Practice Essentials

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), also known as idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (INPH), is a clinical symptom complex caused by the build-up of cerebrospinal fluid. This condition is characterized by abnormal gait, urinary incontinence, and (potentially reversible) dementia. See the image below.

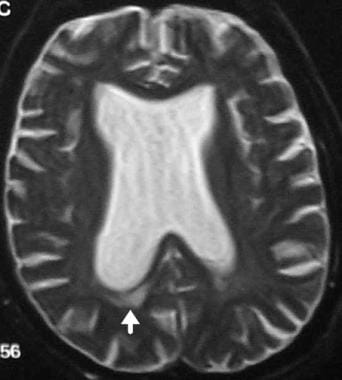

T2-weighted MRI showing dilatation of ventricles out of proportion to sulcal atrophy in a patient with normal pressure hydrocephalus. The arrow points to transependymal flow.

T2-weighted MRI showing dilatation of ventricles out of proportion to sulcal atrophy in a patient with normal pressure hydrocephalus. The arrow points to transependymal flow.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with NPH present with a gradually progressive disorder. The classic triad consists of the following:

-

Abnormal gait: Earliest feature and most responsive to treatment; bradykinetic, broad-based, magnetic, and shuffling gait

-

Urinary incontinence: Urinary frequency, urgency, or frank incontinence

-

Dementia: Prominent memory loss and bradyphrenia; forgetfulness, decreased attention, inertia

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory testing

In general, laboratory testing is not helpful in the diagnosis of NPH. However, a levodopa challenge may be helpful to rule out idiopathic Parkinson disease; patients with NPH have no significant response to levodopa or dopamine agonists.

Imaging studies

Imaging studies are invaluable in the diagnosis of NPH. In most cases of new-onset neurologic symptoms, obtain an initial computed tomography scan of the brain. Although magnetic resonance imaging is more specific than CT scanning in NPH, a normal CT scan can exclude the diagnosis.

Procedures

All patients with suspected NPH should undergo diagnostic CSF removal (either large volume lumbar puncture and/or external lumbar drainage), which has both diagnostic and prognostic value. Improvement in symptoms with large-volume drainage supports the diagnosis of NPH.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Surgery

Surgical CSF shunting remains the main treatment modality for NPH. Prior to embarking upon surgical therapy, knowing which patients may benefit from surgery is necessary. Detailed testing is performed before and after CSF drainage (eg, baseline neuropsychological evaluation, timed walking test, large-volume lumbar puncture, external lumbar drainage, CSF infusion testing).

Ideal candidates for shunt surgery would show imaging evidence of ventriculomegaly, as indicated by a frontal horn ratio exceeding 0.50 on imaging studies, along with one or more of the following criteria:

-

Presence of a clearly identified etiology

-

Predominant gait difficulties with mild or absent cognitive impairment

-

Substantial improvement after CSF withdrawal (CSF tap test or lumbar drainage)

-

Normal-sized or occluded sylvian fissures and cortical sulci on CT scan or MRI

-

Absent or moderate white-matter lesions on MRI

An alternative technique to shunt surgery is endoscopic third ventriculostomy.

Pharmacotherapy

No definitive evidence exists that medication, including levodopa/carbidopa, can successfully treat NPH. Although levodopa/carbidopa has been reported to be of benefit in anecdotal reports, patients with NPH may represent misdiagnosed cases of parkinsonism. However, in patients who are poor candidates for shunt surgery, repeated lumbar punctures in combination with acetazolamide may be considered. [1]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), also known as idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (INPH), is a clinical symptom complex characterized by abnormal gait, urinary incontinence, and dementia. It is an important clinical diagnosis because it is a potentially reversible cause of dementia. NPH describes hydrocephalus in the absence of papilledema and with normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure on lumbar puncture. [2] Even though CSF pressure is not elevated, the condition typically responds to a reduction in CSF pressure. [3]

Pathophysiology

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) differs from other causes of adult hydrocephalus. An increased subarachnoid space volume does not accompany increased ventricular volume. Clinical symptoms result from distortion of the central portion of the corona radiata by the distended ventricles. This may also lead to interstitial edema of the white matter and impaired blood flow, as suggested in nuclear imaging studies. The periventricular white matter anatomically includes the sacral motor fibers that innervate the legs and the bladder, thus explaining the abnormal gait and incontinence. Compression of the brainstem structures (ie, pedunculopontine nucleus) could also be responsible for gait dysfunction, particularly the freezing of gait that has been well described. Dementia results from distortion of the periventricular limbic system.

The term normal pressure hydrocephalus was based on the finding that all 3 patients reported by Hakim and Adams showed low CSF pressures at lumbar puncture, namely 150, 180, and 160 mm H2 O. However, an isolated CSF pressure measurement by lumbar puncture clearly yields a poor estimation of the real intracranial pressure (ICP) in patients with NPH.

Hakim first described the mechanism by which a normal or high-normal CSF pressure exerts its effects. Using the equation, Force = Pressure X Area, increased CSF pressure over an enlarged ependymal surface applies considerably more force against the brain than the same pressure in normal-sized ventricles. Normal pressure hydrocephalus may begin with a transient high-pressure hydrocephalus with subsequent ventricular enlargement. With further enlargement of the ventricles, CSF pressure returns to normal; thus the term NPH, at least in view of the initial pathophysiologic events, is a misnomer. Intermittent intracranial hypertension has been noted in some patients.

Some authors prefer the term extraventricular obstructive hydrocephalus. They believe that the initial event is diminished CSF absorption at the arachnoid villi. This obstruction to CSF flow leads to transient high-pressure hydrocephalus with subsequent ventricular enlargement. As the ventricles enlarge, CSF pressure returns to normal.

Epidemiology

A Norwegian study of a population of 220,000 inhabitants found a prevalence of probable idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (INPH) of 21.9 per 100,000 population and an incidence of 5.5 per 100,000 population; the investigators suggested that those numbers be regarded as minimum estimates. The study also showed that the incidence and prevalence of NPH increases with age. [4]

A Japanese study found radiological and clinical features consistent with INPH in 2.9% of community-dwelling elderly subjects. [5]

In another Japanese study, elderly individuals (age > 65 y) underwent MRI and the prevalence of NPH was 1.4%. [6]

The prevalence of NPH may be as high as 14% in extended care facility patients. [7]

Prognosis

The overall prognosis of normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) remains poor both due to a lack of improvement in some patients following surgery as well as a significant complication rate. In a study by Vanneste et al, one of the more comprehensive studies described above, marked improvement was noted in only 21% of patients following shunt surgery. Complication rate was approximately 28% with death or severe residual morbidity in 7% of patients, further emphasizing the importance of careful patient selection. [8] Concomitant cerebrovascular disease is a recognized negative prognostic factor. [9]

In a small prospective study, investigators measured the impact of cortical Alzheimer disease pathology on shunt responsiveness in 37 individuals treated for idiopathic NPH. Clinical measures, including neuropsychometrics and gait, were correlated with amyloid β (Aβ) plaques, neuritic plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles observed in cortical biopsies obtained during shunt insertion. Patients with no tau and Aβ pathology and mild tau and Aβ pathology improved on the neuropsychometric and gait evaluations. In contrast, patients with moderate-to-severe pathology did not show improvement on any study measure. However, the relatively small numbers in the study, presence of contradictory studies, and absence of a widely accepted biomarker for Alzheimer disease make it difficult to use this finding while evaluating patients with NPH. [10]

In patients who develop recurrent symptoms after initial improvement, shunt malfunction should be suspected and an evaluation for mechanical failure should be pursued. In some of these cases, catheter migration may have occurred, which is a correctable cause of shunt malfunction. In one case series, shunt revision was required in more than half of treated patients over a 6-year period, with improvement in most of these patients. [11]

The incidence of shunt complications is estimated in 30%–40% of patients. [12] These include anesthetic complications, intracranial hemorrhage from placement of the ventricular catheter, infection, CSF hypotensive headaches, subdural hematomas, shunt occlusion, and catheter breakage. Rapid reduction in ventricular size following the shunt favors complications such as subdural hematoma, which may occur in 2%–17% of patients. [12] Dual-switch valves and programmable valves may reduce the incidence of this complication. [13]

-

T2-weighted MRI showing dilatation of ventricles out of proportion to sulcal atrophy in a patient with normal pressure hydrocephalus. The arrow points to transependymal flow.

-

CT head scan of a patient with normal pressure hydrocephalus showing dilated ventricles. The arrow points to a rounded frontal horn.

-

This image shows ventriculomegaly, which is typical in hydrocephalus ex vacuo.

-

This image shows cortical atrophy, which is the defining feature of hydrocephalus ex vacuo.