Practice Essentials

Blastomycosis is a systemic pyogranulomatous infection, primarily caused by the inhalation of conidia (spores) of Blastomyces dermatitidis, although other species such as B gilchristii are also implicated in certain regions. [1, 2] This thermally dimorphic fungus, found in moist, acidic soils, exists in its mold form in the environment but transitions to a yeast form once inside the human host. Clinical presentations vary widely, ranging from an asymptomatic, self-limited pulmonary infection to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a life-threatening disease. [1]

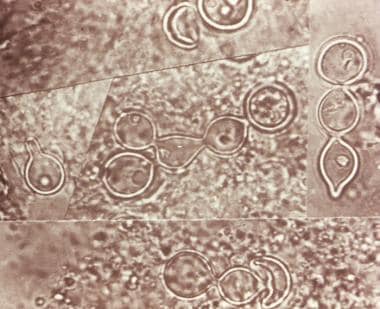

Composite photomicrograph of a tissue specimen from a patient with blastomycosis infection shows an abundance of large broad-based budding yeast that had been configured in chains. Courtesy of CDC/Dr. Lucille K. George.

Composite photomicrograph of a tissue specimen from a patient with blastomycosis infection shows an abundance of large broad-based budding yeast that had been configured in chains. Courtesy of CDC/Dr. Lucille K. George.

Clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations of blastomycosis vary significantly.

Asymptomatic or mild infection: A substantial percentage of individuals, possibly up to 50%, remain asymptomatic. [2]

Pulmonary infections: Blastomycosis usually is localized to the lungs and may present with:

-

Self-limited, flu-like illness, with fever, chills, myalgia, headache, and nonproductive cough

-

Acute illness resembling bacterial pneumonia, with fever, productive cough, and pleuritic chest pain. Patients may expectorate mucopurulent or purulent sputum

-

Chronic pulmonary infection that mimics tuberculosis or malignancy, presenting with low-grade fever, productive cough, fatigue, night sweats, and weight loss

-

Severe disease (eg, ARDS) that progresses to multilobar pneumonia, tachypnea, hypoxemia, and can lead to hemodynamic collapse. [3]

Extrapulmonary disease occurs in 25–40% of cases and often involves:

-

Cutaneous lesions, which are typically verrucous or ulcerative, often asymptomatic [3]

-

Osteoarticular infectionsthat cause bone pain and soft-tissue swelling,

Background

The treatment approach for blastomycosis depends on the severity of the disease, the clinical form, and the patient’s immune status. Two major antifungal agents—oral azoles (primarily itraconazole) and amphotericin B—are typically used, with the choice guided by the disease severity and the specific characteristics of the patient.

-

Pregnant individuals and CNS involvement : Amphotericin B is the recommended treatment for patients with CNS involvement or for pregnant persons. Itraconazole, though effective, is contraindicated in pregnancy due to potential teratogenic effects. CNS involvement requires amphotericin B because of its ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. [3, 4]

-

Moderately severe to severe disseminated disease : In more severe cases, particularly when blastomycosis has spread to other organs (eg, bones, skin, or CNS), the initial treatment should involve a lipid formulation of amphotericin B . This is followed by a long-term course of oral itraconazole once the patient shows clinical improvement. Amphotericin B is preferred for these patients because of its rapid fungicidal activity, which is critical in severe, life-threatening infections. [2, 4]

Duration of treatment

Blastomycosis requires prolonged treatment due to its systemic nature and the potential for relapses.

-

Bone involvement : In cases where the infection has spread to the bones, treatment should be extended to at least 12 months to prevent recurrence or chronic osteomyelitis. [3]

-

Severe disease : Patients with severe or CNS-involved blastomycosis may require even longer treatment durations, often depending on the response to the initial therapy and their overall health. [4]

This tailored approach to treatment and the prolonged duration are essential due to the risk of relapse and the slow clearance of the infection, especially in immunocompromised patients or those with chronic disseminated disease. [2, 3]

See Treatment and Medication.

Pathophysiology

Blastomycosis is a systemic pyogranulomatous infection caused by the inhalation of conidia (spores) of B dermatitidis, the asexual (imperfect) form of Ajellomyces dermatitidis, a dimorphic fungus. The identification of B helicus and B gilchristii has highlighted the genetic diversity within the Blastomyces genus. [2] These species, which are geographically distinct from B dermatitidis, contribute to understanding the global spread and variable pathogenicity of blastomycosis.

The mycelial form of B dermatitidis grows as a fluffy white mold at 25°C (77°F) and a brown folded yeast at 37°C (98.6°F). The conidia are round, ranging from 2 to 10 μm in diameter, and become aerosolized when the fungus in the mycelia phase in the soil is disturbed. These can be inhaled, passing into the lower respiratory tract and resulting in pulmonary infection.

The inhaled conidia are phagocytized by bronchopulmonary mononuclear cells. The organism’s susceptibility to phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils, monocytes, and alveolar macrophages explain why some individuals remain asymptomatic despite exposure to environments that would cause clinical infection in others. At 37°C (98.6°F), B dermatitidis converts from the mycelial form to the yeast form.

This transformation provides a survival advantage to the infecting fungus, as the yeast form is larger, at 8-10 μm in diameter, and possesses a thick cell wall that provides greater resistance to phagocytosis and killing. The histidine kinase DRK1 regulates dimorphism from mold to yeast and virulence gene expression in B dermatitidis. DRK1 knockout strain grown at 37°C (98.6°F) is locked in the mold morphology. [7] Another virulence factor is BAD-1, an immune-modulating glycoprotein that is expressed on the cell surface and released into the extracellular matrix. [8] BAD-1 facilitates the binding of B dermatitidis to macrophages. The yeast forms multiply and may disseminate through the blood and lymphatics to other organs. The evoked pyogranulomatous inflammatory response is a distinctive feature of blastomycosis characterized by an initial influx of neutrophils, followed by macrophage and granuloma formation.

Blastomycosis may be asymptomatic in nearly 50% of infected persons. In the remainder, the median incubation period from inhalation of the fungus to manifestations of symptoms is 45 days (range: 21-106 days). Symptoms of blastomycosis are similar to influenza, with most patients presenting with cough, fever, sputum production, chest pain, and dyspnea. Cellular immunity is a major protective factor in preventing progressive disease secondary to B dermatitidis.

The lungs are the usual point of entry. In one study, pulmonary involvement was present in 91% of all cases. [9] Pulmonary symptoms range from acute and chronic pneumonias to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Evidence of dissemination to other organs may be present.

Rarely, an extrapulmonary site (eg, skin, bone) may be the only presenting clinical manifestation.

In earlier reported case series, extrapulmonary involvement was noted in 50% of chronic blastomycosis cases. However, in present times, with earlier recognition and effective treatment, the extrapulmonary manifestations are seen in only about 20% of cases. Extrapulmonary dissemination occurs more commonly in patients with chronic pulmonary illness or immunocompromise.

Skin is the most common site of extrapulmonary blastomycosis and is involved in about 20% of cases. Other areas affected, and the approximate frequency of such involvement, are as follows [9] :

-

Bone: 5%

-

Prostate and other genitourinary organs: 2%

-

Meninges and brain:1%

-

Other (lymph nodes, adrenal, eye, liver, spleen, trachea, breast, and thyroid): 3%

Reactivation of blastomycosis may occur after a pulmonary infection that resolved, with or without treatment. An extrapulmonary site (eg, skin, bone, brain) is rarely a site of reactivation.

Etiology

Relatively recent advances in genotyping of Blastomyces by microsatellite typing and ITS2 sequencing have demonstrated that there are two unique clades, or species, of Blastomyces: B dermatitidis infection is more prevalent in patients with comorbidities and more likely to cause disseminated infection, and B gilchristii is more likely to cause isolated pulmonary disease. In a retropective review of children with blastomycosis confirmed by culture or cytopathology, the majority of the children had isolated pulmonary disease with systemic findings. [10] Those with extrapulmonary disease were less likely to have systemic symptoms or additional laboratory evidence of infection, which made delays in diagnosis more common. More than 90% of the pediatric cases were caused by B gilchristii. [1]

B dermatitidis is the asexual (imperfect) form of Ajellomyces dermatitidis, which is a thermal dimorphic fungus. The mycelial form grows as a fluffy white mold at 25°C (77°F) and a brown folded yeast at 37°C (98.6°F) body temperature. The fungus is usually isolated in the soil in its mycelial form in wet earth that has been enriched with animal droppings, rotting wood, and other decaying vegetable matter.

The conidia are round, ranging from 2 to 10 μm in diameter, and become aerosolized when the fungus in the mycelia phase is disturbed. The conidia are inhaled, passing into the lower respiratory tract and resulting in pulmonary infection. In infected tissue specimens, B dermatitidis appears as a characteristic thick-walled yeast, 8-10 μm in diameter, which provides greater resistance to phagocytosis and killing.

As dogs are infected with blastomycosis in a similar way and often in the same place as humans, an early clue to the diagnosis in humans is a history of a fungal infection in a pet dog. Blastomycosis is not transferred from animals to humans other than from bite wounds. [11] This condition has also been reported in other animals, including horses, cows, cats, bats, foxes, and lions.

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis, a systemic fungal infection caused by Blastomyces spp, can occur both endemically and sporadically. The disease primarily is reported in North America, specifically in the United States and Canada, although it has been documented in several other regions, including Central and South America, Africa, India, and parts of Europe. [12]

Geographic distribution in North America

The disease is most prevalent in areas around the Great Lakes, the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, and select regions in Canada (eg, Ontario, Manitoba). States with a high incidence include Arkansas, Wisconsin, Mississippi, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Illinois, and Louisiana. Of these, Wisconsin has some of the highest, with certain counties reporting as many as 10–40 cases per 100,000 people annually, and 2.9 hospitalizations per 100,000 person-years. [2]

Although blastomycosis is a reportable disease in only five US states—Arkansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin— evidence suggests that undetected cases in other regions may be more common than previously thought. For instance, a study from Vermont found a higher-than-expected incidence of 1.8 cases per 100,000 persons, comparable to or exceeding some traditionally high-incidence states. [4, 9, 13] These data highlight the need for more widespread surveillance.

Incidence and prevalence

The exact incidence of blastomycosis is likely underreported due to the limited number of states requiring mandatory surveillance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that US blastomycosis cases have been increasing, driven by environmental factors such as weather patterns and soil conditions. In Minnesota, for example, blastomycosis cases rose by 39% in 2022, largely attributed to favorable environmental conditions for fungal growth. [9, 10]

Risk factors

Blastomyces fungi thrive in moist, acidic soil, often near waterways, raising the susceptibility of individuals who live or work in these environments. High-risk activities include construction, excavation, hunting, camping, and fishing, which disturb the soil and can lead to the inhalation of spores. Past outbreaks have been linked to soil disruption during urban development, such as construction in Indianapolis from 2005 to 2008.

International spread

Although blastomycosis is primarily seen in North America, it has been increasingly reported in other parts of the world. Regions such as South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria have documented cases. Misdiagnosis as tuberculosis or other pulmonary conditions often delays the identification of blastomycosis in these areas. [9]

Demographics

Blastomycosis is more common in males, likely from increased exposure to environmental sources of infection through recreational or occupational activities. Studies suggest that 70% of US cases occur in males, and the disease tends to affect individuals aged 30 to 69 years. [9, 13]

United States statistics

Blastomycosis can be endemic or sporadic. Most cases of blastomycosis occur in the United States and Canada, although occasional cases have been reported in Central and South America, Africa, the United Kingdom, India, and the Middle East. [12] The disease is endemic in the central and southeastern parts of the United States, near the Mississippi River, Ohio River, and Great Lakes. Thus, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, Louisiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin are commonly affected. [14] However, blastomycosis is reportable only in five states: Arkansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. [15]

The true incidence and prevalence of blastomycosis are unknown, because there are no reliable antigen markers for skin testing. Its incidence in Northern Ontario has been reported as 117.2 cases per 100,000 population, the highest incidence in North America. [16] Based on confirmed cases, the annual US incidence is 1-2 cases per 100,000 people in Arkansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. [4] Wisconsin may have the highest incidence of blastomycosis of any state, with yearly rates ranging from 10 to 40 cases per 100,000 persons in some northern counties, [17] and 2.9 hospitalizations per 100,000 person-years. [18] 2012 data from Illinois and Wisconsin found an annual incidence of 0.4-2.6 cases per 100,000 population; in contrast, 2007-2017 data from New York revealed an average annual incidence of 0.1-0.2 cases per 100,000. [15]

There were 1,216 blastomycosis-related deaths in the United States during 1990–2010. [19] Among those 1,216 deaths, blastomycosis was reported as the underlying cause of death for 741 (60.9%) and as a contributing cause of death for 475 (39.1%). The overall age-adjusted mortality rate for the period was 0.21 per 1 million person-years. [19]

Significant construction, such as interstate road expansion, can release Blastomyces spores from the soil. [20] One such urban outbreak comprised 34 confirmed cases of blastomycosis in Indianapolis from 2005 to 2008, which coincided with a period of major highway construction in the same area. [20]

Residence near rivers and waterways is also associated with an increased risk of blastomycosis, particularly major freshwater drainage basins such as those of the Nelson River, St Lawrence River and northeast Atlantic Ocean Seaboard, Mississippi River System, and Gulf of Mexico Seaboard and southeast Atlantic Ocean Seaboard. [21] In Vilas County, north-central Wisconsin, 73 patients with laboratory-confirmed blastomycosis were identified over an 11-year period, in which 82% of these patients lived or had visited within 500 m of rivers or associated waterways. [22]

As noted under Etiology, canine blastomycosis can be an early warning sign for concomitant blastomycosis in humans. One case series of five households in which six patients were diagnosed with blastomycosis, one or more pet dogs were diagnosed with blastomycosis an average of 6 months before the patients themselves became symptomatic. [23]

Despite its increasing incidence, blastomycosis remains underreported in many regions due to nonmandatory surveillance in most states. The CDC has called for expanded surveillance and public awareness campaigns to improve detection and reporting, particularly in nonendemic areas. [9, 10]

International statistics

As noted earlier, blastomycosis can be seen outside of the United States. Internationally, most reported cases stem from Canada (Ontario, Manitoba) and Africa. Most African cases originate from South Africa [24] and Zimbabwe, [25] although cases have also been seen in Nigeria [26] and Tunisia. [27, 28] The disease is often mistaken for pulmonary tuberculosis or malignancy, and only after lack of response to standard treatment is the diagnosis made. [25, 26, 29] Cases have also been reported from disparate regions, including China, [16] Mexico, South America, the Middle East, and India. [12]

Because of the erroneous belief that the disease is limited to the United States, blastomycosis is often referred to as North American blastomycosis, which is an obsolete term. The term European blastomycosis is a confusing synonym of cryptococcosis, a systemic infection caused by the yeastlike fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Likewise, South American blastomycosis (ie, Brazilian blastomycosis) is an older name for paracoccidioidomycosis, a chronic, often fatal, mycosis caused by a large dimorphic fungus, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis.

Race, sexual, and age-related differences in incidence

Most studies of blastomycosis have shown no racial disparity in susceptibility. Rather, the distribution tends to mirror the ethnic and racial makeup of the area affected. However, in a few case series, certain races show a higher incidence of the disease. Some examples include an outbreak in Wisconsin, where 20 of the 55 patients affected were Hmong, [30] and an analysis of Missouri cases in which 57% of those affected were Black, although Black individuals account for only 13% of the population. [31] One possible explanation for these findings is that these groups have greater exposure to environments containing wet soil or organic matter where B dermatitidis thrives.

Blastomycosis has been reported to occur more frequently in males, possibly due to greater occupational and recreational exposure. Men are more likely to participate in activities associated with B dermatitidis, such as fishing, hunting, and camping. In Wisconsin from 1986 to 1995, 60% of cases were in males. [32] However, analysis of outbreak cases from a common source and more recent reports do not indicate a significant sex difference. [33] Moreoever, historically, epidemiologic reports were skewed due to the collection of data from Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals nationwide, which predominantly serve male patients. [34]

The mean age at diagnosis is approximately 45 years, with most patients aged 30-69 years. However, persons of any age can acquire the disease, including infants and very elderly persons. [35]

The disease is rare in children and adolescents. A retrospective study at a children's hospital in Arkansas identified only 10 patients diagnosed with the disease between 1983 and 1995. [36] In past reviews, however, about 2-10% of patients reported were younger than 15 years. In children, both sexes are equally susceptible.

Prognosis

Immunocompetent patients with blastomycosis generally do not experience complications and can expect a full recovery. Relapse or recurrence of blastomycosis is rare, and it varies by the therapeutic agent, treatment length, and patient's immune capacity. Successful blastomycosis treatment is achieved in 80-95% of cases. [10] In contrast, immunocompromised patients with blastomycosis have a poor prognosis.

Cellular immunity is the fundamental host defense against B dermatitidis. Loss or compromise in T-lymphocyte function—for example, in human immunodeficiency virus infection / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDs) or with immune suppression after solid organ transplant, can predispose to severe disseminated disease or cavitary lung disease, and it often involves the central nervous system (CNS). [37, 38, 39]

Complications of blastomycosis

Blastomycosis can result in a range of complications, particularly if the diagnosis or treatment is delayed, or in immunocompromised individuals. Complications may occur in various systems of the body due to the potential for dissemination beyond the lungs. The most significant complications include those discussed below. Effective management of blastomycosis requires early diagnosis and prompt treatment to reduce the risk of such complications. Delays in treatment can significantly increase the likelihood of long-term disability or death.

Pulmonary complications

-

Severe pulmonary disease complicated by cavitary lesions and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) occurs in approximately 20% of compromised hosts. [40]

-

Chronic pulmonary blastomycosis: Untreated or inadequately treated pulmonary infection may progress to a chronic state, mimicking tuberculosis, with features such as persistent cough, weight loss, and cavitary lesions in the lungs. [2]

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): In severe cases, particularly among immunocompromised patients, blastomycosis can rapidly progress to ARDS, a life-threatening condition characterized by severe hypoxemia, requiring mechanical ventilation. ARDS occurs in about 5–10% of patients with acute blastomycosis. [3]

Extrapulmonary dissemination

-

Extrapulmonary disease is frequently to the skin, bones, genitourinary system, and CNS, occurring in 25-40% of patients with blastomycosis.

-

Cutaneous blastomycosis: Dissemination to the skin is the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, presenting as verrucous or friable ulcerative lesions that may become secondarily infected if not treated. Complications include abscesses and nodules, and extensive cutaneous lesions may undergo central healing with scarring and contracture. Cutaneous involvement occurs in approximately 40–50% of disseminated cases. [2]

-

Osteoarticular blastomycosis: The bones and joints can be affected, leading to osteomyelitis (about 25% of cases, usually concomitant with pulmonary blastomycosis) [14] and septic arthritis, which can cause chronic pain and functional impairment. The infection can spread into nearby joints, leading to septic arthritis, or contiguous spread from the vertebral bodies can cause psoas abscesses. Involvement of the spine or pelvis can be particularly debilitating. [2]

-

Genitourinary complications: Involvement of the prostate and epididymis is a notable complication, leading to symptoms such as urinary retention, pain, or hematuria. Genitourinary blastomycosis is more common in men, and complications like abscess formation may occur. [4]

CNS involvement

-

CNS blastomycosis is a rare but serious complication that can manifest as meningitis or the formation of intracranial abscesses in 5-10% of cases. It appears to be 3-5 times more common in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent hosts. CNS involvement has a high mortality and requires aggressive antifungal treatment with amphotericin. [4] Meningitis or mass lesions has/have been reported to occur in approximately 40% of adult patients with AIDS. Cases of central diabetes insipidus have also been reported from CNS blastomycosis.

Mortality

-

Untreated disseminated disease: When blastomycosis disseminates beyond the lungs and is left untreated, the infection can be fatal. The overall mortality rate in severe cases has been reported between 4% and 22%, with higher mortality in immunocompromised patients, those with CNS involvement, or those developing ARDS. [2, 4]

Patient Education

Immunocompromised individuals in blastomycosis-endemic areas

Immunocompromised patients, including those with conditions such as HIV/AIDS, cannot entirely avoid exposure to B dermatitidis if they live in or visit blastomycosis-endemic areas. However, these individuals should be educated on strategies to reduce their risk for infection. Key preventive measures include avoiding activities that disturb soil in high-risk environments, such as wooded areas along rivers, lakes, or other waterways, where fungal spores are more likely to be present. They also should limit participation in occupational or recreational activities that involve soil disruption, such as construction, excavation, or hunting. [9, 10]

In addition, immunocompromised patients should be advised to monitor for early symptoms of blastomycosis and to seek prompt medical attention if they develop signs of respiratory illness, such as persistent cough, fever, or chest pain.

-

Cutaneous blastomycosis.

-

Lateral chest radiograph reveals the ill-defined lingular opacity and an absence of pleural effusions.

-

Composite photomicrograph of a tissue specimen from a patient with blastomycosis infection shows an abundance of large broad-based budding yeast that had been configured in chains. Courtesy of CDC/Dr. Lucille K. George.