Practice Essentials

Osteomyelitis is inflammation of the bone caused by an infecting organism. Although bone is normally resistant to bacterial colonization, it can become infected in multiple ways. The infecting organism may reach bone through blood or as a consequence of events such as trauma, surgery, the presence of foreign bodies, or the placement of prostheses that disrupt bony integrity and predispose to the onset of bone infection. When prosthetic joints are associated with infection, microorganisms typically grow in biofilm, which protects bacteria from antimicrobial treatment and the host immune response.

Early and specific treatment is important in osteomyelitis, and identification of the causative microorganisms is essential for antibiotic therapy. [1] The major cause of bone infections is Staphylococcus aureus;however, the causative organism depends on age and underlying conditions, among other factors. Management of osteomyelitis requires systemic treatment with antibiotics and local treatment at the site of bone infection to eradicate infection, and reconstruction is often required for the sequelae of bone and joint infection. The sequelae of osteomyelitis vary, depending on age at onset, site of infection, presence or absence of foreign bodies, and presence or absence of adjoining joint infection.

Anatomy

The bony skeleton is divided into two parts: the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton is the central core unit, consisting of the skull, vertebrae, ribs, and sternum; the appendicular skeleton comprises the bones of the extremities. The human skeleton consists of 213 bones, of which 126 are part of the appendicular skeleton, 74 are part of the axial skeleton, and six are part of the auditory ossicles.

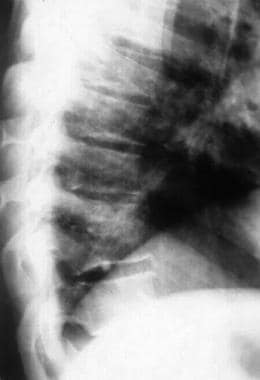

Hematogenous osteomyelitis most commonly involves the vertebrae, but infection may also occur in the metaphysis of the long bones, pelvis, and clavicle. Vertebral osteomyelitis usually involves two adjacent vertebrae with the corresponding intervertebral disk. (See the image below.) The lumbar spine is most commonly affected, followed by the thoracic and cervical regions. A form of hematogenous osteomyelitis that is more common occurs in infants and children and develops in the metaphysis.

Posttraumatic osteomyelitis begins outside the bony cortex and works its way in toward the medullary canal; it is typically found in the tibia but can occur in any bone. Contiguous-focus osteomyelitis often occurs in the bones of the feet in patients with diabetes mellitus and vascular compromise.

For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Skeletal System Anatomy in Adults and Osteology (Bone Anatomy).

Pathophysiology

Bone is normally resistant to infection. However, when microorganisms are introduced into bone hematogenously from surrounding structures or from direct inoculation related to surgery or trauma, osteomyelitis can occur. Bone infection may result from the treatment of trauma, which allows pathogens to enter bone and proliferate in the traumatized tissue. When bone infection persists for months, the resulting infection is referred to as chronic osteomyelitis and may be polymicrobial. Although all bones are subject to infection, the lower extremity is most commonly involved. [1, 2] Osteomyelitis can be acute, subacute, or chronic, depending on its duration.

Important factors in the pathogenesis of osteomyelitis include the following:

-

Virulence of the infecting organism

-

Underlying disease

-

Immune status of the host

-

Type, location, and vascularity of the bone

Bacteria may possess various factors that may contribute to the development of osteomyelitis. For example, factors promoted by S aureus may promote bacterial adherence, resistance to host defense mechanisms, and proteolytic activity. [3]

Hematogenous osteomyelitis

In adults, the vertebrae are the most common site of hematogenous osteomyelitis, but infection may also occur in the long bones, pelvis, and clavicle. [4]

Primary hematogenous osteomyelitis is more common in infants and children, usually occurring in the long-bone metaphysis. However, it may spread to the medullary canal or into the joint. When infection extends into soft tissue, sinus tracts eventually will form. Secondary hematogenous osteomyelitis is more common and can develop from any primary focus of infection or from reactivation of a previous infection in the presence of immunocompromised status. In adults, the location is also usually metaphyseal. [4]

The metaphysis is the region of a long bone between the epiphysis and the diaphysis. This part contains the growth plate and, because of its vascular characteristics, is the preferred region of hematogenous osteomyelitis. In particular, children younger than 5 years are susceptible to it due to the abundance of blood vessels with leaky endothelium that end in capillary loops.

In the long bones, the blood supply penetrates the bone at the midshaft but then splits into two segments traveling to each metaphyseal endplate. These vessels are terminal, and bacteria enter through the nutrient artery and lodge at the valveless capillary loops in the junction between the metaphysis and the physis. The blood flow through capillary loops and sinusoidal veins at the epiphyseal-metaphyseal junction is very slow, allowing the bacteria to establish and proliferate. This region does not permit good penetration of white blood cells and other immune mediators, thus serving to protect the bacteria.

As the bacteria continue to multiply, the scarce functioning phagocytes release enzymes that lyse the bone, thereby creating an inflammatory response. This results in formation of pus (a protein-rich exudate containing dead phagocytes, tissue debris, and microorganisms), increasing the intramedullary pressure in the area and thus further limiting the already compromised blood supply. The stasis and cytokine activity promote clot formation in the blood vessels, leading to bone ischemia and then necrosis.

Infection then spreads into the vortex through the Haversian system and Volkmann canals and finally into the subperiosteal space. The infection and the formation of pus in this region strip the periosteum from the shaft and stimulate an osteoblastic response. As a result, new bone is formed in response to the periosteal stripping. Part of the necrotic bone may separate; this is referred to as the sequestra.

In a severe infection, the entire shaft is encased in a sheath of new bone, which is referred to as the involucrum. Once this occurs, a major part of the shaft has been deprived of its blood supply.The involucrum can have openings called cloacae, which allow pus to escape from the bone, leading to fulminant disease. [5, 6, 7, 8]

In the 0- to 18-month age range, the epiphysis and the metaphysis have communicating vessels that result in direct extension of infection from metaphysis to epiphysis. Once the infection extends into the epiphysis, it leads to destruction of the epiphyseal cartilage and secondary ossification center, resulting in permanent growth impairment. The extension into the epiphysis also leads to a higher incidence of septic arthritis. [6]

S aureus is the pathogenic organism most commonly recovered from bone, followed by Pseudomonas and Enterobacteriaceae. Organisms less commonly involved include anaerobe gram-negative bacilli. Intravenous (IV) drug users may acquire pseudomonal infections. Gastrointestinal or genitourinary infections may lead to osteomyelitis involving gram-negative organisms. Dental extraction has been associated with viridans streptococcal infections. In adults, infections often recur and usually present with minimal constitutional symptoms and pain. Acutely, patients may present with fever, chills, swelling, and erythema over the affected area. [2, 9]

Contiguous-focus and posttraumatic osteomyelitis

The initiating factor in contiguous-focus osteomyelitis often consists of direct inoculation of bacteria via trauma, surgical reduction and internal fixation of fractures, prosthetic devices, spread from soft-tissue infection, spread from adjacent septic arthritis, or nosocomial contamination. Infection usually results approximately 1 month after inoculation.

Posttraumatic osteomyelitis more commonly affects adults and typically occurs in the tibia. The most commonly isolated organism is S aureus. At the same time, local soft-tissue vascularity may be compromised, leading to interference with healing. Compared with hematogenous infection, posttraumatic infection begins outside the bony cortex and works its way in toward the medullary canal. Low-grade fever, drainage, and pain may be present. Loss of bone stability, necrosis, and soft-tissue damage may lead to a greater risk of recurrence. [4, 9]

Septic arthritis may lead to osteomyelitis. Abnormalities at the joint margins or centrally, which may arise from overgrowth and hypertrophy of the synovial pannus and granulation tissue, may eventually extend into the underlying bone, leading to erosions and osteomyelitis. One study demonstrated that septic arthritis in elderly persons most commonly involves the knee and that, despite most of the patients having a history of surgery, 38% developed osteomyelitis.

Septic arthritis is more common in neonates than in older children and is often associated with metaphyseal osteomyelitis. Although rare, gonococcal osteomyelitis may arise in a bone adjacent to a chronically infected joint. [10, 11] In children the intra-articular position of some metaphyses makes them prone to the development of secondary septic arthritis (eg, in the knee, hip, or shoulder).

Many patients with vascular compromise, as in diabetes mellitus, are predisposed to osteomyelitis owing to an inadequate local tissue response. [4]

Infection in neuropathic or vascular-compromised feet is most often caused by minor trauma to the feet with multiple organisms isolated from bone, including Streptococcus species, Enterococcus species, coagulase-positive and -negative staphylococci, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic organisms. Fungal infections are also known in neuropathic feet with osteomyelitis. Foot ulcers allow bacteria to reach the bone. Patients may not experience any resulting pain, because of peripheral neuropathy, and may present with a perforating foot ulcer, cellulitis, or an ingrown toenail.

Treatment of osteomyelitis in diabetic feet is multidisciplinary and prolonged, involving complex debridements, soft-tissue cover, and antimicrobial and antifungal treatments.

Vertebral osteomyelitis

The incidence of vertebral osteomyelitis generally increases progressively with age, with most affected patients being older than 50 years. Although devastating complications may result from a delay in diagnosis, vertebral osteomyelitis has rarely been fatal since the development of antibiotics. However, the elderly have higher rates of bacteremia and infective endocarditis at the time of diagnosis, and they have a higher mortality than younger patients with osteomyelitis do. [12]

The infection usually originates hematogenously and generally involves two adjacent vertebrae with the corresponding intervertebral disk. The lumbar spine is most commonly affected, followed by the thoracic and cervical regions. [4, 1]

Potential sources of infection include skin, soft tissue, respiratory tract, genitourinary tract, infected intravenous (IV) sites, and dental infections. S aureus is the most commonly isolated organism. However, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is more common in IV drug users.

Most patients with vertebral osteomyelitis present with localized pain and tenderness of the involved vertebrae with a slow progression over 3 weeks to 3 months. Fever may be present in approximately 50% of patients. Some 15% of patients may have motor and sensory deficits. Laboratory studies may reveal peripheral leukocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Extension of the infection may lead to abscess formation. [4]

Osteomyelitis in children

Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis usually occurs after an episode of bacteremia in which the organisms inoculate the bone. The organisms most commonly isolated in these cases include S aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenza type b (less common since the use of vaccine for H influenza type b). The incidence of Kinsella kingae infection is increasing; such infection is a common cause of osteomyelitis in children younger than 4 years. [13]

Acute hematogenous S aureus osteomyelitis in children can lead to pathologic fractures. This can occur in about 5% of cases, with a 72-day mean time from disease onset to fracture. [14]

In children with subacute focal osteomyelitis (see the image below), S aureus is the most commonly isolated organism.

Rarefaction and periosteal new-bone formation around the left upper fibula in a 12-year-old patient. This was caused by subacute osteomyelitis.

Rarefaction and periosteal new-bone formation around the left upper fibula in a 12-year-old patient. This was caused by subacute osteomyelitis.

Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas species or Escherichia coli are common causes of infection after puncture wounds of the feet or open injuries to bone. Anaerobes can also cause bone infection after human or animal bites.

Osteomyelitis in the neonate results from hematogenous spread, especially in patients with indwelling central venous catheters. The common organisms in osteomyelitis of the neonate include those that frequently cause neonatal sepsis—namely, group B Streptococcus species—and E coli. Infections in the neonate can involve multiple osseous sites, and approximately half of the cases also involve eventual development of septic arthritis in the adjacent joint.

Children with sickle cell disease are at an increased risk for bacterial infections, and osteomyelitis is the second most common infection in these patients. The most common organisms involved in osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell anemia include Salmonella species, S aureus, Serratia species, and Proteus mirabilis.

Etiology

The major causes of osteomyelitis include the following:

-

Primary - Hematogenous

-

Secondary - Secondary to trauma, surgery, or sepsis of any etiology

Epidemiology

Approximately 20% of adult cases of osteomyelitis are hematogenous, which is more common in males for unknown reasons. [4]

The incidence of spinal osteomyelitis was estimated to be 1 in 450,000 in 2001. In subsequent years, however, the overall incidence of vertebral osteomyelitis is believed to have increased as a consequence of IV drug use, increasing age of the population, and higher rates of nosocomial infection due to intravascular devices and other instrumentation. [15, 16] The overall incidence of osteomyelitis is higher in developing countries.

Prognosis

Acute osteomyelitis is a surgical and medical emergency necessitating immediate antibiotic therapy, surgical drainage, and secondary procedures as needed. The prognosis of osteomyelitis depends on etiology, patient factors, and time to institution of suitable treatment, as well as a host of other factors (eg, location, organism, and antibiotic susceptibility and sensitivity).

Chronic osteomyelitis is prolonged in its course and can be extremely debilitating, with episodes of recurring infection interspersed with quiescent periods. The organisms become increasingly resistant, and local treatment carries more value than systemic therapy in the absence of acute exacerbation.

The complications of osteomyelitis, with all the comorbid factors and etiologic factors having been taken into account, can be extremely varied and may include sepsis and multiorgan dysfunction, stiffness, deformity, chronic discharging sinuses, limb-length discrepancies, chronic pain, loss of function, amputation, and even secondary cancers in sinus sites.

Patient Education

Patients who are diagnosed with bone and joint infection must be counseled specifically with reference to its short- and long-term consequences. Parents of children with osteomyelitis must be counseled regarding its possible effects on the growth plate and on adjacent joints and regarding the need for careful long-term follow-up until maturity. Patients with an implant must be counseled as to the possible nature of the infection, biofilms and their roles, the need for debridement or more radical measures (eg, implant removal), and the need for and effects of long-term antibiotic therapy.

-

Osteomyelitis of T10 secondary to streptococcal disease. Photography by David Effron MD, FACEP.

-

Rarefaction and periosteal new-bone formation around the left upper fibula in a 12-year-old patient. This was caused by subacute osteomyelitis.

-

Osteomyelitis, chronic. Image in a 56-year-old man with diabetes shows chronic osteomyelitis of the calcaneum. Note air in the soft tissues.

-

Osteomyelitis, chronic. Three-phase technetium-99m diphosphonate bone scans (static component) show increased activity in the heel and in the first and second toes and in the fifth tarsometatarsal joint.

-

Osteomyelitis, chronic. T1- and T2-weighted sagittal MRIs show bone marrow edema in L1 and obliteration of the disk space between L1 and L2.