Cygan J, Trunsky M, Corbridge T. Inhaled heroin-induced status asthmaticus: five cases and a review of the literature. Chest. 2000 Jan. 117 (1):272-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Self TH, Shah SP, March KL, Sands CW. Asthma associated with the use of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana: A review of the evidence. J Asthma. 2017 Sep. 54 (7):714-722. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rome LA, Lippmann ML, Dalsey WC, Taggart P, Pomerantz S. Prevalence of cocaine use and its impact on asthma exacerbation in an urban population. Chest. 2000 May. 117 (5):1324-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Han P, Cole RP. Evolving differences in the presentation of severe asthma requiring intensive care unit admission. Respiration. 2004 Sep-Oct. 71 (5):458-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Vaschetto R, Bellotti E, Turucz E, Gregoretti C, Corte FD, Navalesi P. Inhalational anesthetics in acute severe asthma. Curr Drug Targets. 2009 Sep. 10 (9):826-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rice JL, Matlack KM, Simmons MD, Steinfeld J, Laws MA, Dovey ME, et al. LEAP: A randomized-controlled trial of a lay-educator inpatient asthma education program. Patient Educ Couns. 2015 Jun 29. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asthma: most recent national asthma data. CDC. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. May 10, 2023; Accessed: November 15, 2024.

Hanania NA, David-Wang A, Kesten S, Chapman KR. Factors associated with emergency department dependence of patients with asthma. Chest. 1997 Feb. 111 (2):290-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asthma data visualizations. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/data-visualizations/default.htm#print.

Horton DB, Neikirk AL, Yang Y, Huang C, Panettieri RA Jr, Crystal S, et al. Childhood asthma diagnoses declined during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Respir Res. 2023 Mar 10. 24 (1):72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ye D, Gates A, Radhakrishnan L, Mirabelli MC, Flanders WD, Sircar K. Changes in asthma emergency department visits in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Asthma. 2023 Aug. 60 (8):1601-1607. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Asthma. CDC. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm. April 30, 2024; Accessed: May 19, 2024.

O'Hollaren MT, Yunginger JW, Offord KP, Somers MJ, O'Connell EJ, Ballard DJ, et al. Exposure to an aeroallergen as a possible precipitating factor in respiratory arrest in young patients with asthma. N Engl J Med. 1991 Feb 7. 324 (6):359-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

[Guideline] Dinakar C, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy J, et al. Management of acute loss of asthma control in the yellow zone: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014 Aug. 113 (2):143-59. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Oppenheimer J, Kerstjens HA, Boulet LP, Hanania NA, Kerwin E, Moore A, et al. Characterization of Moderate and Severe Asthma Exacerbations in the CAPTAIN Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024 Sep. 12 (9):2372-2380.e5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Magadle R, Berar-Yanay N, Weiner P. The risk of hospitalization and near-fatal and fatal asthma in relation to the perception of dyspnea. Chest. 2002 Feb. 121 (2):329-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Sarkar M, Bhardwaj R, Madabhavi I, Gowda S, Dogra K. Pulsus paradoxus. Clin Respir J. 2018 Aug. 12 (8):2321-2331. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Chakraborty RK, Chen RJ, Basnet S. Status Asthmaticus. 2024 Jan. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Summers RL, Rodriguez M, Woodward LA, Galli RL, Causey AL. Effect of nebulized albuterol on circulating leukocyte counts in normal subjects. Respir Med. 1999 Mar. 93 (3):180-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Samraj RS, Crotty EJ, Wheeler DS. Procalcitonin Levels in Critically Ill Children With Status Asthmaticus. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Oct. 35 (10):671-674. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Garg M, Saikia B, Chakrabarti A. Cut-off values of serum IgE (total and A. fumigatus -specific) and eosinophil count in differentiating allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis from asthma. Mycoses. 2014 Nov. 57 (11):659-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Hunt SN, Jusko WJ, Yurchak AM. Effect of smoking on theophylline disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976 May. 19 (5 Pt 1):546-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Jilani TN, Preuss CV, Sharma S. Theophylline. 2024 Jan. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Agarwal R, Sehgal IS, Muthu V, Denning DW, Chakrabarti A, Soundappan K, et al. Revised ISHAM-ABPA working group clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing, classifying and treating allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis/mycoses. Eur Respir J. 2024 Apr. 63 (4):[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Yuan YL, Zhang X, Liu L, Wang G, Chen-Yu Hsu A, Huang D, et al. Total IgE Variability Is Associated with Future Asthma Exacerbations: A 1-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 Jul. 9 (7):2812-2824. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

[Guideline] 2024 GINA Main Report. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Global Initiative For Asthma. Available at https://ginasthma.org/2024-report/. May 22, 2024; Accessed: October 25, 2024.

Carruthers DM, Harrison BD. Arterial blood gas analysis or oxygen saturation in the assessment of acute asthma?. Thorax. 1995 Feb. 50 (2):186-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Choi IS, Koh YI, Lim H. Peak expiratory flow rate underestimates severity of airflow obstruction in acute asthma. Korean J Intern Med. 2002 Sep. 17 (3):174-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Mamyrbekova S, Iskakova G, Faizullina K, Kuziyeva G, Abilkaiyr N, Daniyarova A, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of spirometry versus peak expiratory flow test for follow-up of adult asthma patients at primary care level. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2022 Sep 1. 43 (5):e58-e64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

[Guideline] Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/EPR-3_Asthma_Full_Report_2007.pdf. August 28, 2007; Accessed: October 4, 2024.

[Guideline] Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, Blake KV, Brooks EG, Bryant-Stephens T, DiMango E, et al. 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines: A Report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Dec. 146 (6):1217-1270. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Siegler D. Reversible electrocardiographic changes in severe acute asthma. Thorax. 1977 Jun. 32 (3):328-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Arshad H, Khan RR, Khaja M. Case Report of S1Q3T3 Electrocardiographic Abnormality in a Pregnant Asthmatic Patient During Acute Bronchospasm. Am J Case Rep. 2017 Feb 1. 18:110-113. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Saadeh CK, Goldman MD, Gaylor PB. Forced oscillation using impulse oscillometry (IOS) detects false negative spirometry in symptomatic patients with reactive airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003. 111:S136.

McFadden ER Jr. Acute severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Oct 1. 168 (7):740-59. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Trejo Bittar HE, Doberer D, Mehrad M, Strollo DC, Leader JK, Wenzel S, et al. Histologic Findings of Severe/Therapy-Resistant Asthma From Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017 Feb. 41 (2):182-188. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Schultz TE. Sevoflurane administration in status asthmaticus: a case report. AANA J. 2005 Feb. 73(1):35-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Fuller CG, Schoettler JJ, Gilsanz V, Nelson MD Jr, Church JA, Richards W. Sinusitis in status asthmaticus. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994 Dec. 33(12):712-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Sacha RF, Tremblay NF, Jacobs RL. Chronic cough, sinusitis, and hyperreactive airways in children: an often overlooked association. Ann Allergy. 1985 Mar. 54(3):195-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Schwartz HJ, Thompson JS, Sher TH, Ross RJ. Occult sinus abnormalities in the asthmatic patient. Arch Intern Med. 1987 Dec. 147(12):2194-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kacmarek RM, Ripple R, Cockrill BA, Bloch KJ, Zapol WM, Johnson DC. Inhaled nitric oxide. A bronchodilator in mild asthmatics with methacholine-induced bronchospasm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996 Jan. 153 (1):128-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Pfeffer KD, Ellison G, Robertson D, Day RW. The effect of inhaled nitric oxide in pediatric asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996 Feb. 153 (2):747-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ashutosh K. Nitric oxide and asthma: a review. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2000 Jan. 6 (1):21-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Dockhorn RJ, Baumgartner RA, Leff JA, Noonan M, Vandormael K, Stricker W, et al. Comparison of the effects of intravenous and oral montelukast on airway function: a double blind, placebo controlled, three period, crossover study in asthmatic patients. Thorax. 2000 Apr. 55 (4):260-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Camargo CA Jr, Smithline HA, Malice MP, Green SA, Reiss TF. A randomized controlled trial of intravenous montelukast in acute asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Feb 15. 167 (4):528-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ferreira MB, Santos AS, Pregal AL, Michelena T, Alonso E, de Sousa AV, et al. Leukotriene receptor antagonists (Montelukast) in the treatment of asthma crisis: preliminary results of a double-blind placebo controlled randomized study. Allerg Immunol (Paris). 2001 Oct. 33 (8):315-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Khedher A, Meddeb K, Sma N, Azouzi A, Fraj N, Boussarsar M. Pulmonary Barotrauma Including Huge Pulmonary Interstitial Emphysema in an Adult with Status Asthmaticus: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2018. 5 (5):000823. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Selroos O. Dry-powder inhalers in acute asthma. Ther Deliv. 2014 Jan. 5 (1):69-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Sep 13. 2013 (9):CD000052. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Andrews T, McGintee E, Mittal MK, et al. High-dose continuous nebulized levalbuterol for pediatric status asthmaticus: a randomized trial. J Pediatr. 2009 Aug. 155(2):205-10.e1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Best evidence topic reports. Bet 3. Endotracheal adrenaline in intubated patients with asthma. Emerg Med J. 2009 May. 26(5):359. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Stephanopoulos DE, Monge R, Schell KH, Wyckoff P, Peterson BM. Continuous intravenous terbutaline for pediatric status asthmaticus. Crit Care Med. 1998 Oct. 26(10):1744-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Newman LJ, Richards W, Church JA. Isoetharine-isoproterenol: a comparison of effects in childhood status asthmaticus. Ann Allergy. 1982 Apr. 48(4):230-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Chiang VW, Burns JP, Rifai N, Lipshultz SE, Adams MJ, Weiner DL. Cardiac toxicity of intravenous terbutaline for the treatment of severe asthma in children: a prospective assessment. J Pediatr. 2000 Jul. 137(1):73-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kalyanaraman M, Bhalala U, Leoncio M. Serial cardiac troponin concentrations as marker of cardiac toxicity in children with status asthmaticus treated with intravenous terbutaline. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011 Oct. 27(10):933-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kirkland SW, Vandenberghe C, Voaklander B, Nikel T, Campbell S, Rowe BH. Combined inhaled beta-agonist and anticholinergic agents for emergency management in adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 11. 1 (1):CD001284. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Craig SS, Dalziel SR, Powell CV, Graudins A, Babl FE, Lunny C. Interventions for escalation of therapy for acute exacerbations of asthma in children: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Aug 5. 8 (8):CD012977. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rodrigo GJ, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Anticholinergics in the treatment of children and adults with acute asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Thorax. 2005 Sep. 60 (9):740-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Castro-Rodriguez JA, Rodrigo GJ. Efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in infants and preschoolers with recurrent wheezing and asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar. 123(3):e519-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Doymaz S, Ahmed YE, Francois D, Pinto R, Gist R, Steinberg M, et al. Methylprednisolone, dexamethasone or hydrocortisone for acute severe pediatric asthma: does it matter?. J Asthma. 2022 Mar. 59 (3):590-596. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ream RS, Loftis LL, Albers GM, Becker BA, Lynch RE, Mink RB. Efficacy of IV theophylline in children with severe status asthmaticus. Chest. 2001 May. 119(5):1480-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Wheeler DS, Jacobs BR, Kenreigh CA, Bean JA, Hutson TK, Brilli RJ. Theophylline versus terbutaline in treating critically ill children with status asthmaticus: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005 Mar. 6(2):142-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Press S, Lipkind RS. A treatment protocol of the acute asthma patient in a pediatric emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1991 Oct. 30(10):573-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Griffiths B, Kew KM, Normansell R. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating children with acute asthma in the emergency department. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016 Sep. 20:45-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ciarallo L, Brousseau D, Reinert S. Higher-dose intravenous magnesium therapy for children with moderate to severe acute asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Oct. 154(10):979-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Glover ML, Machado C, Totapally BR. Magnesium sulfate administered via continuous intravenous infusion in pediatric patients with refractory wheezing. J Crit Care. 2002 Dec. 17(4):255-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Scarfone RJ, Loiselle JM, Joffe MD, Mull CC, Stiller S, Thompson K, et al. A randomized trial of magnesium in the emergency department treatment of children with asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2000 Dec. 36(6):572-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Bessmertny O, DiGregorio RV, Cohen H, et al. A randomized clinical trial of nebulized magnesium sulfate in addition to albuterol in the treatment of acute mild-to-moderate asthma exacerbations in adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 Jun. 39(6):585-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kumar J, Kumar P, Goyal JP, Rajvanshi N, Prabhakaran K, Meena J, et al. Role of nebulised magnesium sulfate in treating acute asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024 May 23. 8 (1):[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Vaiyani D, Irazuzta JE. Comparison of Two High-Dose Magnesium Infusion Regimens in the Treatment of Status Asthmaticus. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2016 May-Jun. 21 (3):233-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Graff DM, Stevenson MD, Berkenbosch JW. Safety of prolonged magnesium sulfate infusions during treatment for severe pediatric status asthmaticus. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019 Dec. 54 (12):1941-1947. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Beute J. Emergency treatment of status asthmaticus with enoximone. Br J Anaesth. 2014 Jun. 112 (6):1105-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Heshmati F, Zeinali MB, Noroozinia H, Abbacivash R, Mahoori A. Use of ketamine in severe status asthmaticus in intensive care unit. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003 Dec. 2(4):175-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Golding CL, Miller JL, Gessouroun MR, Johnson PN. Ketamine Continuous Infusions in Critically Ill Infants and Children. Ann Pharmacother. 2016 Mar. 50 (3):234-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Keenan LM, Hoffman TL. Refractory Status Asthmaticus: Treatment With Sevoflurane. Fed Pract. 2019 Oct. 36 (10):476-479. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Vohra R, Sachdev A, Gupta D, Gupta N, Gupta S. Refractory Status Asthmaticus: A Case for Unconventional Therapies. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018 Oct. 22 (10):749-752. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Elliot S, Berridge JC, Mallick A. Use of the AnaConDa anaesthetic delivery system in ICU. Anaesthesia. 2007 Jul. 62(7):752-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Burburan SM, Xisto DG, Rocco PR. Anaesthetic management in asthma. Minerva Anestesiol. 2007 Jun. 73(6):357-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kolli S, Opolka C, Westbrook A, Gillespie S, Mason C, Truitt B, et al. Outcomes of children with life-threatening status asthmaticus requiring isoflurane therapy and extracorporeal life support. J Asthma. 2023 Oct. 60 (10):1926-1934. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Wieruszewski ED, ElSaban M, Wieruszewski PM, Smischney NJ. Inhaled volatile anesthetics in the intensive care unit. World J Crit Care Med. 2024 Mar 9. 13 (1):90746. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Tobias JD. Inhalational anesthesia: basic pharmacology, end organ effects, and applications in the treatment of status asthmaticus. J Intensive Care Med. 2009 Nov-Dec. 24(6):361-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rishani R, El-Khatib M, Mroueh S. Treatment of severe status asthmaticus with nitric oxide. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999 Dec. 28(6):451-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Mroueh S. Inhaled nitric oxide for acute asthma. J Pediatr. 2006 Jul. 149(1):145; author reply 145. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Hunt LW, Frigas E, Butterfield JH, Kita H, Blomgren J, Dunnette SL, et al. Treatment of asthma with nebulized lidocaine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 May. 113 (5):853-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Schulz O, Wiesner O, Welte T, Bollmann BA, Suhling H, Hoeper MM, et al. Enoximone in status asthmaticus. ERJ Open Res. 2020 Jan. 6 (1):[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Di Lascio G, Prifti E, Messai E, Peris A, Harmelin G, Xhaxho R, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for life-threatening acute severe status asthmaticus. Perfusion. 2017 Mar. 32 (2):157-163. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Medar SS, Derespina KR, Jakobleff WA, Ushay MH, Peek GJ. A winter to remember! Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for life-threatening asthma in children: A case series and review of literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Feb. 55 (2):E1-E4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Coleman NE, Dalton HJ. Extracorporeal life support for status asthmaticus: the breath of life that's often forgotten. Crit Care. 2009. 13(2):136. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Hebbar KB, Petrillo-Albarano T, Coto-Puckett W, Heard M, Rycus PT, Fortenberry JD. Experience with use of extracorporeal life support for severe refractory status asthmaticus in children. Crit Care. 2009. 13(2):R29. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Noizet-Yverneau O, Leclerc F, Bednarek N, et al. [Noninvasive mechanical ventilation in paediatric intensive care units: which indications in 2010?]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010 Mar. 29(3):227-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Mikkelsen ME, Pugh ME, Hansen-Flaschen JH, Woo YJ, Sager JS. Emergency extracorporeal life support for asphyxic status asthmaticus. Respir Care. 2007 Nov. 52(11):1525-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ram FS, Wellington S, Rowe BH, Wedzicha JA. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for treatment of respiratory failure due to severe acute exacerbations of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25. CD004360. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ueda T, Tabuena R, Matsumoto H, Takemura M, Niimi A, Chin K, et al. Successful weaning using noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in a patient with status asthmaticus. Intern Med. 2004 Nov. 43(11):1060-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Leatherman JW, McArthur C, Shapiro RS. Effect of prolongation of expiratory time on dynamic hyperinflation in mechanically ventilated patients with severe asthma. Crit Care Med. 2004 Jul. 32(7):1542-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Silva Pde S, Barreto SS. Noninvasive ventilation in status asthmaticus in children: levels of evidence. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2015 Oct-Dec. 27 (4):390-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Stather DR, Stewart TE. Clinical review: Mechanical ventilation in severe asthma. Crit Care. 2005. 9 (6):581-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rampa S, Allareddy V, Asad R, Nalliah RP, Allareddy V, Rotta AT. outcome of invasive mechanical ventilation in children and adolescents hospitalized due to status asthmaticus in the United States: A population based study. J Emerg Med. vovember 2014. 47:571-2.

González García L, Rey C, Medina A, Mayordomo-Colunga J. Severe subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum secondary to noninvasive ventilation support in status asthmaticus. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016 Apr. 20 (4):242-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Ricketti PA, Unkle DW, Lockey R, Cleri DJ, Ricketti AJ. Case study: Idiopathic hemothorax in a patient with status asthmaticus. J Asthma. 2016 Sep. 53 (7):770-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rodrigo GJ, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Heliox-driven β2-agonists nebulization for children and adults with acute asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014 Jan. 112 (1):29-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Shiue ST, Gluck EH. The use of helium-oxygen mixtures in the support of patients with status asthmaticus and respiratory acidosis. J Asthma. 1989. 26(3):177-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kim IK, Phrampus E, Venkataraman S, Pitetti R, et al. Helium/oxygen-driven albuterol nebulization in the treatment of children with moderate to severe asthma exacerbations: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005 Nov. 116(5):1127-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Kudukis TM, Manthous CA, Schmidt GA, Hall JB, Wylam ME. Inhaled helium-oxygen revisited: effect of inhaled helium-oxygen during the treatment of status asthmaticus in children. J Pediatr. 1997 Feb. 130(2):217-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Anderson M, Svartengren M, Bylin G, Philipson K, Camner P. Deposition in asthmatics of particles inhaled in air or in helium-oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993 Mar. 147(3):524-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Carvalho I, Querido S, Silvestre J, Póvoa P. Heliox in the treatment of status asthmaticus: case reports. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2016 Jan-Mar. 28 (1):87-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Khawaja A, Shahzad H, Kazmi M, Zubairi AB. Clinical course and outcome of acute severe asthma (status asthmaticus) in adults. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014 Nov. 64 (11):1292-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Phumeetham S, Bahk TJ, Abd-Allah S, Mathur M. Effect of high-dose continuous albuterol nebulization on clinical variables in children with status asthmaticus. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015 Feb. 16 (2):e41-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves maintenance treatment for severe asthma. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-maintenance-treatment-severe-asthma. December 20, 2021; Accessed: May 19, 2024.

Panettieri R Jr, Lugogo N, Corren J, Ambrose CS. Tezepelumab for Severe Asthma: One Drug Targeting Multiple Disease Pathways and Patient Types. J Asthma Allergy. 2024. 17:219-236. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Corren J, Menzies-Gow A, Chupp G, Israel E, Korn S, Cook B, et al. Efficacy of Tezepelumab in Severe, Uncontrolled Asthma: Pooled Analysis of the PATHWAY and NAVIGATOR Clinical Trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 Jul 1. 208 (1):13-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

Oguzulgen IK, Turktas H, Mullaoglu S, Ozkan S. What can predict the exacerbation severity in asthma?. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007 May-Jun. 28(3):344-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Miller AG, Breslin ME, Pineda LC, Fox JW. An Asthma Protocol Improved Adherence to Evidence-Based Guidelines for Pediatric Subjects With Status Asthmaticus in the Emergency Department. Respir Care. 2015 Dec. 60 (12):1759-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

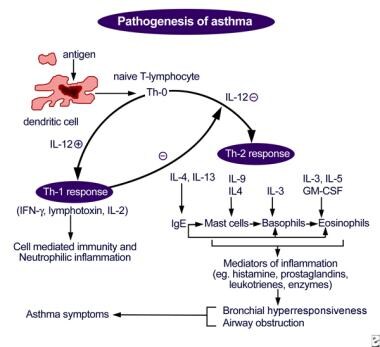

Antigen presentation by dendritic cell, with lymphocyte and cytokine response leading to airway inflammation and asthma symptoms.

Antigen presentation by dendritic cell, with lymphocyte and cytokine response leading to airway inflammation and asthma symptoms.