Background

Ischemic strokes occurring in the anterior circulation are the most common of all ischemic strokes, accounting for approximately 70% of all cases. They are caused most commonly by occlusion of one of the major intracranial arteries or of the small single perforator (penetrator) arteries.

Origins and sites of occlusion

The most common causes of arterial occlusion involving the major cerebral arteries are (1) emboli, most commonly arising from atherosclerotic arterial narrowing at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, from cardiac sources, or from atheroma in the aortic arch and (2) a combination of atherosclerotic stenosis and superimposed thrombosis. Lacunar strokes are believed to be caused by lipohyalinotic intrinsic disease of the small penetrating vessels.

The most common sites of occlusion of the internal carotid artery are the proximal 2 cm of the origin of the artery and, intracranially, the carotid siphon. Factors that modify the extent of infarction include the speed of occlusion and systemic blood pressure.

Occlusion of the internal carotid artery is not infrequently silent, because external orbital-internal carotid and willisian collaterals can open up if the occlusion has occurred gradually over a period of time.

Mechanisms of ischemia resulting from internal carotid artery occlusion are, most commonly, artery-to-artery embolism or propagating thrombus and perfusion failure from distal insufficiency.

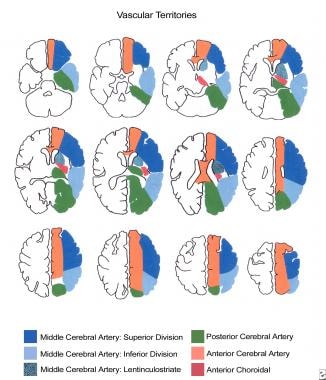

The middle cerebral artery (MCA) is the largest of the intracerebral vessels and supplies through its pial branches almost the entire convex surface of the brain, including the lateral frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes; insula; claustrum; and extreme capsule. The lenticulostriate branches of the MCA supply the basal ganglia, including the caput nuclei caudati, the putamen, the lateral parts of the internal and external capsules, and sometimes the extreme capsule.

Occlusion of the MCA commonly occurs in either the main stem (M1) or in one of the terminal superior and inferior divisions (M2). Occlusion of the M1 segment of the MCA prior to the origin of the lenticulostriate arteries in the presence of a good collateral circulation can give rise to the large striatocapsular infarct.

Occlusion of the MCA or its branches is the most common type of anterior circulation infarct, accounting for approximately 90% of infarcts and two thirds of all first strokes. Of MCA territory infarcts, 33% involve the deep MCA territory, 10% involve superficial and deep MCA territories, and over 50% involve the superficial MCA territory.

The anterior cerebral artery (ACA) supplies the whole of the medial surfaces of the frontal and parietal lobes, the anterior four fifths of the corpus callosum, the frontobasal cerebral cortex, the anterior diencephalon, and the deep structures. Occlusion of the ACA is uncommon, occurring in only 2% of cases, often through atheromatous deposits in the proximal segment of the ACA.

The anterior choroidal artery supplies the lateral thalamus and posterior limb of the internal capsule. Occlusion of the anterior choroidal artery occurs in less than 1% of anterior circulation strokes. Often, ischemia in the distribution of the ophthalmic artery is transient in the setting of symptomatic internal carotid artery occlusion (ie, transient monocular blindness, occurring in approximately 25% of patients), but central retinal artery ischemia is relatively uncommon, presumably because of the efficient collateral supply.

Occlusion of single penetrating branches of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries that supply the deep white and gray matter produce the lacunar type of stroke. These occlusions account for as many as 20% of ischemic strokes.

Population differences

The patterns of arterial occlusion are different in Blacks and Asians than in Whites.

Asians and Blacks have higher rates of intracranial arterial occlusive disease than Whites. The intracranial arterial occlusive disease in these populations typically involves the main stem of the MCA or the ACA.

In Whites, the arterial occlusive disease typically involves the extracranial carotid arteries, and lesions in the middle and anterior cerebral arteries are usually of embolic origin.

Circulatory Anatomy

The anterior circulation of the brain describes the areas of the brain supplied by the right and left internal carotid arteries and their branches. The internal carotid arteries supply the majority of both cerebral hemispheres, except the occipital and medial temporal lobes, which are supplied from the posterior circulation, as shown in the image below.

The internal carotid artery originates at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery at the level of the thyroid cartilage in the neck. The extracranial portion of the artery passes into the carotid canal of the temporal bone without giving off any branches. The intracranial portion of the artery consists of the petrosal, cavernous (ie, S-shaped carotid syphon), and supraclinoid portions.

The major intracranial branches arise from the supraclinoid portion, the first being the ophthalmic artery that enters the orbit through the optic foramen to supply the retina and optic nerve. Next, the posterior communicating artery arises just distal to the ophthalmic artery and joins the posterior cerebral artery.

The anterior choroidal artery arises prior to the terminal bifurcation of the internal carotid artery into the middle cerebral and anterior cerebral arteries. The MCA is the direct continuation of the artery, while the ACA branches medially at the level of the anterior clinoid process. The circle of Willis consists of a vascular communication of blood vessels at the base of the brain connecting the major vessels of the anterior and posterior circulations.

The collateral circulation is an important potential source of blood supply in cases of internal carotid artery occlusive disease. The 2 primary sources of collateral flow via the circle of Willis are the anterior and the posterior communicating arteries. Blood may flow from the contralateral ICA via the A1 segment of the contralateral anterior cerebral artery through the anterior communicating artery to the ipsilateral ACA (appears as reversal of flow). Blood may come from the posterior circulation (posterior cerebral arteries) via the posterior communicating artery (reversal of flow).

Note that a high degree of variation exists in the normal vascular anatomy of the circle of Willis. For example, in as many as 20% of patients, the posterior cerebral arteries (ie, fetal variant) arise from the internal carotid artery as normal vascular variants. Therefore, some variation exists in the exact parts of the brain supplied by the anterior circulation.

If the primary collateral circulation fails, secondary sources of collaterals may come from the branches of the ipsilateral external carotid artery. Branches from the maxillary artery anastomose with the ophthalmic artery leading to reversal of flow in the ophthalmic artery and into the occluded ICA. Leptomeningeal collaterals may also anastomose with distal MCA branches and lead to reversed flow in the MCA.

Pathophysiology

The acute ischemic process varies markedly from patient to patient. Patients with similar clinical syndromes may have markedly different pathophysiologic profiles. Many new pathophysiologic insights have been obtained from studies using functional brain imaging (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], positron emission tomography [PET] scanning, single-photon emission computed tomography [SPECT] scanning).

Several pathophysiologic ischemic stroke syndromes can be identified on the basis of imaging parameters of perfusion and tissue injury that could be used to target stroke treatment.

Using new MRI methods, the following three patterns have been identified.

The first pattern, perfusion-diffusion mismatch, may represent a situation of viable, but ischemic, tissue that could be salvaged by timely reperfusion. In this pattern, a larger area of hypoperfusion surrounds a zone of ischemic injury on diffusion-weighted imaging. This pattern occurs in approximately 70% of patients in the first 24 hours. In many patients, an arterial occlusion is identified on MR angiography (MRA).

The second pattern is complete ischemia, in which the perfusion and diffusion lesions are of equivalent size, likely representing a complete infarct. This pattern has been identified in approximately 10–20% of patients in the first 24 hours. In many patients, an arterial occlusion is identified on MRA.

The third pattern is the reperfusion pattern, in which a perfusion deficit no longer exists and the MRA is normal. This pattern occurs in approximately 10–15% of patients in the first 24 hours.

Reperfusion is an important part of the ischemic process, and by 24 hours, 20–40% of arterial occlusions have begun to clear, with recanalization rates of 70% by 1 week and 90% by 3 weeks.

Early reperfusion (< 24 h) may have significant prognostic benefits and is associated with improved outcome and smaller infarct size, but later reperfusion may not alter outcome significantly and may be associated with hemorrhagic conversion of the infarct and edema formation.

Etiology

Risk factors for anterior circulation stroke include those that are not modifiable and those that potentially are modifiable.

Risk factors for anterior circulation stroke include the following:

-

Age (risk rises exponentially with age)

-

Sex (more common in males at all ages)

-

Race (African American > Asian > Caucasian)

-

Geography (Eastern Europe > Western Europe > Asia > rest of Europe or North America)

-

Genetic risk factors (stroke or heart disease in individuals younger than 60 y; some familial syndromes, eg, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy [CADASIL])

Potentially modifiable risk factors [1] for anterior circulation stroke include the following:

-

Hypertension (diastolic or isolated systolic)

-

Diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2

-

Atrial fibrillation

-

Smoking

-

Coronary artery disease

-

Hypercholesterolemia

-

Alcohol abuse

-

Drug abuse (eg, cocaine)

-

Oral contraceptive use

-

Pregnancy

Epidemiology

Incidence

Approximately 795,000 new and recurrent cases of stroke occur each year in the United States. Approximately 87% of these are ischemic strokes. Anterior circulation ischemic stroke accounts for approximately 70% of all ischemic strokes. Approximately 420,000 new cases of anterior circulation ischemic stroke per year are reported in the United States. [2]

In 2020, the global prevalence of all stroke subtypes was 89.13 million cases. [2] Globally, stroke is the second-leading cause of death and the third leading cause of death and disability. [3]

Demographics

Although strokes can occur at any age, the incidence of stroke rises exponentially with age, particularly in individuals older than age 55 years. [1] However, 25% of all strokes occur in individuals younger than age 65 years; so stroke is not just a condition of the elderly.

Risk of having a first stroke is nearly twice as high for nonHispanic Black adults as for White adults. This may relate in part to higher rates of some vascular risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, in the Black population. Stroke risks are also higher in Hispanics and Asians, relative to Whites. [2]

Strokes at all ages are more likely to occur in men, but overall, more strokes occur in women and women of all ages are more likely than men are to die from stroke. [4] This is because strokes occur more commonly at older ages, and females have a longer life span than do males (the native protective effect of estrogen is lost at menopause). This disparity may become greater in the future with the aging of the population.

Recurrence

Stroke recurs in as many as 10% of stroke survivors in the first 12 months after stroke, with an incidence of 4% per year thereafter. After transient ischemic attack, the risk of stroke is 10.5% over the next 3 months, with the highest risk in the 2 days following a transient ischemic attack (TIA).

Prognosis

High rates of morbidity and mortality are associated with all types of ischemic strokes, but the prognosis varies among subtypes. For example, mortality rates after intracerebral hemorrhage are as high as 30% at 1 month.

Conversely, the ischemic lacunar syndromes (ie, caused by occlusion of a single small penetrating artery) quite often are associated with a good prognosis and have a better prognosis than MCA syndromes.

Overall, at 6 months after a stroke, as many as 30% of patients have died, 20–30% are moderately to severely disabled, 20–30% have mild to moderate disability, and 20–30% are without deficits.

Patient Education

Educate patients and their families regarding stroke, its treatment, its complications, and plans for future care.

A significant percentage of patients (ie, as many as 50% in some studies) suffer from depression after stroke. Also, a significant rate of stress and depression exists among caregivers of patients disabled by stroke. Provide referrals to stroke support groups.

Provide educational material from organizations such as the American Stroke Association and the National Stroke Association.

For patient education information, see Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA, Mini-stroke).