Practice Essentials

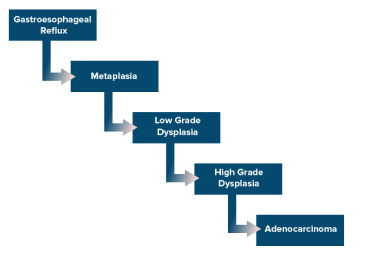

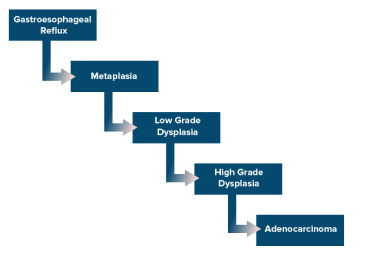

Esophageal cancer is a disease in epidemiologic transition. Until the 1970s, the most common type of esophageal cancer in the United States was squamous cell carcinoma, which has smoking and alcohol consumption as risk factors. Since then, there has been a steep increase in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma, for which the most common predisposing factor is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). [1] See the image below.

Esophageal cancer. Cascade of events that lead from gastroesophageal reflux disease to adenocarcinoma.

Esophageal cancer. Cascade of events that lead from gastroesophageal reflux disease to adenocarcinoma.

Signs and symptoms

Presenting signs and symptoms of esophageal cancer include the following:

-

Dysphagia (most common); initially for solids, eventually progressing to include liquids (usually occurs when esophageal lumen < 13 mm)

-

Weight loss (second most common) due to dysphagia and tumor-related anorexia.

-

Bleeding (leading to iron deficiency anemia)

-

Epigastric or retrosternal pain

-

Bone pain with metastatic disease

-

Hoarseness (due to involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve)

-

Persistent cough

-

Intractable coughing or frequent pneumonia (due to tracheobronchial fistulas caused by direct invasion of tumor through the esophageal wall and into the mainstem bronchus)

Physical findings include the following:

-

Typically, normal examination results unless the cancer has metastasized

-

Hepatomegaly (from hepatic metastases)

-

Lymphadenopathy in the laterocervical or supraclavicular areas (reflecting metastasis)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies such as complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel focus principally on patient factors that may affect treatment (eg, nutritional status, kidney function).

Imaging studies used for diagnosis and staging include the following:

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD; allows direct visualization and biopsies of the tumor)

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS; most sensitive test for T and N staging; used when no evidence of M1 disease)

-

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and chest with contrast (for assessing lung and liver metastasis and invasion of adjacent structures)

-

Pelvic CT scan with contrast if clinically indicated

-

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning (for staging)

-

Bronchoscopy (if tumor is at or above the carina, to help exclude invasion of the trachea or bronchi)

-

Laparoscopy and thoracoscopy (for staging regional nodes)

-

Barium swallow (very sensitive for detecting strictures and intraluminal masses, but now rarely used)

For staging information, see Esophageal Cancer Staging.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of esophageal cancer varies by disease stage, as follows:

-

Stage I-III (locoregional disease) - Available modalities are endoscopic therapies (eg, mucosal resection or ablation), esophagectomy, preoperative chemoradiation, and definitive chemoradiation.

-

Stage IV – Systemic chemotherapy with palliative/supportive care for patients with ECOG performance score of 2 or less and palliative/supportive care only for patients with ECOG performance score of 3 or more.

Indications for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer include the following:

-

Esophageal cancer in a patient who is a candidate for surgery (esophagectomy)

Contraindications for surgical treatment include the following:

-

Metastasis to N2 (celiac, cervical, supraclavicular) nodes or solid organs (eg, liver, lungs)

-

Invasion of adjacent structures (eg, recurrent laryngeal nerve, tracheobronchial tree, aorta, pericardium)

-

Severe associated comorbid conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease)

Surgical options include the following:

-

Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy (laparotomy plus right thoracotomy)

-

McKeown esophagogastrectomy (right thoracotomy plus laparotomy plus cervical anastomosis)

-

Minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy (laparoscopic approach)

-

Minimally invasive McKeown esophagogastrectomy (laparoscopic approach)

-

Robotic minimally invasive esophagogastrectomy

-

Transhiatal esophagectomy (THE)

-

Transthoracic/transabdominal esophagectomy with anastomosis in chest or neck

Palliative care options for patients who are not candidates for surgery are as follows:

-

Chemotherapy

-

Radiotherapy

-

Laser therapy

-

Stents

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Esophageal cancer is a devastating disease. It is the 11th most commonly diagnosed cancer and 7th most common cause of cancer death worldwide, leading to 445,000 deaths in 2022. [4] Although some patients can be cured, the treatment for esophageal cancer is protracted, diminishes quality of life, and is lethal in a significant number of cases.

The principal histologic types of esophageal cancer are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma. SCC is the most common histology in Eastern Europe and Asia, while adenocarcinoma is most common in North America and Western European countries.

Squamous cells line the entire esophagus, so SCC can occur in any part of the esophagus, but it often arises in the upper half. Adenocarcinoma typically develops in specialized intestinal metaplasia (Barrett metaplasia) that develops as a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD); thus, adenocarcinoma typically arises in the lower half of the distal esophagus and often involves the esophagogastric junction.

Esophageal lymphoma is rare, accounting for less than 1% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas. Involvement of the esophagus is most commonly the result of contiguous spread from the proximal stomach, adjacent mediastinal lymph nodes, or cervical lymph nodes. Primary esophageal lymphoma is even rarer. [5]

Treatment history and controversy

Surgery has traditionally been the treatment for esophageal carcinoma. The first successful resection was performed in 1913 by Torek. [6] In the 1930s, Ohsawa in Japan and Marshall in the United States were the first to perform successful single-stage transthoracic esophagectomies with continent reconstruction. [7, 8]

The ideal treatment for localized esophageal cancer is sometimes debated across practice cultures and subspecialties. Proponents of surgical treatment argue that resection is the only treatment modality to offer curative intent; proponents of the nonsurgical approach claim that esophagectomy has a prohibitive index of mortality and that esophageal cancer is an incurable disease.

Analysis of the National Cancer Database from 2004 to 2014 identified 18,459 patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer, including 708 who were recommended for surgery but refused it. Median survival was 32 months for patients undergoing esophagectomy, versus 21 months in patients who refused surgery (P < 0.001). [9]

Current guidelines recommend surgery—resection or esophagectomy, depending on the stage—as a standard aspect of managing esophageal cancer. Nonoperative therapy is usually reserved for patients who are not candidates for surgery because of clinical conditions or advanced disease. [10, 11, 12, 13]

Anatomy

The esophagus is a muscular tube that extends from the level of the 7th cervical vertebra to the 11th thoracic vertebra. The esophagus can be divided into the following anatomic parts:

-

Cervical esophagus

-

Thoracic esophagus

-

Abdominal esophagus

The blood supply of the cervical esophagus is derived from the inferior thyroid artery, while the blood supply for the thoracic esophagus comes from the bronchial arteries and the aorta. The abdominal esophagus is supplied by branches of the left gastric artery and inferior phrenic artery.

Venous drainage of the cervical esophagus is through the inferior thyroid vein, while the thoracic esophagus drains via the azygous vein, the hemiazygous vein, and the bronchial veins. The abdominal esophagus drains through the coronary vein.

The esophagus is characterized by a rich network of lymphatic channels in the submucosa that can facilitate the longitudinal spread of neoplastic cells along the esophageal wall. Lymphatic drainage is to the following node basins:

-

Cervical

-

Tracheobronchial

-

Mediastinal

-

Gastric

-

Celiac

Pathophysiology

Major risk factors for SCC include alcohol consumption and tobacco use. Most studies have shown that alcohol is the primary risk factor but smoking in combination with alcohol consumption can have a synergistic effect.

Alcohol damages the cellular DNA by decreasing metabolic activity within the cell and therefore inhibits detoxification and promotes oxidation. [14] Alcohol is a solvent, specifically of fat-soluble compounds. Therefore, the carcinogens within tobacco are able to penetrate the esophageal epithelium more easily.

Some of the carcinogens in tobacco include the following:

-

Aromatic amines

-

Nitrosamines

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

-

Aldehydes

-

Phenols

Other carcinogens, such as nitrosamines found in certain salted vegetables and preserved fish, have also been implicated in esophageal SCC. The pathogenesis appears to be linked to inflammation of the squamous epithelium that leads to dysplasia and in situ malignant transformation. [15]

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus most commonly occurs in the distal esophagus and has a distinct relationship to GERD. Untreated GERD can progress to Barrett esophagus (BE), in which the stratified squamous epithelium that normally lines the esophagus is replaced by a columnar epithelium.

The chronic reflux of gastric acid and bile at the gastroesophageal junction and the subsequent damage to the esophagus has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Barrett metaplasia. Diagnosis of Barrett esophagus can be confirmed by biopsies of the columnar mucosa during an upper endoscopy.

Barrett esophagus incidence increases with age. The disorder is uncommon in children. It is more common in men than women and more common in whites than in Asians or African Americans. [14]

The progression of Barrett metaplasia to adenocarcinoma is associated with several changes in gene structure, gene expression, and protein structure. [16, 17, 18] The oncosuppressor gene TP53 and various oncogenes, particularly erb-b2, have been studied as potential markers. Casson and colleagues identified mutations in the TP53 gene in patients with Barrett epithelium associated with adenocarcinoma. [19] In addition, alterations in p16 genes and cell cycle abnormalities or aneuploidy appear to be some of the most important and well-characterized molecular changes.

Obesity is another risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, specifically in individuals with central fat distribution. [20] Hypertrophied adipocytes and inflammatory cells within fat deposits create an environment of low-grade inflammation and promote tumor development through the release of adipokines and cytokines. Adipocytes in the tumor microenvironment supply energy production and support tumor growth and progression. [21]

Etiology

The etiology of esophageal carcinoma is thought to be related to exposure of the esophageal mucosa to noxious or toxic stimuli, resulting in a sequence of dysplasia to carcinoma in situ to carcinoma. In Western cultures, retrospective evidence has implicated cigarette smoking and chronic alcohol exposure as the most common etiologic factors for squamous cell carcinoma. High body mass index, GERD, and resultant Barrett esophagus are often the associated factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma. [22]

Certain factors can increase or decrease risk for both cancer types. A study by Steevens et al found that in current smokers, increased consumption of specific groups of vegetables and fruits were inversely associated with risk for esophageal SCC and adenocarcinoma. [23] Total vegetable consumption nonsignificantly reduced risk for both esophageal cancer types. Consumption of raw vegetables and of citrus fruits was inversely associated with risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma. The risk of both SCC and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus was increased in current smokers. [24]

Risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

The risk factors and etiologic associations for SCC of the esophagus include the following:

-

Smoking and alcohol use

-

Diet

-

Certain infections

-

Tylosis

Smoking and alcohol use

The Netherlands Cohort Study, a prospective study in 120,852 participants, demonstrated the combined effects of smoking and alcohol consumption on risk of SCC of the esophagus. [24] In participants who drank 30 g or more of ethanol daily, the multivariable adjusted incidence rate ratio (RR) for esophageal SCC was 4.61 compared with abstainers. The RR for current smokers who consumed more than 15 g/day of ethanol was 8.05 when compared with nonsmokers who consumed less than 5 g/day of ethanol.

No associations were found between alcohol consumption and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Dietary associations

Esophageal SCC has a wide variety of dietary associations, among them the following:

-

Foods products containing N-nitroso compounds increase the risk of esophageal SCC. [25]

-

Toxin-producing fungi (eg, aflatoxin) induce carcinogenesis by reducing nitrates to nitroso compounds. [26]

-

Areca nuts or betel quid (areca nuts wrapped in betel leaves) increase the risk through the release of copper, with resulting induction of collagen synthesis by fibroblasts [27]

-

Red meat consumption increases the risk [28]

-

Low dietary folate intake is associated with an increased risk of esophageal SCC. [34]

-

Higher intake of fruits and vegetables reduces the risk of esophageal SCC. [35]

A variety of other factors may promote esophageal SCC. These include the following:

-

Caustic stricture

-

Achalasia cardia

-

Prior gastrectomy

-

Use of oral bisphosphonates [36]

-

Drinking scalding-hot liquids (hotter than 65° C [149° F])

-

Poor oral hygiene

-

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

A Chinese study found that risk for esophageal cancer was five times higher in individuals who drank very hot tea and drank more than 15 g of alcohol every day compared with those who drank tea less than once a week and consumed fewer than 15 g of alcohol daily (hazard ratio [HR], 5.00). Risk was doubled in those who drank very hot tea daily and smoked tobacco, compared with nonsmokers who drank tea only occasionally (HR, 2.03). The analysis included 456,155 participants aged 30 to 79 years who did not have a prior history of cancer. [37, 38]

A genome-wide association study by Wu et al identified seven susceptibility loci on chromosomes 5q11, 6p21, 10q23, 12q24, and 21q22, suggesting the involvement of multiple genetic loci and gene-environment interaction in the development of esophageal SCC. [39]

Bisphosphonate use can result in esophagitis and has been suggested as a risk factor for esophageal carcinoma. However, a large study found no significant difference in the frequency of esophageal or gastric cancers between the bisphosphonate cohort and the control group. [40]

Infections

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection has been recognized as a contributing factor to esophageal cancer. However, Sitas et al reported limited serologic evidence of an association between esophageal SCC and HPV in a study of more than 4000 subjects. The study could not exclude the possibility that certain HPV types may be involved in a small subset of cancers, although HPV does not appear to be an important risk factor. [41] . Helicobacter pylori infection, which can cause stomach cancer, has not been associated with esophageal cancer.

Tylosis

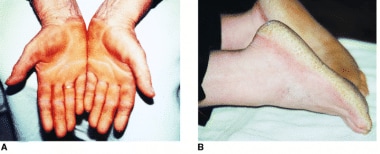

Tylosis is a rare autosomal dominant disease caused by a mutation in TEC (tylosis with esophageal cancer), a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 17q25. Tylosis is associated with hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles (see the images below) and a high rate of esophageal SCC (40% to 90% by the age of 70 years). [42] The inherited type of tylosis (Howell-Evans syndrome) has been most strongly linked to esophageal SCC. [43, 44] Surveillance by upper GI endoscopy is recommended for family members with tylosis after 20 years of age. [45]

Palmoplantar keratoderma (tylosis) of palms (A) and soles (B). Courtesy of The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Nature Publishing Group.

Palmoplantar keratoderma (tylosis) of palms (A) and soles (B). Courtesy of The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Nature Publishing Group.

Risk factors for adenocarcinoma

The principal risk factors and etiologic associations for esophageal adenocarcinoma include the following:

-

GERD

-

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

GERD is the most common predisposing factor for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Adenocarcinoma may represent the last event of a sequence that starts with irritation caused by the reflux of acid and bile and progresses to specialized intestinal (Barrett) metaplasia, low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and finally adenocarcinoma see the image below). Approximately 10%-15% of patients who undergo endoscopy for evaluation of GERD symptoms are found to have Barrett epithelium.

Esophageal cancer. Cascade of events that lead from gastroesophageal reflux disease to adenocarcinoma.

Esophageal cancer. Cascade of events that lead from gastroesophageal reflux disease to adenocarcinoma.

In 1952, Morson and Belcher published the first description of a patient with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus arising in a columnar epithelium with goblet cells. [46] In 1975, Naef et al emphasized the malignant potential of Barrett esophagus. [47]

The risk of adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett metaplasia has been estimated to be 30-60 times that of the general population. A nationwide population-based case-control study performed in Sweden found an odds ratio of 7.7 for adenocarcinoma in persons with recurrent symptoms of reflux, as compared with persons without such symptoms, and an odds ratio of 43.5 in patients with long-standing and severe symptoms of reflux. [22]

Although the annual risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma in people with GERD has been reported at 0.5%, some studies have found lower risk. Data from the Northern Ireland Barrett Esophagus Register, which is one of the largest population-based registries in the world, found that malignant progression in patients with Barrett esophagus was 0.22% per year. This suggests that current surveillance approaches may not be cost effective. [48]

A study by Hvid-Jensen et al examined a large Danish registry (11,028 patients over a median of 5.2 years) and found the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma to be 1.2 cases per 1000 person-years (or 0.12% annual risk). Low-grade dysplasia detected on index endoscopy was associated with an incidence rate of 5.1 cases per 1000 person-years, compared with 1 per 1000 person-years in those without dysplasia. [49]

Additional factors that increase the risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma, particularly in patients with Barrett esophagus, include cigarette smoking [50] and certain polymorphisms of the epidermal growth factor gene that have been associated with higher serum levels of epidermal growth factor. [51] Freedman et al suggested a possible association between cholecystectomy and esophageal adenocarcinoma, likely due to the toxic effect of refluxed duodenal juice containing bile on esophageal mucosa [52]

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

Obesity has been linked to a higher risk for Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. [53, 54] Individuals in the highest quartile for body mass index (BMI) have a 7.6-fold higher risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma compared with those in the lowest quartile. A meta-analysis of case control and cohort studies revealed a relative risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma of 1.71 (95% confidence index [CI] 1.5-1.96) for BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2, and 2.34 (95% CI 1.95-2.81) for BMI ≥30 kg/m2. [55] Obesity does not appear to increase the risk of esophageal SCC. [56]

Obesity increases the risk of GERD and subsequently of esophageal adenocarcinoma by a "mechanical" process that consists of an amplification of intragastric pressure, disruption of normal esophageal sphincter function, and increased risk of a hiatal hernia. [57] Obesity also has an inflammatory effect mediated by the release of various proinflammatory cytokines, which can lead to metabolic syndrome, a constellation of metabolic disorders that includes obesity, impaired fasting glucose, high blood pressure, and dyslipidemia. Like obesity, metabolic syndrome is also linked with the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. [58]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The American Cancer Society estimates that 22,070 new cases of esophageal cancer (17,430 in men and 4640 in women) will be diagnosed in the United States in 2025, and that 16,1250 persons (12,940 men and 3310 women) will die of the disease. [59] Esophageal cancer is the 17th most common cancer in the US, but the seventh most common cause of cancer death in males. [60, 59] The 5-year survival rate from 2014 to 2020 was 21.6%. [60]

The incidence of esophageal carcinoma is approximately 3-6 cases per 100,000 population, although certain endemic areas appear to have higher per-capita rates. The age-adjusted annual incidence was 4.2 per 100,000 men and women, based on 2017-2021 cases. [60]

The epidemiology of esophageal carcinoma has changed markedly over the past several decades in the United States. [61] Until the 1970s, squamous cell carcinoma was the most common type of esophageal cancer (90-95%). It was typically located in the thoracic esophagus and most frequently affected African-American men with a long history of smoking and alcohol consumption.

Subsequently, rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma rose markedly, particularliy in Whites. In White men, the incidence rate of esophageal adenocarcinoma exceeded that of squamous cell carcinoma around 1990, while in White women aged 45–59 years, adenocarcinoma overtook squamous cell carcinoma in 2006–2010. [62]

From 1973 to 1996, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma increased by 8.2% annually. From 1996 to 2006, the rate of increase fell to 1.3% annually, principally because of a plateau in the incidence of early-stage disease. Prior to 1996, early-stage cases increased by 10% annually; subsequently, they declined by 1.6% annually. [63] From 2004 to 2014, incidence rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma in the United States fell on average 1.4% each year. [60]

International statistics

Esophageal câncer is the 11th most common cancer and the 7th most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide. It is endemic in many parts of the world, particularly in the third world countries, where it is the fourth most common cause of cancer deaths. Incidence rates are variable worldwide, with the highest rates found in eastern Asia and southern and eastern Africa, and the lowest rates in western and northern Africa and Central America in both men and women. [4]

In some regions, such as areas of northern Iran, some areas of southern Russia, and northern China (sometimes called an "esophageal cancer belt"), the incidence of esophageal carcinoma may be as high as 800 cases per 100,000 population. Major risk factors in these areas are not well known but are probably related to the poor nutritional status, including low intake of fruits and vegetables and drinking very hot beverages. Unlike in the United States, squamous cell carcinoma is responsible for 95% of all esophageal cancers worldwide.

Sex- and age-related demographics

Esophageal cancer is more common in men than in women. Worldwide, esophageal cancer is 2 to 3 times more common in men; in the US, it is more than 4 times more common in men. [4, 60]

Esophageal cancer occurs most commonly during the sixth and seventh decades of life. The disease becomes more common with advancing age; it is about 20 times more common in persons older than 65 years than it is in individuals below that age. Median age at diagnosis is 68 years. [60]

Prognosis

Between 2014 and 2020, the overall 5-year survival rate for esophageal cancer was 21.6%. [60] However, survival in patients with esophageal cancer depends on the stage of the disease. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, stage-by-stage, appear to have equivalent survival rates.

Lymph node or solid organ metastases are associated with low survival rates. Patients without lymph node involvement have a significantly better prognosis and 5-year survival rate than patients with involved lymph nodes. Stage IV lesions with distant metastasis are associated with a 5-year survival rate of around 5%. (See the table below.)

Table 2. Five-year esophageal cancer survival rates by stage at diagnosis in the US, 2014-2020 [60] (Open Table in a new window)

Stage |

Survival Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Localized | 48.1 |

| Regional | 28.1 |

| Distant | 5.3 |

| All Stages | 21.6 |

The 5-year survival rate in 2015 was 21.5% in Whites and 13.5% in Blacks. [64]

A report of 1085 patients who underwent transhiatal esophagectomy for cancer showed that the operation was associated with a 4% operative mortality rate and a 23% 5-year survival rate. A better 5-year survival rate (48%) was identified in a subgroup of patients who had a complete response (ie, disappearance of the tumor) following preoperative radiation and chemotherapy (ie, neoadjuvant therapy). [65]

Transhiatal and transthoracic esophagectomies have equivalent long-term survival rates. [66, 67]

Imaging and prognosis

Suzuki et al found that a higher initial standardized uptake value on positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is associated with poorer overall survival in patients with esophageal or gastroesophageal carcinoma receiving chemoradiation. The authors suggested that PET scanning may become useful for individualizing therapy. [68]

A study by Gillies et al also found that PET–computed tomography (CT) scanning can be used to predict survival; in this study, the presence of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid lymph nodes was an independent adverse prognostic factor. [69]

HER-2 and prognosis

In some studies of esophageal cancer, human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER-2) positivity correlated with tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis, and portended a poor prognosis. [10, 70] For example, a study by Prins et al of HER-2 protein overexpression and HER-2 gene amplification in esophageal carcinomas found that HER-2 positivity and gene amplification are independently associated with poor survival. In their study, which involved 154 patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma, HER-2 positivity was seen in 12% of these patients and overexpression was seen in 14% of them. [71] Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend testing for HER2 and adding the HER2 monoclonal antibody to chemotherapy regimens when HER2 overexpression is found. [10]

-

Esophageal cancer. Endoscopy demonstrating intraluminal esophageal cancer.

-

Esophageal cancer. Cascade of events that lead from gastroesophageal reflux disease to adenocarcinoma.

-

Esophageal cancer. Barium swallow demonstrating stricture due to cancer.

-

Esophageal cancer. Barium swallow demonstrating an endoluminal mass in the mid esophagus.

-

Esophageal cancer. Chest CT scan showing invasion of the trachea by esophageal cancer.

-

Esophageal cancer. Transhiatal esophagectomy in which (a) is the abdominal incision, (b) is the cervical incision, and (c) is the stomach stretching from abdomen to the neck.

-

Esophageal cancer. Five-year survival for esophageal cancer based on TNM stage.

-

Esophageal cancer. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, high power, showing junction of benign glands in the lower right, Barrett columnar cell metaplasia with a large goblet cell containing blue mucin in the lower center, and adenocarcinoma on the left.

-

Esophageal cancer. Macroscopic image of a resection of the gastroesophageal junction. On the right is non-neoplastic esophagus, consisting of tan, smooth mucosa. On the left is the non-neoplastic rugal folds of the stomach. In the center of the picture is an ulcer with a yellow-green fibrinous exudate surrounded by irregular, heaped-up margins with almost a cobblestone appearance. The latter represents mucosal adenocarcinoma with probably some Barrett metaplasia in the background.

-

Esophageal cancer. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, high power, demonstrating invasive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. This carcinoma does not form glands and instead shows features of squamous differentiation, including keratinization and intercellular bridges.

-

Esophageal cancer. Macroscopic image of an esophageal resection. A polypoid squamous cell carcinoma is visible protruding from the esophageal mucosal surface (left center of specimen).

-

Esophageal cancer. On this positron emission computed tomography (PET) scan, esophageal cancer is evident as a golden lesion in the chest.

-

Palmoplantar keratoderma (tylosis) of palms (A) and soles (B). Courtesy of The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Nature Publishing Group.

-

Esophageal cancer. Diagram showing T1,T2 and T3 stages of esophageal cancer. Courtesy of Cancer Research UK and Wikimedia Commons.

-

Esophageal cancer. Micrograph of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (H&E stain). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

-

Esophageal cancer. Low-magnification micrograph of an intramucosal esophageal adenocarcinoma (H&E stain). Endoscopic mucosal resection specimen. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Antineoplastics, Antimetabolite

- Antineoplastics, Alkylating

- PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

- Antineoplastics, Antimicrotubular

- Antineoplastics, Anthracycline

- Antineoplastics, Topoisomerase Inhibitors

- Thymidine Analog

- Antineoplastics, Other

- Antineoplastics, Anti-HER2

- Antineoplastics, VEGF Inhibitors

- Anti-Claudin Monoclonal Antibodies

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References