Overview

The first association between a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotype and inflammatory disease was discovered in 1972 between HLA-B27 and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Since then, more than 100 links have been found between HLA haplotypes and ophthalmic and systemic diseases. [1] Most notable are AS, reactive arthritis (RA, previously referred to as Reiter syndrome), Behçet's disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and psoriatic arthritis (PA). These conditions are referred to as “seronegative spondyloarthropathies,” reflecting the absence of rheumatoid factor. [2]

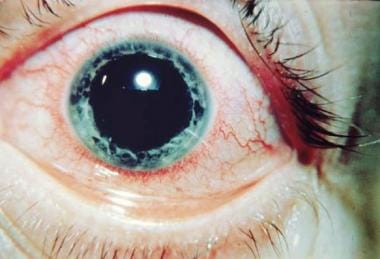

In ophthalmology, HLA haplotypes are associated with uveitis. Acute anterior uveitis (AAU), as depicted in Figure 1, may occur as a distinct clinical entity or in conjunction with a seronegative spondyloarthropathy. [3] Of patients with uveitis, 19-88% have the HLA-B27 phenotype.

Figure 1. Acute anterior uveitis in AS. The perilimbal erythema or “ciliary flush” is typical of inflammation in the anterior segment. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Figure 1. Acute anterior uveitis in AS. The perilimbal erythema or “ciliary flush” is typical of inflammation in the anterior segment. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Prevalence of the HLA-B27 haplotype varies between populations. In the United States, it is estimated at 6.1%, with rates estimated at 7.5% among non-Hispanic Whites and 3.5% across all other groups in the United States combined. The prevalence among Mexican Americans is 4.6%. [4] Among more isolated populations, HLA-B27 is non-existent in Australian Aborigines, 50% in Haida Indians and 34% in Russian Chukotka Natives. [5, 6] Of patients with AAU, 50-60% may be HLA-B27 positive. Both racial background and national origin affect this incidence rate. The frequency of HLA-B27-associated AAU is lowest in Blacks, intermediate in Asians, and highest in Whites. [10] An HLA disease association is defined as a statistically increased frequency of the haplotype in individuals with the disease compared to individuals without the disease. HLA-B27 positive individuals have an 87-fold increase in their relative risk of developing AS compared with HLA-B27 negative individuals.

Pathophysiology

The HLA system is genetically encoded in humans by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) which plays a determining role in immunity and self-recognition. [7] Three classes of gene products are encoded within the small region of the MHC. Class I MHC molecules are present on all nucleated cells, including HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C, and serve as the antigen-presenting platform for CD8 or suppressor T cells. Class II MHC molecules, including HLA-B subtypes, serve as the antigen-presenting cells for CD4 or helper T cells. Macrophages and dendritic cells are the important class II antigen-presenting cells. Class I and II molecules allow antigen presentation to specific T-cell receptors via a specific groove in its tertiary structure. Class III MHC molecules include several proteins with other immune functions, such as cytokines, heat shock proteins, and parts of the complement system.

The role of HLA-B27 in inflammatory disease is not precisely understood; however, it is generally accepted that pathologic responses occur following inappropriate binding of host or environmental peptides to class I and II MHC. The oldest theory is molecular mimicry, in which a normal immune response against a peptide from an infectious pathogen is erroneously directed against HLA-B27 due to epitome similarities between HLA-B27 and the infectious agent. At least two causative host peptides have been identified in patients with AS, supporting this hypothesis. Multiple T cell clones sensitized to HLA-B27-presented microbial and self-peptides have been discovered. These clones have been identified in the blood and synovial tissue of patients with AAU and AS, supporting this. [32]

A second theory, the misfolding hypothesis, is based on a peculiar biochemical property of the HLA-B27 molecule. Unfolded HLA-B27 proteins accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum, triggering an inflammatory response called the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response (ERUPR). As a result, interleukin 23 (IL-23) is released and activates an inflammatory response via interleukin-17+ T lymphocytes.

Another potential inflammatory mechanism of HLA-B27 is called the HLA-B27 heavy chain homodimer hypothesis. It is suggested that B27 heavy chains can form stable dimers that accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum, initiating the ERUPR. In addition, heavy chains and dimers can bind to other immune receptors such as the natural killer receptors (NKRs), leading to expression and survival of more inflammatory leukocytes. However, contradictory evidence indicates that this pathogenesis may not be responsible. [8]

Other theories suggest that the T-cell antigen is the true susceptibility factor, or imply an innate etiology unrelated to HLA. Finally, HLA-B27 may simply represent a marker locus, closely linked to the as yet unidentified true immune response gene responsible for the inflammatory response. [9]

Several hypotheses with animal models have been proposed to explain the association of AAU and HLA-B27. Many cases of uveitis or RA follow gram-negative bacillary (eg, Ureaplasma, Shigella, Salmonella, Klebsiella, and Yersinia) dysentery or chlamydial infection, potentially explained by the immunogenic lipopolysaccharide in their cell walls. Also, chronic infection of a joint or the eye with intracellular chlamydiae might stimulate, via HLA-B27, a CD8 T-cell effector mechanism that indirectly injures the eye as a bystander. [11]

Animal experiments with rodents expressing human HLA-B27 indicate bacterial infection of the gut predisposes to arthritis and a RA-like syndrome. Decreased gut diversity is present in healthy and symptomatic HLA-B27 carriers, with the extent of dysbiosis directly correlating with symptom severity. [33] Additionally, specific CD8 T-cell lines present in the blood and joints of HLA-B27 carriers express gut homing factors, suggesting migration between these spaces. [32] In light of these findings, and the tendency of AAU and RA to arise in response to gram-negative coliforms, the gut microbiome’s association with HLA-B27 is a topic of interest.

Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Acute Anterior Uveitis

HLA-B27 associated AAU is the most frequent type of non-infectious uveitis (see Figure 1), accounting for 18-32% of cases in western countries and for 6-13% of cases in Asia. The relatively lower frequency in Asia is related to the lower frequency of HLA-B27 found in this population. As mentioned, there are varying global patterns of HLA-B27-associated AAU that may be attributed to genetic factors, such as HLA-B27 polymorphisms and non-MHC genes. [12, 13]

Studies indicate that HLA-B27-associated uveitis is a distinct entity characterized by a male predominance and frequent association with seronegative spondyloarthropathies, such as AS, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. [14] The first episode of HLA-B27 associated AAU most commonly occurs at 20-40 years of age, whereas the onset of HLA-B27-negative AAU tends to occur a decade later. Of patients with AAU, 50-60% may be HLA-B27 positive. AAU from HLA-B27 usually presents unilaterally with a classic triad of symptoms of acute pain, redness, and photophobia.

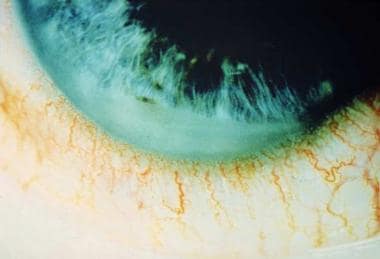

Corneal manifestations typically include fine keratic precipitates. More rarely, fibrin may collect in the anterior chamber and on the corneal endothelium. Corneal edema may result from endothelial compromise and decompensation. Band keratopathy, an accumulation of calcium in the corneal epithelium, may be seen in chronic uveitis. The anterior chamber shows cells and flare, reflecting protein accumulation in the anterior chamber due to the breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier. In severe inflammation, fibrinous exudate in the anterior chamber may occlude the pupil, causing iris bombe (see Figure 2). Findings must be differentiated from endophthalmitis. A hypopyon may be seen, and a spontaneous hyphema can rarely occur from the severely dilated iris vessels.

Figure 2. Anterior chamber fibrin collection in ankylosing spondylitis. Also appreciate the ciliary flush. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Figure 2. Anterior chamber fibrin collection in ankylosing spondylitis. Also appreciate the ciliary flush. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Pigment dispersion, pupillary miosis, and iris nodules may be noted. Synechiae, both anterior and posterior, can occur. The posterior segment rarely is involved, but cystoid macular edema, disc edema, pars plana exudates, or choroiditis may be seen. Intraocular pressure often is low, secondary to decreased aqueous production with inflammation of the ciliary body and trabecular meshwork. [15] Intraocular pressure also may be high if there is trabeculitis, pupillary block from a fibrin membrane, or clogging of trabecular meshwork by inflammatory debris.

Symptoms of AAU generally last a few days to weeks but can persist up to 3 months. Disease tends to recur in the same eye, especially in individuals who are HLA-B27 positive. Complications include cataract, glaucoma, hypotony, cystoid macular edema, papillitis, and synechiae formation. Some complications are more strongly associated with HLA-B27 positive AAU; however, no significant difference has been noted based on HLA-B27 status in measurement of final visual acuity or presence of posterior synechiae, cataract, and macular edema. [16, 17]

Classic AAU resolves completely when promptly and aggressively treated. Undertreated or misdiagnosed cases may progress to chronic iridocyclitis due to permanent damage of the blood-aqueous barrier.

Diagnosis

A careful history and physical examination helps distinguish between the uveitic entities associated with systemic disease and HLA-B27 from those that are not. Disease entities causing AAU are varied and include traumatic iritis, intraocular surgery, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, herpetic infection (both herpes simplex and herpes zoster), syphilis, sarcoidosis, Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, glaucomatocyclitic crisis, Behcet disease, and low-grade endophthalmitis. [18] COVID-19 also has been associated with AAU, but its relationship to HLA-B27 has not been elucidated. [34, 35, 36]

The role of HLA-B27 testing in patients with unilateral AAU is important in the differential diagnosis. The lack of HLA-B27 antigen in unilateral AAU may suggest other specific uveitis entities and systemic diseases. It also may be useful in determining the prognosis of AAU, as HLA-B27 associated AAU, even in the absence of systemic disease, is less favorable and more likely to recur when compared to HLA-B27 negative variants.

Treatment

Medical management of AAU involves topical corticosteroids and cycloplegics. Periocular corticosteroid injections are useful in chronic, recalcitrant, or noncompliant cases, particularly when the posterior segment is involved. Immunosuppressive therapy may be necessary in refractory cases or in those patients with corticosteroid-induced adverse effects. The primary endpoint of therapy is absence of cells in the anterior chamber, thereby minimizing complications including cataracts, cystoid macular edema, hypotony, synechiae formation, or glaucoma.

Cycloplegics help relieve photophobia, secondary to ciliary spasm, and prevent or break synechiae. In most cases, short-acting drops, such as 1% cyclopentolate hydrochloride or 1% tropicamide, are sufficient. These allow pupillary motility and rapid recovery when discontinued. Longer acting cycloplegics, such as 5% homatropine, 0.25% scopolamine, and 1% atropine also may be useful. If the uveitis is more severe, more frequent dosing of cycloplegics may be necessary.

Corticosteroids may be administered topically, intraocularly (intravitreal), systemically, or by periocular route. Topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of uveitis therapy. The goal is to use the minimum amount necessary to control inflammation and to prevent complications. Aggressive initial therapy may hasten recovery and limit the duration of therapy. Prednisolone acetate 1% given every hour is recommended for acute presentations. Ointment form is available to those who cannot tolerate the preservative in the drops and may be particularly useful for a longer-acting bedtime dosage. Usually, 2-3 weeks at maximal frequency is all that is necessary to eliminate inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber. A tapered regimen is recommended when discontinuing therapy.

If inflammation does not respond to topical therapy, patients with uveitis may require periocular, intraocular, or systemic corticosteroids, especially if the posterior segment is involved. Periocular corticosteroids usually are given as depot injections in the sub-Tenon space. Intravitreal corticosteroids, administered by injection of a sustained release implant, have demonstrated utility in the treatment of chronic uveitis. These sustained devices are particularly promising in treating long-standing inflammation, as they can release medications for several years after implantation. This would allow reduction or elimination of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, thereby minimizing systemic effects related to treatment with these agents. Notable ocular side effects of steroids include accelerated cataract development and glaucoma; therefore, intraocular pressures should be monitored on a regular basis.

Systemic corticosteroids can be administered orally or intravenously, and are especially effective in treating underlying systemic disease (eg, AS, RA) that requires therapy as well as the ocular disease. It is important to discuss the adverse effects of corticosteroids with patients and to have these monitored by a primary care physician. Prednisone at 1 mg/kg/d is a common starting dose and is titrated based on comorbidities and response.

More potent immunosuppression may be required in patients with vision-threatening inflammation, lack of response to corticosteroid treatment, or intolerance to corticosteroids. Patients taking 10 mg/d or more of corticosteroids to control their symptoms may benefit from an antimetabolite as a safer long-term treatment. Drugs used in these situations include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, methotrexate, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. These agents are more commonly used in posterior uveitis or panuveitis, but they occasionally can be required in severe fibrinous anterior uveitis associated with RA or AS. [19]

Therapies for uveitis are nonspecific, and their numerous adverse effects have led to increased interest in tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists (anti-TNF-alpha). TNF-alpha has been shown to be a critical inflammatory instigator in the pathogenesis of various forms of uveitis, including AAU. Anti-TNF-alpha infliximab is a murine-human chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against human TNF-alpha. It has been shown to be a rapid, effective, and safe therapy of vision-threatening ocular inflammation in Behçet disease and refractory posterior uveitis. Adalimumab, another TNF-alpha antagonist, has demonstrated effectiveness in treating recalcitrant uveitis in younger patient populations. [37] Etanercept is a genetically engineered fusion protein, which binds and inactivates both TNF-alpha and TNF-beta, though it is not recommended for treatment of HLA-B27 associated AAU due to an observed increase in AAU flare frequency compared to infliximab and and other TNF-alpha antagonists. [38, 39] Its use does, however, allow for the reduction of both systemic corticosteroids and/or systemic methotrexate.

HLA-B27 oral tolerance therapy also is being investigated. Oral tolerance therapy involves administering an antigen orally to induce a specific peripheral immune tolerance. Its mechanism is unclear, but it is believed that tolerance therapy revolves around suppression or clonal anergy dependent on the antigen dose. Oral tolerance has demonstrated experimental success in dealing with multiple sclerosis, arthritis, diabetes, myasthenia gravis, and uveitis. Based on this, clinical studies have been initiated using such antigens as myelin in multiple sclerosis, collagen in rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitogenic peptides in intermediate and posterior uveitis, again with signs of success and few adverse effects from the treatment. An HLA-B27-derived peptide (B27PD) mimicking retinal autoantigen has been found to be effective in both animal models and patients with uveitis.

Other emerging therapeutic options include antibiotic therapy in view of the implicated role of gram-negative bacterial infections on triggering HLA-B27 associated AAU. Sulfasalazine has been investigated for its potential to reduce AAU attack recurrence. Ciprofloxacin prophylaxis also has been studied, but was found to be non-beneficial due to drug adverse effects and cost.

Future novel potential treatments will be based on a better understanding of the immune system and the modulation of cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, and T-cell subsets.

The role of the rheumatologist in the management of AAU is important in identifying and managing underlying systemic diseases that may be co-involved, especially with the use of systemic immunomodulatory therapies. About 1% of HLA-B27 positive individuals develop AAU, and 84% of HLA-B27 positive patients with AAU will have Reiter's syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, or psoriatic arthritis. [20] It also is notable that 20-30% of patients diagnosed with Reiter's or AS develop AAU, putting importance on the identification of ophthalmologic conditions in existing rheumatology patients. [21]

Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Ankylosing Spondylitis

Initial observations of HLA-B27 association with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) were made in whites, though subsequent studies established the presence of HLA-B27 in patients with AS from nearly every ethnic group. A genetic link to HLA-B27 is suspected as HLA-B27 associated AS has been found to have a familial predisposition. [22]

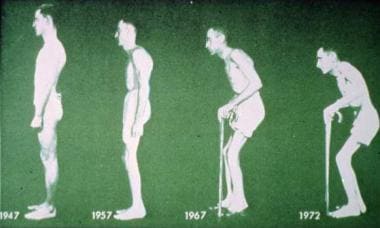

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, usually progressive, disease involving the articulations of the spine and adjacent soft tissues. The sacroiliac joints and proximal joints (hips and shoulders) are frequently affected whereas peripheral joint involvement is rare. The disease predominantly affects young men and begins most often in the third decade (see Figure 3). [23]

Figure 3. Ankylosing spondylitis causes progressive stiffening of the lumbar spine. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Figure 3. Ankylosing spondylitis causes progressive stiffening of the lumbar spine. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

HLA-B27 is found in 88% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. [24] The chance that an HLA-B27 patient will develop spondyloarthritis or eye disease is 1 in 4. [1]

Symptoms of AS include lower back pain and stiffness after inactivity. The disorder can be asymptomatic or severe and crippling. Often, symptoms of back disease are lacking in patients with iritis who are HLA-B27 positive, and not all patients who are HLA-B27 positive develop arthritic spinal or sacroiliac disease. [25]

Diagnosis

Radiographs of sacroiliac joints show sclerosis and narrowing of the joint space. This progresses to ligamentous ossification and osteoporosis. Both sacroiliac joints usually are involved but can be asymmetric.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) may first present to an ophthalmologist in the form of AAU. A family history or symptoms of back problems and a positive HLA-B27 are highly suggestive of the diagnosis. Sacroiliac films should be obtained, and the patient should be referred to an internist or a rheumatologist to monitor and manage the risk of deformity and systemic complications such as pulmonary apical fibrosis, aortitis, and aortic insufficiency.

Treatment

First-line treatments for active cases of ankylosing spondylitis include NSAIDs; however, there is no evidence to suggest increased efficacy of one NSAID over another. TNF inhibitors are recommended in refractory cases. Physical therapy is also effective in both active and stable disease. There is currently little evidence to support the use of systemic glucocorticoids in the management of AS. [26]

Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Reactive Arthritis

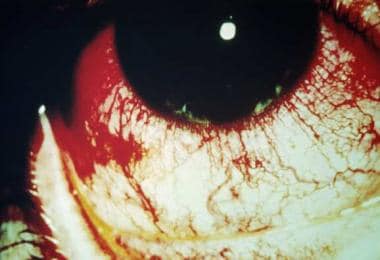

Reactive arthritis (RA) refers to spondyloarthropathies following enteric or urogenital infections and occurring in individuals who are HLA-B27 positive. Reactive arthritis originally was described as a triad of arthritis, nonspecific urethritis, and conjunctivitis (see Figure 4), often accompanied by iritis; however, it now is understood to include other major diagnostic criteria discussed below.

Figure 4. Reactive arthritis causing conjunctivitis (seen most prominently in everted palpebral conjunctiva) and ciliary flush. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Figure 4. Reactive arthritis causing conjunctivitis (seen most prominently in everted palpebral conjunctiva) and ciliary flush. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Like AS, RA occurs in individuals who are HLA-B27 positive; in fact, 60-85% of patients with reactive arthritis are HLA-B27 positive. The disease is most common in persons aged 18-40 years, but it has been known to occur in children and older adults. The sex ratio varies depending on whether the infection is acquired enterically (equal male:female) or venereally (predominantly male). Prevalence of the disease also is high in homosexual and bisexual men, owing to the high rate of genitourinary and gastrointestinal infections in this group. A particularly severe form of peripheral spondyloarthropathy following an infection has been described in patients with AIDS.

Etiology

The first bacterial infection noted to be causally related to reactive arthritis was Shigella flexneri. Other bacteria that have been implicated in reactive arthritis include several Salmonella species, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter jejuni, Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Clostridium difficile, and Ureaplasma urealyticum.

COVID-19 may be linked to reactive arthritis pending continued research to clarify the relationship and mechanism. [27, 28, 29]

Symptoms

RA usually begins with urethritis followed by conjunctivitis and rheumatological findings, as seen in Figure 5. Arthritis begins within 1 month of infection in 80% of patients. It usually is acute, asymmetric, and oligoarticular. It predominantly involves the joints of the lower extremities (eg, knees, ankles, feet, wrists). Dactylitis or “sausage digit” is a diffuse swelling of a solitary finger or toe. This is a distinct feature of both reactive arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendonitis also are common. Sacroiliitis is present in as many as 70% of patients. The eye is involved in 20% of patients, most commonly as a few days or weeks of papillary and mucopurulent conjunctivitis.

Figure 5. Reactive arthritis causing edema of the patient’s left knee (left) and bilateral conjunctivitis (right). Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Figure 5. Reactive arthritis causing edema of the patient’s left knee (left) and bilateral conjunctivitis (right). Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Punctate and subepithelial keratitis may occur rarely, leading to permanent corneal scars. Acute nongranulomatous iritis occurs in 10% of these patients and may become bilateral and chronic. Mucocutaneous lesions are common and appear in the mouth, palate, glans penis, palms, and soles.

In addition, two other mucocutaneous conditions are part of the major diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis, per the American Rheumatological Association (ARA) guidelines: (1) keratoderma blennorrhagicum: a scaly, erythematous, and irritating disorder of the palms and soles of the feet, and (2) circinate balanitis: a persistent, scaly, erythematous circumferential rash of the distal penis. The former may resemble pustular psoriasis, which can make it difficult to distinguish between these two seronegative arthropathies. Minor diagnostic criteria of reactive arthritis include sacroiliitis, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, nail bed pitting, palatal ulcers, and tongue ulcers.

Diagnosis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a clinical diagnosis without definitive laboratory or radiographic findings. The diagnosis should be considered when an acute asymmetric inflammatory arthritis or tendonitis follows an episode of diarrhea or dysuria. These diseases also are spondyloarthropathies involving the tendon insertion, not the synovium, primarily of weight bearing joints. HLA-B27 testing is not essential to confirm the diagnosis, but it may determine the eventual severity and chronicity of the condition. [30]

Treatment

Treatment is empiric and symptom-oriented. Patient education, reassurance, and physical therapy are paramount. Acute arthritis is treated with analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as indomethacin. Whether antibiotics help in reactive arthritis is unclear; however, it is known that treatment of acute chlamydial urethritis may prevent subsequent reactive arthritis.

Systemic corticosteroids should be avoided because they can aggravate the cutaneous manifestations of the disease, but local administration can help persistent monoarthritis, fasciitis, and tendonitis. In chronic destructive arthritis, cytotoxic drugs, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, may be beneficial. Uveitis usually is treated with topical steroids. Periocular steroids, systemic corticosteroids, and steroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapies can be used depending on the severity and response to treatment. [31]

Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease are associated with AAU. Specifically, 2.4% of patients with Crohn disease and 5-12% of patients with ulcerative colitis develop AAU. Sometimes, the iritis predates bowel disease, which may be asymptomatic. Early gut microbiome changes may herald development of inflammatory bowel disease in otherwise healthy HLA-B27 positive patients. [33] Approximately 50-75% of patients with spondylitis in association with inflammatory bowel disease have HLA-B27. In contrast, patients who develop sclerouveitis in the presence of inflammatory bowel disease tend to be HLA-B27 negative, and do not often develop sacroiliitis.

Diagnosis

Radiographs of involved peripheral joints are usually normal except for soft tissue swelling. Occasionally, patients with recurrent disease may show small bony erosions and joint space narrowing. Spine films show changes indistinguishable from ankylosing spondylitis. Blood work, including white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, usually reflect the intestinal disease.

Treatment

Treatment should be directed at the underlying inflammatory bowel disease. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can effectively treat the joint symptoms. Glucocorticoids, which are used for the control of colitis and extraintestinal manifestations, including uveitis, also may suppress arthritis. Physical therapy is beneficial for posture maintenance in spondylitis and for prevention of contractures in peripheral arthritis.

Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Psoriatic Arthritis

The prevalence of arthritis in patients with psoriasis is higher than that found in the general population. It occurs in about 5-42% of patients with psoriasis. HLA-B27 is associated with the pustular (stronger link) and peripheral (weaker link) forms of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PA), respectively. In the presence of spondylitis-associated psoriasis, 60-70% of these cases are HLA-B27 positive.

The age of onset of PA usually is in the third or fourth decade and occurs equally in both sexes. Psoriasis precedes the onset of arthritis by months or years. The prognosis of PA is more favorable than that of rheumatoid arthritis unless it is the severe destructive form called arthritis mutilans. The course of the disease is mild, intermittent, and it commonly affects the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints, with characteristic dactylitis. Knees, hips, ankles, temporomandibular joints, and wrists less frequently are involved. Most patients have onychodystrophy, which includes onycholysis and ridging and pitting of nail beds. One quarter of patients develop a more severe symmetrical arthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis, and 23% develop psoriatic spondylitis, which is less progressive and debilitating than that in AS.

Workup

Like most spondyloarthropathies, serum labs typically are normal except for nonspecific inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C reactive protein, and complement level. Axial presentations of HLA-B27 positive PA exhibit significant overlap with AS, and may be difficult to distinguish even with MRI. [40] Radiographic investigation shows findings similar to rheumatoid arthritis, but unique findings include erosions at the distal interphalangeal joints, expansion of the base of the terminal phalanx, pencil-in-cup appearance, and asymmetric or unilateral sacroiliitis.

Diagnosis

Psoriatic arthritis (PA) should be considered in individuals with arthritis and psoriasis. Psoriatic skin lesions can look like eczema and seborrheic dermatitis. Both RA and PA have dactylitis, but RA usually occurs in younger males, is less likely to be progressive and destructive, and is more likely to be associated with characteristic skin lesions, urethritis, and conjunctivitis.

Gout can look like PA, except for the presence of intra-articular sodium urate crystals. It is distinguished from rheumatoid arthritis by (1) the lack of rheumatoid factors; (2) the tendency for asymmetry, dactylitis, iritis, enthesopathy, and onychodystrophy; and (3) the high frequency of HLA-B27 in patients with spondylitis and sacroiliitis.

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is patient education with physical and occupational therapy. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce joint inflammation and pain. In more severe cases, hydrochloroquine can be beneficial in inducing disease remission but also exacerbate skin involvement. In extensive skin involvement, methotrexate can be used to relieve both skin lesions and arthritis. Renal function, liver function, and a complete blood cell (CBC) count should be performed regularly and titrated as necessary. Other effective drugs include sulfasalazine, intramuscular gold, cyclosporine, etretinate, and azathioprine.

-

Figure 4. Reactive arthritis causing conjunctivitis (seen most prominently in everted palpebral conjunctiva) and ciliary flush. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

-

Figure 2. Anterior chamber fibrin collection in ankylosing spondylitis. Also appreciate the ciliary flush. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

-

Figure 1. Acute anterior uveitis in AS. The perilimbal erythema or “ciliary flush” is typical of inflammation in the anterior segment. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

-

Figure 3. Ankylosing spondylitis causes progressive stiffening of the lumbar spine. Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

-

Figure 5. Reactive arthritis causing edema of the patient’s left knee (left) and bilateral conjunctivitis (right). Courtesy of Paul Dieppe, BSc, MD, FRCP, FFPHM.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Pathophysiology

- Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Acute Anterior Uveitis

- Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Reactive Arthritis

- Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Clinical Features of HLA-B27 Syndromes - Psoriatic Arthritis

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- References