Background

Lactose intolerance in adulthood is very common and is the result of a genetically programmed progressive loss of the activity of the small intestinal enzyme lactase. Some scientists believe that human adult lactase polymorphism evolved in the Neolithic period, after animal milk became available for the nutrition of older children and adults. Expression of the lactase enzyme starts to decline in most persons at age 2 years; almost 4 billion people worldwide have lactose malabsorption. However, symptoms of lactose intolerance rarely develop in people younger than 6 years.

Milk intolerance is more frequently due to milk-protein allergy than primary lactase deficiency. Although transient lactose intolerance may occur during acute gastroenteritis and as part of any process that leads to reduction of the small intestinal absorptive surface (such as untreated celiac disease), it is rarely clinically significant and, when present, can be easily treated with a short course of a lactose-free diet. Diagnosing lactose intolerance based on symptoms is fairly inaccurate; however, self-reported symptoms of lactose intolerance correlate with low calcium intake. Calcium supplementation should accompany any restriction of milk products.

Usually, very little morbidity is associated with lactase deficiency. Transient lactase deficiency affects a significant number of infants with severe gastroenteritis and diarrhea. Symptoms generally resolve within 5-7 days.

Pathophysiology

Lactose, a disaccharide unique to mammalian milk, is hydrolyzed into the monosaccharides glucose and galactose at the brush border of enterocytes on the villous tip by the enzyme lactase (a beta-D-galactosidase known as lactase phlorizin hydrolase).

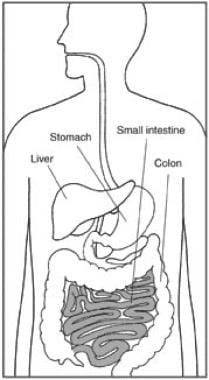

Lactose appears to enhance the absorption of several minerals, including calcium, magnesium, and zinc. The small intestine is a major site of absorption and is illustrated in the image below.

It also promotes the colonic growth of Bifidobacterium and is the source of galactose, which is an essential nutrient for the formation of cerebral galactolipids. The gene for lactase is located on chromosome 2. Hypolactasia seems to be strongly correlated with genotype C/C of the genetic variant C-->T(-13910) upstream of the lactase phlorizin hydrolase gene.

The molecular bases of lactose intolerance have been reviewed. [1]

Human and animal studies suggest that numerous modulators result in variable expression of lactase at different ages. Thyroxine may promote the decline in lactase enzyme expression that appears in childhood, whereas hydrocortisone appears to increase lactase levels. Although premature infants have partial lactase deficiency because of intestinal immaturity, enzyme expression can be induced by lactose ingestion. Improvement of lactose digestion in a previously intolerant child or adult is caused by growth of lactose-digesting bacteria rather than an induction in activity of the lactase enzyme because lactase is a noninducible enzyme.

A 2023 in vitro study that evaluated the impact of lactose on healthy adult gut microbiota by anaerobically culturing fecal samples with and without lactose from 18 donors found that samples with lactose added reduced richness and evenness but enhanced the prevalence of the beta-galactosidase gene. [2] The relative abundance of Bacteroidaceae fell in the lactose-treated samples, whereas levels of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillaceae, Enterococcaceae, Streptococcaceae) and the probiotic Bifidobacterium rose. These changes were associated with a rise in Veillonellaceae, which are lactate utilizers. Moreover, there was an increase in total short-chain fatty acids (acetate, lactate). [2]

Congenital lactase deficiency is an extremely rare autosomal recessive disorder associated with a complete absence of lactase expression. Childhood-onset and adult-onset lactase deficiency are extremely common and are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. The CC genotype of the 13910 C/T polymorphism of the LCT gene is linked to such late-onset primary hypolactasia. Persistent lactase activity into adulthood is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Acquired lactase deficiency, which is a transient phenomenon by definition, is due to damage of the intestinal mucosa by an infectious, allergic, or inflammatory process and resolves once the disease process is corrected and healing of the intestinal mucosa restores the brush border enzymes.

Etiology

Lactose intolerance

This is caused by a low or absent activity of the enzyme lactase.

Adult-onset lactose intolerance

This deficiency results from an unusual mechanism that involves a developmentally regulated change of the lactase gene product, resulting in a reduced synthesis of the precursor protein. Differences in the rate of gene transcription account for much of the differences in lactose intolerance observed among racial groups.

Low lactase activity in the small intestine

This allows undigested lactose to pass into the colon. In the colon, bacteria ferment the sugar to hydrogen gas and organic acids. The gas produces distention of the bowel, creating the sensation of bloating, cramping, and abdominal pain. Organic acids can be absorbed, but the quantity produced is rarely large enough to cause systemic symptoms or metabolic acidosis.

Epidemiology

United States data

Although as many as 20-25% of White US adults are believed to be lactase deficient, the true prevalence of this condition is unknown, as noted in a comprehensive National Institute of Health (NIH) consensus conference on the topic. [3] The prevalence in other racial groups parallels the country of racial origin. Symptomatic individuals represent only about 50% of lactase deficiency cases.

On average, both Black and Hispanic Americans consume less than the recommended levels of dairy foods, and perceived or actual lactose intolerance can be a primary reason for limiting or avoiding dairy intake, while true lactose intolerance prevalence is not known in these populations. A consensus statement provides an updated overview of the extent of this problem in such populations. [4]

International data

An estimated 68-70% of the global population has lactose intolerance. [5] Adult-onset lactase deficiency varies widely among countries. Northern Europeans have the lowest prevalence at approximately 5%. Central Europeans have a higher prevalence at approximately 30%, and Southern Europeans have a much higher prevalence at approximately 70%. Hispanic and Jewish populations also have a high prevalence at approximately 70%, whereas Northern Indians have a much lower prevalence than Southern Indians, at approximately 25% and 65%, respectively. Almost all (90%) Asians and Africans are affected.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the MEDLINE and Embase literature from inception to late 2016 comprising data from 450 study populations (N = 62,910) and 89 countries of individuals at least 10 years old found an estimated 68% global prevalence of lactose malabsorption (standardized for country size). [6] In Western, Southern, and Northern Europe, it was 28%, whereas in the Middle East it was 70%. Using genotyping data, the estimate of global prevalence was 74%; using lactose tolerance test data, it was 55%; and using hydrogen breath test date, it was 57%. [6]

Sex and age-related demographics

No sex differences in the prevalence of adult-type hypolactasia are known.

Lactase activity in the fetal intestine progressively increases through the third trimester and approaches maximum expression at term. Preterm infants have diminished levels of lactase. Few infants born at 28 weeks' gestation have significant intestinal lactase activity, whereas approximately 40% of infants born at 34 weeks' gestation demonstrate significant intestinal lactase activity. The premature neonatal period is the only time in which lactase enzyme production and expression can be induced. Because congenital lactase deficiency is exceedingly rare, diagnoses such as glucose-galactose malabsorption or the much more common milk-protein allergy should be considered in an infant with symptoms of milk or milk-based formula intolerance.

Lactase activity is genetically programmed to decline, beginning after age 2 years. Signs and symptoms usually do not become apparent until after age 6-7 years, and relatively recent studies have actually shown that hypolactasia may begin even after age 20. [7] Symptoms, therefore, may not be apparent until adulthood, depending on dietary lactose intake and rate of decline of intestinal lactase activity. Lactase enzyme activity is highly correlated with age, regardless of symptoms.

Secondary lactase deficiency due to intestinal mucosal injury can appear at any age; however, children younger than 2 years are very susceptible because of many factors, including a high sensitivity of the gut to infectious agents, low reserve because of the small intestinal surface area, and high reliance on milk-based products for nutrition.

Patient Education

Lower calcium levels are found in individuals with lactose intolerance; thus, emphasizing the importance of calcium supplementation is important. Again, despite lactose malabsorption, adults with lactose intolerance are able to tolerate substantial amounts of lactose-containing dairy products, such as milk (and even more yogurts). [3]

Although the symptoms are directly related to the quantity of lactose ingested, the patient should be educated about the fact that lactose may be hidden, in low amounts, in the following foods:

-

Breads

-

Baked goods

-

Cereals

-

Instant mixes

-

Margarine

-

Dressings

-

Candies

-

Snacks

-

Some over-the-counter drugs can reduce symptoms (eg, simethicone for relief of flatulence, exogenous lactase drops or tablets derived from yeast)

-

The small intestine is a major site of absorption.