Practice Essentials

Insomnia is characterized by persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, maintenance, or quality despite adequate opportunity for sleep. Symptoms may present as nighttime sleep disturbances and/or daytime impairments.

Signs and symptoms

Nighttime symptoms include:

-

Difficulty falling asleep (taking longer than 30 min to initiate sleep)

-

Frequent nocturnal awakenings (difficulty staying asleep)

-

Early morning awakening with an inability to return to sleep

-

Nonrestorative or poor-quality sleep, despite sufficient time in bed

Daytime symptoms include:

-

Fatigue or low energy

-

Daytime sleepiness (less common in primary insomnia, but may occur with comorbid conditions)

-

Impaired concentration, memory, or decision-making

-

Mood disturbances (irritability, anxiety, or depression)

-

Decreased performance at work or school

-

Increased risk of errors or accidents (eg, motor vehicle crashes, workplace incidents)

Acute insomnia (lasting < 1 month) is often triggered by situational stressors(eg, illness, work stress, bereavement).

Chronic insomnia (lasting ≥ 3 months and occurring ≥ 3 nights per week) is associated with underlying medical, psychiatric, or behavioral factors.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Insomnia is a clinical diagnosis. Diagnostic studies are indicated principally for the clarification of comorbid disorders. Measures that may be considered include the following:

-

Studies for hypoxemia

-

Polysomnography and daytime multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT)

-

Actigraphy

-

Sleep diary

-

Genetic testing (eg, for fatal familial insomnia [FFI])

-

Brain imaging (eg, to assist in the diagnosis of FFI [1] )

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is considered the most appropriate treatment for patients with primary insomnia, though it is also effective for comorbid insomnia as adjunctive therapy. [2]

Components of CBT-I include:

-

Sleep hygiene education

-

Cognitive restructuring to reduce sleep-related anxiety

-

Stimulus control therapy

-

Sleep restriction therapy

-

Relaxation techniques

Pharmacologic treatment may be considered when CBT-I alone is insufficient.

-

First-line medications: Nonbenzodiazepine receptor agonists (eg, eszopiclone, zolpidem, zaleplon), ramelteon, or orexin receptor antagonists (eg, daridorexant, lemborexant, suvorexant)

-

Adjunctive options: Sedating antidepressants (eg, trazodone, mirtazapine), low-dose doxepin, and melatonin agonists

-

Benzodiazepines should be used cautiously and avoided in elderly patients, pregnant women, and individuals with sleep apnea

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Insomnia is defined as repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, maintenance, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate time and opportunity for sleep and that results in some form of daytime impairment. [3] Specific criteria vary, but common ones include taking longer than 30 minutes to fall asleep, staying asleep for less than 6 hours, waking more than 3 times a night, or experiencing sleep that is chronically nonrestorative or poor in quality. [4]

Diagnostic criteria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) makes no distinction between primary and comorbid insomnia. This previous distinction had been of questionable relevance in clinical practice and a diagnosis of insomnia is made if an individual meets the diagnostic criteria, despite any coexisting conditions.

The DSM-5-TR defines insomnia as dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, associated with one (or more) of the following symptoms: [5]

-

Difficulty initiating sleep

-

Difficulty maintaining sleep, characterized by frequent awakenings or problems returning to sleep after awakenings

-

Early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep

Other criteria include the following:

-

The sleep disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairments in social, occupational, educational, academic, behavioral, or other important areas of functioning

-

The sleep difficulty occurs at least 3 nights per week

-

The sleep difficulty is present for at least 3 months

-

The sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep

-

The insomnia cannot be explained by and does not occur exclusively during the course of another sleep-wake disorder

-

The insomnia is not attributable to the physiological effects of a drug of abuse or medication.

-

Coexisting mental disorders and medical conditions do not adequately explain the predominant complaint of insomnia

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition, Text Revision (ICSD-3-TR) [3] has streamlined the classification of insomnia disorders. Unlike earlier editions that delineated multiple subtypes, the ICSD-3-TR now primarily recognizes Chronic Insomnia Disorder and Short-Term Insomnia Disorder.

Acute and chronic insomnia

Insomnia is usually a transient or short-term condition. In some cases, however, insomnia can become chronic.

Acute insomnia lasts up to 1 month. It is often referred to as adjustment insomnia because it most often occurs in the context of an acute situational stress, such as a new job or an upcoming deadline or examination. This insomnia typically resolves when the stressor is no longer present or the individual adapts to the stressor.

However, transient insomnia often recurs when new or similar stresses arise in the patient’s life. [3] Transient insomnia lasts for less than 1 week and can be caused by another disorder, changes in the sleep environment, stress, or severe depression.

Chronic insomnia lasting more than 1 month can be associated with a wide variety of medical and psychiatric conditions and typically involves conditioned sleep difficulty. However, it is believed to occur primarily in patients with an underlying predisposition to insomnia.

Chronic insomnia has numerous health consequences (see Prognosis). For example, patients with insomnia demonstrate slower responses to challenging reaction-time tasks. [6] Moreover, patients with chronic insomnia report reduced quality of life, comparable to that experienced by patients with such conditions as diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease. Quality of life improves with treatment but still does not reach the level seen in the general population. [7]

In addition, chronic insomnia is associated with impaired occupational and social performance and an absenteeism rate that is 10-fold greater than controls. Furthermore, insomnia is associated with higher health care use, including a 2-fold higher frequency of hospitalizations and office visits. In primary care medicine, approximately 30% of patients report significant sleep disturbances.

Epidemiology

Studies indicate that approximately 12% of Americans have been diagnosed with chronic insomnia. Globally, about 10% of adults suffer from insomnia disorders, with an additional 20% experiencing occasional insomnia symptoms. Women, older adults, and individuals facing socioeconomic challenges are more susceptible to developing insomnia. [8, 9]

Insomnia often follows a chronic course, with studies showing a 40% persistence rate over a five-year period. Each year, approximately 25% of Americans experience acute insomnia; however, about 75% of these cases resolve without progressing to chronic insomnia.

The prevalence of insomnia varies across regions. In Europe, data indicates that between 5.5% and 6.7% of adults experience chronic insomnia. [10] In the Americas (Northern America, Latin America, and the Caribbean) an estimated 16.8% (123 million) of adults are affected. [11]

Anatomy

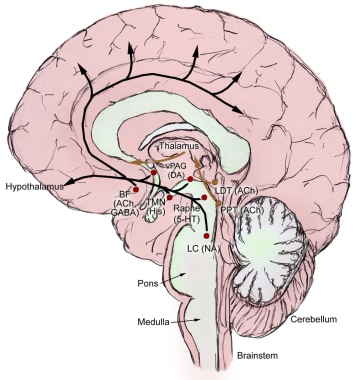

Sleep and wakefulness is a tightly regulated process. Reciprocal connections in the brain produce consolidated periods of wakefulness and sleep that are entrained by environmental light to occur at specific times of the 24-hour cycle.

Promotion of wakefulness

Brain areas critical for wakefulness consist of several discrete neuronal groups centered around the pontine and medullary reticular formation and its extension into the hypothalamus (see the image below). Although diverse in terms of neurochemistry, these cell groups share the features of a diffuse “ascending” projection to the forebrain and a “descending” projection to brainstem areas involved in regulating sleep-wake states. The neurotransmitters involved, along with the main cell groups that produce them, are as follows:

Histamine – histaminergic cells in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) in the posterior hypothalamus

-

Norepinephrine – norepinephrine-producing neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC)

-

Serotonin – serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN)

-

Dopamine – dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA)

Each region and neurotransmitter contributes to the promotion of wakefulness, but chronic lesions of any one system do not disrupt wakefulness. This suggests a redundant system, wherein the absence of one neurotransmitter may be compensated by the other systems.

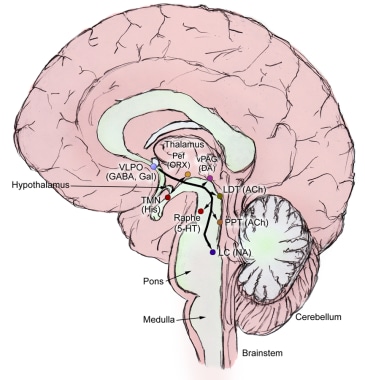

Promotion of sleep

The anterior hypothalamus includes the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO), containing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and the peptide galanin, which are inhibitory and promote sleep (see the image below). These project to the TMN and the brainstem arousal regions to inhibit wakefulness.

Ventrolateral pre-optic nucleus inhibitory projections to main components of the arousal system to promote sleep.

Ventrolateral pre-optic nucleus inhibitory projections to main components of the arousal system to promote sleep.

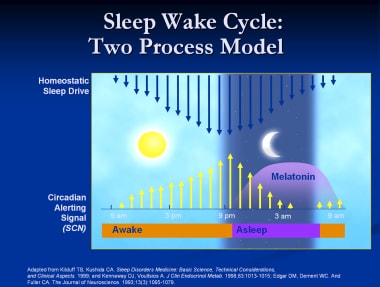

The homeostatic and circadian processes

Both animal and human studies support a model of two processes that regulate sleep and wakefulness: homeostatic and circadian. The homeostatic process is the drive to sleep that is influenced by the duration of wakefulness. The circadian process transmits stimulatory signals to arousal networks to promote wakefulness in opposition to the homeostatic drive to sleep. (See the image below.)

Melatonin and the circadian process

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is entrained to the external environment by the cycle of light and darkness. The retinal ganglion cells transmit light signals via the retinohypothalamic tract to stimulate the SCN. A multisynaptic pathway from the SCN projects to the pineal gland, which produces melatonin.

Melatonin synthesis is inhibited by light and stimulated by darkness. The nocturnal rise in melatonin begins between 8 and 10 pm and peaks between 2 and 4 am, then declines gradually over the morning. [12] Melatonin acts via two specific melatonin receptors: MT1 attenuates the alerting signal, and MT2 phase shifts the SCN clock. The novel sleep-promoting drug ramelteon acts specifically at the MT1 and MT2 receptors to promote sleep but is structurally unrelated to melatonin. It has a relatively a short half-life (2.6 hours).

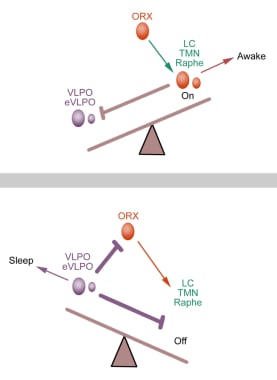

The flip-flop switch model

Saper et al proposed the flip-flop switch model of sleep-wake regulation. [13] This flip-flop circuit consists of two sets of mutually inhibitory components. The sleep side is the VLPO, and the arousal side includes TMN histaminergic neurons and brainstem arousal regions (the DRN serotonergic neurons, VTA dopaminergic neurons, and LC noradrenergic neurons).

Each side of the switch inhibits the other. For example, when activation of one side is slightly stronger, the weaker side has increased inhibition, thus further tipping the balance toward the stronger side. This flip-flop switch allows for rapid state transitions. (See the schematic flip-flop switch model in the image below.)

Schematic flip-flop switch model. Adapted from Saper C et al. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature 2005;437:1257-1263.

Schematic flip-flop switch model. Adapted from Saper C et al. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature 2005;437:1257-1263.

Hypocretin neurons in the posterolateral hypothalamus are active during wakefulness and project to all of the wakefulness arousal systems described above. Hypocretin neurons interact with both the sleep-active and the sleep-promoting systems and act as stabilizers between wakefulness-maintaining and sleep-promoting systems to prevent sudden and inappropriate transitions between the two systems. [14]

Narcolepsy with cataplexy illustrates the disruption of this system. These patients have a greater than 90% loss of hypocretin neurons, and they have sleep-wake state instability with bouts of sleep intruding into wakefulness. [15]

Pathophysiology

Insomnia usually results from an interaction of biological, physical, psychological, and environmental factors. Although transient insomnia can occur in any person, chronic insomnia appears to develop only in a subset of persons who may have an underlying predisposition to insomnia. [19] The evidence supporting this theory is that compared with persons who have normal sleep, persons with insomnia have the following: [20]

-

Higher rates of depression and anxiety

-

Higher scores on scales of arousal

-

Longer daytime sleep latency

-

Increased 24-hour metabolic rates [21]

-

Greater night-to-night variability in their sleep

-

More electroencephalographic (EEG) beta activity (a pattern observed during memory processing/performing tasks) at sleep onset

-

Increased global glucose consumption during the transition from waking to sleep onset, on positron emission tomography of the brain

Hyperarousal

In experimental models of insomnia, healthy subjects deprived of sleep do not demonstrate the same abnormalities in metabolism, daytime sleepiness, and personality as subjects with insomnia. However, in an experimental model in which healthy individuals were given caffeine, causing a state of hyperarousal, the healthy subjects had changes in metabolism, daytime sleepiness, and personality similar to the subjects with insomnia. [22]

Clinical research has also shown that patients with chronic insomnia show evidence of increased brain arousal. For example, studies have indicated that patients with chronic primary insomnia demonstrate increased fast-frequency activity during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, which is an EEG sign of hyperarousal, and evidence of reduced deactivation in key sleep/wake regions during NREM sleep compared with controls.

Furthermore, patients with insomnia have higher day and night body temperatures, urinary cortisol and adrenaline secretion, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels than patients with normal sleep. [23, 24] These results support a theory that insomnia is a manifestation of hyperarousal. In other words, the poor sleep itself may not be the cause of the daytime dysfunction, but merely the nocturnal manifestation of a general disorder of hyperarousability.

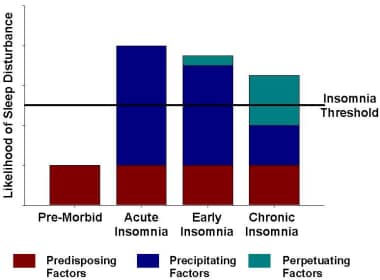

Spielman model

The Spielman model (see the image below) of chronic insomnia posits three components: predisposing factors, precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors. [25] According to this model, predisposing factors may cause the occasional night of poor sleep, but in general, the person sleeps well until a precipitating event (eg, death of a loved one) occurs, which triggers acute insomnia. If bad sleep habits develop or other perpetuating factors set in, the insomnia becomes chronic and will persist even with removal of the precipitating factor.

Theoretical model of the factors causing chronic insomnia. Chronic insomnia is believed to primarily occur in patients with predisposing or constitutional factors. These factors may cause the occasional night of poor sleep but not chronic insomnia. A precipitating factor, such as a major life event, causes the patient to have acute insomnia. If poor sleep habits or other perpetuating factors occur in the following weeks to months, chronic insomnia develops despite the removal of the precipitating factor. Adapted from Spielman AJ, Caruso LS, Glovinsky PB: A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1987 Dec;10(4):541-53.

Theoretical model of the factors causing chronic insomnia. Chronic insomnia is believed to primarily occur in patients with predisposing or constitutional factors. These factors may cause the occasional night of poor sleep but not chronic insomnia. A precipitating factor, such as a major life event, causes the patient to have acute insomnia. If poor sleep habits or other perpetuating factors occur in the following weeks to months, chronic insomnia develops despite the removal of the precipitating factor. Adapted from Spielman AJ, Caruso LS, Glovinsky PB: A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1987 Dec;10(4):541-53.

Genetics

A number of individual genes that are involved in sleep and wakefulness have been isolated. However, current evidence suggests that a network of genes, rather than a single gene or a subset of genes, is responsible for sleep. The neurotransmitters and signaling pathways that serve wakefulness also serve other functions. [26]

Studies indicate differential genetic susceptibility to exogenous influences such as caffeine, light, and stress. For example, one study found that differences in the adenosine 2A receptor gene (ADORA2) determine differential sensitivity to caffeine’s effect on sleep. [27] The ADORA2A 1083T>C genotype determined how closely the caffeine-induced changes in brain electrical activity (ie, increased beta activity) during sleep resembled the alterations observed in patients with insomnia.

In addition, circadian clock genes have been identified that regulate the circadian rhythm. [28] Such genes include CLOCK and Per2. A mutation or functional polymorphism in Per2 can lead to circadian rhythm disorders, such as advanced sleep phase syndrome (sleep and morning awakening occur earlier than normal) and delayed sleep phase syndrome (sleep and morning awakening are delayed).

A missense mutation has been found in the gene encoding the GABAA beta 3 subunit in a patient with chronic insomnia. [29] Polymorphisms in the serotonin receptor transporter gene may modulate the ability of an individual to handle stress or may confer susceptibility to depression. In depression, serotonin is an important neurotransmitter for arousal mechanisms. Furthermore, antagonism of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptor promotes slow-wave sleep.

Fatal familial insomnia

A rare condition, fatal familial insomnia (FFI, previously known as thalamic dementia) is an autosomal dominant human prion disease caused by changes in the PRNP (prion protein) gene. FFI involves a severe disruption of the physiologic sleep pattern that progresses to hallucinations, a rise in catecholamine levels, autonomic disturbances (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis), and significant cognitive and motor deficits. Mean age of onset is 50 years, and average survival is 18 months. [30, 31, 32]

FFI and a subtype of familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) share the same mutation at codon 178 (Asn178) in the PRNP gene. They differ in that a methionine-valine polymorphism is present at codon 129 in PRNP in this subtype of familial CJD. [33]

Sporadic fatal insomnia (SFI) shares a similar clinic course with FFI but does not appear to be inherited. A mutation at codon 178 of the PRNP gene is not found in these patients, but patients have been found to be homozygous for methionine at codon 129 in PRNP. [34]

Precipitating factors

In retrospective studies, a large proportion of patients with insomnia (78%) can identify a precipitating trigger for their insomnia. Morin and colleagues showed that these patients demonstrate an increased response to stress as compared with controls. A number of factors can trigger insomnia in vulnerable individuals, including depression, anxiety, sleep-wake schedule changes, medications, other sleep disorders, and medical conditions. [35] In addition, positive or negative family events, work-related events, and health events are common insomnia precipitants.

Perpetuating factors

Regardless of how insomnia was triggered, cognitive and behavioral mechanisms are generally accepted to be the factors that perpetuate it. Cognitive mechanisms include misconceptions about normal sleep requirements and excessive worry about the ramifications of the daytime effects of inadequate sleep. Conditioned environmental cues causing insomnia develop from the continued association of sleeplessness with situations and behaviors that are typically related to sleep.

As a result, patients often become obsessive about their sleep or try too hard to fall asleep. These dysfunctional beliefs often produce sleep disruptive behaviors, such as trying to catch up on lost sleep with daytime naps or sleeping in, which in turn reduces the patients’ natural homeostatic drive to sleep at their habitual bedtime. Learned sleep-preventing associations are characterized by overconcern about inability to fall asleep.

Consequently, these patients develop conditioned arousal to stimuli that would normally be associated with sleep (ie, heightened anxiety and ruminations about going to sleep in their bedroom). A cycle then develops in which the more these patients strive to sleep, the more agitated they become, and the less they are able to fall asleep. They also have ruminative thoughts or clock watching as they are trying to fall asleep in their bedroom.

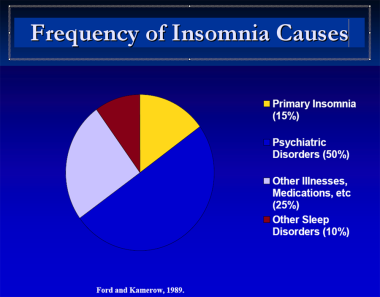

Etiology

Many clinicians assume that insomnia is often secondary to a psychiatric disorder, However, a large epidemiologic survey showed that half of insomnia diagnoses were not related to a primary psychiatric disorder. [36] A diagnosis of insomnia does, however, increase the future risk for depression or anxiety. Insomnia may also be secondary to other disorders or conditions, or it may be a primary condition (see the image below).

Adjustment insomnia (acute insomnia)

Adjustment insomnia is also known as transient, short-term, or acute insomnia. Causes can be divided into two broad categories: environmental and stress-related. Environmental etiologies include unfamiliarity, excessive noise or light, extremes of temperature, or an uncomfortable bed or mattress. Stress-related etiologies primarily involve life events, such as a new job or school, deadlines or examinations, or deaths of relatives and close friends.

Adjustment insomnia typically lasts 3 months or less. The insomnia resolves when the stressor is no longer present or the individual adapts to the stressor.

Psychophysiologic insomnia (primary insomnia)

Primary insomnia begins with a prolonged period of stress in a person with previously adequate sleep. The patient responds to stress with somatized tension and agitation.

In a person experiencing normal sleep, as the initial stress abates, the bad sleep habits are gradually extinguished because they are not reinforced nightly. However, in a patient with a tendency toward occasional poor nights of sleep, the bad habits are reinforced, the patient "learns" to worry about his or her sleep, and chronic insomnia follows.

The patient will have evidence of conditioned sleep difficulty and or/heightened arousal in bed, as indicated by one or more of the following:

-

Excessive focus on and heightened anxiety about sleep

-

Difficulty falling asleep at the desired bedtime or during planned naps, but no difficulty falling asleep during other monotonous activities when not intending to sleep

-

Ability to sleep better away from home than at home

-

Mental arousal in bed characterized by either intrusive thoughts or a perceived inability to volitionally cease sleep-preventing mental activity

-

Heightened somatic tension in bed reflected by a perceived inability to relax the body sufficiently to allow the onset of sleep

The sleep disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, medication use, or substance abuse disorder.

Paradoxical insomnia

In paradoxical insomnia, one or more of the following criteria apply:

-

The patient reports a chronic pattern of little or no sleep most nights, with rare nights during which relatively normal amounts of sleep are obtained

-

Sleep log data from one or more weeks of monitoring often show no sleep at all for several nights each week; typically, daytime naps are absent following such nights

-

There is typically a mismatch between objective findings from polysomnography or actigraphy and subjective sleep estimates from a self-reported sleep diary

At least one of the following is observed:

-

The patient reports constant or near-constant awareness of environmental stimuli throughout most nights

-

The patient reports a pattern of conscious thoughts or rumination throughout most nights while maintaining a recumbent posture

The daytime impairment reported is consistent with that reported by other insomnia subtypes but is much less severe than expected given the extreme level of sleep deprivation reported. The sleep disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, medication use, or substance-abuse disorder.

Insomnia due to medical condition

In patients with insomnia associated with a medical condition, medical disorders may include the following:

-

Chronic pain syndromes from any cause (eg, arthritis, cancer)

-

Advanced chronic obstructive lung disease

-

Benign prostatic hypertrophy (because of nocturia)

-

Chronic renal disease (especially if on hemodialysis)

-

Chronic fatigue syndrome

-

Fibromyalgia

-

Neurologic disorders

Neurologic disorders may include Parkinson disease, other movement disorders, and headache syndromes, particularly cluster headaches, which may be triggered by sleep.

In a retrospective community-based study, more people with chronic insomnia reported having the following medical conditions than did people without insomnia: [37]

-

Heart disease (21.9% with chronic insomnia vs 9.5% without insomnia)

-

High blood pressure (43.1% vs 18.7%)

-

Neurologic disease (7.3% vs 1.2%)

-

Breathing problems (24.8% vs 5.7%)

-

Urinary problems (19.7% vs 9.5%)

-

Chronic pain (50.4% vs 18.2%)

-

Gastrointestinal problems (33.6% vs 9.2%)

In addition, people with the following medical problems more often reported chronic insomnia than did patients without such medical problems: [37]

-

Heart disease (44.1% vs 22.8%)

-

Cancer (41.4% vs 24.6%)

-

High blood pressure (44% vs 19.3%)

-

Neurologic disease (66.7% vs 24.3%)

-

Breathing problems (59.6% vs 21.4%)

-

Urinary problems (41.5% vs 23.3%)

-

Chronic pain (48.6% vs 17.2%)

-

Gastrointestinal problems (55.4% vs 20.0%)

The sleep disturbance cannot be better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, medication use, or substance abuse disorder.

Insomnia due to mental disorders

Most chronic psychiatric disorders are associated with sleep disturbances. Depression is most commonly associated with early morning awakenings and an inability to fall back asleep. Conversely, studies have also demonstrated that insomnia can lead to depression: insomnia of more than 1-year duration is associated with an increased risk of depression.

Schizophrenia and the manic phase of bipolar illness are frequently associated with sleep-onset insomnia. Anxiety disorders (including nocturnal panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder) are associated with both sleep-onset and sleep-maintenance complaints.

To meet the formal definition of this form of insomnia, a mental disorder must be diagnosed according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). [5] The insomnia must be temporally associated with the mental disorder; however, in some cases, insomnia may appear a few days or weeks before the emergence of the underlying mental disorder.

The insomnia is more prominent than that typically associated with the mental disorders, as indicated by causing marked distress or constituting an independent focus of treatment. The sleep disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, medication use, or substance-abuse disorder.

Insomnia due to drug/substance abuse

Sleep disruption is common with the excessive use of stimulants, alcohol, or sedative-hypnotics. One of the following applies:

-

The patient has current, ongoing dependence on or abuse of a drug or substance known to have sleep-disruptive properties either during periods of use or intoxication or during periods of withdrawal

-

The patient has current ongoing use of or exposure to a medication, food, or toxin known to have sleep-disruptive properties in susceptible individuals

The insomnia is temporally associated with the substance exposure, use, or abuse, or acute withdrawal. The sleep disturbance cannot be better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, medication use, or substance abuse disorder.

Insomnia not due to substance or known physiologic condition, unspecified

This diagnosis is used for forms of insomnia that cannot be classified elsewhere in ICSD-2 but are suspected to be the result of an underlying mental disorder, psychological factors, or sleep disruptive processes. This diagnosis can be used on a temporary basis until further information is obtained to determine the specific mental condition or psychological or behavioral factors responsible for the sleep difficulty.

Inadequate sleep hygiene

Inadequate sleep hygiene practices are evident by the presence of at least one of the following:

-

Improper sleep scheduling consisting of frequent daytime napping, selecting highly variable bed or rising times, or spending excessive amounts of time in bed

-

Routine use of products containing alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine, especially in the period preceding bedtime

-

Engagement in mentally stimulating, physically activating, or emotionally upsetting activities too close to bedtime

-

Frequent use of the bed for activities other than sleep (eg, television watching, reading, studying, snacking, thinking, planning)

-

Failure to maintain a comfortable sleeping environment

The sleep disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, medication use, or substance abuse disorder.

Idiopathic insomnia

This sleep disturbance is a long-standing complaint of insomnia, with insidious onset in infancy or childhood. No precipitant or cause is identifiable. The course is persistent, with no sustained periods of remission. This condition is present in 0.7% of adolescents and 1% of very young adults. [38]

Behavioral insomnia of childhood

A child's symptoms meet the criteria for insomnia based on parents’ or other adult caregivers’ observations. Two types of this sleep disturbance are recognized: sleep-onset association and limit-setting.

The sleep-onset association type is characterized by the following:

-

Falling asleep is an extended process that requires special conditions

-

Sleep-onset associations are highly problematic or demanding

-

In the absence of associated conditions, sleep onset is significantly delayed or sleep is otherwise disrupted

-

Nighttime awakenings require caregiver intervention for the child to return to sleep

The limit-setting type is characterized by the following:

-

The child has difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep

-

The child stalls or refuses to go to bed at an appropriate time or refuses to return to bed following a nighttime awakening

-

The caregiver demonstrates insufficient or inappropriate limit-setting to establish appropriate sleeping behavior in the child

Primary sleep disorders causing insomnia

Included in this category are the following:

Restless legs syndrome

RLS is a sleep disorder characterized by the following:

-

An urge to move the legs, usually accompanied by uncomfortable and unpleasant physical sensations in the legs

-

Symptoms begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity such as lying or sitting

-

Symptoms are partially or totally relieved by moving, such as walking or stretching, at least as long as the activity continues

-

Symptoms are worse or occur only in the evening or at night

RLS may be associated with periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), which is characterized by repetitive periodic leg movements that occur during sleep. If RLS is predominant, sleep-onset insomnia is generally present; if PLMD is predominant, sleep-maintenance insomnia is more likely.

Obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome

A minority of patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome complain of insomnia rather than hypersomnolence. Often, these patients complain of multiple awakenings or sleep-maintenance difficulties. They may also have frequent nocturnal awakenings because of nocturia.

Circadian rhythm disorders

Circadian rhythm disorders include the following:

-

Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder

-

Advanced sleep-wake phase disorder

-

Irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder

-

Non-24-hour sleep-wake rhythm disorder

-

Shift work disorder

-

Jet lag disorder

-

Circadian sleep-wake disorder not otherwise specified

In advanced sleep phase syndrome, patients feel sleepy earlier than their desired bedtime (eg, 8 pm) and they wake up earlier than they would like (eg, 4-5 am). This condition is more common in the elderly (see Geriatric Sleep Disorder). These patients typically complain of sleep-maintenance insomnia.

In delayed sleep phase syndrome, patients do not feel sleepy until much later than the desired bedtime, and they wake up later than desired or socially acceptable. On sleep diaries or actigraphy, these patients show a consistent sleep time with earlier wake times that correspond to school or work days and delayed wake times on weekends, time off, and vacations.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome often begins in adolescence and may be associated with a family history in up to 40% of patients. These patients report difficulty falling asleep at usually socially desired bedtimes and complain of excessive daytime sleepiness during school or work.

Shift-work sleep disorder is a complaint of insomnia or excessive sleepiness that typically is temporally related to a recurring work schedule that overlaps with the usual sleep time. This can occur with early morning shifts (eg, starting at 4-6 am), where patients are anxious about waking up in time for their early shift, particularly when they have a rotating-shift schedule. Evening shifts that end at 11 pm can result in insomnia because the patient may need some time to wind down from work before retiring to bed.

Night shift work can be associated with both sleep-onset and sleep-maintenance insomnia. Triggers may include exposure to sunlight on the drive home from work, daylight exposure in the bedroom, and social and environmental cues (eg, picking up children at school, paying bills, household chores).

Irregular sleep-wake rhythm is typically seen in persons with poor sleep hygiene, particularly those who live or work alone with minimal exposure to light, activity, and social cues. It may also be seen in persons with dementia or some other neurodegenerative disorder. These patients randomly nap throughout the day, making it difficult, if not impossible, to fall asleep at a habitual bedtime with a consolidated sleep period.

Prognosis

Treatment of insomnia can improve these patients’ perceived health, function, and quality of life. [39] Consequences of untreated insomnia may include the following:

-

Impaired ability to concentrate, poor memory, difficulty coping with minor irritations, and decreased ability to enjoy family and social relationships

-

Reduced quality of life, often preceding or associated with depression and/or anxiety

-

More than 2-fold increase in the risk of having a fatigue-related motor vehicle accident

-

Apparent increase in mortality for individuals who sleep fewer than 5 hours each night

A prospective cohort study in ethnic Chinese in Taiwan demonstrated that sleep duration and insomnia severity were associated with all-cause death and cardiovascular disease events. [40] Other studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the cardiovascular consequences of insomnia. A 6-year prospective cohort study did not find an association between the development of hypertension and insomnia. [41] Other studies, however, indicate an association between short sleep or sleep restriction and hypertension. [42, 43]

A study of persons with insomnia and short sleep duration demonstrated an increased risk of hypertension to a degree comparable to that seen with sleep-disordered breathing. [44] A case-control study in normotensive subjects with chronic insomnia showed a higher nighttime systolic blood pressure and blunted day-to-night blood pressure dipping. [45]

Knutson et al found that the quantity and quality of sleep correlate with future blood pressure. In an ancillary study to the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) cohort study, measurement of sleep for 3 consecutive days in 578 subjects showed that shorter sleep duration and lower sleep maintenance predicted both significantly higher blood pressure levels and adverse changes in blood pressure over the next 5 years. [46]

Patients with insomnia report decreased quality of life compared with normal controls in all dimensions of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). Patients with insomnia report excessive fatigue as measured by the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Profiles of Mood Status (POMS).

Associations of insomnia with depression and anxiety

Insomnia is known to be associated with depression and anxiety. [36] What remains unknown is the nature of the association. For example, insomnia may presage the development of an incipient mood disorder, or mood disorders may independently predispose to insomnia.

In an early study of the association between insomnia and depression and anxiety, Ford and Kamerow found that after adjusting for medical disorders, ethnicity, and sex, patients with insomnia were 9.8 times more likely to have clinically significant depression and 17.3 times more likely to have clinically significant anxiety than persons without insomnia. [36] A meta-analysis by Baglioni et al concluded that in nondepressed people with insomnia, the risk of developing depression is twice as high as in people without sleep difficulties. [47]

Ohayon and Roth found that symptoms of insomnia were reported to occur before the first episode of an anxiety disorder 18% of the time; simultaneously 39% of the time; and after the onset of an anxiety disorder 44% of the time. [48] In addition, insomnia symptoms were reported to occur before the first episode of a mood disorder 41% of the time; simultaneously 29% of the time; and after the onset of a mood disorder 29% of the time.

Patient Education

All patients with insomnia, whether transient or chronic, should be educated about sleep and the elements of good sleep hygiene. Sleep hygiene refers to daily activities and habits that are consistent with or promote the maintenance of good quality sleep and full daytime alertness.

Educate patients on the following elements of good sleep hygiene:

-

Develop regular sleep habits; this means keeping a regular sleep and wake time, sleeping as much as needed to feel refreshed the following day, but not spending more time in bed than needed

-

Avoid staying in bed in the morning to catch up on sleep

-

Avoid daytime naps; if a nap is necessary, keep it short (less than 1 hour) and avoid napping after 3 pm

-

Keep a regular daytime schedule; regular times for meals, medications, chores, and other activities helps keep the inner body clock running smoothly

-

Do not read, write, eat, watch TV, talk on the phone, or play cards in bed

-

Avoid caffeine after lunch; avoid alcohol within 6 hours of bedtime; avoid nicotine before bedtime

-

Do not go to bed hungry, but do not eat a big meal near bedtime either

-

Avoid sleeping pills, particularly over-the-counter remedies

-

Slow down and unwind before bed (beginning at least 30 minutes before bedtime (a light snack may be helpful); create a bedtime ritual such as getting ready for bed, wearing night clothes, listening to relaxing music, or reading a magazine, newspaper, or book

-

Avoid watching TV in the bedroom or sleeping on the sofa and then going to bed later in the night

-

Avoid stimulating activities prior to bedtime (eg, vigorous exercise, discussing or reviewing finances, or discussing stressful issues with a spouse or partner or ruminating about them with oneself)

-

Keep the bedroom dark, quiet, and at a comfortable temperature

-

Exercise daily; this is best performed in the late afternoon or early evening (but not later than 6-7 pm)

-

Do not force yourself to sleep; if you are unable to fall asleep within 15-30 minutes, get up and do something relaxing until sleepy (eg, read a book in a dimly lit room, watch a non-stimulating TV program); avoid watching the clock or worrying about the perceived consequences of not getting enough sleep

-

Theoretical model of the factors causing chronic insomnia. Chronic insomnia is believed to primarily occur in patients with predisposing or constitutional factors. These factors may cause the occasional night of poor sleep but not chronic insomnia. A precipitating factor, such as a major life event, causes the patient to have acute insomnia. If poor sleep habits or other perpetuating factors occur in the following weeks to months, chronic insomnia develops despite the removal of the precipitating factor. Adapted from Spielman AJ, Caruso LS, Glovinsky PB: A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1987 Dec;10(4):541-53.

-

Mallampati airway scoring.

-

Diagnostic algorithm for major depression.

-

Diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder.

-

Sleep diary.

-

GABAA receptor subunit function(s).

-

GABAA receptor complex subunits and schematic representation of agonist binding sites.

-

Sleep-wake cycle.

-

The ascending arousal system. Adapted from Saper et al. Hypothalamic Regulation of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms. Nature 2005;437:1257-1263.

-

Ventrolateral pre-optic nucleus inhibitory projections to main components of the arousal system to promote sleep.

-

Schematic flip-flop switch model. Adapted from Saper C et al. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature 2005;437:1257-1263.

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

-

Frequency of insomnia causes.