Practice Essentials

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited disorders characterized by progressive peripheral vision loss and night vision difficulties (nyctalopia) that can lead to central vision loss.

Signs and symptoms

Presenting signs and symptoms of RP vary, but the classic ones include the following:

-

Nyctalopia (night blindness): Hallmark; most commonly the earliest symptom in RP

-

Visual loss, usually peripheral; in advanced cases, central visual loss

-

Photopsia (seeing flashes of light)

A careful family history with pedigree and possible examination of family members can be useful. In addition, a drug history is essential to rule out phenothiazine/thioridazine toxicity.

Diagnosis

Because RP is a collection of many inherited diseases, significant variability exists in the physical findings. Ocular examination involves assessment of visual acuity and pupillary reaction, as well as anterior segment, retinal, and funduscopic evaluation.

Systemic examination for RP can be helpful to rule out syndromic RP, which are conditions that have pigmentary retinopathy and mimic RP, such as the following:

-

Syndromes associated with RP and hearing loss: Usher syndrome, [1] Waardenburg syndrome, Alport syndrome, Refsum disease

-

Kearns-Sayre syndrome: External ophthalmoplegia, lid ptosis, heart block, and pigmentary retinopathy

-

Abetalipoproteinemia: Fat malabsorption, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, spinocerebellar degeneration, and pigmentary retinal degeneration

-

Mucopolysaccharidoses (eg, Hurler syndrome, Scheie syndrome, Sanfilippo syndrome): Can be affected with pigmentary retinopathy

-

Bardet-Biedl syndrome: Polydactyly, truncal obesity, kidney dysfunction, short stature, and pigmentary retinopathy

-

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: Dementia, seizures, and pigmentary retinopathy; infantile form is known as Jansky-Bielschowsky disease, juvenile form is Vogt-Spielmeyer-Batten disease, and adult form is Kufs syndrome

Testing

The following laboratory tests are useful in excluding masquerading diseases or in detecting conditions that are associated with RP:

-

Infectious studies for syphilis (VDRL, FTA-ABS), toxoplasmosis (when suspected; serum IgG)

-

Inherited/syndromic disease studies for Refsum disease (serum phytanic acid in the presence of other neurologic abnormalities), gyrate atrophy (ornithine levels), Kearns-Sayre syndrome (ECG to help rule out heart block), and abetalipoproteinemia (lipid profile with possible protein electrophoresis)

-

Neoplasm related studies for antiretinal antibodies (particularly antirecoverin antibodies), especially in cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR) or in severe RP

Other studies that may be helpful include the following:

-

Electroretinogram (ERG): Most critical diagnostic test for RP

-

Electro-oculogram (EOG): Not helpful in diagnosing RP, but central macular changes, normal ERG findings, and abnormal EOG findings suggest Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (Best disease)

-

Formal visual field testing: Most useful measure for ongoing follow-up care of patients with RP; Goldmann (kinetic) perimetry is recommended

-

Color testing: Commonly, mild blue-yellow axis color defects, although most patients with RP do not clinically complain of major difficulty with color perception

-

Dark adaptation study: Disproportionately reduced contrast sensitivity relative to visual acuity in RP; bright-light sensitivity

-

Genetic subtyping: Definitive test for diagnosis to identify the particular defect

Imaging tests

Fluorescein angiography is rarely useful in diagnosing RP; however, the presence of cystoid macular edema can be confirmed by this test. Likewise, although optical coherence tomography (OCT) is not useful in helping to establish a diagnosis of RP, this imaging study can be helpful to document the extent and/or presence of cystoid macular edema.

Procedures

Biopsy for histologic examination in patients with RP is not clinically helpful, owing to the general good health of these patients and the chronic nature of the disease. Generally, specimens are obtained only on chronically atrophic retinas.

Management

There is no cure for RP; therefore, therapies are limited. Nonetheless, it is essential to help patients maximize the vision they do have with refraction and low-vision evaluation.

Pharmacotherapy

Medications sometimes used in the management of RP include the following:

-

Supplements: (eg, Lutein, Zeaxanthin, Omega-3 Fatty Acids)

-

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg, acetazolamide, methazolamide, dorzolamide)

-

Triamcinolone, dexamethasone

The following are medications with potential adverse effects in RP:

-

Isotretinoin (Accutane)

-

Sildenafil (Viagra)

-

High-dose vitamin E

Surgery

Surgical management of RP generally involves cataract extraction; however, following FDA approval in February 2013 for the first retinal implant in adults with severe cases of RP, implantation of this device may become a viable treatment option. [2]

Investigational procedures with potential in managing RP include the following:

-

Surgical placement of growth factors

-

Transplantation of retinal or retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) tissue

-

Placement of retinal prosthesis or phototransducing chip

-

Gene therapy (eg, voretigene neparvovec)

Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited disorders characterized by progressive peripheral vision loss and night vision difficulties (nyctalopia) that can lead to central vision loss.

With advances in molecular research, it is now known that RP constitutes many retinal dystrophies and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) dystrophies caused by molecular defects in more than 40 different genes for isolated RP and more than 50 different genes for syndromic RP. Not only is the genotype heterogeneous, but patients with the same mutation can phenotypically have different disease manifestations. In this article, the clinical manifestations for diagnosis, the new molecular understandings of the pathogenesis, and the latest therapeutic options for patients are reviewed.

RP can be passed on by all types of inheritance: approximately 20% of RP is autosomal dominant (ADRP), 20% is autosomal recessive (ARRP), and 10% is X linked (XLRP), whereas the remaining 50% is found in patients without any known affected relatives. RP is most commonly found in isolation, but it can be associated with systemic disease. The most common systemic association is hearing loss (up to 30% of patients). Many of these patients are diagnosed with Usher syndrome. Other systemic conditions also demonstrate retinal changes identical to RP.

RP is a misnomer, as the word retinitis implies an inflammatory response, which has not been found to be a predominant feature of this condition. As molecular understanding increases, RP will be further characterized by the specific protein/genetic defect. This characterization will have increasing importance in the determination of a prognosis and will likely allow clinicians to use gene-targeted therapies.

Pathophysiology

RP is typically thought of as a rod-cone dystrophy in which the genetic defects cause cell death (apoptosis), predominantly in the rod photoreceptors; less commonly, the genetic defects affect the RPE and cone photoreceptors. [3] RP has significant phenotypic variation, as there are many different genes that lead to a diagnosis of RP, and patients with the same genetic mutation can present with very different retinal findings.

Histopathologic changes in RP have been well documented, and, more recently, specific histologic changes associated with certain gene mutations are being reported. The final common pathway remains photoreceptor cell death by apoptosis. The first histologic change found in the photoreceptors is shortening of the rod outer segments. The outer segments progressively shorten, followed by loss of the rod photoreceptor. This occurs most significantly in the mid periphery of the retina. These regions of the retina reflect the cell apoptosis by having decreased nuclei in the outer nuclear layer. In many cases, the degeneration tends to be worse in the inferior retina, thereby suggesting a role for light exposure.

The final common pathway in RP is typically death of the rod photoreceptors that leads to vision loss. As rods are most densely found in the midperipheral retina, cell loss in this area tends to lead to peripheral vision loss and night vision loss. How a gene mutation leads to slow progressive rod photoreceptor death can occur by many paths, as illustrated by the fact that so many different mutations can lead to a similar clinical picture.

Cone photoreceptor death occurs in a similar manner to rod apoptosis with shortening of the outer segments followed by cell loss. This can occur early or late in the various forms of RP.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

The prevalence of typical RP is reported to be approximately 1 in 4000 in the United States. The carrier state is believed to be approximately 1 in 100. The highest reported frequency of occurrence for RP is among the Navajo Indians at 1 in 1878.

International

Worldwide prevalence of RP is approximately 1 in 5000. The frequency of occurrence for RP has been reported to be as low as 1 in 7000 in Switzerland.

Mortality/Morbidity

A multicenter population study by Grover et al of patients with RP who were at least 45 years or older found the following findings: 52% had 20/40 or better vision in at least one eye, 25% had 20/200 or worse vision, and 0.5% had no light perception. [4]

Sex

Usually, no sexual predilection exists. X-linked RP is expressed only in males; therefore, because of these X-linked varieties, men may be affected slightly more than women.

Age

The age of onset can vary. RP usually is diagnosed in young adulthood, although it can present anywhere from infancy to the mid 30s to 50s.

-

Usher syndrome with typical retinitis pigmentosa appearance.

-

Choroideremia.

-

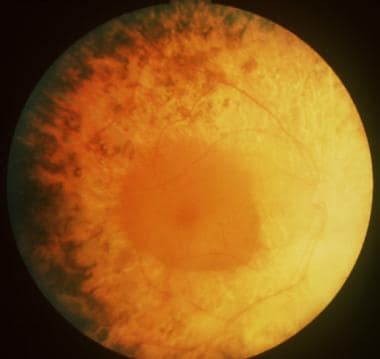

Bull's eye maculopathy seen in cone dystrophy.

-

Polydactyly seen in Bardet-Biedl syndrome (associated with retinitis pigmentosa).

-

Cone dystrophy.

-

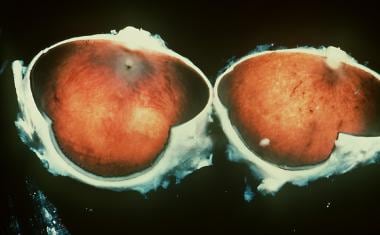

Gross pathology of an eye in a man with retinitis pigmentosa.

-

Leber congenital amaurosis.

-

Female carrier of choroideremia.

-

Representative electroretinograms of patients with healthy eyes, rod-cone dystrophy, and congenital stationary night blindness. Courtesy of Dr. Nusinowitz, Jules Stein Eye Institute.

-

Representative electroretinograms of patients with healthy eyes and X-linked retinoschisis. Courtesy of Dr. Nusinowitz, Jules Stein Eye Institute.

-

Retinitis pigmentosa pigmentation pattern demonstrated with ultrawide fundus imaging using the scanning laser ophthalmoscope (Optomap; Optos PLC, Dunfermline, Scotland, United Kingdom).

-

Fellow eye of same patient as in the image above, again demonstrating a typical retinitis pigmentosa pigmentation pattern demonstrated with ultrawide fundus imaging using the scanning laser ophthalmoscope (Optomap; Optos PLC, Dunfermline, Scotland, United Kingdom).

-

Higher resolution image of typical bone spicule formation.

-

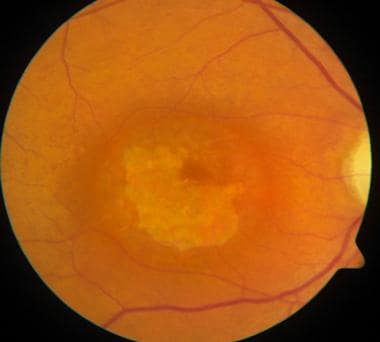

Cone dystrophy demonstrating typical central macular atrophy found in this condition.

-

Retinitis pigmentosa, rubella, a history of retinal detachment, and syphilis all may result in a hyperpigmented retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) with bone spicule appearance, restricted visual field and/or poor vision, and atrophic vessels.

-

Retinitis pigmentosa progresses over decades. Associated cataract also is relevant, as seen in this image.

-

Pigmentary changes are not always seen in retinitis pigmentosa but frequently are observed, as in this patient with Alström disease.

-

Genetic screening may be helpful in identifying patients who are at risk, in counseling, and in directing treatment as new knowledge is acquired. Some varieties of retinitis pigmentosa may have increased vulnerability to environmental hazards; for example, one might avoid light exposure in some rhodopsin mutations or sildenafil in phosphodiesterase mutations. Patients with retinitis pigmentosa may have other findings. This patient with Alström disease shows acanthosis.