Practice Essentials

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare but critical condition characterized by hemorrhagic infarction of the pituitary gland or tumor. [1] Patients typically present with an abrupt onset of severe headache, neck stiffness, visual disturbances, and oculomotor palsies. The development of edema from the hemorrhage can lead to neurological signs such as somnolence or coma due to compression of the adjacent structures like the hypothalamus. There also may be a rapid decline in pituitary function resulting in symptoms of hypopituitarism, such as vascular collapse due to deficient levels of ACTH and cortisol.

Diagnosis is based on a thorough clinical history, comprehensive physical examination, and neuroimaging findings that typically show evidence of hemorrhage. Management of pituitary apoplexy may involve a multidisciplinary approach, ranging from conservative measures to urgent surgical intervention through the trans-sphenoidal route. Timely recognition and appropriate treatment are essential for optimizing patient outcomes in this potentially life-threatening condition.

Background

The word apoplexy is defined as a sudden neurologic impairment, usually due to a vascular process. Pituitary apoplexy is characterized by a sudden onset of headache, visual symptoms, altered mental status, and hormonal dysfunction due to acute hemorrhage or infarction of a pituitary gland. [1] An existing pituitary adenoma usually is present. The visual symptoms may include both visual acuity impairment and visual field impairment from involvement of the optic nerve or chiasm, and also may include ocular motility dysfunction from involvement of the cranial nerves traversing the cavernous sinus. [2] It is important to note that pituitary apoplexy may be divided into hemorrhagic or ischemic, each with unique neuroimaging findings, and some patients have elements of both.

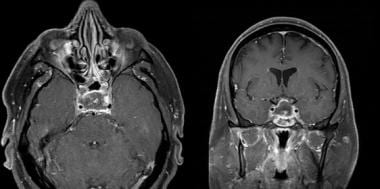

Enhanced T1-weighted axial and coronal MRI showing a large pituitary tumor that has recently undergone ischemic apoplexy showing a necrotic (hypointense) center and ring of gadolinium enhancement (hyperintense), ie, the "pituitary ring sign." There is a small area of hemorrhagic blush in the center of the necrosis.

Enhanced T1-weighted axial and coronal MRI showing a large pituitary tumor that has recently undergone ischemic apoplexy showing a necrotic (hypointense) center and ring of gadolinium enhancement (hyperintense), ie, the "pituitary ring sign." There is a small area of hemorrhagic blush in the center of the necrosis.

Pathophysiology

Pituitary apoplexy stems from an acute expansion of a pituitary adenoma or, less commonly, in a nonadenomatous gland from infarction or hemorrhage. The anterior pituitary gland is perfused by its portal venous system, which passes down the hypophyseal stalk. This unusual vascular supply likely contributes to frequency of pituitary apoplexy. It is more common in macroadenomas and nonfunctioning adenomas, and it rarely has been reported in microadenomas. [3]

Some postulate that a gradually enlarging pituitary tumor becomes impacted at the diaphragmatic notch, compressing and distorting the hypophyseal stalk and its vascular supply. This deprives the anterior pituitary gland and the tumor itself of its vascular supply, apoplectically causing ischemia and subsequent necrosis.

Another theory stipulates that rapid expansion of the tumor outstrips its vascular supply, resulting in ischemia and necrosis. This explanation is doubtful, since most tumors that undergo apoplexy are slow growing.

Epidemiology

Frequency

International

Pituitary apoplexy results in an estimated 1.5-27.7% of cases of pituitary adenoma, although the figure probably is closer to 10%.

Mohr and Hardy reviewed hospital records of 664 patients who had surgery for pituitary adenomas. [4] Typical symptomatic pituitary apoplexy occurred in only 0.6% of patients with significant hemorrhagic and necrotic changes in 9.5% of surgical specimens.

Frequency of intratumoral hemorrhage increases to 26% if using only MRI criteria without clinical evidence of apoplexy. However, hemorrhagic pituitary apoplexy may be fatal. Kurisu et al described a 68-year-old man who developed pituitary apoplexy resulting in massive intracerebral hemorrhage and death 1 month later. [5]

Sex

Pituitary apoplexy has a male-to-female ratio of 2:1.

Age

The usual age range is 37-57 years. Pediatric pituitary apoplexy has been described. [6]

Prognosis

Pituitary apoplexy can be a life-threatening condition, and it is not easily diagnosed or treated. When appropriately managed, visual symptoms often improve, but endocrinologic function may remain compromised. [7]

Patient Education

Educate patients about the disorder and the complications that can arise from its treatment.

-

Enhanced coronal CT showing large pituitary tumor with a "snowman" configuration and heterogeneous density (mixed signal) within the tumor indicative of pituitary apoplexy. Hemorrhage was confirmed at surgery.

-

Enhanced axial and coronal T1-weighted MRI of a typical large pituitary tumor with a "snowman" configuration (coronal) and marked enhancement with contrast. This tumor has not undergone apoplexy.

-

Enhanced T1-weighted axial and coronal MRI showing a large pituitary tumor that has recently undergone ischemic apoplexy showing a necrotic (hypointense) center and ring of gadolinium enhancement (hyperintense), ie, the "pituitary ring sign." There is a small area of hemorrhagic blush in the center of the necrosis.

-

Automated visual field showing a bitemporal field defect due to compression of the optic chiasm from below.

-

Post-contrast sagittal T1-weighted scan shows sphenoid sinus roof mucosal thickening. The yellow arrow shows the “pituitary ring sign,” while the white arrow shows sphenoid sinus roof mucosal thickening. Courtesy of Taylor & Francis (Vaphiades MS. Pituitary Ring Sign Plus Sphenoid Sinus Mucosal Thickening: Neuroimaging Signs of Pituitary Apoplexy. Neuroophthalmology. 2017 Dec. 41 (6):306-309. Online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5764063/.).