Practice Essentials

Ependymomas are glial tumors that derive from ependymal cells and can arise anywhere within the central nervous system. These tumors tend to present intracranially in children and spinally in adults. [1] Ependymomas are heterogeneous and individual tumor types can vary significantly in their clinical and molecular characteristics.

The World Health Organization (WHO) divides ependymomas into the following types [2, 3] :

-

Supratentorial ependymoma (WHO Grade 2, 3)

-

Posterior Fossa ependymoma (WHO Grade 2, 3)

-

Spinal ependymoma (WHO Grade 2, 3 (mostly 2)

-

Subependymoma (WHO Grade 1)

Signs and symptoms

The clinical history associated with ependymomas varies according to the age of the patient and the location of the lesion.

Reported signs and symptoms may include the following:

Supratentorial Ependymomas

-

Increased intracranial pressure manifesting as headache, nausea

-

Aphasia

-

Cognitive impairment

-

Mood and personality changes

-

Seizures

Posterior Fossa Ependymomas

-

Ataxia

-

Nystagmus

-

Papilledema

-

Masses in the fourth ventricle: Progressive lethargy, headache, nausea, and vomiting; multiple cranial-nerve palsies (primarily VI-X), as well as cerebellar dysfunction

Spinal Ependymomas

Symptoms vary with the associated spinal level, but generally include:

-

Sensory loss/alteration below the associated level

-

Paralysis that can be unilateral or bilateral

-

Hyper/hyporeflexia

-

Autonomic dysfunction

-

Radicular pain

-

Back pain

-

Bowel/bladder dysfunction

Subependymoma

-

Typically asymptomatic, may resemble above symptoms based on location

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Ependymomas are localized using neuroimaging. Ependymomas are characterized by:

-

Supratentorial ependymoma: appear as heterogenous masses on CT due to cystic areas and calcification; hypointense to white matter with T1 MRI, hyperintense to white matter with T2 MRI

-

Posterior fossa ependymoma: appear similar to supratentorial ependymoma on CT and MRI, but typically present in the fourth ventricle or invade the cervical spinal cord

-

Spinal ependymoma: often present with symmetric spinal cord widening on MRI, calcification is relatively uncommon compared to intracranial ependymoma

Following surgical resection, further characterization of ependymoma may include DNA methylome profiling and histopathological classification. Several markers with prognostic value for ependymoma have been identified.

Ependymoma Classification and Grading:

In 2021, the World Health Organization updated its CNS tumor classification guidelines. Subependymoma remains WHO CNS grade 1. Ependymomas may receive a designation of grade of 2 or 3 depending on histology and molecular analysis.

Prior WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System guidelines published in 2016 included subependymoma, myxopapillary ependymoma, classic ependymoma, and anaplastic ependymoma. Subependymoma and myxopapillary ependymoma were designated WHO grade 1, classical was designated WHO grade 2, and anaplastic was designated WHO grade 3. These guidelines stressed that the distinction between grade 2 and 3 in the setting of ependymoma was controversial.95Anaplastic ependymoma has since been removed from the classification scheme, and myxopapillary ependymoma has been reclassified as grade 2.

The WHO’s 2021 CNS tumor classification guide endorses the use of a “layered report” that takes multiple supporting factors into account, such as the site of the tumor, histopathological classification, and molecular information.

WHO offers the following molecular profiles to guide the diagnosis:

Table 1: WHO Ependymoma Subtypes (Open Table in a new window)

Supratentorial ependymomas |

ZFTA (C11orf95): Zinc Finger Translocation Associated gene |

YAP1: Yes-Associated Protein 1 |

|

Posterior fossa ependymomas |

Posterior Fossa Group A molecular profile |

Posterior Fossa Group B molecular profile |

|

Spinal ependymomas |

NF2: Neurofibromatosis 2 gene |

MYCN Proto-oncogene |

|

MYCN Non-amplified |

|

Subependymoma |

Supratentorial |

Posterior fossa |

|

Spinal |

Management

Treatment of patients with ependymomas depends upon neurosurgical intervention to facilitate definitive diagnosis and to decrease tumor burden. Surgical intervention is often followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation and subsequent surveillance for recurrence.

In terms of surgical care, a gross total resection is optimal. Extent of resection is the best predictor of survival in most ependymoma subtypes. [4, 5] Surgical approach varies with the location of the tumor.

Postoperative adjuvant therapy can include brain or spine radiation, chemotherapy, and radiosurgery. [6, 7, 8, 9] Medical management of ependymomas includes the following [10, 11] :

-

Adjuvant therapy (ie, conventional radiation therapy, radiosurgery, chemotherapy)

-

Steroids for treatment of peritumoral edema

-

Anticonvulsants in patients with supratentorial ependymoma

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) suggests the following for adults [3] :

-

Following suspicion for ependymoma on neuroimaging, maximal safe resection should be performed

-

Following diagnosis of grade 2 or grade 3 ependymoma after resection/biopsy, conduct brain and spine MRI, plus LP to assess for leptomeningeal spread

See the list below:

- LP contraindicated with posterior fossa masses

-

If post-resection neuroimaging is negative for metastasis, administer standard conformal radiation therapy (to tumor area plus 1-2cm margins). If metastasis detected, administer whole craniospinal radiation therapy (or proton therapy to reduce toxicity)

See the list below:

- Spinal ependymomas < WHO Grade 2 do not require radiation therapy if gross total resection was performed and neuroimaging/LP are negative

-

MRI surveillance for recurrence following resection for 5-10 years

-

For recurrent ependymoma, patients who have not received radiation therapy should receive radiation therapy, and if a patient has received radiation therapy, then chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or supportive care should be considered.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Ependymomas are glial tumors that arise from ependymal cells within the central nervous system (CNS). They were first described by Bailey in 1924. Ependymomas can arise anywhere along the neuraxis. and their location varies by age. 90% of ependymomas in children are located intracranially, while 50-60% of adult ependymomas arise in the spine. [12, 13, 14] They are a relatively rare subtype of CNS tumor, making up about 3% of all CNS tumors diagnosed in the United States. [15]

For all ependymomas, the 10-year relative survival rate is noted to be over 85%. [15] This survival rate varies by location. Studies comparing survival rates between supratentorial and posterior fossaependymoma are mixed, but both generally confer a worse prognosis than spinal ependymoma. [12, 16, 17, 18]

Ependymomas are a heterogenous class of CNS tumor and encompass neoplasms that vary widely in their features. Molecular characterization of ependymomas has provided evidence that the classification may encompass tumors with very distinct biological profiles. Incorporating this insight, the 2021 WHO Guidelines subdivided the neoplasm into the types listed below.

Supratentorial ependymoma:

-

ZFTA fusion-positive

-

YAP1 fusion-positive

-

Supratentorial ependymoma not otherwise specified (NOS)

Posterior fossa ependymoma:

-

PF-A

-

PF-B

-

Posterior fossa ependymoma NOS

Spinal ependymoma:

-

MYC-N amplified

-

MYC-N nonamplified

-

Myxopapillary ependymoma

-

Spinal ependymoma NOS

Subependymoma:

-

Supratentorial

-

Posterior fossa

-

Spinal

Each ependymoma anatomic category includes subtypes associated with molecular characteristics of the tumor. Each anatomic category also includes a catch-all category for tumors with histologic features suggestive of ependymoma, but without any of hallmark molecular features.

Myxopapillary ependymomas are considered a biologically and morphologically distinct variant of ependymoma, occurring almost exclusively in the region of the cauda equina. The most recent WHO guidelines elevated myxopapillary tumors from grade 1 to grade 2 in light of new evidence suggesting that these tumors recur at a higher rate than previously believed. [19, 20]

Subependymomas are uncommon, benign lesions that are characterized by slow growth and can arise in any compartment of the CNS. They are considered separately from other ependymoma types and are stratified by location.

Ependymoblastomas are now considered a primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) and are distinct from ependymoma.

See the image below.

Supratentorial ependymomas present in the cerebral hemispheres or within ventricles and are more commonly found in children than adults.

Posterior fossa ependymomas are the most common type of ependymoma overall (though rare in adults,) and are often found in close proximity to cranial nerves and other vital structures, complicating their management.

Spinal ependymomas are most commonly found in adults and are typically considered to have a benign prognosis. They often present as intramedullary masses and can impinge upon nerve roots arising from the terminal spinal cord.

Pathophysiology

Ependymomas are traditionally thought to arise from oncogenetic events that transform normal ependymal cells into tumor phenotypes. Some evidence now suggests that radial glia may be the cells of origin. [21, 22] Significant progress has been made toward delineating mutations that segregate with various tumor phenotypes. While ependymomas exhibit molecular alterations that vary by subtype, some common molecular characteristics include: a loss of loci on chromosome 22, a mutation of p53 in malignant ependymoma, [23] a recurring breakpoint at band 11q13, [24] abnormal karyotypes with frequent involvement of chromosome 6 and/or 16, [25] and NF2 mutations.

Clustering of ependymomas has been reported in some families, with segregation analysis in one family suggesting the presence of an ependymoma tumor suppressor gene in the region of the chromosome 22 locus loss (22pter-22q11.2). [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31]

The pathophysiology of ependymoma varies based on the location and molecular characteristics of the tumor.

Supratentorial Ependymomas

ZFTA-Fusion positive: characterized by gene fusion that interferes with inflammatory pathways, carries a poor prognosis

Yap1-fusion positive: represents the minority of supratentorial ependymomas, characterized by a gene fusion more commonly observed in younger patients and is thought to carry a favorable prognosis. [32]

Posterior Fossa Ependymomas

PF-A: The most common and aggressive subgroup, these occur in young children and appear to lack recurrent somatic mutations.

PF-B: – These tumors tend to present in older children and adolescents. They display frequent large-scale copy number gains and losses but have favorable clinical outcomes.

Spinal Ependymomas

MYCN-amplified: Contains an amplified oncogene that drives rapid proliferation; aggressive subtype with higher likelihood for dissemination and worse prognosis than other spinal subtypes. [33]

Myxopapillary ependymoma: relatively slow-growing tumor with favorable prognosis, but recur at a rate similar to other spinal tumors [20] ; the vast majority arise in the conus medullaris and cauda equina; primarily occur in young adults. [34]

Etiology

Ependymomas have no known environmental cause. A number of genetic mutations have been associated with ependymomas, but a causal relationship between these mutations and tumor progression has not yet been determined. A population based study in Denmark observed that germline mutations in NF1 and NF2 were associated with the development of childhood ependymoma, but fewer than 4% of observed ependymomas were associated with germline mutations. [35]

Epidemiology

Ependymomas are a relatively uncommon form of CNS neoplasm, representing about 3% of CNS tumors diagnosed in the United States overall. However, ependymomas comprise approximately 17% of all spinal tumors. [15]

Some studies have noted a slightly increased incidence of ependymoma in males vs. females. Ependymoma incidence is higher in white people than in other races. [15]

Epidemiological characteristics vary by ependymoma subtype. Intracranial ependymomas, particularly posterior fossa ependymomas, generally present in young children with a median age at diagnosis of 2.5 years. [36] In one large retrospective population study, 66% of spinal tumors occurred in adults over the age of 45, and 39% of all intracranial tumors occurred in children under the age of 12. [37]

Prognosis

The most recent 10-year relative survival rate for ependymoma is 86.7%. [15] This figure varies by age, with patients diagnosed with ependymoma under the age of 14% having a 10 year relative survival of 72%. However, reported 10 year event free survival rates for intracranial pediatric cases are around 60%. [16, 38] These overall rates may therefore reflect differences in prognoses between ependymoma subtypes, which also vary in incidence with age. Supratentorial and posterior fossa ependymomas, which are more common in children, carry a worse prognosis than spinal cord ependymomas, which are more common in adults.

Comparisons between the relative survival rates of supratentorial and infratentorial ependymomas are mixed. Some studies indicate that supratentorial ependymomas are associated with worse mortality than posterior fossa ependymomas in adults, but that these two subtypes have comparable mortality rates in children. [18] Other studies indicate that pediatric patients with posterior fossa ependymomas had improved overall survival compared to supratentorial ependymomas.81 These conclusions are complicated by the fact that ependymomas are rare overall and that posterior fossa ependymomas are more common than supratentorial ependymomas in pediatric patients. [18]

Predictors of long-term survival include extent of resection made at surgery and amount of residual tumor on postoperative imaging. [39] A number of studies [40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47] support the suggestion that the extent of resection is the most important predictor of outcome, independent of the histologic grade of the tumor. Patients with totally resected tumors, primarily of the posterior fossa, had an overall 5-year, progression-free survival rate of nearly 70% compared with 30-40% for those patients with partially resected tumors.

Molecular characteristics of ependymomas have also been proposed as relevant prognostic factors. Ependymomas of the posterior fossa can be further classified into PF-A and PF-B based on their DNA methylome profile. With respect to overall survival at 10 years, patients with PF-A ependymomas have a relatively poor prognosis compared to PF-B (18% vs 51%.) [48] Chromosome 1q gains and 6q deletions are other molecular characteristics that have been associated with worse outcomes within PF-A class ependymomas. [49]

Recurrent tumors are also suggestive of a poor prognosis. One meta analysis of recurrent pediatric ependymomas noted an overall survival of 11 months following recurrence. [50]

-

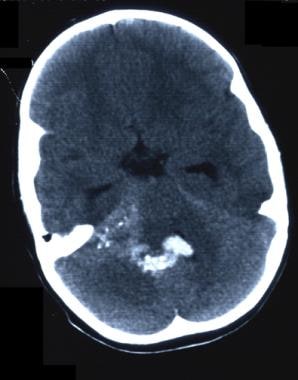

CT scan without contrast. Fourth ventricle ependymoma.

-

CT scan without contrast. Fourth ventricle ependymoma. Note blood in the fourth ventricle.

-

CT scan without contrast in the patient with fourth ventricle ependymoma. Blood has refluxed into the third and lateral ventricles.

-

CT scan without contrast in the patient with fourth ventricle ependymoma. Note blood traversing foramina.

-

T1-weighted MRI. Rare case of a fourth ventricle ependymoma presenting as an intraventricular bleed.

-

T1-weighted MRI without contrast demonstrating ependymoma located in the fourth ventricle.

-

T2-weighted MRI demonstrating ependymoma in the fourth ventricle.

-

Coronal T1-weighted MRI with contrast demonstrating ependymoma of the fourth ventricle.

-

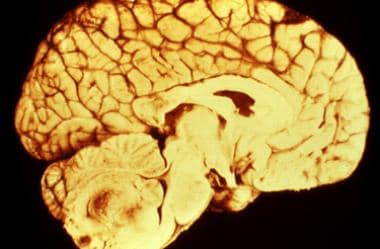

Gross surgical specimen of a fourth ventricle ependymoma.

-

Histologic study of a classic ependymoma. Note the characteristic perivascular pseudorosettes.

-

Cellular ependymoma. Cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio. Few pseudorosettes or paucicellular areas are present.

-

Myxopapillary ependymoma. Clusters of loosely arranged cuboidal cells separated by pools of mucin.

-

Clear cell ependymoma. Round cells with cytoplasmic clearing. This may mimic an oligodendroglioma.

-

MRI images of an ependymoma in the left ventricle. Courtesy of figshare.com [El Majdoub, Faycal; Elawady, Moataz; Blau, Tobias; Bührle, Christian; Hoevels, Mauritius; Runge, Matthias; et al. (2016): Intracranial Ependymoma: Long-Term Results in a Series of 21 Patients Treated with Stereotactic 125Iodine Brachytherapy. PLOS ONE. Dataset. Available at: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Intracranial_Ependymoma_Long_Term_Results_in_a_Series_of_21_Patients_Treated_with_Stereotactic_125_Iodine_Brachytherapy__/117659].

-

MRI image of the sagittal neck with an ependymoma. Modification of a figure from nl-wiki, without author annotations. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons [Author Lucien Monfils, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ependymoma.png].