Practice Essentials

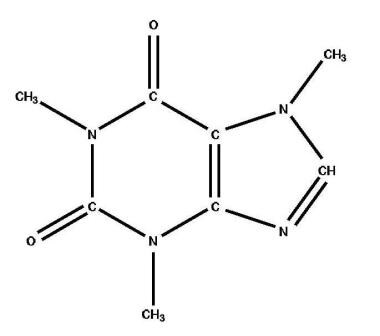

Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine; see the image below) is the most widely consumed stimulant drug in the world. [1] It is present in medications (prescribed and over-the-counter [OTC]), coffee, tea, soft drinks, energy shots, diet aids, herbal medicine, and chocolate. [2] Because caffeine overdoses, intentional or unintentional, are relatively common in the United States, physicians and other medical personnel must be aware of caffeine toxicity to recognize and treat it appropriately.

Signs and symptoms

When acute caffeine ingestion is suspected, the history should address the following:

-

Use of prescription medications or OTC drugs

-

Use of illicit drugs

-

Recent caffeine ingestion or recent behavior compatible with such ingestion

When ingested in excessive amounts for extended periods, caffeine produces a specific toxidrome (caffeinism), which consists primarily of the following features:

-

Central nervous system (CNS) - Headache, lightheadedness, anxiety, agitation, tremulousness, perioral and extremity tingling, confusion, psychosis, seizures

-

Cardiovascular - Palpitations or racing heart rate, chest pain

-

Gastrointestinal (GI) - Nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bowel incontinence, anorexia

CNS findings on physical examination include the following:

-

Anxiety, agitation

-

Tremors

-

Seizures

-

Altered mental status

-

Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat findings

-

Pupils that are dilated but reactive to light

The thyroid should be examined because thyrotoxicosis may mimic caffeine toxicity.

Cardiovascular findings on physical examination include the following:

-

Widened pulse pressure

-

Sinus tachycardia, dysrhythmias

-

Hypotension

-

Tachypnea

GI findings on physical examination include the following:

-

Vomiting

-

Abdominal cramping

-

Hyperactive bowel sounds

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

In hemodynamically stable patients with mild symptoms and a clear history of caffeine ingestion, no laboratory studies are indicated. Laboratory studies are indicated in patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms of caffeine toxicity. The following studies may be helpful:

-

Complete blood count (CBC)

-

Serum electrolyte, glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine concentrations

-

Routine screening for other potentially treatable toxins

-

Total creatine kinase (CK) concentrations

-

Dipstick urinalysis

-

Rapid urine drug screen

-

Serum ethanol concentrations and osmolality (in cases of unknown ingestion or suspected coingestion)

-

Serum pregnancy test

-

Thyroid studies

-

Arterial blood gas analysis

Serum caffeine concentration determinations do not influence management.

In hemodynamically stable patients with only mild symptoms, no diagnostic imaging is required. The following studies may be considered in particular circumstances:

-

Chest radiography - In patients with chest pain, fever, altered mental status, or respiratory complaints

-

Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning of the head - In patients with seizures or altered mental status despite initial resuscitation

Patients with chest pain, palpitations, tachycardia, or an irregular heart rhythm should be evaluated with electrocardiography (ECG) and telemetry monitoring.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Prehospital care is primarily supportive, and most cases resolve. Emergency management of more severe cases includes the following:

-

ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation)

-

Management of hypotension

-

Correction of dysrhythmias

-

Management of seizures (with benzodiazepines or barbiturates)

-

Correction of metabolic disturbances (hypokalemia, rhabdomyolysis, hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis)

-

Treatment of prolonged vomiting

-

Decontamination with activated charcoal, sorbitol, or both

-

In rare severe cases, hemoperfusion or hemodialysis

Consultations may include a regional poison control center, a medical toxicologist, or a psychiatrist (once the patient is medically stable). Medically unstable patients are admitted for the appropriate level of care, depending on the clinical presentation.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

A systematic review of caffeine consumption in healthy populations concluded that in adults, intake of up to 400 mg/day is not associated with overt adverse effects. Intakes of up to 300 mg/day in pregnant women and up to 2.5 mg/kg/day in children and adolescents are acceptable. [3]

Using the 2022 Kantar Worldpanel Enhanced Beverage Service survey, a report by Mitchell et al determined that at least one caffeinated beverage is consumed daily by about 69% of the US population aged 2 years or older. [4]

Sixty-nine percent of caffeine is ingested in coffee, with carbonated soft drinks, tea, and energy drinks making up the next highest contributors, at 15.4%, 8.8%, and 6.3%, respectively. [4]

Caffeine intake in US children and adolescents remained stable from 1999 to 2010, but sources of caffeine changed: the contribution of soda decreased from 62% to 38% while that of coffee increased from 10% to nearly 24% and energy drinks (which did not exist in 1999) increased to nearly 6%. [5] In a 2014 nationally representative cross-sectional survey, nearly two thirds of US adolescents aged 13-17 years reported using energy drinks, and 41% had done so in the past 3 months. [6]

In quantities found in food and beverages, caffeine is unlikely to cause acute medical problems; however, a changing market in which energy drinks are not subject to FDA regulatory standards has raised concerns over caffeine-related health problems.

In 1989, the FDA limited the amount of caffeine in OTC products to a maximum of 200 mg/dose. Caffeine is present in concentrated forms in OTC products such as alertness-promoting medications (eg, NoDoz, Vivarin), menstrual aids (eg, Midol), analgesics (eg, Excedrin, Anacin, BC Powder), and diet aids (eg, Dexatrim). Caffeine is also a component of prescription medications (eg, Fioricet, Cafergot) and herbal preparations. The ingestion of such concentrated sources of caffeine is the general cause of acute caffeine toxicity.

In cola beverages, caffeine is permitted by the FDA for flavor use at a 0.02% (0.2 mg/mL) concentration, equivalent to 20 mg in a 100-mL beverage or 71 mg in a 12-ounce beverage (Code of Federal Regulations, title 21, sec. 182.1180). [7] Because caffeine is not considered a nutrient, the FDA does not require manufacturers to label the amount of caffeine present in food and beverages, although caffeine must be listed as an ingredient if the manufacturer adds it to their product. [8]

More than 97% of caffeine consumed by adults and teenagers comes from beverages, including coffee, tea, cola products, and energy drinks. [9] Unlike cola beverages, energy drinks and shots are typically classified as dietary supplements; thus, individuals who consume these products are likely unaware of how much caffeine they are actually consuming. [8]

See the table below.

Table 1. Reported Caffeine Content of Common Foods, Beverages, and Drugs [10, 11, 12] (Open Table in a new window)

Item |

Amount |

Caffeine Content, mg |

| Milk chocolate | 1 oz | 6 |

| Dark chocolate (45-60% cacao) | 1 oz | 12 |

| Brewed green tea | 8 oz | 20 |

Brewed black tea, generic |

8 oz |

45-74 |

| Coca-Cola Classic | 12 oz | 35 |

| Pepsi cola | 12 oz | 38 |

| Mountain Dew | 12 oz | 54 |

| Brewed coffee, generic | 8 oz | 57 |

| Espresso | 1 oz | 40 |

Starbucks Tall Americano |

16 oz |

330 |

Fiorinal/Fioricet |

1 tablet |

40 |

Midol |

1 capsule | 60 |

| Excedrin pain reliever | 1 tablet | 65 |

| Dexatrim Natural | 1 tablet | 80 |

| No Doz | 1 tablet | 100 |

| Vivarin | 1 tablet | 200 |

| Jolt cola | 12 oz | 80 |

Red Bull Regular |

8.4 oz |

80 |

| Monster energy drink | 16 oz | 80 |

Jolt caffeine energy gum |

2 pieces | 100 |

Rockstar |

16 oz |

160 |

Monster Energy |

16 oz |

160 |

| Alani Nu | 12 oz | 200 |

| 5 Hour Energy | 1.9 oz | 200 |

| Ripped Fuel Extreme Ephedra Free | 2 capsules | 220 |

| Taiwanese Milk Tea | 24 oz | 226 |

NOS |

16 oz |

160 |

| Bang Energy | 16 oz | 300 |

The caffeine content of dietary supplements is virtually unregulated by the FDA. Prior to the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, dietary supplements were subject to the same regulatory requirements as other foods; however, after DSHEA, the safety of dietary supplements became the sole responsibility of manufacturers. Consequentially, there are no limitations on the amount of caffeine in dietary supplements and manufacturers are not required to list the caffeine content of their products.

In 2018, the FDA issued a new guidance regulating the sale of "bulk quantities" (packages containing enough powder or liquid for thousands of recommended servings) of pure or highly concentrated caffeine in powder or liquid forms sold directly to consumers. However the FDA did not address preexisting beverages. [13]

The rising popularity of caffeinated energy drinks has raised new concerns about their impact on public health. As illustrated above, energy drinks contain substantially more caffeine than conventional cola beverages, with caffeine content ranging from 75-300 mg per serving. Many also have caffeine-containing ingredients such as guarana, kola nut, or yerba mate. Consequentially, they may contain more caffeine than reported in Table 1 above. [14] These energy drinks are also sold in larger sizes (16-23.5 fl oz). It is not uncommon for individuals to consume multiple caffeinated beverages over the course of a day.

Caffeine has differing CNS, cardiovascular, and metabolic effects based on the quantity ingested. Average doses of caffeine (85-250 mg, the equivalent of 1-3 cups of coffee) may result in feelings of alertness, decreased fatigue, and increased focus or attention. High doses (250-500 mg) can result in restlessness, nervousness, insomnia, and tremors. As the dosing increases, caffeine can eventually cause hyperadrenergic symptoms resulting in seizures and cardiovascular instability.

Although most cases of caffeine toxicity are relatively mild in the United States, physicians and other medical personnel must be aware of the signs of caffeine toxicity to recognize and treat it appropriately. Most severe cases of toxicity are found in conjunction with other substances (eg, alcohol, analgesics, illicit drugs).

Pathophysiology

Caffeine, a methylxanthine, is closely related to theophylline. Caffeine is rapidly and completely absorbed from the GI tract; it is detectable in the plasma 5 minutes after ingestion, with peak plasma levels occurring in 30-60 minutes. The volume of distribution in adults is approximately 0.5 L/kg.

Caffeine is primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) oxidase system in the liver. The plasma half-life of caffeine varies considerably from person to person, with an average half-life of 5-8 hours in healthy, nonsmoking adults. Caffeine clearance is accelerated in smokers; clearance is slowed in pregnancy, in liver disease, and in the presence of some CYP inhibitors (eg, cimetidine, quinolones, erythromycin). In addition, the hepatic enzyme system responsible for caffeine metabolism can become saturated at high levels, resulting in a marked increase in serum concentration with small additional doses.

Various mechanisms mediate the effects of caffeine in the human body. Caffeine directly stimulates respiratory and vasomotor centers of the brain and acts as an adenosine antagonist, resulting in peripheral vasodilatation and CNS stimulation. Caffeine is a potent releaser of catecholamines (norepinephrine and, to a lesser extent, epinephrine) that increases cardiac chronotropic and inotropic activity, bronchodilation, and peripheral vasodilation. Caffeine is also a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. However, because extremely high concentrations of caffeine are required to inhibit this enzyme, whether this effect contributes to the clinical effects of caffeine in vivo is unknown.

In addition to its cardiovascular effects, caffeine induces a number of metabolic changes, including hyperglycemia (by stimulating gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis), increased renal filtration, ketosis, and hypokalemia. Caffeine is a potent stimulator of gastric acid secretion and GI motility.

Classic drugs of abuse lead to specific increases in cerebral functional activity and dopamine release in the shell of the nucleus accumbens (the key neural structure for reward, motivation, and addiction). In contrast, caffeine at doses reflecting daily human consumption does not induce a release of dopamine in the shell of the nucleus accumbens but leads to a release of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex, which is consistent with its reinforcing properties.

Furthermore, caffeine increases glucose utilization in the shell of the nucleus accumbens only at high concentrations; this, in turn, nonspecifically stimulates most brain structures and thus likely reflects the side effects linked to high caffeine ingestion alone. Moreover, this dose is 5-10 times higher than the dose necessary to stimulate the caudate nucleus (extrapyramidal motor system) and the neural structures regulating the sleep-wake cycle, the two functions that are most sensitive to caffeine.

Thus, although caffeine fulfills some of the criteria for drug dependence and shares with amphetamine and cocaine a certain specificity of action on the cerebral dopaminergic system, it does not act on the dopaminergic structures related to reward, motivation, and addiction.

Every exposure to caffeine can produce cerebral stimulant effects. This is especially true in the areas that control locomotor activity (eg, caudate nucleus) and structures involved in the sleep-wake cycle (eg, locus coeruleus, raphe nuclei, and reticular formation). In humans, as indicated above, sleep seems to be the physiologic function most sensitive to the effects of caffeine. Generally, more than 200 mg of caffeine is required to affect sleep significantly. Caffeine has been shown to prolong sleep latency and shorten total sleep duration while preserving the dream phases.

Death from caffeine toxicity is rare, but it has been reported due to dysrhythmias, seizures, and aspiration of emesis. Oral doses of caffeine greater than 10 g can be fatal in adults. [15] A daily intake of up to 400 mg—about two to three 12-ounce cups of coffee—is considered safe for adults, while 200 mg is considered safe for pregnant women, and a single dose in adults should not exceed 200 mg. [16, 17] Caffeine-containing drinks should be avoided for children younger than age 2 years. [16] Complicating the calculation of caffeine intake from coffee is the wide variation in serving size and the difference in caffeine content with different brewing methods; in a Polish study, the caffeine content of a serving of the coffees tested ranged from 12.8 mg to 309.4 mg. [18]

Etiology

Chronic toxicity is generally encountered in people who have ingested higher doses of caffeine-containing compounds (alone or in combination) for various reasons. Patients may be unaware that some products contain caffeine or that high doses of caffeine can be harmful. Patients may ingest caffeine-containing analgesics for headaches, OTC caffeine-containing medications for dieting, or OTC medications for improving alertness while studying or working. In addition, people may drink caffeine in beverages such as coffee, tea, soft drinks, [19] or energy drinks or take caffeine in herbal preparations. [20]

Considerations include the following:

-

Acute toxicity can occur after intentional or unintentional ingestion; OTC alertness-promoting medications are often implicated in intentional overdoses

-

Certain medications, such as cytochrome inhibitors (eg, cimetidine) and oral contraceptives, impair caffeine metabolism [21]

-

Caffeine clearance is reduced in patients with chronic liver disease, in pregnant women, and in infants

-

Caffeine clearance is increased in smokers. With smoking cessation, serum caffeine concentrations can double even if caffeine consumption remains stable

Epidemiology

United States

Caffeine poisoning is a relatively common toxicologic emergency in the United States. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reported a jump in the number of emergency department visits involving energy drinks, increasing roughly 10-fold from 2005 (1128 visits) to 2008 and 2009 (16,053 and 13,114 visits, respectively). More than half of the visits made by patients age 18-25 years involved the combination of energy drinks with alcohol or other drugs. [22] Between 2007 and 2011 the number of energy drink–related visits to emergency departments doubled. [23]

The 2023 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System® (NPDS) from America's Poison Centers®: 41st Annual Report, recorded 1385 single exposures to caffeine from energy drinks with caffeine from any source (including guarana, kola nut, tea, etc), with eight major outcomes and no deaths. The report also recorded 650 single exposures from energy drinks with caffeine only, with no major outcomes or deaths. Under the heading “Miscellaneous Stimulants and Street Drugs,” the report recorded 2665 single caffeine exposures, with 22 major outcomes and two deaths. [24]

Caffeinated alcoholic beverages were a public health concern because caffeine can mask some sensory cues that people might normally rely on to determine their level of intoxication. The FDA banned their sales in 2010. [8] In spite of the ban, mixing alcohol with energy drinks is still common practice and popular. In 2015, 13.0% of students in grades 8, 10, and 12 and 33.5% of young adults aged 19 to 28 reported consuming alcohol mixed with energy drinks at least once in the past year. Furthermore, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that people who mix alcohol with energy drinks are more likely to binge drink. [25] It is very important for the physician to inquire about co-ingestion of caffeine-containing drinks when obtaining a history for possible drug overdose or alcohol poisoning.

Race-, Sex- and Age-related Variance

Caffeine is the most commonly used drug in the world, and its use is prevalent in essentially all races and ethnic groups. [1] No scientific data have demonstrated that the outcomes of caffeine exposure differ on the basis of race or sex. [26]

According to the aforementioned study by Mitchell et al, caffeine consumers in the United States drink 210 mg of caffeine per day, with persons aged 50-64 years accounting for the highest amount (246 mg/day). Children aged 2-5 years have the lowest intake, at 42 mg/day. [4]

Whether or not the effects of caffeine on adults can be generalized to children is unclear; however, studies suggest that children are differently affected by caffeine. One study comparing the effects of caffeine in men and boys found that the same body weight–based dose of caffeine raised blood pressure in both groups but decreased resting heart rate in boys only. They also found that boys exhibited increased motor activity and speech rates and decreased reaction time compared with men. [27]

Another study found that an intake of 5 mg/kg body weight leads to elevated blood pressure and lower heart rate, without concomitant changes in energy metabolism, in children aged 9-11 years. This amounts to 160 mg caffeine/day in a 10-year-old child weighing 30 kg, which is equivalent to the caffeine content of a single 16-oz Monster or Rockstar energy drink. [28]

A study by Kristjansson et al of middle school students indicated that consumption of more than 100 mg/day of caffeine is associated with reduction in self-control and an increase in problem behavior, in these adolescents, as observed by the students’ homeroom teachers. [29]

Additional age-related concerns arise from the fact that many energy drinks are marketed toward youth and youth-related activities, such as extreme sports. Students and athletes often drink them to enhance performance. A survey of 496 college students found that 51% of those surveyed drank more than one energy drink per month, with the majority of students drinking several energy drinks per week. The main impetus was the desire for increased energy and concentration, with the most common complaint being insufficient sleep or a disruption in their regular sleep cycles. [30]

Prognosis

Rare cases of caffeine-induced ventricular dysrhythmias refractory to advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocols are reported. In general, however, the prognosis is excellent for patients with caffeine toxicity who reach a medical facility and who can be supported through the acute phase.

Death is an uncommon result of caffeine poisoning but may be due to caffeine-related dysrhythmias, seizures, and aspiration of emesis. Oral doses of caffeine greater than 10 g can be fatal in adults. [15]

The AAPC reported one death related to caffeine in 2022. [31] The FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) Adverse Event Reporting System (CAERS) reported 29 deaths related solely to Monster, 5-Hour Energy, and Rockstar energy drinks from 2004-2013. [32] A review of CAERS data from January 1, 2014 to June 29, 2018 on adverse events from caffeinated products found 15 deaths from energy products; nine from preworkout products; 15 from weight loss products; and one from coffee, tea, or soda. [33]

Patient Education

Patients may be unaware of the caffeine content of various products (eg, energy drinks, herbal medications, alertness-promoting medications) or of the ill effects related to these medications. Patients in the emergency department or in other health-care settings who appear to have effects related to caffeine ingestion should be counseled to limit their caffeine intake and to avoid concentrated sources of caffeine.

-

Caffeine content of various foods, beverages, medications, and supplements. Caffeine content is approximate for brewed beverages and chocolate).

-

Chemical structure of caffeine.