Background

Trichinosis, or trichinellosis, is caused by a parasitic nematode from the genus Trichinella. This disease, often unrecognized and underreported, has affected humans for thousands of years, with an estimated 10,000 cases occurring worldwide annually. [1, 2] Although virtually all mammals can be infected, humans are particularly susceptible to clinical disease through foodborne transmission. [3] Infection occurs when individuals consume inadequately cooked meat containing Trichinella larvae, primarily found in wild game and pork. Symptoms of trichinosis include diarrhea, myositis, fever, and periorbital edema, which arise when a significant number of larvae are ingested. [4]

The earliest documented human infection was found in an Egyptian mummy dating back to approximately 1300 BCE [5] ; this suggests an early cultural awareness of the link between human and animal infections, as reflected in religious prohibitions against pork consumption. [6]

The first modern scientific observations of human Trichinella infection were made by medical student James Paget, who reported findings from an autopsy of a man with a "sandy diaphragm." These observations were published by his lecturer, Sir Richard Owen, at the Royal College of Surgeons. [5] The life cycle of Trichinella was elucidated by Rudolf Virchow and his associates between 1850 and 1870. [6] Trichinella species are widely distributed across various geographic regions, including the Arctic, temperate lands, and tropics. [7]

Table 1. Biologic and Zoogeographic Features of Trichinella Species (Open Table in a new window)

Species |

Distribution |

Major Hosts |

Reported from Humans |

T spiralis |

Cosmopolitan |

Domestic pigs, wild mammals |

Yes |

T britovi |

Eurasia/Africa |

Wild mammals |

Yes |

T murrelli |

North America |

Wild mammals |

Yes |

T nativa |

Arctic/subarctic, Palaearctic |

Bears, foxes, walrus, seals, and wolves+ |

Yes |

T nelsoni |

Equatorial Africa |

Hyenas, felids |

Yes |

T pseudospiralis * |

Cosmopolitan |

Wild mammals, birds |

Yes |

T papuae * |

Papua New Guinea, Thailand, and Cambodia+ |

Pigs, crocodiles, and turtles+ |

Yes |

| T patagoniensis+ | South America+ | Cougars+ | No+ |

T zimbabwensis * |

East and South Africa |

Crocodiles, lizards, lions |

No |

* Nonencapsulating types |

|

|

|

Reprinted from Adv Parasitol, Vol 63, Murrell KD, Pozio E, Systematics and epidemiology of Trichinella, pg 367, 2006, with permission from Elsevier. [8]

Pathophysiology

Trichinella species require two hosts to sustain their life cycles, spreading through the ingestion of infected flesh rather than relying on traditional arthropod intermediate hosts. There are three major life cycles in nature: pig-to-pig, rat-to-rat, and transmission among carnivorous or omnivorous animals. Although rats and pigs are the most commonly associated with trichinosis, other animals such as walruses, seals, bears, polar bears, cats, raccoons, wolves, and foxes also may be infected, depending on the region.

The life cycle of Trichinella is maintained by animals that consume other animals containing encysted infective larvae in their striated muscles, such as pigs, horses, and predators such as bears, foxes, and boars. Humans can become infected by eating raw, undercooked, or inadequately processed meat from infected sources, primarily pigs, wild boar, or bear. After ingestion, the larvae excyst in the small intestine, penetrate the mucosal lining, and develop into adults within 6 to 8 days, with females measuring about 2.2 mm and males around 1.2 mm.

Mature females release live larvae for 4 to 6 weeks before dying or being expelled. The newborn larvae migrate through the bloodstream and lymphatic system, ultimately residing in striated skeletal muscle cells. They fully encyst within 1 to 2 months and can remain viable as intracellular parasites for several years. Dead larvae may be resorbed or calcify over time. The cycle continues only if another carnivore ingests the encysted larvae.

The life cycle of Trichinella species parasite is depicted in the image below.

Life cycle of Trichinella in humans. Courtesy of Dickson Despommier, PhD, and Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, Parasitic Diseases, 6th Ed, published by Parasites Without Borders (www.parasiteswithoutborders.com).

Life cycle of Trichinella in humans. Courtesy of Dickson Despommier, PhD, and Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, Parasitic Diseases, 6th Ed, published by Parasites Without Borders (www.parasiteswithoutborders.com).

The life cycle of Trichinella as a foodborne illness begins when raw or inadequately cooked meat containing viable larvae within cyst walls (nurse cells) is consumed. The acidic environment of the host's stomach releases the larvae from the cysts. The free larvae then migrate to the small intestine, where they attach to and penetrate the mucosal lining at the base of the villi. After undergoing four molts over 30 to 36 hours, they develop into adult worms, becoming obligate intracellular organisms. Adult males measure approximately 1.5 mm by 0.05 mm, whereas females measure about 3.5 mm by 0.06 mm. Around 5 days post-infection, females begin shedding live newborn larvae, measuring 80 µm by 7 µm (L1 stage). The female remains in the intestine for 4 weeks, releasing up to 1,500 larvae before being expelled in feces due to an adequate inflammatory response.

The newborn larvae enter the lymphatic and circulatory systems, migrating to well-vascularized striated skeletal muscle. The parasite preferentially targets metabolically active muscle groups, including the tongue, diaphragm, masseter, intercostal, laryngeal, extraocular, nuchal, pectoral, deltoid, gluteus, biceps, and gastrocnemius muscles. In tissues other than skeletal muscle, such as the myocardium and brain, the parasites disintegrate, causing intense inflammation and subsequent reabsorption.

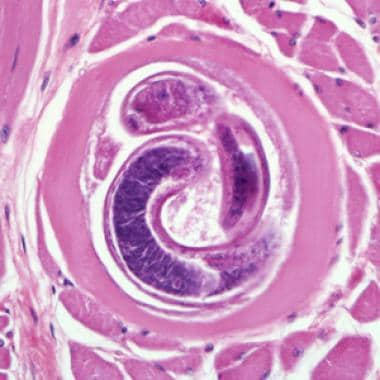

During the next 2 to 3 weeks, the larvae grow until they reach the fully developed L1 infective stage, increasing in size by up to tenfold. The adult worms are viviparous, and the larvae encyst, coiling and developing a surrounding cyst wall or nurse cell to survive harsher conditions, except for Trichinella pseudospiralis, which does not encyst. The complete life cycle takes 17 to 21 days, with larvae within the cyst wall averaging 400 µm by 260 µm, although lengths of 800 to 1,000 µm have been reported. The nurse cell–L1 complex can persist for 6 months to several years before calcification and death occur. The Trichinella life cycle is completed when a compatible host ingests the infected muscle (see images below).

Trichinella nurse cell. Courtesy of Dickson Despommier, PhD, and Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, Parasitic Diseases, 6th Ed, published by Parasites Without Borders (www.parasiteswithoutborders.com).

Trichinella nurse cell. Courtesy of Dickson Despommier, PhD, and Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, Parasitic Diseases, 6th Ed, published by Parasites Without Borders (www.parasiteswithoutborders.com).

Encysted larvae of Trichinella species in muscle tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The image was captured at 400X magnification. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

Encysted larvae of Trichinella species in muscle tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The image was captured at 400X magnification. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

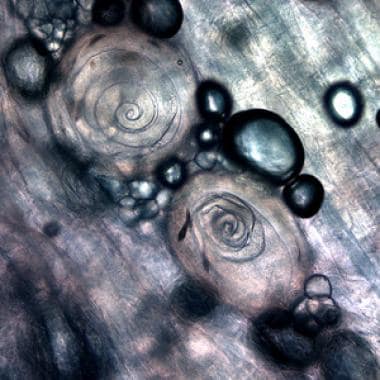

Trichinella larvae, in pressed bear meat, partially digested with pepsin. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ((https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

Trichinella larvae, in pressed bear meat, partially digested with pepsin. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ((https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

Larvae of Trichinella from bear meat. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

Larvae of Trichinella from bear meat. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

The intensity and frequency of exposure to infected meat determine the severity of the disease. The degree of infection is categorized as light (0-10 larvae ingested), moderate (50-500 larvae ingested), and severe (>1000 larvae ingested).

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

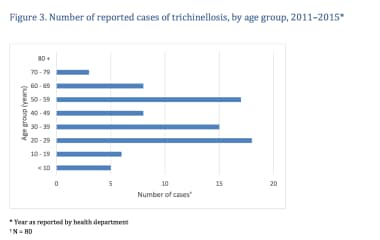

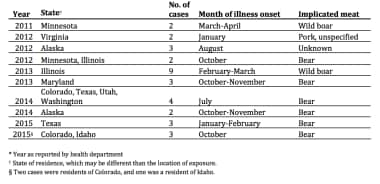

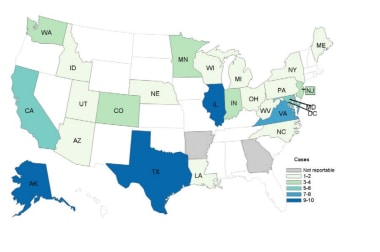

National surveillance data indicate a significant decline in reported trichinosis cases in the United States since 1947, the inaugural year of systematic data collection. Between 2011 and 2015, there were 80 reported cases across 24 states and the District of Columbia. Of these cases, 57 (71%) had a confirmed or suspected source, with 25 cases (44%) linked to bear meat, 13 cases (23%) to wild boar meat, and 9 cases (16%) linked to unspecified pork. [1] Notably, one case was associated with the consumption of residual larvae on a preparation table, [9] reinforcing the classification of trichinosis as a foodborne illness.

Hunters and individuals consuming carnivorous game remain at heightened risk, with the majority of cases since approximately the 1980s occurring among those who ingested lightly cooked wild game, particularly bear and wild boar. [10, 11, 12] The prevalence of infected domestic swine in the United States is approximately 0.001%; however, an autopsy study revealed a 4% incidence of historical infections. [11, 12, 13] A notable outbreak in 2008 in Northern California involved 38 individuals who consumed black bear infected with Trichinella murrelli, which also has been detected in raccoons and coyotes.

Epidemiology of trichinellosis in the US. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

Epidemiology of trichinellosis in the US. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

Reported cases of trichinellosis 2011-2015. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

Reported cases of trichinellosis 2011-2015. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

International

In Europe, where mandatory pork inspection is enforced, the majority of trichinosis cases are associated with horse or wild boar meat. In contrast, domestic pork is the primary source of infection in Latin America and Asia, with Trichinella infection rates in swine in China reported as high as 20%. Increased rates of trichinosis have been observed in former Eastern European countries, such as Romania and Hungary, attributed to political changes and evolving regional dietary practices. [14, 15] The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reported 779 human cases of trichinosis in the European Union in 2007, predominantly linked to farm and wild animal sources. [16]

Despite a substantial decline in the global incidence of trichinosis, outbreaks continue to occur frequently, particularly in developing nations. [17, 18] An estimated 10,000 cases are reported annually, with a mortality rate of approximately 0.2%. [1, 19] The international movement of processed food ingredients has introduced new challenges for control efforts. For instance, two clusters of cases in Germany in 1998 were traced to commercially produced sausage made from meat sourced from multiple European countries. A 2007 outbreak in Poland, involving over 180 confirmed cases, was linked to a single manufacturer of low-cost sausage, which subsequently spread to Germany through cross-border shoppers.

Travelers to regions with prevalent small-farm pig raising should exercise caution regarding pork products and avoid consuming any pork sausage. [13] An outbreak in Turkey was attributed to a producer who incorporated pork from unverified sources into beef meatballs. Whereas trichinosis primarily is associated with omnivorous or carnivorous animals, herbivores also can become infected, likely through feed contaminated with remnants of infected animals. In France, imported horse meat was implicated in over a dozen outbreaks, affecting more than 3,000 individuals between 1975 and 2005.

China reports some of the highest global case numbers, with serologic surveys indicating prevalence rates ranging from 0.66% to 12%, depending on regional dietary habits. The Yunnan province is particularly affected, with pigs serving as the primary vector and prevalence rates reaching 50% in certain slaughterhouse surveys. The Western Region Development strategy of the 1990s facilitated the migration of infected livestock to previously low-incidence areas, compounded by increased demand from the tourism sector.

Arctic and subarctic mammals, including polar bears, walruses, and seals, are recognized vectors for Trichinella nativa, which also can infect humans. This species exhibits resistance to freezing, with infection rates in polar bears in Nunavik reaching up to 60%. Some Inuit populations have modified their dietary practices to avoid older male walruses, which are primarily scavengers, whereas younger walruses feed predominantly on shellfish.

Consumption of wild boar sausage in Spain has resulted in human infections with T britovi, and wild boar have been identified as a source of infection in various Mediterranean regions, Southeast Asia, and Pacific Islands. This comprehensive overview underscores the clinical significance of trichinosis and highlights the importance of dietary and travel history in patients presenting with gastroenteritis, particularly when accompanied by eosinophilia or palpebral edema.

Mortality/Morbidity

Although Trichinella infections most likely are underreported in the United States, fewer than 25 cases are documented per year, with a very low mortality rate.

Specific death rate information is not established. Death is rare in the absence of neurologic or cardiac involvement.

Patients with light infection usually are asymptomatic. Those with mild symptoms improve in 2-3 weeks. Symptoms associated with heavy infections may persist for 2-3 months.

Factors that may affect morbidity include the quantity of larvae ingested, the species of Trichinella (most notably T spiralis), and the immune status of the host. Patients succumb to exhaustion, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, encephalitis, or cardiac failure and/or arrhythmia. Death from trichinosis usually occurs in 4-8 weeks but may occur as early as in 2-3 weeks.

Although most patients with muscle involvement have resolution of pain and associated disability, some may experience persistent myalgia and fatigue. In severe infections (very high larval load) muscle weakness may be enough to significantly impair mobility.

Following neurologic or cardiac involvement, persistent variable dysfunction of either system may develop, depending upon the distribution of lesions.

Race

Although Trichinella infections may be related to cultural differences in food cooking and storing methods (eg, the inadequate cooking or freezing of meat), outcomes do not vary based on race among infected individuals.

Culture

A 2017 outbreak involved the consumption of walrus meat in Alaska. [9] The first point of healthcare contact included village healthcare centers, which are primarily used by Alaskan Native populations. Traditional cultural practices, including the hunting of polar bear and walrus, may lead to differential infection rates with Trichinella within Alaska Native communities.

Some studies have found that cultural practices, such as avoidance of pork consumption in Jewish and Muslim communities, may serve as a protective factor against Trichinella infection. [20]

Sex

No differences in trichinosis rates between males and females are reported. Incidence is equal in males and females unless particular culinary habits lead to higher exposure for one group. [21]

Pregnant individuals have milder trichinosis symptoms than nonpregnant persons; however, abortions and stillbirths have been reported. There is evidence that pregnancy may offer some protection against infection. [22]

Symptoms of trichinosis typically are worse in lactating individuals compared with nonlactating persons.

Age

Children seem to be more resistant to Trichinella infection, although their symptoms can be more severe. They generally experience fewer complications and tend to recover more quickly. The figure below illustrates the cumulative number of trichinosis cases reported in the United States from 2011 to 2015, categorized by sex and age group. During this period, a total of 80 cases were reported among individuals with known ages, whereas age data was unavailable for one patient and sex data for another. Of the 80 cases, 51 were in males and 29 in females. Among the 53 patients with known ages, the median age was 37 years, with a range from 1 to 71 years.

All age groups have been affected by trichinellosis; however, it most commonly occurs in individuals aged 20 to 49 years, primarily due to dietary habits related to wild game consumption.

Serologic evidence suggests potential transplacental migration of larvae, although direct evidence of larvae presence only has been documented in various animals and in one case report involving a fetus from a therapeutic abortion of an infected individual. [22, 23, 24]

Prognosis

Severe disease occurs in only 5-20% of patients during epidemics.

Individuals who receive treatment with anthelmintics and, when necessary, corticosteroids typically make a full recovery, unless they have ingested a very high load of larvae, which increases the risk for cardiac and neurologic complications.

The likelihood of complete recovery is less certain if there is cardiac or neurologic involvement.

Patient Education

Adequate cooking and freezing methods prevent trichinosis.

The most effective measure to eradicate Trichinella species is by adequate cooking to kill the parasite. The current recommendation for heating is 160°F (71°C) for all food-borne disease. Trichinella species typically can be killed by adequate cooking to 140°F (60°C) for 2 minutes or 131°F (55°C) for 6 minutes. If no trace of pink in fluid or flesh is found, these temperatures have been reached.

Freezing also is an effective method for killing most species of Trichinella. For a 6-inch piece of meat, the recommended temperatures to kill larvae are as follows:

-

5°F (-15°C) for 20 days

-

-10°F (-23°C) for 10 days

-

-20°F (-29°C) for 6 days

Salting, smoking, or drying the meat does not kill cysts.

-

Encysted larvae of Trichinella species in muscle tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The image was captured at 400X magnification. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

-

Trichinella larvae, in pressed bear meat, partially digested with pepsin. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ((https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

-

Larvae of Trichinella from bear meat. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

-

The number of cases of trichinellosis by age. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

-

Epidemiology of trichinellosis in the US. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

-

Reported cases of trichinellosis 2011-2015. Courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/trichinellosis/resources/trichinellosis_surveillance_summary_2015.pdf).

-

Trichinella nurse cell. Courtesy of Dickson Despommier, PhD, and Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, Parasitic Diseases, 6th Ed, published by Parasites Without Borders (www.parasiteswithoutborders.com).

-

Life cycle of Trichinella in humans. Courtesy of Dickson Despommier, PhD, and Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, Parasitic Diseases, 6th Ed, published by Parasites Without Borders (www.parasiteswithoutborders.com).