extravascular fluid volume. Normal regulation of aldosterone secretion is mediated to varying degrees by renin, serum potassium and sodium levels, intravascular volume status, and corticotropin.

Regulation of aldosterone production by these factors may be altered in various ways, depending on the subtype of primary aldosteronism. Unilateral disease most often includes APAs, which are greater than 10 mm in size, or aldosterone-producing micronodules, which are less 10 mm in size. Rarely, there may be adrenal cortical carcinoma producing aldosterone or ectopic aldosterone-secreting tumors. Bilateral disease arises from pathology affecting both adrenal glands, as can be seen in familial hyperaldosteronism. A key feature of one type of familial hyperaldosteronism, GRA, is that the aldosterone secretion is corticotropin responsive.

Five distinct genetic-familial varieties of primary aldosteronism exist. These conditions are extremely rare but need to be consider in certain cases.

Type 1

Type 1, glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism (GRA), was first described by Sutherland and colleagues in 1966. In GRA, HTN responds clinically to small doses of glucocorticoids in addition to other antihypertensive agents. [2] The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is suppressed in this form of aldosteronism, and aldosterone is regulated by corticotropin as a result of a chimeric gene fusion of the glucocorticoid-responsive (inhibitable) promoter of the 11beta-hydroxylase gene (CYP11B1) with the coding region of the aldosterone synthetase gene (CYP11B2; which normally does not have such a promoter). Thus, ambient corticotropin levels pathologically overstimulate aldosterone synthesis. [8]

In patients with GRA, the administration of dexamethasone (or any other glucocorticoid) at doses sufficient to suppress excessive corticotropin production results in a reduction in aldosterone synthesis and natriuresis and the eventual correction of the biochemical anomalies of primary aldosteronism. [9] Histologic studies in this disease have shown specific hyperplasia of the zona fasciculata, with concomitant atrophy of the zona glomerulosa.

Type 2

The type 2 variant of familial primary aldosteronism (which is not glucocorticoid sensitive) was first described in 1991. Although the exact genetic abnormality for type 2 primary aldosteronism has not been identified, data suggest that the locus for this disease is on band 7p22. [3] The type 2 variant of familial primary aldosteronism is associated with the familial occurrence or APAs, bilateral IHA, or both.

Type 3

The type 3 variant of familial primary aldosteronism is due to mutation in the KCNJ5 potassium channel-coding gene that results in loss of ion selectivity, cell membrane depolarization, increased Ca2+ entry into adrenal glomerulosa cells, and increased aldosterone synthesis. [4] This type was described by Lifton’s group in 2011. [4]

Type 4

The type 4 variant of familial primary aldosteronism is due to CACNA1H mutation. Patients with this disease will have more than one family member with primary aldosteronism.

Type 5

The type 5 variant of familial primary aldosteronism, known as primary aldosteronism with seizures and neurologic abnormalities (PASNA), results from mutation in CACNA1D.

Sporadic primary aldosteronism

The exact cause of sporadic primary aldosteronism due to an adenoma or hyperplasia is unclear. The existence of trophic factors (eg, endothelins, cytokines) has been postulated in cases of hyperplasia, while somatic mutations are responsible for up to 90% of APAs.

Most sporadic APAs arise from the zona fasciculata, and they often have surrounding glandular hyperplasia close to the adenoma. This suggests that a proliferative cellular response to some presently unidentified paracrine/autocrine factor occurs. Within this zone of hyperplasia, a clonal change in a single cell is believed to take place, thus providing the nidus for the developing adenoma.

Causes

The exact cause of sporadic primary aldosteronism due to an adenoma or hyperplasia is unclear. The existence of trophic factors (eg, endothelins, cytokines) has been postulated in cases of hyperplasia. Somatic mutations of genes leading to growth advantage in the adrenal adenomatous tissue are a possible, but unproven, cause.

In familial forms of primary aldosteronism, the molecular basis of GRA is known. GRA is due to a mutation that results from a hybrid gene product. [3] The 11beta-hydroxylase and aldosterone synthetase genes that are normally located close to each other on chromosome 8 cross over to create a novel hybrid gene product. This hybrid gene consists of the regulatory corticotropin-responsive sequence of the 11beta-hydroxylase gene (CYP11B1) fused to the structural component of the aldosterone synthetase gene (CYP11B2). [2]

Most sporadic aldosteronomas arise from the zona fasciculata, and they often have surrounding glandular hyperplasia close to the adenoma. This suggests that a proliferative response of cells to some presently unidentified paracrine/autocrine factor occurs. Within this zone of hyperplasia, a clonal change in a single cell is believed to take place, thus providing the nidus for the developing adenoma.

The genetic basis of type 2 familial aldosteronism is unclear; however, the locus for this disease has been mapped on 7p22 (band 11q13). [3] This syndrome can histologically manifest as hyperplasia or adenomas.

The genetic basis for type 3 familial aldosteronism has been deciphered. Mutations in the KCNJ5 potassium channel-coding gene results in loss of ion selectivity, cell membrane depolarization, increased Ca2+ entry in adrenal glomerulosa cells, and increased aldosterone synthesis. [4]

The genetic bases for type 4 and 5 familial aldosteronism are CACNA1H and CACNA1D mutations, respectively.

Tertiary aldosteronism

The existence of tertiary aldosteronism as a separate entity remains controversial. The entity is presumed to result from chronic elevations in plasma renin levels and secondary aldosteronism, which eventually establishes a state of autonomous, unregulated aldosteronism with a histologic picture of mixed hyperplasia and adenomas in the affected adrenocortical tissue. This clinicopathologic picture is considered to be the irreversible end-result of prolonged neurohumoral effects on vascular resistance and “terminal” hypertrophy of the aldosterone-producing adrenocortical tissue.

Few well-described cases exist, but in most, the adrenal glands are hyperplastic, often with nodular hyperplasia (which can cause diagnostic confusion). Virtually all of the cases described are in the setting of renal artery stenosis, which complicates further the attribution of the hypertensive state to chronic “inappropriate” aldosterone excess.

Initially, renin levels are elevated, which is typical of secondary aldosteronism. When the tertiary (autonomous) phase develops, the biochemical profile changes to a low-renin/high-aldosterone state. The paradigm is analogous to the pathogenesis of tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

The exact prevalence of primary aldosteronism is unclear, but estimates suggest that 10-20% of essential hypertension cases, and up to 40% of resistant hypertension cases, may be due to primary aldosteronism. The prevalence of primary aldosteronism is probably higher in patients who have a low serum potassium level, in individuals who are elderly, and in persons who have HTN that is resistant to several medications.

International

No evidence demonstrates that primary aldosteronism, in its more common forms, occurs in relative excess in any part of the world. [10, 11, 12]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Primary aldosteronism occurs worldwide. Several reports suggest a higher prevalence in African Americans, persons of African origin, and, potentially, other Black persons. (This appears to be particularly true of the IHA variant of the disease.) The greater prevalence may stem from genetic variation in the ARMC5 gene that may be associated with primary hyperaldosteronism and is more common in the African-American population.

APAs are more common in women than in men, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1. The typical patient with an APA is a woman aged 30-50 years.

Accumulating data for IHA suggest different demographics for this condition, with the idiopathic disease being four times more prevalent in men than in women and peaking in the sixth decade of life.

Prognosis

The morbidity and mortality associated with primary aldosteronism are primarily related to hypokalemia and hypertension (HTN), as well as, evidence indicates, the effects of aldosterone itself. [13, 14] Hypokalemia, especially if severe, causes cardiac arrhythmias, which can be fatal.

Complications from chronic HTN include myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and congestive heart failure. Treatment can also lead to complications, such as drug reactions and complications from surgery.

Evidence exists to show that chronic aldosteronism in and of itself, in the absence of elevated blood pressure (eg, as occurs in secondary aldosteronism), is also associated with increased risk for cardiac injury, including ischemic, hypertrophic, and fibrotic injury. Furthermore, studies have shown that patients with primary aldosteronism are more likely to have or develop left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac arrythmias, osteoporosis, stroke, and acute coronary syndromes than are patients with similar degrees of HTN from other causes. [15, 16]

This was supported by a study by Ohno et al, which indicated that the risk of developing cardiovascular disease is higher in individuals with primary aldosteronism than in those with essential HTN. Cardiovascular disease (including stroke, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure) had a prevalence of 9.4% in patients with primary aldosteronism, greater than that in patients with essential HTN. The difference in stroke prevalence between the two groups was particularly large. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in primary aldosteronism were found to include hypokalemia, unilateral primary aldosteronism, and plasma aldosterone levels at or above 125 pg/mL. [17]

Of course, patients with HTN due to primary aldosteronism are also at risk of developing the entire spectrum of complications of chronic HTN, including hypertensive nephropathy and retinopathy.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in a patient with Conn syndrome showing a left adrenal adenoma.

-

Scintigram obtained by using iodine-131-beta-iodomethyl-norcholesterol (NP-59) in a 59-year-old man with hypertension shows fairly intense radionuclide uptake in the right adrenal tumor. At surgery, a Conn tumor was confirmed.

-

Effects of main antihypertensives on the renin-angiotensin system.

-

Potential causes of primary aldosteronism.

-

Transitional zone adrenocortical steroids.

-

Algorithm for screening for potential primary aldosteronism.

-

Algorithm for confirmation of primary aldosteronism.

-

Algorithm for distinguishing subtypes of primary aldosteronism.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Approach Considerations

- Screening (First-Tier) Tests

- Confirmatory (Second-Tier) Tests

- Determination of Primary Aldosteronism Subtype (Third-Tier Tests)

- CT Scanning and MRI

- NP-59 Iodo-methyl-norcholesterol Scintigraphy

- Adrenal Venous Sampling

- Hydroxycorticosterone and Oxocortisol-Hydroxycortisol Assays

- Fludrocortisone Suppression Test

- Dexamethasone Suppression Test

- Metoclopramide (Reglan) Test

- Additional Laboratory Studies

- Angiotensin-II infusion test

- Histologic Findings

- Show All

- Treatment

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Media Gallery

- References