Gross Anatomy

Spinal cord disease results from multiple diverse pathologic processes. Trauma is the most common cause of spinal cord injury. Depending on its pathogenesis, spinal cord disease can manifest with variable impairment of motor, sensory, or autonomic function. This review focuses on spinal cord anatomy. Basic clinical descriptions of common patterns of spinal cord involvement are related to essential aspects of spinal cord anatomy. The spinal cord provides innervation to the trunk and limbs through the spinal nerves and their peripheral ramifications. [1]

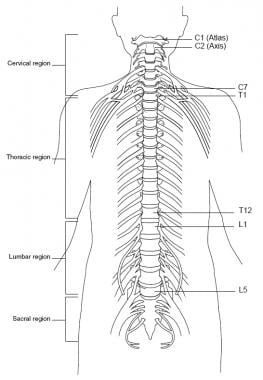

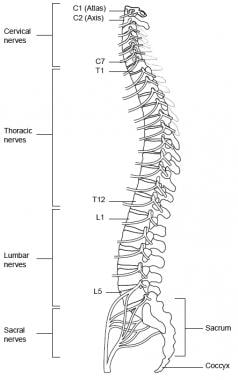

The spinal cord is located inside the vertebral canal, which is formed by the foramina of seven cervical, 12 thoracic, five lumbar, and five sacral vertebrae, which together make up the spine. The spinal meninges ensheathe the spinal cord and are continuous with the cranial meninges through the foramen magnum. The spinal cord extends from the foramen magnum down to the level of the first and second lumbar vertebrae (at birth, down to the second and third lumbar vertebrae), where it terminates as the conus medullaris, which narrows into the filum terminale anchored to the dorsum of the coccyx (see the image below). [1]

The spinal cord is composed of the following 31 segments:

-

Eight cervical (C) segments

-

Twelve thoracic (T) segments

-

Five lumbar (L) segments

-

Five sacral (S) segments

-

One coccygeal (Co) segment - Mainly vestigial

The spinal nerves consist of the sensory nerve roots, which enter the spinal cord at each level, and the motor roots, which emerge from the cord at each level. These nerves attach to the cord as a linear series of dorsal (afferent fibers) and ventral (efferent fibers) nerve rootlets. [1] The spinal nerves are named and numbered according to the site of their emergence from the vertebral canal. C1-C7 nerves emerge above their respective vertebrae. C8 emerges between the seventh cervical and first thoracic vertebrae. The remaining nerves emerge below their respective vertebrae (see the image below).

The dorsal rami of C1-C4 are located in the suboccipital region. C1 participates in the innervation of neck muscles, including the semispinalis capitis muscle. C2 carries sensation from the back of the head and scalp, along with motor innervation to several muscles in the neck. C3-C5 contribute to the formation of the phrenic nerve and innervate the diaphragm. C5-T1 provide motor control for the upper extremities and related muscles.

The thoracic cord has 12 segments and provides motor control to the thoracoabdominal musculature. The lumbar and sacral portions of the cord have five segments each. L2-S2 provide motor control to lower extremities and related muscles.

The conus medullaris is the cone-shaped termination of the caudal cord. The pia mater continues caudally as the filum terminale through the dural sac and attaches to the coccyx. The coccyx has only one spinal segment. The cauda equina (Latin for horse tail) is the collection of lumbar and sacral spinal nerve roots that travel caudally prior to exiting at their respective intervertebral foramina. The cord ends at vertebral levels L1-L2.

Ventral and Dorsal Roots

Ventral (motor) roots

The ventral (motor) roots of the spinal cord consist of efferent fibers that transmit motor commands from the central nervous system (CNS) to peripheral muscles. [1] The cell body (i.e., soma) is in the anterior horn within the cord parenchyma. These neurons include alpha motor neurons, which innervate extrafusal muscle fibers responsible for muscle contraction, and gamma motor neurons, which regulate intrafusal muscle fibers within muscle spindles to maintain sensitivity during muscle stretch. The ventral rootlets emerge from the ventrolateral sulcus of the spinal cord, fuse to form the ventral root, and join with dorsal roots to create mixed spinal nerves. [1, 2]

The spinal cord is organized somatotopically, with motor neurons controlling proximal muscles (e.g., trunk) located medially in the anterior horn, while those controlling distal muscles (e.g., limbs) are positioned laterally. This organization is particularly prominent in the cervical and lumbar enlargements, which accommodate the increased number of motor neurons required for upper and lower limb movements. [3]

Clinically relevant reflex center levels are as follows (spinal reflex center levels are presented in parentheses and take into account anatomic variations in innervation):

-

Biceps - C5/6

-

Brachioradialis - C5/6

-

Triceps - C7 (C6-8)

-

Finger flexors - C8 (C7-T1)

-

Knee - L3 (L2-L4)

-

Ankle - S1 (L5-S2)

Dorsal (sensory) roots

The cell bodies of the sensory nerves are located in the dorsal root ganglia. The dorsal roots of the spinal cord are composed of afferent fibers that transmit sensory information from the periphery to the CNS. [1] Each dorsal root contains the input from all the structures within the distribution of its corresponding body segment (i.e., somite). Dermatomal maps portray sensory distributions for each level. These maps differ somewhat according to the methods used in their construction.

Charts based on injection of local anesthetics into single dorsal root ganglia show bands of hypalgesia to be continuous longitudinally from the periphery to the spine. Maps derived from other methods, such as observation of herpes zoster lesion distributions or surgical root section, show discontinuous patterns. In addition, innervation from one dermatomal segment to another overlaps considerably, more so for touch than for pain. As the dermatomes travel from the back to the chest and abdomen, they tend to dip inferiorly.

Clinically important dermatomes are as follows:

-

C2 and C3 - Posterior head and neck

-

C4 and T2 - Adjacent to each other in the upper thorax

-

T4 or T5 - Nipple

-

T10 - Umbilicus

-

Upper extremity - C5 (anterior shoulder), C6 (thumb), C7 (index and middle fingers), C 7/8 (ring finger), C8 (little finger), T1 (inner forearm), T2 (upper inner arm), T2/3 (axilla)

-

Lower extremity - L1 (anterior upper-inner thigh), L2 (anterior upper thigh), L3 (knee), L4 (medial malleolus), L5 (dorsum of foot), L5 (toes 1-3), S1 (toes 4, 5; lateral malleolus)

-

S3/C1 - Anus

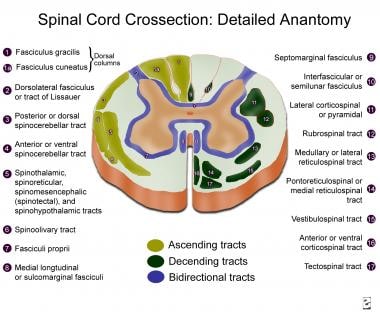

Several macroscopic grooves are discernible on the surface of the spinal cord. Most prominent is the anterior median fissure, which is occupied by the anterior spinal artery. The posterior median sulcus is less prominent. The anterior and posterior nerve rootlets emerge at the anterolateral and posterolateral sulci.

The external part of the spinal cord consists of white matter, while the internal part is composed of gray matter. The white matter includes the three funiculi: posterior, lateral, and anterior. Each contains ascending and descending tracts. A tract is usually named by a composite of its origin and destination; for example, the corticospinal tract (CST) originates at the cerebral cortex and ends at the spinal cord.

The gray matter can be divided into 10 laminae/layers or into four parts: anterior or ventral horn (i.e., motor neurons; laminae VIII, IX, and part of VII), posterior or dorsal horn (i.e., sensory part; laminae I-VI), intermediate zones (i.e., associate neurons; lamina VII), and lateral horns (i.e., part of the intermediate zone, present in the thoracic and lumbar segments, where sympathetic neurons are located).

The spinal gray matter neurons are also arranged into columns or nuclei. The substantia gelatinosa and proper sensory nucleus extend throughout the whole spinal cord and receive pain impulses. Other nuclei, such as the nucleus of Clarke, are present only in certain segments.

Descending Spinal Cord Tracts

Motor tracts

Corticospinal tract

This largest and most important descending tract exists in the cerebral cortex and is composed of over 1 million fibers (700,000 are myelinated, 90% with a diameter of 1-4 µm). Fibers arise from neurons in the deeper lamina V in the precentral gyrus (Brodmann area 4), premotor area (area 6), postcentral gyrus (areas 1, 2, 3, and 3b), and adjacent parietal cortex (area 5). Only a small part of the corticospinal tract (CST) originates from the large pyramidal cortical neurons, the 34,000-40,000 Betz cells in each hemisphere (Brodmann area 4). However, most of the large fibers (10-20 µm) originate there (see the image below).

CST fibers arise from cells arranged in strips of different sizes. Their axons converge in the corona radiata, enter the internal capsule, and form the crus cerebri in the midbrain. In the medulla, they form the pyramids. At the junction of the medulla and spinal cord, the CST incompletely decussates (75-90% of the fibers), forming the large, lateral CST; the small, anterior CST (uncrossed); and the small, uncrossed, anterolateral CST.

Fibers of the lateral CST run through the lateral funiculus, medial to the posterior spinothalamic tract and lateral to the fasciculus proprius. Axons from the lateral CST synapse with alpha motor neurons and interneurons (more commonly) from laminae IV, V, VI, and VII. The lateral CST decreases in size at the more caudal spinal cord levels, where the fibers reach the posterior (i.e., dorsal) surface of the spinal cord. Fibers from the precentral motor cortex terminate mostly in laminae VII and IX, while fibers from Brodmann areas 1, 2, 3, and 5 terminate mostly in the posterior horn.

Fibers from the anterior CST (i.e., bundle of Türck) descend uncrossed in the spinal cord, close to the anterior median fissure. The anterior CST is more developed in humans and apes than in other animals. Most fibers cross at the cervical levels, terminating bilaterally on neurons at lamina VII. It mainly modulates motor neurons that innervate neck and arm muscles.

The anterolateral CST is composed of small-diameter fibers, which run uncrossed in the lateral funiculus, more ventral than the lateral CST. They terminate in the posterior horn and intermediate gray matter.

Studies suggest molecular heterogeneity among corticospinal neurons based on their termination patterns in cervical versus lumbar spinal cord regions. This heterogeneity underpins differential functional roles, such as forelimb versus hindlimb motor control and sensory modulation. [4]

Tracts originating in the brainstem

In addition to the CST, other tracts, originating in the brainstem, descend in the spinal cord. They are involved mainly in the control of postural tone.

A tectospinal tract arises from neurons in the deep layers of the superior colliculus, crosses around the periaqueductal gray (PAG) matter, and is incorporated in the medial longitudinal fasciculus at the medulla. It descends in the anterior funiculus, near the anterior median fissure, only through cervical levels. Fibers terminate in laminae VII, VIII, and parts of VI, synapsing with interneurons. They mediate reflex postural movements in response to visual and, possibly, auditory stimuli. It integrates sensory information to coordinate head and eye movements in response to auditory and visual stimuli. [1]

A rubrospinal tract arises from magnocellular neurons (at least in primates) in the red nucleus and crosses at the ventral tegmental decussation. Stimulation of the red nucleus leads to excitation of contralateral flexor alpha motor neurons and inhibition of extensor alpha motor neurons. Fibers are organized somatotopically and terminate in the lateral half of laminae V, VI, and dorsal/central VII. Fibers mainly control the muscle tone of flexor muscle groups.

Vestibulospinal tracts arise from the lateral vestibular nucleus (i.e., Deiters' nucleus) and descend bilaterally in the anterior part of the lateral funiculus. Fibers are organized somatotopically and terminate in laminae IX, VII, and VIII, mainly in the cervical and lower lumbar segments. They facilitate spinal cord reflexes and muscle tone. Interruption of this tract eliminates decerebration. Excitatory vestibulospinal input is present at rest and during locomotion. Fibers originating in the medial vestibular nucleus project medially in the medial longitudinal fasciculus and continue in the anterior funiculus. They modulate cervical motor neurons.

Two reticulospinal tracts arise in the pontine and medullary tegmenti. The pontine reticulospinal tract has its origin in the nucleus reticularis pontis caudalis and oralis. It descends almost completely ipsilaterally in the medial part of the anterior funiculus. It mainly produces monosynaptic and polysynaptic excitation of axial (more strongly) and limb muscles.

The medial longitudinal fasciculi run in the posterior part of the anterior funiculus and originate at different brainstem levels. They form a well-defined tract only in the cervical spinal cord but descend until the sacral regions. They inhibit upper cervical motor neurons and regulate head position. Fastigiospinal fibers cross the midline and project to cervical spinal cord levels, descending in the ventral part of the lateral funiculus. Their significance in motor control is largely unknown.

These brainstem-originating tracts collectively regulate postural tone, reflexive movements, balance, and fine motor coordination. Their functional integration ensures smooth execution of voluntary movements while maintaining stability during dynamic activities. [1]

Ascending Spinal Cord Tracts

Sensory tracts

Posterior (i.e., dorsal funiculi) columns convey three different types of sensation: (1) proprioception, or position sense, for which the sensory receptors are the muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs; (2) vibratory sense, for which the receptor is the Pacinian corpuscle; and (3) discriminative touch, for which the receptor is the Meissner's corpuscle. This information is carried by large, myelinated (i.e., A alpha or type Ia) fibers in the sensory nerves. Some evidence indicates a possible role for the dorsal columns in visceral pain transmission (see the image below). [5] Studies have demonstrated that lesions in the dorsal columns can alleviate certain types of visceral pain, suggesting the presence of a visceral nociceptive pathway within these tracts. [6]

The cell bodies of the first-order unipolar neurons lie in the dorsal root ganglia just outside the cord parenchyma. Impulses enter the cord and are carried ipsilaterally. Fibers travel rostrally in the dorsal columns to synapse in the nucleus gracilis and nucleus cuneatus in the caudal medulla.

The fasciculus gracilis lies medial to the cuneatus in the posterior cord and subserves leg sensation. The fasciculus cuneatus lies lateral to the gracilis in the posterior cord and subserves arm sensation.

Second-order neurons contribute to the arcuate fasciculus. They decussate and subsequently ascend in the contralateral medial lemniscus to synapse in the ventroposterolateral (VPL) nucleus of the thalamus.

Third-order neurons travel in the posterior part of the posterior limb of the internal capsule to terminate in the primary and secondary somatosensory cortex (i.e., postcentral gyrus and/or Brodmann areas 1-3).

The lateral spinothalamic tract lies in the ventrolateral cord and carries pain, temperature, and crude touch sensation. Smaller, unipolar neurons in the dorsal root ganglia are the first-order neurons for this tract. Impulses from naked nerve endings travel in small, thinly myelinated (i.e., A delta and/or type II) and unmyelinated (i.e., C or type III) fibers, which funnel into the dorsolateral fasciculus (i.e., the tract of Lissauer). Each axon bifurcates into ascending and descending branches, which extend for 1-2 segments and then give off collateral branches, which synapse in the ipsilateral dorsal horn (laminae I-VI).

Neurons located at lamina II (i.e., substantia gelatinosa) seem to modulate the function of laminae III and IV, altering transmission from primary to secondary sensory systems. They receive projections from the brainstem reticular formation: periventricular and periaqueductal gray and nucleus raphe magnus.

The cell bodies of the second neuron are located in the marginal nucleus (lamina I) and proper sensory nucleus. Axons of second-order neurons cross in the ventral white commissure (just anterior to the central canal). They then ascend in the contralateral lateral spinothalamic tract to synapse in the VPL thalamic nucleus.

Fibers of the spinothalamic tract are somatotopically organized: sacral fibers are located laterally; lumbar, thoracic, and cervical fibers join medially.

Third-order neurons located at the VPL give rise to axons that travel in the posterior part of the posterior limb of the internal capsule to terminate in the primary and secondary somatosensory cortex.

An anterior spinothalamic tract ascends in the anterior and anterolateral funiculi. It originates mostly in lamina VII. Its fibers project to the periaqueductal gray matter and intralaminar thalamic nuclei. It carries light touch impulses; when lesioned, little or no disturbance in function is produced. Its collaterals also synapse in the medullary reticular formation.

Spinoreticular fibers also synapse in nearby areas, giving rise to multisynaptic reticulothalamic projections, which activate multiple areas of the cerebral cortex. These medial thalamic fibers are involved with arousal, attention, and motivational and affective aspects of pain perception.

Spinocerebellar tract

Dorsal spinocerebellar tracts lie in the lateral cord and run ipsilaterally toward the ipsilateral vermis of the anterior cerebellar lobe, entering through the inferior cerebellar peduncle. This tract arises from the nucleus dorsalis of Clarke, which forms a column of neurons in the medial part of lamina VII from C8 to L2. It receives afferents directly from the collaterals of the lumbosacral parts of the gracile tract. It carries nonconscious sensation of muscle position and tone from the lower extremities.

Similar impulses from the upper extremities run through the cuneate tract, synapsing directly into the accessory cuneate nucleus in the medulla. It then gives rise to the cuneocerebellar tract, which enters through the inferior cerebellar peduncle to reach the paravermis of the anterior cerebellar lobe.

A small, ventral spinocerebellar tract also exists in humans. It relays impulses about the status of the descending influences over the spinal cord motor neurons. Its neurons are scattered in the anterior horn and intermediate zone and decussate in the spinal cord. They enter the cerebellum through the superior cerebellar peduncle.

Propriospinal neuronal system

This system is responsible for the integration of different spinal cord segments during complex movement performance. It includes three groups of intraspinal neurons, as follows:

-

Long propriospinal neurons – They give rise to axons that ascend and descend in the anterior fasciculus proprius to all levels of the spinal cord. They influence medial motor neurons, subserving medial muscles bilaterally. Their role extends to forelimb-hindlimb coordination, as they link cervical and lumbar central pattern generators (CPGs) responsible for rhythmic locomotor activity. [7]

-

Intermediate propriospinal neurons – They have shorter axons, which run in the lateral part of the fasciculus proprius and modulate motor neurons that influence the activity of proximal limb muscles. They are involved in integrating sensory feedback with descending motor commands to refine movement patterns. [7]

-

Short propriospinal neurons – They are located only in the cervical and lumbosacral enlargements. Their axons travel through different segments in the lateral funiculus proprius and modulate more distal limb muscles.

-

Propriospinal neurons form part of the spinal locomotor CPGs, which generate rhythmic motor outputs for walking and running. Long ascending propriospinal neurons ensure synchronized limb movements during locomotion by connecting cervical and lumbar CPGs, while long descending propriospinal neurons contribute to postural stability and interlimb coordination. [8] Propriospinal neurons integrate sensory inputs from peripheral receptors with descending motor commands, enabling adaptive responses during movement. This integration is crucial for maintaining balance and adjusting motor output based on environmental demands. [7]

Autonomic pathways

Preganglionic sympathetic neurons are located in the intermediolateral cell column (lamina VII), which lies in the lateral aspect of the gray matter at levels T1-L3.

Preganglionic fibers pass through the ventral roots, spinal nerves, and white communicating rami, ending in the sympathetic paravertebral ganglia at different levels. They are cholinergic. Second-order neurons then reach the end organ and, in most cases, use norepinephrine as their neurotransmitter.

Sacral preganglionic neurons are located in and near the intermediolateral nucleus of S2-S4. They are cholinergic and emerge from the spinal cord, synapsing in the end organ ganglia. Postganglionic neurons are cholinergic and control defecation, urination, and erection.

Neural control of the urinary bladder

The urogenital tract is innervated by three groups of peripheral nerves: the sacral parasympathetic, lumbar sympathetic, and sacral somatic nerves.

Parasympathetic preganglionic neurons are located in the intermediolateral gray matter (laminae V-VII). Sacral parasympathetic pathways run through the pelvic nerves and are the major excitatory pathways to the urinary bladder. Parasympathetic activation leads to detrusor contraction via acetylcholine release, acting on muscarinic (M3) receptors on the detrusor muscle, facilitating bladder emptying. Nitric oxide (NO) released from parasympathetic nerve terminals also contributes to urethral smooth muscle relaxation during voiding. [9]

Sympathetic preganglionic neurons are located in the medial (lamina X) and lateral gray matter (laminae V-VII) of the rostral lumbar cord. Thoracolumbar sympathetic pathways come from the lumbar/sacral sympathetic ganglia; they inhibit the detrusor (beta-mediated) and excite the base of the bladder and urethra (alpha-mediated). Most importantly, they modulate the function of the parasympathetic ganglia (alpha-2 leads to inhibition and alpha-1 to facilitation).

Somatic efferent pathways innervate the urethral striated muscles and originate from a circumscribed lateral ventral horn region, known as Onuf's (or Onufrowicz) nucleus. These neurons travel via the pudendal nerve to innervate striated muscles of the external urethral sphincter. This allows voluntary control over micturition by contracting or relaxing the sphincter. [10]

A alpha and C afferent pathways initiate micturition. A alpha fibers exhibit graded response to passive distension, while C fibers have a much higher threshold, being activated by inflammation and noxious stimuli. Fullness of the bladder is detected by receptors in the bladder wall, which send impulses through the sacral parasympathetic nerves. Impulses reach the cortex through the spinothalamic tracts.

Sensation that micturition is imminent arises from receptors located at the bladder trigone and ascends in the dorsal column system.

The afferent signals are relayed to higher centers such as the PAG and pontine micturition center (PMC), which play critical roles in switching between storage and voiding phases. The spinothalamic and dorsal column systems transmit these sensory signals to cortical areas for conscious perception. The brainstem's PMC orchestrates micturition by coordinating detrusor contraction with urethral sphincter relaxation. During voiding the PMC activates parasympathetic outflow to contract the detrusor muscle. It inhibits sympathetic outflow, relaxing the internal urethral sphincter. It suppresses somatic efferent activity to relax the external urethral sphincter. Higher brain centers, including the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex, exert voluntary control over micturition by modulating PMC activity via inputs through the periaqueductal gray. [9, 11]

Urine is stored when the external urethral sphincter muscle (somatic) and the internal urethral sphincter muscle (sympathetic) are contracted and the detrusor muscle and sacral parasympathetic activity are inhibited through sympathetic mediation.

Sympathetic integrity is not essential for the performance of micturition. However, experimental evidence suggests that sympathetic input causes tonic inhibitory input to the bladder and excitatory input to the urethra. During micturition, descending pathways originating from the PMC inhibit external urethral sphincter activity, inhibit sympathetic outflow (inhibition of the vesico-sympathetic reflex), activate parasympathetic outflow to the bladder, and activate parasympathetic outflow to the urethra.

For patient education information, see Bladder Control Problems.

Innervation of the sexual organs

Parasympathetic pathways arising from the sacral spinal cord innervate the erectile tissue in the penis and clitoris; smooth muscle and glandular tissue in the prostate, urethra, seminal vesicles, vagina, and uterus; and blood vessels and secretory epithelia in various structures. These pathways travel via the pelvic splanchnic nerves to the inferior hypogastric plexus, providing essential autonomic regulation of sexual function. [1]

The most studied function has been penile erection, starting with the observation of Eckhard in 1863 that stimulation of the pelvic nerves leads to penile erection in several species.

Penile erection is primarily mediated by NO, a key neurotransmitter released by nonadrenergic, noncholinergic parasympathetic nerves. NO induces smooth muscle relaxation in the corpora cavernosa by activating guanylyl cyclase, leading to increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels. This results in vasodilation of penile blood vessels, increased blood flow into the cavernous spaces, and subsequent compression of subtunical veins against the tunica albuginea, creating a veno-occlusive mechanism that maintains rigidity. [12]

In women, similar mechanisms govern clitoral tumescence. However, clitoral engorgement is less rigid due to a thinner tunica albuginea surrounding the corpora cavernosa. Reflexogenic arousal, triggered by tactile stimulation of genitalia, involves afferent sensory input to the sacral spinal cord (S2-S4), which activates parasympathetic efferent pathways via the pelvic plexus and cavernous nerves. [12]

The integration of autonomic control involves both parasympathetic and sympathetic systems. While parasympathetic activation promotes erection through vasodilation and smooth muscle relaxation, sympathetic activity mediates detumescence via contraction of smooth muscles and reduction in arterial inflow. The thoracolumbar sympathetic outflow (T11-L2) also contributes to psychogenic erections by modulating vascular tone. [12]

Spinal Cord Vascular Supply

Arterial supply

The spinal cord is supplied by descending branches of the vertebral arteries (i.e., anterior spinal arteries) and multiple radicular arteries derived from segmental vessels.

Paired anterior spinal arteries unite to form a single descending vessel (i.e., anterior spinal artery), which enters the anterior median fissure of the spinal cord and supplies the anterior two thirds of the cord. It also supplies midline rami to the lower medulla. Like the basilar artery, it has smaller penetrating and circumferential branches.

Two posterior spinal arteries each supply the ipsilateral posterior one sixth of the cord (or combined, the posterior one third). They receive varied contribution from the posterior radicular arteries and form two longitudinal plexiform channels near the dorsal root entry zone.

Radicular arteries are derived from segmental vessels (e.g., ascending cervical, deep cervical, intercostal, lumbar, and sacral arteries) that pass the intervertebral foramina and give rise to anterior and posterior radicular arteries. Segmental radicular arteries supply blood to the roots, and segmental radiculospinal arteries supply the roots and the cord. Usually, a few large, segmental radiculospinal arteries are noted, including the artery of Adamkiewicz (or artery of the lumbar enlargement), which is larger than the others; it usually originates between T9 and T12 (in 75% of cases) and supplies the lower one third of the cord.

Where two anterior radicular arteries reach the same level of the spinal cord, a diamond-shaped arterial configuration develops. The distance between radicular arteries is greatest in the thoracic spinal segments; thus, occlusion of one thoracic radicular artery may seriously compromise the circulation. Therefore, the upper thoracic (T1-4) and L1 segments are particularly vulnerable to vascular insults.

Venous drainage

Veins draining the spinal cord have a distribution similar to that of the arteries. Anterior longitudinal trunks consist of anteromedian and anterolateral veins. Sulcal veins drain the anteromedian portions of the spinal cord. Anterolateral regions of the spinal cord drain into anterolateral veins. Posterior, longitudinal venous trunks drain the posterior funiculi. The internal vertebral venous plexuses (i.e., epidural venous plexuses) are located between the dura mater and the vertebral periosteum and consist of two or more anterior and posterior, longitudinal venous channels that are interconnected at many levels from the clivus to the sacral region.

At each intervertebral space are connections with thoracic, abdominal, and intercostal veins and external vertebral venous plexuses. These spinal veins have no valves, and blood passes directly into the systemic venous system. The continuity of this venous plexus with the prostatic plexus is probably the path along which prostatic neoplastic cells metastasize.

Developments in magnetic resonance angiography with fast contrast-enhanced techniques have enabled noninvasive imaging of normal and abnormal vessels of the spinal cord, including visualization of the Adamkiewicz artery and differentiation of arteries and veins. [13] These techniques will likely improve the diagnosis of several conditions associated with abnormalities of the arterial and venous spinal cord supply.

Classic Spinal Cord Syndromes

The classic syndromes of spinal cord injury are described here. In most instances, however, incomplete forms are far more common.

Complete spinal cord transection syndrome

In the acute phase, the classic syndrome of complete spinal cord transection at the high cervical level consists of the following:

-

Respiratory insufficiency

-

Quadriplegia

-

Upper and lower extremity areflexia

-

Anesthesia below the affected level

-

Neurogenic shock (hypotension without compensatory tachycardia)

-

Loss of rectal and bladder sphincter tone

-

Urinary and bowel retention leading to abdominal distention, ileus, and delayed gastric emptying

This constellation of symptoms is called spinal shock. [14] Horner syndrome (i.e., ipsilateral ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis) is also present with higher lesions because of interruption of the descending sympathetic pathways originating from the hypothalamus.

Patients experience problems with temperature regulation because of the sympathetic impairment, which leads to hypothermia.

Lower cervical level injury spares the respiratory muscles. High thoracic lesions lead to paraparesis instead of quadriparesis, but autonomic symptoms are still marked. In lower thoracic and lumbar lesions, hypotension is not present but urinary and bowel retention are.

In the subacute phase, the flaccidity of spinal shock is replaced by the return of intrinsic activity of spinal neurons, and spasticity develops. This usually happens in humans within three weeks of injury. However, the spinal shock phase may be prolonged by other medical complications, such as infections.

Quadriplegia and sensory loss below the level of injury persist, but spinal reflexes return. Because modulation from supraspinal centers is lost, hyperreflexia with increased tone and extensor plantar responses are noted. At any given level, with more extensive involvement of the anterior horn, flaccidity with loss of reflex activity and atrophy is present in a lower motor neuron pattern (as is common in diseases such as poliomyelitis).

Autonomic hyperreflexia

Autonomic hyperreflexia is also present in the subacute phase. Usually, the initial hypotension after high lesions resolves, although orthostatic hypotension persists. For lesions above the lumbosacral centers for bladder control, the initial urinary retention is replaced by the development of an automatic spastic bladder. Lower lesions lead to permanent atonic bladder (i.e., lower motor neuron pattern). [15]

Autonomic hyperreflexia in this phase is characterized by the massive firing of sympathetic neurons after distention, stimulation, or manipulation of the bladder and bowels. Cutaneous stimulation with painful or cold stimuli can also lead to massive sympathetic firing.

This is a life-threatening condition because blood pressure may increase as high as 300 mm Hg, leading to intracerebral hemorrhage, confusional states, and death. A response to the massive sympathetic discharge is generated at the brainstem level. However, interruption of descending projections to the spinal cord can prevent inhibition of the spinal cord sympathetic centers, which continue to fire inappropriately until the stimulus is removed. A vagal inhibitory reflex to the heart is generated, which leads to bradycardia and worsening symptoms.

Anterior cord syndrome

Anterior cord syndrome is typically observed with anterior spinal artery infarction and results in paralysis below the level of the lesion, with loss of pain and temperature sensation and relative sparing of touch, vibration, and position sense (because the posterior columns receive their primary blood supply from the posterior spinal arteries).

Central cord syndrome

Central cord syndrome is observed most often in syringomyelia, hydromyelia, and trauma. Hemorrhage and intramedullary tumors, such as central canal ependymoma, are other causes. Because central cord syndrome is more common in the cervical cord, the arms are often weak, with preservation of strength in the legs ("man-in-a-barrel syndrome"). Considerable recovery is common. This syndrome is associated with variable sensory and reflex deficits; often the most affected sensory modalities are pain and temperature because the lateral spinothalamic tract fibers cross just ventral to the central canal. This is sometimes referred to as dissociated sensory loss and is often present in a cape-like distribution.

Lateral extension can result in ipsilateral Horner syndrome (because of the involvement of the ciliospinal center), kyphoscoliosis (because of the involvement of the dorsomedian and ventromedian motor nuclei supplying the paraspinal muscles), and spastic paralysis (because of corticospinal tract involvement). Dorsal extension can result in ipsilateral position sense and vibratory loss due to the involvement of the dorsal column.

Brown-Séquard syndrome

Brown-Séquard syndrome may be considered equivalent to a hemicordectomy. Ipsilateral paralysis, loss of vibration and position sense below the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, and an extensor toe sign are all noted. Ipsilateral segmental anesthesia is also observed at the lesion level. Loss of pain and temperature is observed contralaterally below the level of the lesion (beginning perhaps 2-3 segments below). Brown-Séquard syndrome is most common after trauma. However, the full spectrum of this syndrome is rare.

Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndromes

Patients with lesions affecting only the cauda equina can present with a polyradiculopathy in the lumbosacral area, with pain, radicular sensory changes, asymmetrical lower motor neuron-type leg weakness, and sphincter dysfunction. This may be difficult to distinguish from plexus or nerve involvement. Lesions affecting only the conus medullaris cause early disturbance of bowel and bladder functions. Syndromes due to the involvement of the lower spinal cord, cauda equina, or conus have received more attention with advances in neuroimaging, especially in developing countries where helminthic infections may lead to spinal cord schistosomiasis. [16, 17] Involvement of conus medullaris is also an important feature of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. [18]

Radiculopathy syndromes

Patients with radicular involvement present with dermatomal sensory changes with dorsal root involvement and with myotomal weakness with ventral root involvement. In general, radicular pain (e.g., root distribution or shooting pain) increases with increased intraspinal pressure (e.g., coughing, sneezing, and the Valsalva maneuver).

-

Spine, anterior view.

-

Spine, lateral view.

-

Cervical spinal cord.

-

Sacral spinal cord.

-

Spinal cord cross-section, detailed anatomy.