Background

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) refers to a heterogeneous series of associated cardiac anomalies that involve the right ventricular outflow tract in which both of the great arteries arise entirely or predominantly from the right ventricle. The anatomic dysmorphology of double outlet right ventricle can vary from that of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) on one end of the spectrum to complete transposition of the great arteries (TGA) on the other end (see the image below).

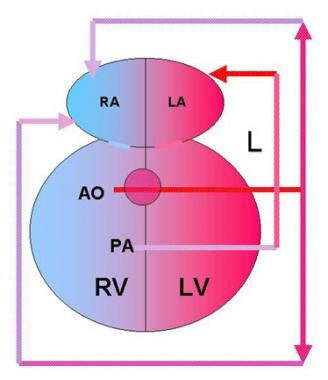

Double Outlet Right Ventricle Surgery. Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) with transposition of the great arteries accounts for 26% of cases of DORV. The aorta (AO) is anterior and to the right of the pulmonary artery (PA), and both arteries arise from the right ventricle (RV). The only outflow from the left ventricle (LV) is a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which diverts blood toward the RV. Pulmonary veins drain into the left atrium (LA) after blood has been oxygenated in the lungs (L). Systemic venous return is to the right atrium (RA).

Double Outlet Right Ventricle Surgery. Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) with transposition of the great arteries accounts for 26% of cases of DORV. The aorta (AO) is anterior and to the right of the pulmonary artery (PA), and both arteries arise from the right ventricle (RV). The only outflow from the left ventricle (LV) is a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which diverts blood toward the RV. Pulmonary veins drain into the left atrium (LA) after blood has been oxygenated in the lungs (L). Systemic venous return is to the right atrium (RA).

In the United States, the incidence of double outlet right ventricle is an estimated 0.09 cases per 1000 live births. Double outlet right ventricle comprises about 1-1.5% of all congenital heart disease. [1] No specific causal agent or predictive event has been identified.

The clinical presentation can vary from one of profound cyanosis to that of fulminant congestive heart failure. As a result, management and surgical repair of the defect are based on correcting the specific combination of anatomic defects with their radically different pathophysiologies.

Although hearts with atrioventricular discordance (ie, congenitally corrected TGA) or univentricular atrioventricular connections (ie, double inlet left ventricle) can be correctly grouped in this spectrum of anomalies, this article focuses on only those hearts with atrioventricular concordance and two functional ventricles.

History of the procedure

In 1793, Aberanthy described a heart with the origin of both great arteries from the right ventricle. [2, 3] The designation of “double outlet ventricle” was probably first reported by Braun et al in 1952. [4] The first successful biventricular repair for this entity was reported by Sakakibara et al in 1967. [5]

Problem

The definition of a double outlet right ventricle (DORV) has been a point of controversy among professionals in the field of congenital heart surgery. [6] However, the Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project defines double outlet right ventricle as a type of ventriculoarterial connection in which both great vessels arise either entirely or predominantly from the right ventricle. [7, 8]

In general, from a surgical perspective, defining the lesion as double outlet right ventricle is reasonable when more than 50% of both of the great arteries arise from the right ventricle. All of one vessel and most of the remaining vessel typically arise from the right ventricle. From the morphologic standpoint, some suggest that the absence of the fibrous continuity between the arterial and atrioventricular valves is a feature of double outlet right ventricle.

Relevant Anatomy

Before 1972, double outlet right ventricle (DORV) was defined as complete emergence of both great arteries from the right ventricle and no fibrous valvular continuity. The evaluation of this entity by Lev et al (1972) altered this classification; they proposed that aortomitral fibrous discontinuity was required. [9] In addition, Lev et al began to classify the group of anomalies in double outlet right ventricle by the ventriculoseptal defect (VSD) location (ie, the great vessel to which the VSD was anatomically adjacent).

Double outlet right ventricle is almost always associated with a VSD. Lev et al noted four possibilities of commitment of the double outlet right ventricle to the great arteries and termed them subaortic, subpulmonic, doubly committed, and noncommitted (or remote). [9] The location of the VSD has important implications on the physiologic manifestations of double outlet right ventricle and on surgical considerations.

The relative anatomic anomalies identified in the spectrum of double outlet right ventricle determine the clinical presentation and the surgical approach required for repair. Double outlet right ventricle can be described in terms of the relative position of the great arteries and the relative position of the VSD; the associated VSD is typically large and nonrestrictive.

Several associated cardiac anomalies are associated with double outlet right ventricle. Many of these affect the clinical presentation and the limits of the repair. Occurrence rates of associated cardiovascular anomalies are as follows [10] :

-

Pulmonary stenosis: 21-47% (most commonly observed with subaortic type VSD)

-

Atrial septal defect: 21-26%

-

Atrioventricular canal: 8%

-

Subaortic stenosis: 3-30%

-

Coarctation, hypoplastic arch, or interrupted aortic arch: 2-45%

-

Mitral valve anomalies: 30%

Pathophysiology

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) can be classified into four main categories on the basis of the location of the ventriculoseptal defect (VSD) in relation to great arteries:

-

Double outlet right ventricle with subaortic VSD

-

Double outlet right ventricle with subpulmonary VSD

-

Double outlet right ventricle with doubly committed VSD

-

Double outlet right ventricle with noncommitted VSD

Subaortic ventriculoseptal defect

Subaortic ventriculoseptal defect is the most common variant. The pathophysiology depends on the degree of pulmonary stenosis. With pulmonary stenosis, the pulmonary blood flow is decreased with variable degrees of cyanosis (Tetralogy of Fallot [TOF] type). In the absence of pulmonary stenosis, the pulmonary blood flow is increased, resulting in heart failure (VSD type).

Subpulmonary ventriculoseptal defect

In the subpulmonary ventriculoseptal defect variant of double outlet right ventricle, the pulmonary artery preferentially receives left ventricular (LV) oxygenated blood, and the desaturated blood from the right ventricle streams to the aorta (Transposition of the great arteries [TGA] type). The Taussig-Bing anomaly is a typical example of double outlet right ventricle with subpulmonary VSD. Aortic arch hypoplasia is a common association.

Doubly committed ventriculoseptal defect

The infundibular septum is absent in doubly committed ventriculoseptal defect, leaving both the aortic and pulmonary valves related to the VSD. Clinical features depend on the presence or absence of pulmonary stenosis.

Noncommitted ventriculoseptal defect

The noncommitted VSD is remote from the aortic and pulmonary valves. Most patients with noncommitted VSD undergo single ventricular palliative strategies.

Presentation

The clinical presentation and management of double outlet right ventricle (DORV) is primarily dependent on its type (ie, ventricular septal defect [VSD], Fallot, transposition of great arteries [TGA], noncommitted [remote] VSD), as well as the presence of associated cardiac anomalies. [10]

Recognition and identification of clinically significant cardiac anomalies might first be based on a complete history of the patient's condition and its progression from parents. Elucidate feeding tolerance, weight gain, breathing problems, and a general failure to thrive.

Complete physical examination should include an evaluation of the cardiac valvular sounds, any murmurs and thrills, the point of maximal impact, and heaving of the chest wall. In addition, abnormal pulmonary signs (eg, rales, rhonchi, wheezing) and peripheral signs of cyanosis and capillary refill should be sought.

The severity or lack of pulmonary stenosis largely determines the spectrum of symptoms and the patient's age at the time of clinical presentation. In general, most patients present during the neonatal period. Patients with severe pulmonary stenosis have cyanosis, and those with uncontrolled pulmonary blood flow present with congestive heart failure.

-

Double Outlet Right Ventricle Surgery. Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) with transposition of the great arteries accounts for 26% of cases of DORV. The aorta (AO) is anterior and to the right of the pulmonary artery (PA), and both arteries arise from the right ventricle (RV). The only outflow from the left ventricle (LV) is a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which diverts blood toward the RV. Pulmonary veins drain into the left atrium (LA) after blood has been oxygenated in the lungs (L). Systemic venous return is to the right atrium (RA).