Practice Essentials

Head injury can be defined as any alteration in mental or physical functioning related to a blow to the head (see the image below). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were approximately 214,110 TBI-related hospitalizations in the United States in 2020. In 2021, there were 59,473 TBI-related deaths. [1]

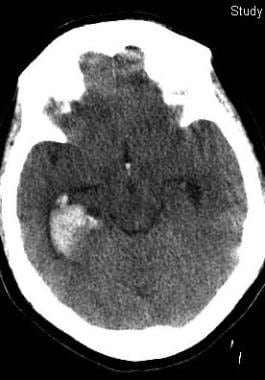

This 50-year-old woman with epilepsy seized and struck her head. Her initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 12. Her scan shows prominent right temporal bleeding. She recovered to baseline without surgery.

This 50-year-old woman with epilepsy seized and struck her head. Her initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 12. Her scan shows prominent right temporal bleeding. She recovered to baseline without surgery.

Signs and symptoms

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is the mainstay for rapid neurologic assessment in acute head injury. Following ascertainment of the GCS score, the examination is focused on signs of external trauma, as follows:

-

Bruising or bleeding on the head and scalp and blood in the ear canal or behind the tympanic membranes: May be clues to occult brain injuries

-

Anosmia: Common; probably caused by the shearing of the olfactory nerves at the cribriform plate [2]

-

Abnormal postresuscitation pupillary reactivity: Correlates with a poor 1-year outcome

-

Isolated internuclear ophthalmoplegia secondary to traumatic brainstem injuries: Has a relatively benign prognosis [3]

-

Cranial nerve (CN) VI palsy: May indicate raised intracranial pressure

-

CN VII palsy: May indicate a fracture of the temporal bone, particularly if it occurs in association with decreased hearing

-

Hearing loss: Occurs in 20–30% of patients with head injuries [4]

-

Dysphagia: Raises the risk of aspiration and inadequate nutrition [5]

-

Focal motor findings: Include flexor or extensor posturing, tremors and dystonia, impairments in sitting balance, and primitive reflexes; may be manifestations of a localized contusion or an early herniation syndrome

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Bedside cognitive testing

In the acute setting, measurements of the patient's level of consciousness, attention, and orientation are of primary importance.

Some patients acutely recovering from head trauma demonstrate no ability to retain new information. Mental status assessments have validated the prognostic value of the duration of posttraumatic amnesia; patients with longer durations of posttraumatic amnesia have poorer outcomes. [6]

In the long-term setting, the following bedside cognitive tests can be employed:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

-

Luria "fist, chop, slap" sequencing task: To rapidly assess motor regulation

-

Antisaccade task: Impaired in patients with symptomatic brain injury; the sensitivity of this test in detecting brain injury has been questioned [7]

-

Letter and category fluency: To provide information about self-generative frontal processes.

-

Untimed Trails B test: Allows further qualitative testing of frontal functioning

Laboratory studies

-

Sodium levels: Alterations in serum sodium levels occur in as many as 50% of comatose patients with head injuries [8] ; hyponatremia may be due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) or cerebral salt wasting; elevated sodium levels in head injury indicate simple dehydration or diabetes insipidus

-

Magnesium levels: These are depleted in the acute phases of minor and severe head injuries

-

Coagulation studies: Including prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and platelet count; these are important to exclude a coagulopathy

-

Blood alcohol levels and drug screens: May help to explain subnormal levels of consciousness and cognition in some patients with head trauma

-

Renal function tests and creatine kinase levels: To help exclude rhabdomyolysis if a crush injury has occurred or marked rigidity is present

-

In 2018, a commercially available blood test for mild brain injury was approved by the FDA. [11] This test reportedly identifies 98% of patients with abnormal head CT scans.

Imaging studies

-

Computed tomography scanning: The main imaging modality used in the acute setting

-

Magnetic resonance imaging: Typically reserved for patients who have mental status abnormalities unexplained by CT scan findings

Electroencephalography

Although certain electroencephalographic patterns may have prognostic significance, considerable interpretation is needed, and sedative medications and electrical artifacts are confounding. The most useful role of electroencephalography (EEG) in head injuries may be to assist in the diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Intracranial pressure

If the intracranial pressure rises above 20–25 mm Hg, intravenous mannitol, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and hyperventilation can be used. If the intracranial pressure does not respond to these conventional treatments, high-dose barbiturate therapy is permissible. [12]

Another approach used by some clinicians is to focus primarily on improving cerebral perfusion pressure as opposed to intracranial pressure in isolation.

Decompressive craniectomies are sometimes advocated for patients with increased intracranial pressure refractory to conventional medical treatment.

Hypertonicity

Dantrolene, baclofen, diazepam, and tizanidine are current oral medication approaches to hypertonicity. Baclofen and tizanidine are customarily preferred because of their more favorable side-effect profiles.

Subdural hematomas

Traditionally, the prompt surgical evacuation of subdural hematomas was believed to be a major determinant of an optimal outcome. However, research indicates that the extent of the original intracranial injury and the generated intracranial pressures may be more important than the timing of surgery.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Head injury can be defined as any alteration in mental or physical functioning related to a blow to the head. Loss of consciousness does not need to occur. The severity of head injuries is most commonly classified by the initial postresuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, which generates a numerical summed score for eye, motor, and verbal abilities. Traditionally, a score of 13–15 indicates mild injury, a score of 9–12 indicates moderate injury, and a score of 8 or less indicates severe injury. However, some studies have included those patients with scores of 13 in the moderate category, while only those patients with scores of 14 or 15 have been included as mild. [13] Concussion and mild head injury are generally synonymous.

Research on head injury has advanced considerably in the last decade. As is typical of many endeavors, these efforts have exposed the complexity of this condition more deeply and have helped researchers and physicians to abandon crude simplifications. This review concentrates primarily on current developments in the diagnosis and management of closed head injuries in adults.

Pathophysiology

Structural changes

Gross structural changes in head injury are common and often obvious both on autopsy and conventional neuroimaging. The skull can fracture in a simple linear fashion or in a more complicated depressed manner, in which bone fragments and pushes beneath the calvarial surface. In patients with mild head injury, a skull fracture markedly increases the chance of significant intracranial injury.

Both direct impact and contrecoup injuries, in which the moving brain careens onto the distant skull opposite the point of impact, can result in focal bleeding beneath the calvaria. Such bleeding can result in an intracerebral focal contusion or hemorrhage as well as an extracerebral hemorrhage. Extracerebral hemorrhages are primarily subdural hemorrhages traditionally ascribed to tearing of bridging veins, but epidural hemorrhages from tearing of the middle meningeal artery or the diploic veins are also common. Occasionally, subdural hemorrhages can result from disruption of cortical arteries. This type of subdural hemorrhage is rapidly progressive and can occur after trivial head injury in elderly patients. [14]

Newer perspectives conceive of chronic subdural hematomas as almost neoplastic processes that are initiated by injuries to dural border cells with subsequent angiogenesis and formation of neomembranous tissues. [15]

A landmark study of CT images from 753 patients with severe head injury from the US National Institutes of Health's Traumatic Coma Data Bank found evidence of intracranial hemorrhagic lesions in 27%. Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage was even more frequent and occurred in 39% of patients. Furthermore, diffuse cerebral edema also was present in 39%. Cerebral edema can be unilateral or diffuse and can occur even in the absence of intracranial bleeding. Severe brain edema probably occurs more commonly in children than in adults. [16]

Neuronal loss is also important. A pathological study found that quantitative loss of neurons from the dorsal thalamus correlated with severe disability and vegetative state outcomes in patients with closed head injuries. [17]

Finally, axonal injury increasingly has been recognized as a structural sequela of brain injury. The use of amyloid precursor protein staining has resulted in increased recognition of this form of injury. Using this technique, researchers have readily identified axonal injury in patients with mild head injury. Interestingly, a prominent locus of axonal damage has been the fornices, which are important for memory and cognition. [18] More severe and diffuse axonal injury has been found to correlate with vegetative states and the acute onset of coma following injury. [19]

Neurochemical changes

After traumatic brain injury, the brain is bathed with potentially toxic neurochemicals. Catecholamine surges have been documented in the plasma (higher catecholamine levels correlated with worse clinical outcomes) and in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with head injuries (higher CSF 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (HIAA), the serotonin metabolite, correlated with worse outcomes). [20] In addition, the excitotoxic amino acids (ie, glutamate, aspartate) initiate a cascade of processes culminating in an increase in intraneuronal calcium and cell death. Researchers using a microdialysis technique have correlated high CSF levels of excitotoxic amino acids with poor outcomes in head injury. [21]

Although neuroprotective strategies employing antiexcitotoxic pharmacotherapies were effective in diminishing the effects of experimental brain injuries in laboratory animals, clinical trials in humans generally have been disappointing. [22] These failures have prompted development of more complex models of neuronal injury and cell death. Researchers have demonstrated that although certain types of glutamate antagonists may protect against acute cell death, they potentiate slowly progressive neuronal injury in experimental rodent models. Still others have found that low-dose glutamate administered before brain injury is somehow neuroprotective. Such dose and timing effects are only beginning to be understood. [23]

Prostaglandins, inflammatory mediators produced by membrane lipid breakdown, are also elevated dramatically in the plasma of patients with moderate-to-severe head trauma during the first 2 weeks after injury. Patients with higher prostaglandin levels had significantly worse outcomes than those with more modest elevations. Furthermore, levels of a thromboxane metabolite, a potent vasoconstricting prostaglandin, were elevated disproportionately. [24] Such a process may underlie posttraumatic vasospasm, which has been documented in some, but not all, transcranial Doppler studies of patients with closed head injuries, even in patients without traumatic subarachnoid bleeds. [25] Delayed clinical deterioration could represent ischemia from such vasospasm, particularly in younger patients. [26]

Head injury also causes the release of free radicals and the breakdown of membrane lipids. Panels of plasma metabolites related to fatty acid and lipid breakdown products have been found to be elevated in mildly concussed athletes compared to controls. [27]

Other inflammatory biomarkers have yielded complex and contradictory results. However, overall some initial inflammation may promote recovery, but prolonged or high levels of inflammation could be detrimental. [28, 29] For example, in severely brain-injured patients a group of CSF inflammatory mediators including interleukin 6 and 8 discriminated between good versus poor 6-month outcomes with higher levels of these inflammatory mediators occurring in those with poorer outcomes. [30] Additionally, acute elevations of interleukin species along with Galactin-3, an interleukin regulator, were found in the CSF of severely brain-injured patients compared to controls. [31]

In addition to structural and chemical changes, gene expression is altered following closed head injury. Genes involving growth factors, hormones, toxin-binders, apoptosis (programmed cell death), and inflammation have all been implicated in rodent models. For example, in a mouse model of head injury, elevated levels of the transcription factor p53 were found. p53 translocates to the nucleus and initiates apoptosis or programmed cell death. Such a process could account for the delayed neuronal loss seen in head injuries. [32] Furthermore, in humans, differential activation of inflammatory regulatory genes has been associated with the worse outcomes observed in elderly patients with closed head injuries compared to their younger counterparts. [33]

Secondary insults

Hypotension and hypoxia cause the most prominent secondary trauma-induced brain insults. Both hypoxia and hypotension had adverse impacts on outcomes of 716 patients with severe head injuries from the Traumatic Coma Data Bank in the United States. Efforts to limit hypoxic injury with in-field intubation have been unsuccessful. Indeed, a multicenter study of 4098 patients with severe traumatic brain injury found that in-field intubation was associated with a dramatic increase in death and poor long-term neurologic outcome, even after controlling for injury severity. [34] More current epidemiologic research supports the lack of benefit of early intubation. [35]

In the Trauma Coma Data Bank study, hypotension was even more significant than hypoxia and, by itself, was associated with a 150% increase in mortality rate. Systemic hypotension is critical because brain perfusion diminishes with lower somatic blood pressures. Brain perfusion (ie, cerebral perfusion pressure) is the difference between the mean arterial pressure and intracranial pressure. The intracranial pressure is increased in head injury by intracranial bleeding, cell death, and secondary hypoxic and ischemic injuries. Accordingly, another study reported that death and increased disability outcomes correlated with the durations of both systemic hypotension and elevated intracranial pressures. [36]

Severe anemia often co-exists with head injuries. A multicenter study noted increased mortality at 6 months among anemic head-inured patients. [37] Nevertheless, blood transfusions have been associated with increased mortality and complications among 1250 ICU-admitted patients with brain injuries. This relationship held even after controlling for the degree of anemia. [38] Similarly, adverse thromboembolic events occurred among 200 severely head-injured patients treated with erythropoetin and transfusions in a randomized, controlled trial. [39] However, a 2016 meta-analysis of 24 primarily observational studies reported no increased risk of mortality in anemic, head-injured patients who were transfused. [40]

Finally, posttraumatic cerebral infarction occurs in up to 12% of patients with moderate and severe head injuries and is associated with a decreased Glasgow Coma Scale, low blood pressure, and herniation syndromes. [41]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

In the United States in 2020, there were approximately 214,110 TBI-related hospitalizations. In 2021, there were 59,473 TBI-related deaths. [1]

In 2003, elderly persons with head injuries exhibited a doubling in hospitalizations and deaths compared to the national average. [42] This trend has persisted with Canadian, European, and US data demonstrating an increased frequency and severity of traumatic brain injury in the elderly, primarily secondary to falls, while motor vehicular causes have decreased. [43, 44, 45, 46]

International

Head injury data are difficult to compare internationally for multiple reasons, including inconsistencies and complexities of diagnostic coding and inclusion criteria, case definitions, ascertainment criteria (eg, hospital admissions versus door-to-door surveys), transfers to multiple care facilities (eg, patient admissions may be counted more than once), and regional medical practices, such as the development in the United States of more outpatient, as opposed to inpatient, services for those with mild head injuries. Adding to this complexity is the finding that some individuals with cognitive and emotional sequelae from mild head injury may not establish the casual connection between their injury and its consequences. Such patients may not seek treatment and may not be expressed in official demographic data. [47, 48]

Despite such obstacles, one meta-analysis extrapolated head injury rates to total population estimates and found that Southeast Asian and Western Pacific nations carried the heaviest global head injury burden. [49]

Mortality/morbidity

According to the CDC, there were 59,473 TBI-related deaths in 2021. [1]

Race

A study of intentional head injury from Charlotte, North Carolina, found minority status was a major predictor of intentional head injury, even after controlling for other demographic factors. [50] Furthermore, worse clinical outcomes have been described for African American children with moderate-to-severe head injuries compared with their white counterparts. [51] In a retrospective Pennsylvania study, Blacks were more likely than nonBlacks to experience a TBI. [52] Other studies have found no increased mortality in Black versus White head-injured subjects. [53]

American Indian/Alaska Native children and adults have higher rates of TBI-related hospitalizations and deaths than other racial or ethnic groups. Factors that contribute to this disparity include higher rates of motor vehicle crashes, substance use, and suicide as well as difficulties in accessing appropriate health care. [54]

Sex

In the United States in 2020, males were nearly two times more likely to be hospitalized (79.9 age-adjusted rate vs 43.7) and three times more likely to die from a TBI than females (28.3 vs 8.4). [1]

Age

Approximately half of the patients admitted to a hospital for head injury are aged 24 years or younger. In 2022, 2.3 million (3.2%) children and adolescents aged ≤ 17 years had ever received a diagnosis of a concussion or brain injury. [46]

In 2020, people age 75 years and older had the highest numbers and rates of TBI-related hospitalizations and deaths. [1] This age group accounts for about 32% of TBI-related hospitalizations and 28% of TBI-related deaths.

The rates of emergency room visits for the head-injured elderly are more than three times higher for those over 84 years of age compared to those between 65 to 74 years of age. [55]

Prognosis

Head injuries may result in death, a vegetative state, partial recovery, or full return to work. Each patient presents with a unique baseline neurological makeup, mechanisms of injury, secondary complications, and postinjury adjustment and support system.

The most important prognostic factors are probably age, mechanism of injury, postresuscitation GCS score, postresuscitation pupillary reactivity, postresuscitation blood pressures, intracranial pressures, duration of posttraumatic amnesia or confusion, sitting balance, and intracranial pathology identified on neuroimaging. The Brain Trauma Foundation, a research consortium focusing on developing evidence-based practices, emphasizes postresuscitation GCS, pupils, age, hypotension, and CT findings as the most important outcome predictors. [56]

The mortality rate of severe head injuries ranges from 25% to 36% in adults within the first 6 months after injury. Most deaths occur within the first 2 weeks. A 2022 study of all levels of severity of head injury reported 21% with death or an unfavorable outcome at 6 months. Even 5.6% of mild head-injured patients experienced death or unfavorable outcomes. [57]

-

A study of 216 patients hospitalized during 2003–2005 in Ireland found 97% of patients with mild head injury attained a good recovery as measured by the Glasgow Outcome Scale, while 82% of the patients with severe head injury were either vegetative or markedly disabled. After 1 year, 11% of the total patients were unable to work. [58]

-

Another contemporary study of 309 Italian patients with moderate head injury found that only 15% were vegetative or severely disabled after 6 months. Basal skull fractures, subarachnoid hemorrhages, coagulopathies, subdurals, and poor emergency room clinical status predicted these unfavorable outcomes. [59]

-

Conversely, in Germany only 82% of 67 patients with mild or moderate head injury experienced a good 1-year outcome, and only 73% were able to return to work. Subjective complaints persisted in a large minority, with more than one third of patients reporting drowsiness, fatigue, forgetfulness, poor concentration, and irritability. [60] Other studies have identified dizziness along with analgesic and psychotropic medication use as predictors of failure to return to work after mild and moderate head injuries. [61]

-

A 5-year paid employment status study of 5683 moderate to severely head-injured patients found that not only did age and injury severity adversely affect stable employment, but so did lack of transportation and elevated anxiety levels. Only 27% attained stable 5-year employment. [62] Another study reported that 41% of 4927 moderate and severe head-injured patients attained full or part-time paid employment at year 5. [63]

-

Overall, patients with traumatic brain injury are 2.23 times more likely to die than their non-injured counterparts. Brain-injured patients' life expectancies are reduced by about 9 years. [64]

-

An Australian study of patients with head injuries incurred from 1984 to 1991 found that all 59 patients who were aged 65 or older and scored less than 11 on the postresuscitation GCS either died or were left with severe disability. Furthermore, even after controlling for injury severity and GCS scores, a current study of head-injured elderly motor vehicle accident victims demonstrated more than 3 times the mortality compared with their younger counterparts. [65, 66] Similar results were documented in a study of severely head-injured elders from Norway with 72% attaining an unfavorable outcome, defined as inability to be independent when out of their home environment. [67]

-

A several decades-long study of more than 17,000 moderate and severe brain-injured patients between 25 and 56 years old found that 98% recovered consciousness upon discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. However, the researchers cautioned that their findings may not be generalizable because sicker patients may have had care withdrawn or may have not been eligible for inpatient rehabilitation in the first place. [68]

Patient Education

The physician may be hesitant to suggest to patients that problems may arise from a mild head injury. Such information may induce the expectations of symptoms when no symptoms are present and arouse anxiety. However, at least one study has shown that patients with head injury who were contacted by phone and offered education about their injury and follow-up care experienced significantly fewer postconcussive symptoms and less disruption of social activities. [69]

At present, most patients incurring a head injury probably should be informed that cognitive and emotional dysfunction as well as head pain and other somatic symptoms are not uncommon in the aftermath. At least in mild injuries, these symptoms typically are self-limited, and most people return to normal functioning after a few weeks to months.

-

This 50-year-old woman with epilepsy seized and struck her head. Her initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 12. Her scan shows prominent right temporal bleeding. She recovered to baseline without surgery.

-

This 50-year-old man was struck in the head in an assault. His scan shows a right acute subdural hematoma with no mass effect. His initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15. He returned home without major sequelae after 5 days of hospitalization.

-

This is a superior view of the CT scan shown in the previous image. This demonstrates a small left frontal intracranial contusion with some surrounding edema. This could be a marker of axonal injury.

-

This 23-year-old woman was in a motor vehicle accident with impact on the left. Her initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 6 and she required intubation. Her scan shows a subtle right posterior frontal linear hyperdensity, most likely a small petechial bleed (contrecoup). This could also be a marker of axonal injury.

-

This 35-year-old man was in a motor vehicle accident. His initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 7. He had left hemiparesis. He recovered orientation to temporal parameters after 1 week, but he remained disinhibited and hemiparetic (although able to ambulate). His MRI shows a diffusion-weighted hyperintensity in the right posterior internal capsular limb. This was attributed to an axonal injury. (An embolic workup for stroke was unremarkable, and no dissection was discerned on a carotid Doppler study.)

-

This 40-year-old woman was anticoagulated with warfarin (Coumadin) and fell out of her hospital bed. She subsequently died. Her CT scan shows an obvious right subdural hematoma with mass effect.

-

This elderly woman had a history of frequent falls and presented with seizures, possibly from her right hypodense subdural hematoma shown here. The subdural hematoma appears chronic and exhibits no mass effect.

-

This 23-year-old freelance graphic artist has drifted from job to job following his head injury 2 years prior to this scan. He was hospitalized initially for about 1 week for intracranial bleeding. This CT scan shows obvious medial bifrontal atrophy.