Practice Essentials

Orofacial clefts—including cleft lip (CL), cleft lip and palate (CLP), and cleft palate (CP) alone, as well as median, lateral (transversal), and oblique facial clefts—are among the most common congenital anomalies. [1] The incidence of orofacial cleft is approximately 1 in every 500-550 births. The prevalence varies by ethnicity, country, and socioeconomic status.

Children who have an orofacial cleft require several surgical procedures and multidisciplinary treatment and care; a conservative estimate of the lifetime medical cost for each child with an orofacial cleft is $100,000, [2] which amounts to $750 million for all children with orofacial cleft born each year in the United States. In addition, these children and their families often experience serious psychological problems. [3, 4]

With rapidly advancing knowledge in medical genetics and with new DNA diagnostic technologies, more cleft lip and palate anomalies are diagnosed antenatally, and more orofacial clefts are identified as syndromic. Although the basic rate of clefting (1:500 to 1:550) has not changed since Fogh-Andersen performed his pioneering 1942 genetic study distinguishing two basic categories of orofacial clefts—namely, CL with or without CP (CL/P) and CP alone [5] —these clefts can now be more accurately classified.

The correct diagnosis of a cleft anomaly is fundamental for treatment, for further genetic and etiopathologic studies, and for preventive measures correctly targeting the category of preventable orofacial clefts.

Most individuals with CL, CP, or CLP, as well as many individuals with other craniofacial anomalies, require the coordinated care of providers in many fields of medicine (including otolaryngology) and dentistry, along with that of providers in speech pathology, audiology, genetics, nursing, mental health, [6] and social medicine (see Treatment).

No single treatment concept has been identified, especially for CLP. The timing of the individual procedures varies in different centers and with different specialists.

Pathophysiology

Embryology

In facial morphogenesis, neural crest cells migrate into the facial region, where they form the skeletal and connective tissue and all dental tissues except the enamel. Vascular endothelium and muscle are of mesodermal origin. [7]

The upper lip is derived from medial nasal and maxillary processes. Failure of merging between the medial nasal and maxillary processes at 5 weeks' gestation, on one or both sides, results in CL. CL usually occurs at the junction between the central and lateral parts of the upper lip on either side. The cleft may affect only the upper lip, or it may extend more deeply into the maxilla and the primary palate. (Cleft of the primary palate includes CL and cleft of the alveolus.) If the fusion of palatal shelves is impaired also, the CL is accompanied by CP, forming the CLP anomaly.

CP is a partial or total lack of fusion of palatal shelves. It can occur in the following ways:

-

Defective growth of palatal shelves

-

Failure of the shelves to attain a horizontal position

-

Lack of contact between shelves

-

Rupture after fusion of shelves

The secondary palate develops from the right and left palatal processes. Fusion of palatal shelves begins at 8 weeks' gestation and continues usually until 12 weeks' gestation. One hypothesis is that a threshold is noted beyond which delayed movement of palatal shelves does not allow closure to take place, and this results in a CP.

Classification

Orofacial cleft anomalies are a heterogeneous group, comprising both typical orofacial clefts (eg, CL, CLP, and CP) and atypical clefts (eg, median, transversal, oblique, and other Tessier types of facial clefts). [8, 9] Typical and atypical clefts can both occur as an isolated anomaly, as part of a sequence of a primary defect, or as part of syndrome or a multiple congenital anomaly (MCA). Nonsyndromic orofacial clefts occur in approximately 65-70% of all cases. In the remainder, the cleft anomaly is part of a known monogenic syndrome, part of a chromosomal aberration, part of an association, or part of a complex of MCA of unknown etiology. (See Table 1 below.) Proportions may vary in different studies.

Table 1. Classification of Orofacial Clefts and Frequency of Different Diagnoses in 4433 Cases From 2,509,881 California Births [8] (Open Table in a new window)

| Type of Anomaly | No. | % of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| All anomalies | 4433 | 100.00 |

| Isolated anomalies | 2732 | 61.63 |

| CL | 718 | 16.20 |

| CLP | 1217 | 27.45 |

| CP | 784 | 17.69 |

| Atypical facial cleft | 13 | 0.29 |

| Sequences | 173 | 3.90 |

| Robin sequence | 134 | 3.02 |

| Holoprosencephaly sequence | 36 | 0.81 |

| Frontonasal dysplasia sequence | 2 | 0.05 |

| Amyoplasia congenita disruption sequence | 1 | 0.02 |

| Chromosomal aberrations | 390 | 8.79 |

| Trisomy 21 | 20 | 0.45 |

| Trisomy 13 | 143 | 3.23 |

| Trisomy 18 | 80 | 1.80 |

| Other trisomies | 25 | 0.56 |

| Other chromosomal aberrations | 122 | 2.75 |

| Monogenic syndromes | 267 | 6.02 |

| Autosomal dominant | 194 | 4.38 |

| Autosomal recessive | 56 | 1.26 |

| X-linked dominant | 4 | 0.09 |

| Mostly sporadic but also autosomal dominant or recessive | 13 | 0.29 |

| Known environmental causes | 9 | 0.20 |

| Known associations | 35 | 0.79 |

| MCA of unknown etiology | 822 | 18.55 |

| MCA of malformation origin | 581 | 13.11 |

| MCA of deformation origin | 5 | 0.11 |

| MCA of malformation and deformation origin | 155 | 3.50 |

| MCA of disruption origin | 32 | 0.72 |

| MCA of disruption and malformation origin | 46 | 1.04 |

| MCA of other combinations | 3 | 0.07 |

| Conjoined twins | 5 | 0.11 |

| CL = cleft lip; CLP = cleft lip and palate; CP = cleft palate; MCA = multiple congenital anomaly. | ||

The varying physical characteristics of CL, CP, and CLP, as well as further issues in classification, are discussed in greater detail in Presentation.

Etiology

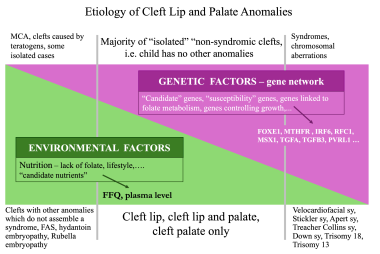

Most orofacial clefts, like most common congenital anomalies, are caused by an interaction between genetic and environmental factors (see the image below). In those instances, genetic factors create a susceptibility for clefts. When environmental factors (ie, triggers) interact with a genetically susceptible genotype, a cleft develops during an early stage of development.

Etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate: genetic and environmental factors. Image by Christine Rathbun.

Etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate: genetic and environmental factors. Image by Christine Rathbun.

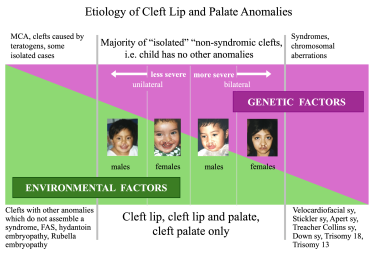

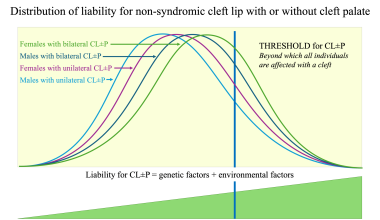

The relative proportions of environmental and genetic factors vary with the sex of the individual affected with cleft. In CL and CP, they also vary with the severity and the unilaterality or bilaterality of the cleft anomaly (see the image below). The highest proportion of genetic factors is in the subgroup of females with a bilateral cleft, and the smallest proportion is in the subgroup of males with a unilateral cleft.

Etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate: genetic and environmental factors in relation to sex and severity. Image by Christine Rathbun.

Etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate: genetic and environmental factors in relation to sex and severity. Image by Christine Rathbun.

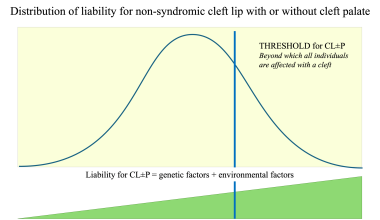

Thus, the classic multifactorial threshold (MFT) model of liability (see the first image below) can be applied to CL/P. On the basis of a large dataset of families with 2487 sibship of nonsyndromic CL/P, the author developed a four-threshold model in which the distribution of liability was expressed according to the sex of the proband and the severity of the cleft (see the second image below). [10] This model can facilitate understanding of differences in values of risk of recurrence as well as differences in prevention approaches between different subgroups of clefts. [11]

Multifactorial threshold model for distribution of liability for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Image by Christine Rathbun.

Multifactorial threshold model for distribution of liability for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Image by Christine Rathbun.

Four-threshold model for distribution of liability for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Image by Christine Rathbun.

Four-threshold model for distribution of liability for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Image by Christine Rathbun.

Theoretically, the subgroup of clefts closest to the population average should have the highest population prevalence, the lowest value of heritability, and thus the lowest risk of recurrence. This was confirmed in a large, population-based study of Whites with clefts. [11]

The value of heritability expresses a ratio of genetic and nongenetic factors. Heritability is equal to 1 for conditions completely controlled by genetic factors and equal to 0 for conditions completely controlled by environmental factors.

A higher proportion of environmental factors indicates a lower risk of recurrence and also provides a better chance to act preventively, given that the only modifiable etiologic factors are environmental factors. Thus, the subgroup whose average prevalence is closest to the population average consists of males affected with a unilateral CL/P. This subgroup is most common among orofacial clefts; the risk of recurrence for siblings and for offspring of an individual with cleft is the lowest, the value of heritability is the lowest, and the efficacy of primary prevention is the highest (see Treatment, Prevention).

A cleft develops when embryonic parts called processes (which are programmed to grow, move, and join with each other to form an individual part of the embryo) do not reach each other in time and an open space (cleft) between them persists. In the normal situation, the processes grow into an open space by means of cellular migration and multiplication, touch each other, and fuse together.

In general, any factor that could prevent the processes from reaching each other—for instance, by slowing down migration or multiplication of neural crest cells, by stopping tissue growth and development for a time, or by killing some cells that are already in that location—would cause a cleft to persist. Also, the epithelium that covers the mesenchyme may not undergo programmed cell death, so that fusion of processes cannot take place. [7]

DNA studies

There has been considerable interest in identifying genes that contribute to the etiology of orofacial clefting. Advances in modern molecular biology, developments in methods of genome manipulation, and availability of complete genome sequences led to an understanding of the roles of particular genes that are associated with embryonic development of the orofacial complex. [12]

The first candidate gene was transforming growth factor-α (TGFA), which showed an association with nonsyndromic CLP in a White population. [13] Lidral et al investigated five different genes (TGFA, BCL3, DLX2, MSX1, TGFB3) in a largely White population from Iowa. [14, 15] They found a significant linkage disequilibrium between CL/P and both MSX1 and TGFB3 and between CP and MSX1. The TGFB3 gene was identified as a strong candidate for clefting in humans on the basis of both the mouse model [16] and the linkage disequilibrium studies. [17, 15, 18]

Other candidate genes that were described as being associated with nonsyndromic CLP included D4S192, RARA, MTHFR, RFC1, GABRB3, PVRL1, and IRF6.

MSX1 was found to be a strong candidate gene involved in orofacial clefts and dental anomalies. Analysis of the MSX1 sequence in a multiplex Dutch family showed that a nonsense mutation (Ser104stop) in exon 1 segregated with the phenotype of nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. [19] Some have proposed that cleft palate in MSX1 knockout mice is due to insufficiency of the palatal mesenchyme. [20]

Zucchero et al reported that variants of IRF6 may be responsible for 12% of nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate, suggesting that this gene would play a substantial role in the causation of orofacial clefts. [21] A meta-analysis of all-genome scans of subjects with nonsyndromic CL/P, including Filipino, Chinese, Indian, and Colombian families, found a significant evidence of linkage to the region that contains IRF6. [22] A meta-analysis of 79 case-control studies found a significant association between the rs642961 and rs2235371 polymorphisms of IRF6 and the risk of nonsyndromic CL/P in the overall population. [23]

Gene-gene interactions have also been examined. A complex interplay of several genes, each making a small contribution to the overall risk, may lead to formation of clefts. Jugessur et al reported a strong effect of the TGFA variant among children homozygous for the MSX1 A4 allele (9 CA repeats). [24]

Much remains to be done in the evaluation of gene-environment interactions. Studies of the role of smoking in TGFA and MSX1 as covariates suggested that these loci might be susceptible to detrimental effects of maternal smoking. [18, 25] Folate-metabolizing enzymes such as methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), which is a key player in etiology of neural tube defects, and RFC1 are considered candidate genes on the basis of data suggesting that folic acid supplementation can reduce the incidence of nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. [26]

Of the more than 30 potential candidate loci and candidate genes throughout the human genome have been identified as strong susceptibility genes for orofacial clefts, MSX1 (4p16.1), TGFA (2p13), TGFB1 (19q13.1), TGFB2 (1q41), TGFB3 (14q24), RARA (17q12), and MTHFR (1p36.3) are among the strongest candidates. [22, 27, 28]

TGFB3 was identified as a strong candidate for clefting in humans based on a mouse model. Generally, palatogenesis in mice parallels that of humans and shows that comparable genes are involved. [29] Kaartinen demonstrated that mice lacking the TGFB3 peptide exhibit CP. [16] In addition, the exogenous TGFB3 peptide can induce palatal fusion in chicken embryos, though the CP is a normal feature in chickens. [30]

In humans, association studies between TGFB3 and nonsyndromic CL/P showed conflicting results. Lidral reported failure to observe an association of a new allelic variant of TGFB3 with nonsyndromic CL/P in a case-control study of the Philippines’ population. [14] Another study by Tanabe analyzed DNA samples from 43 Japanese patients and compared results with those from 73 control subjects with respect to four candidate genes, including TGFB3. [31] No significant differences in variants of TGFB3 between case and control populations were observed.

On the other hand, subsequent case-control association studies, family-based studies, and genome scans supported a role of TGFB3 in cleft development. Beaty examined markers in five candidate genes in 269 case-parent trios ascertained through a child with nonsyndromic orofacial clefts [18] ; 85% of the probands in the study were White. Markers at two of the five candidate genes (TGFB3 and MSX1) showed consistent evidence of linkage and disequilibrium due to linkage.

Similarly, Vieira attempted to detect transmission distortion of MSX1 and TGFB3 in 217 South American children from their respective mothers. [32] A joint analysis of MSX1 and TGFB3 suggested a possible interaction between these two genes, increasing cleft susceptibility. These results suggest that MSX1 and TGFB3 mutations make a contribution to clefts in South American populations.

In a study of the Korean population, Kim reported that the G allele at the SfaN1 polymorphism of TGFB3 is associated with an increased risk of nonsyndromic CL/P. The population study consisted of 28 patients with nonsyndromic CL/P and 41 healthy controls. [33]

In 2004, Marazita performed a meta-analysis of 13 genome scans of 388 extended multiplex families with nonsyndromic CL/P. [22] The families came from seven diverse populations including 2551 genotyped individuals. The meta-analysis revealed multiple genes in six chromosomal regions, including the region containing TGFB3 (14q24).

In the Japanese population, blood samples from 20 families with nonsyndromic CL/P were analyzed by using TGFB3 CA repeat polymorphic marker. On the basis of the results of the study, the investigators concluded that either TGFB3 itself or an adjacent DNA sequence may contribute to the development of cleft lip and palate. [34]

A study by Ichikawa et al investigated the relationship between nonsyndromic CL/P and seven candidate genes (TGFB3, DLX3, PAX9, CLPTM1, TBX10, PVRL1, TBX22) in a Japanese population. [35] The sample consisted of 112 patients with their parents and 192 controls. Both population based case-control analysis and family based transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) were used.

The results showed significant associations of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in TGFB3 and nonsyndromic CL/P, especially IVS+5321(rs2300607). [35] Although IVS-1572 (rs2268625) alone did not show a significant difference between cases and controls, the haplotype "A/A" for rs2300607- rs2268625 showed significant association. The author concluded that the results demonstrated positive association of TGFB3 with nonsyndromic CL/P in Japanese patients.

A study by Bu et al found evidence of an association between nonsyndromic CLP and SNPs in FOXF2 (6p25.3). [36]

Several micromanifestations of orofacial clefts have been studied, [37, 38] and additional candidate genes associated with these minimal, clinically less significant anomalies have been suggested. [37, 39]

Associations of specific candidate genes with nonsyndromic CL/P have not been found to be consistent across different populations. This may suggest that multiplicative effects of several candidate genes or gene-environmental interactions are noted in different populations.

The identification of factors that contribute to the etiology of nonsyndromic CL/P is important for prevention, treatment planning, and education. With an increasing number of couples who seek genetic counseling as a part of their family planning, the knowledge of how specific genes contribute to formation of nonsyndromic CL/P has gained an increased importance.

Noncoding RNAs and microRNAs

In a systematic review of 16 studies addressing the roles of noncoding RNAs in the development of craniofacial structures, Wei et al concluded that there is evidence that noncoding RNAs are involved in the formation of nonsyndromic CL/P. [40] Specifically, they play significant roles in the regulation of genes and signaling pathways related to nonsyndromic CL/P. [40]

There is now a growing understanding of the critical role of epigenetics in craniofacial development and the ways in which environmental factors interact with genetic susceptibility. Epigenetic regulators (eg, microRNAs [miRNAs]) play vital roles in the ontogeny of the orofacial region. As noted (see above), numerous genes have already been identified as being associated with orofacial clefts, and newer studies continue to be published. Epigenetic pathways thus may represent key vehicles in the regulation—and misregulation—of gene expression during normal and abnormal orofacial embryogenesis.

Over the past decade, significant strides have been made in identifying miRNAs and their target genes involved in lip and palate morphogenesis. Such morphogenetic processes include apoptosis, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Whereas some of the miRNA–target gene interactions have been functionally validated, many others exhibit causal relations that await functional confirmation. [41]

Epidemiology

Reported data on the frequency of orofacial clefts have varied according to the investigator and the country. In general, all typical orofacial cleft types combined occur in White populations with a frequency of 1 per 500-550 live births. Although the total combined frequency of CL, CLP, and CP is often used in statistics, combining the two etiologically different groups (ie, CL/P and CP alone) represents a misclassification bias similar to that of combining clefts with other congenital malformations.

The sex ratio in patients with clefts varies. In Whites, cleft lip and cleft lip and palate occur significantly more often in males, and cleft palate occurs significantly more often in females. In CL/P, the sex ratio correlates with the severity and laterality of the cleft. A large study of 8952 orofacial clefts in Whites found the male-to-female sex ratio to be 1.5-1.59:1 for CL, 1.98-2.07:1 for CLP, and 0.72-0.74:1 for CP. [11]

The prevalence of clefts varies considerably in different racial groups. The lowest rate is for Black individuals. A high prevalence of CL/P was found for the Japanese population, and the highest prevalence was found for the North American Indigenous populations.

In contrast, no remarkable variation among races was found in isolated CP. [8] In particular, its prevalence did not significantly vary between Black and White infants or between infants of Japanese and European origin in Hawaii. Leck considered that such findings may reflect a higher etiologic heterogeneity of CP than of CL/P. Methods of ascertainment and classification criteria undoubtedly influence prevalence figures.

In a large population-based study of 4433 children born with orofacial cleft (ascertained from 2,509,881 California births), the birth prevalence of nonsyndromic CL/P was 0.77 per 1000 births (CL, 0.29/1000; CP, 0.48/1000), and the prevalence of nonsyndromic CP was 0.31 per 1000 births (see Table 2 below). [42]

Table 2. Prevalence of Orofacial Clefts in 2,509,881 California Births (1983-1993) [8] (Open Table in a new window)

| Type of Cleft | No. | Prevalence per 1000 | Frequency Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 4433 | 1.77 | 1:566 |

| CL/P | 2634 | 1.05 | 1:953 |

| CP | 1651 | 0.66 | 1:1520 |

| Nonsyndromic, nonmultiple orofacial clefts | |||

| CL/P | 1935 | 0.77 | 1:1297 |

| CL | 718 | 0.29 | 1:3496 |

| CLP | 1217 | 0.48 | 1:2062 |

| CP | 784 | 0.31 | 1:3201 |

| CL = cleft lip; CLP = cleft lip and palate; CL/P = cleft lip with or without cleft palate; CP = cleft palate. | |||

In that study, the risk of CL/P was slightly lower among the offspring of non-US-born Chinese women compared to US-born Chinese women and slightly higher among non-US-born Filipinos relative to their US-born counterparts. For CP, lower prevalences were observed among Blacks and Hispanics than among Whites. The risk of CP was higher among non-US-born Filipinos compared to US-born Filipinos. These prevalence variations may reflect differences in both environmental and genetic factors affecting risk for development of orofacial cleft.

In a study that addressed the prevalence of birth defects in the United States for the period 2010-2014, Mai et al provided the following estimates for the total population: CL/P, 10.25/10,000; CLP, 6.67/10,000; CL, 3.51/10,000; and CP, 5.91/10,000. [43] In a subsequent study that addressed the prevalence of birth defects in the United States for the period 2016-2020, Stallings et al provided the following estimates for the total population: CL/P, 9.94/10,000; CLP, 6.54/10,00; CL, 3.41/10,000; and CP, 6.26/10,000. [44]

Indicators of lower socioeconomic status have been associated with an increased incidence of orofacial clefts; the specific indicators involved with CL/P appear to differ from those involved with CP alone. [45]

Risk of recurrence

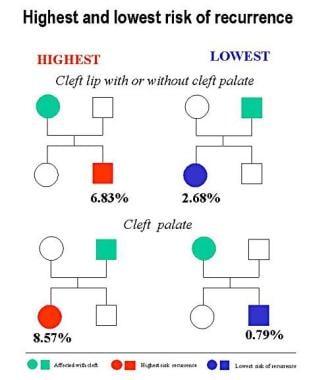

Genetic factors (ie, genes participating in the etiology of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts) are passed to the next generation, thus creating an increased risk for such anomaly in offspring. The risk of recurrence also differs with respect to proportion of genetic and nongenetic factors. In CL/P, the hypothetical four-threshold model (see Etiology) closely corresponds with differences in the risk of recurrence.

From a clinical point of view, the following two factors are most important in evaluating the risk of recurrence for CL/P:

-

Sex of the individuals (ie, patient and individual at risk)

-

Severity of the effect in the patient (eg, unilateral vs bilateral)

The lowest recurrence risk for CL/P is for the subcategory of male patients with unilateral cleft (see Table 3 below) and, within this category, for sisters of males with a unilateral cleft and for daughters of fathers with a unilateral CL/P (see the image below). The highest risk of recurrence of CL/P is for the subcategory of female patients affected with a bilateral CL/P.

Table 3. Recurrence Risk for Cleft Lip With or Without Cleft Palate (Open Table in a new window)

| Patient Sex (Type of Cleft) | Risk in Siblings, % | Risk in Children, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brother | Sister | Total | Son | Daughter | Total | |

| Male (unilateral) | 2.25 | 1.35 | 1.84 | 4.91 | 2.27 | 3.60 |

| Male (bilateral) | 4.17 | 4.41 | 4.29 | 11.54 | 4.88 | 8.60 |

| Female (unilateral) | 5.26 | 3.13 | 4.29 | 4.55 | 3.05 | 3.80 |

| Female (bilateral) | 15.78 | 7.14 | 12.12 | 17.24 | 7.69 | 12.73 |

| All | 3.91 | 2.67 | 3.34 | 6.41 | 3.11 | 4.82 |

The risk of recurrence for CP seems to be influenced only by sex. The risk is highest for daughters of fathers affected with a CP and lowest for sons of mothers affected with a CP (see Table 4 below).

Table 4. Recurrence Risk for Cleft Palate Only (Open Table in a new window)

| Patient Sex | Risk in Siblings, % | Risk in Children, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brother | Sister | Total | Son | Daughter | Total | |

| Male | 1.69 | 1.68 | 1.69 | 2.94 | 8.57 | 5.80 |

| Female | 2.70 | 2.25 | 2.48 | 0.79 | 2.86 | 1.73 |

| Total | 2.21 | 1.96 | 2.09 | 1.55 | 5.14 | 3.25 |

-

Examples of cleft lip.

-

Examples of cleft lip and palate.

-

Examples of cleft palate.

-

Submucous cleft palate.

-

Bilateral cleft lip on ultrasonogram.

-

Median cleft lip on ultrasonogram.

-

Highest and lowest risk of recurrence of cleft lip with or without cleft palate.

-

Recurrence of clefts in groups with and without vitamin and folic acid supplementation.

-

Recurrence of clefts in groups with and without vitamin and folic acid supplementation: unilateral vs bilateral.

-

Etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate: genetic and environmental factors. Image by Christine Rathbun.

-

Etiology of cleft lip and cleft palate: genetic and environmental factors in relation to sex and severity. Image by Christine Rathbun.

-

Multifactorial threshold model for distribution of liability for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Image by Christine Rathbun.

-

Four-threshold model for distribution of liability for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Image by Christine Rathbun.

-

Decreased occurrence of orofacial clefts with vitamin supplementation. Data from Shaw GM et al. Lancet. 1995 Aug 12. 346 (8972):393-6. Image by Christine Rathbun.